Royal Museums Greenwich (PW 3874)

Gillray cartoon lampooning Lady Hamilton as Dido in Despair when Nelson sailed for Copenhagen.

Much has been written about Admiral Lord Nelson’s famous signal as his two columns made their slow downwind approach towards the combined French and Spanish fleets off Cape Trafalgar on 21st October 1805. What doesn’t get discussed so often is the Admiral’s intended message. We can be fairly certain, not least from Lieutenant Pasco’s own recollections of his instructions, that Nelson had asked for the word ‘confides’ which was, with his agreement, substituted with ‘expects’; the former requiring to be spelled out while the latter was coded as a three-flag hoist in Popham’s Vocabulary Signalling Book. But was his intention to signal ‘England confides…’ or, as historian David Howarth suggests in his 1969 Trafalgar, The Nelson Touch1 the less jingoistic intimation ‘Nelson confides…’?

Royal Museums Greenwich (PW 3874)

Gillray cartoon lampooning Lady Hamilton as Dido in Despair when Nelson sailed for Copenhagen.

Despite the lampooning of Nelson and his relationship with Emma Hamilton in the press and popular prints, there is no doubting the mutual affection, respect and reciprocated confidence he inspired in the men under his command. There is only anecdotal evidence that he proposed the opening words ‘Nelson confides’ in a conversation with Captain Blackwood of the frigate Euryalus, who was still aboard Victory at the time. Whether he changed his mind or was persuaded otherwise we don’t know. But from the testimony of Nelson’s own words, writing to Admiral Lord Howe acknowledging both Howe’s congratulations on his success at the Battle of the Nile in August 1798 and the effective deployment of Howe’s new signal flags, he says ‘I had the happiness to command a Band of Brothers… each knew his duty’. 2 Surely it would be a similar sentiment of quiet confidence that he personally wished to express directly to his captains and men before the opening shots were fired at Trafalgar? The signal immortalised in heroic memory doesn’t quite do that.

How was the signal received? From a mix of anecdotal evidence and records from logbooks of ships in the fleet, it seems likely, despite the efforts of the repeating frigates deployed between the two columns, that it was seen by only a handful of ships. Responses varied from muttered oaths about duty to Vice Admiral Collingwood’s variously reported remark ‘I wish Nelson would stop signalling. We know well enough what to do.’3 Nevertheless, when the full signal was read to him, Collingwood, in the van of the leeward division, approved it warmly as did the ‘Tars of the Tyne’ as he liked to address his men aboard the Royal Sovereign. According to an account published in the Navy and Army Illustrated of 1896, they greeted the message with a ‘burst of cheering’.4

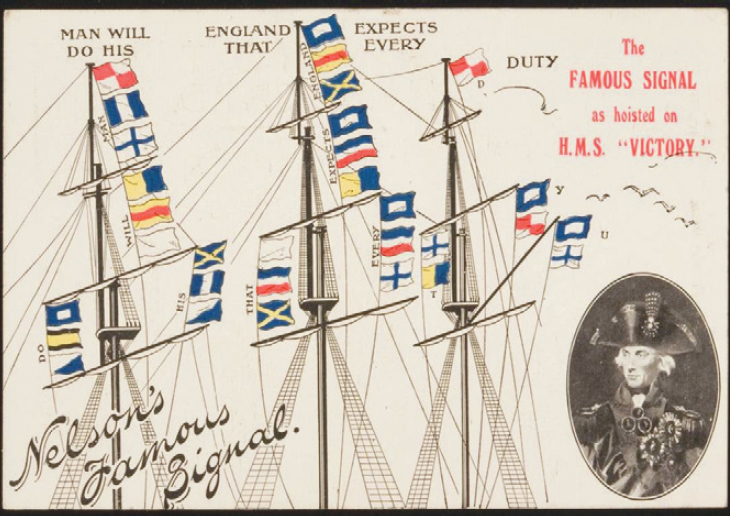

But whatever its immediate effect and irrespective of Nelson’s original intention, the death of the Admiral at the moment of victory soon endowed it with mythic status; often misquoted and frequently re-appropriated to this day. While documents of record give us some certainty over the words encoded: “England expects that every man will do his duty”, shown in the twelve hoists on these pages and above in an Australian postcard from WW1, versions omitting and adding words abound, with the opening words ‘England Expects’ frequently used as shorthand for the full signal. And, if there is confusion over the exact wording, there has, at least until the painstaking work undertaken by Lt Colonel W G Perrin in 1908, been equal confusion over the flags used to make the signal.

[PD-UK-Unknown]

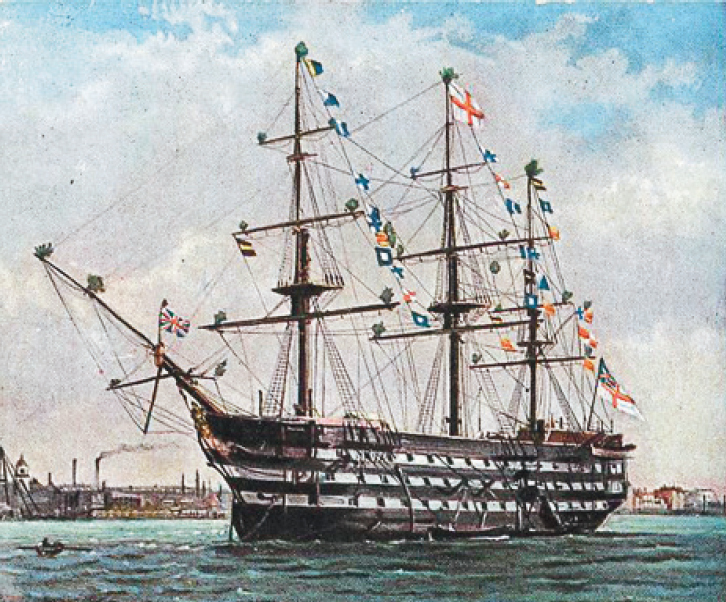

Souvenir postcard of HMS Victory published for the Trafalgar Centenary in 1905. The flag hoists are taken from the superceded 1799 code.

Perrin, upon whose scholarly 1922 study British Flags: Their Early History and Their Development at Sea much of the timeline of the previous section is based, was appointed Admiralty Librarian in 1908 during Admiral ‘Jackie’ Fisher’s first tenure as First Sea Lord. It was his research published in Nelson’s Signals: The Evolution of The Signal Flags (right) in the same year that revealed the errors in earlier depictions of the Trafalgar signal. These had been based on the assumption that the 1799 code was still in use in October 1805. In fact, as Perrin discovered, the code had been changed and manuscript amendments issued to the fleet after the capture of the 1799 code book in April 1803.

[PD-UK-Unknown]

The flag hoists on these pages depict Nelson’s signal made using Popham’s Marine Vocabulary of 1803. Each word is encoded numerically in a three-flag hoist with the exception of ‘duty’ which had to be spelled out. Each letter of the alphabet was represented by numerals 1 to 25, with ‘I’ and ‘J’ combined (9) and ‘V’ (20) and ‘U’ (21) reversed.

[Crown Copyright]

The signal, most likely hoisted in succession on the mizzen flag halyards to afford greatest visibility to ships astern, was quickly followed by Nelson’s signature call for ‘Close Action’ – signal 16 in Popham’s code. It remained aloft until shot away.

There can be few military signals that have embedded themselves so deeply into national popular culture or, in different conflicts, been reprised to express a similar sentiment – even in a single flag.

Tojo Shotaro (1865-1929)

Code flag ‘Z’ hoisted aboard Admiral Tōgō’s flagship before battle was joined at Tsushima. It still flies today on the Mikasa, now a museum ship (below).

Japanese Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, before engaging the Russian fleet at the Battle of Tsushima in May 1905, ordered the single hoist of International Code flag ‘Z’. By pre-arrangement this was to be interpreted as ‘The rise or fall of the Empire depends upon this battle; everyone will do his duty with utmost efforts’. Tōgō had trained in Britain, joining the Training Ship HMS Worcester on the River Thames at Greenithe in 1872. Gunnery training was carried out aboard HMS Victory at Portsmouth where, in his biography of the admiral, Jonathan Clements records the speed with which the young Tōgō worked out the hoists of Nelson’s Trafalgar signal flying from Victory’s masts.5 The signal made a lasting impression that he was to emulate with a single flag at Tsushima and flag Zulu still flies to this day from the upper yard of his flagship Mikasa, now a museum ship in Yokosuka.

© Imperial War Museum (Art. IWM PST 113454)

Had Popham’s code enabled Nelson’s originally intended intimacy of confidence rather then the mandatory ‘expectation’ signalled to the fleet, would the signal have had such a lasting impact?

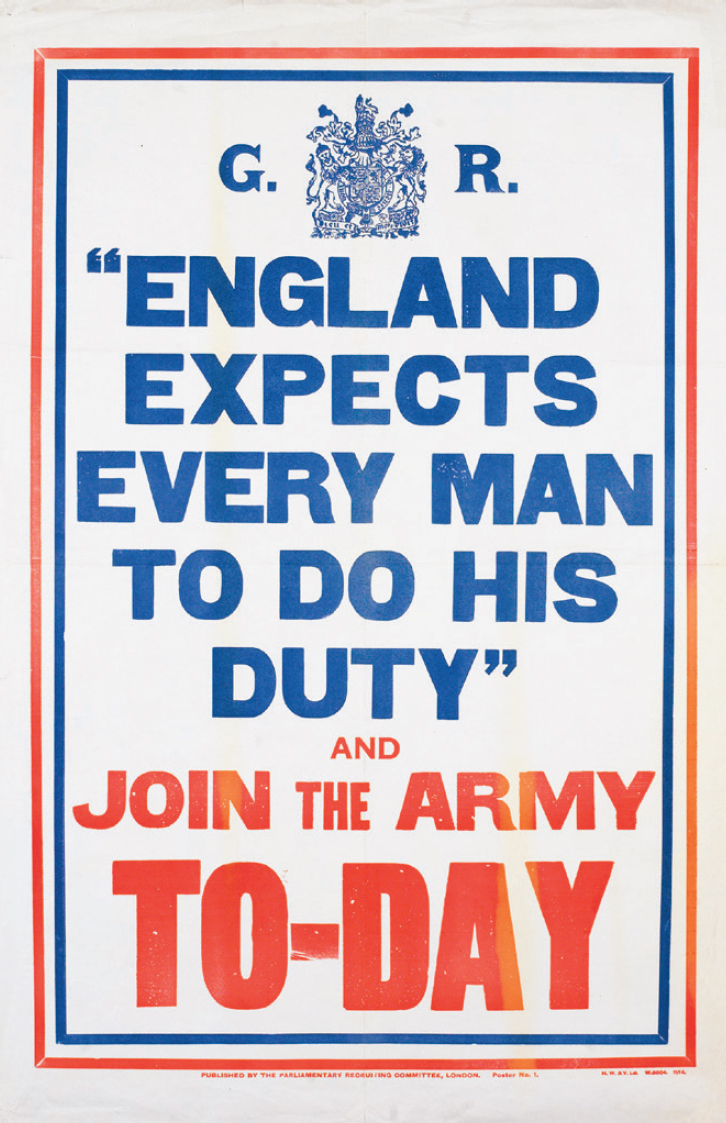

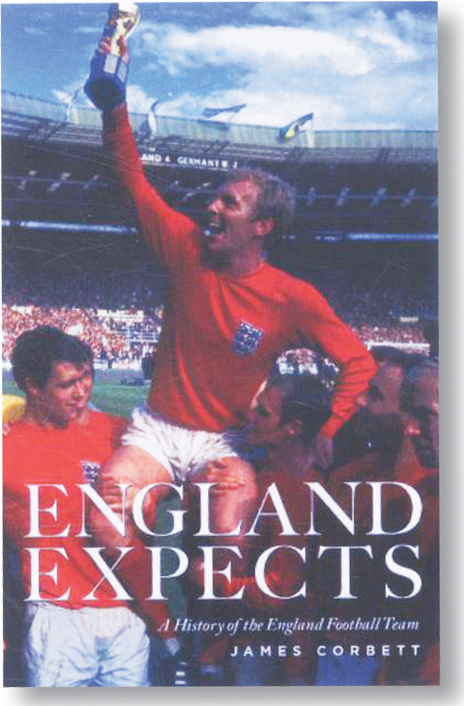

And if, as David Howarth has argued,6 the signal had been made with the personal appeal of Nelson rather than the substituted ‘England’, would it so readily have been pressed into service for everything from recruitment posters in both World Wars (above and right) to a history of the England football team? Or perhaps it would have been re-invented to meet the need.

De Couber tin Books

Harold Forster (1878-1918) National Archive INF3/163 [CC-BY]