The publication in 1857 of the first Commercial Code overlapped with later editions of the Marryat Code, with many mariners preferring the latter. HM ships on the East Indies station continued to use Marryat’s code to communicate with merchant ships and there is anecdotal evidence of the code still in use in the 1890s,1 by which time the original Commercial Code published by the British Board of Trade in 1857 was under review by the Washington International Maritime Conference of 1889. This resulted in a revised code now with a full alphabet published in 1897 and officially adopted in January 1902.

The code was again revised in 1931 and published as the International Code of Signals in seven languages with effect from January 1934. Rectangular flags were used for all 26 letters of the alphabet and numeral pennants introduced together with three triangular substitute flags and an answering pennant/code flag, shown here on the cover of the author’s 1961 edition of Brown’s Signalling2 that no cadet could be without. This is the code that is still in use today.

Norfolk Museums Service (Time and Tide Museum)

Though the International Code has been adotped throughout the world, we should not underestimate the impact that some of the earlier proposals had when first introduced. While the Royal Navy had settled on Popham’s Vocabulary Signalling Book in 1816, there was no universal equivalent for merchant shipping until the publication of Frederick Marryat’s Code of Signals for the Merchant Service. Published in 1817, it was the first of many competing proposals (see Timeline pages14 and 15) and one of two that deserve attention here.

The other is the Telegraphic Dictionary and Seaman’s Signal Book first developed by Henry J Rogers in Baltimore in 1845. This became his American Code of Signals which was adopted by both the Merchant Marine and the US Navy with an endorsement from the Secretary of the Navy J C Dobbin in April1855 urging Commanding Officers to ‘…embrace every opportunity to familiarise the Service with the use of these signals’.3

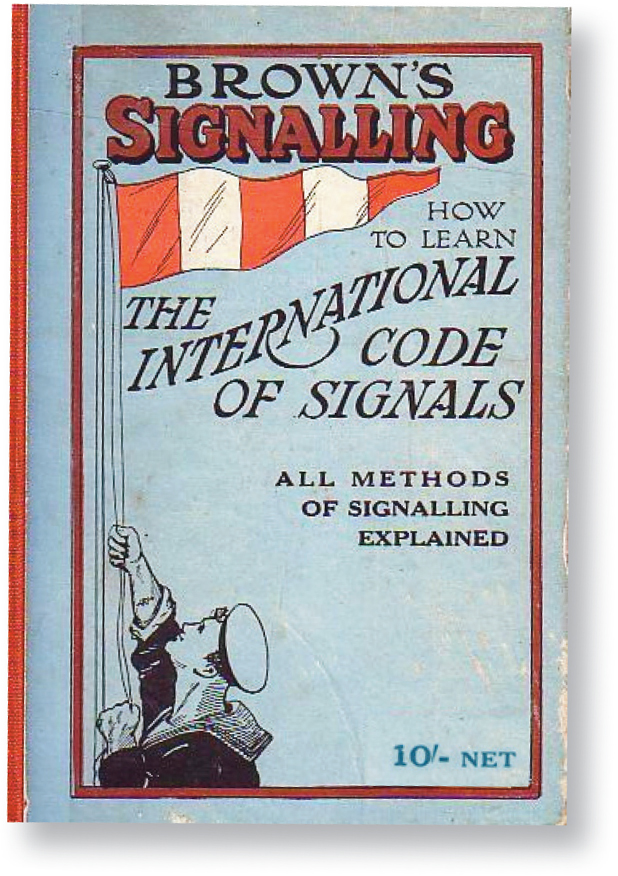

Both codes used numeral flags only with Marryat’s employing six additional flags to qualify the meaning, two examples of which are shown here: a ship’s identifying signal letters and a four-flag hoist preceded by the ‘Rendezvous’ flag to indicate a port or destination.

Marryat’s First Distinguishing Pennant followed by numerals 4072 of the British barque Frederica of Yarmouth (above) painted in 1865.

Four numerals preceded by the ‘Rendezvous’ flag indicates a geographical location, in this case Braye Harbour on Alderney.

A letter from a ship master to the Nautical Magazine in April 1840 testifies to the value of Marryat’s system, describing how he was warned of reefs and a safe course to steer in the Torres Strait by another ship. The letter goes on ‘…by means of Marryat’s Code of Signals any telegraphic communicatioin whatever may with facility be transmitted’.4 He ends by observing that if shipowners ‘…did properly appreciate the value of these signals, no ship would be without them’. It is fortunate that both ships in the exchange were equipped with a set of flags and Marryat’s code. Clearly not all were.

The six sections and 391 pages (Richardson edition, 1861) of Marryat’s code book list permutatioms of four-flag hoists; Rogers’s American Code used combinations of two, three, four and five numeral flag hoists and listed more than 60,000 closely printed individual signals. Subjects ranged from the purely practical: time signals, pilotage and navigational hazards, to intelligence on the price of stocks. Signal 247 shown left, for example, represents a one-sixteenth rise in cotton prices.5 Shown below is a more mundane exchange which echoes the title of this book.

Two hoists in Rogers’s code: ‘Where are you bound?’ with the answer ‘New York’.

Alfred Jensen, 1893

The Commercial Code published by the Board of Trade in 1857 broke with the all-numerical codes, using 18 alphabetic flags in permutations of two-, three- and four-flag hoists. With no vowels, there was little scope for spelling out words, but it was the beginning of a universal system that gradually replaced the Marryat code. A note on the title page of the 1873 supplement of British ship codes (some 18,700 vessels) expressly urges that ‘This Code is used on board HM ships and that Marryat’s code is no longer supplied to HM ships’.6 A later advertisement offers to provide the necessary flags to fully comply with the International Code for twelve shillings and warned that insurers would require it ‘…as a means of seaworthiness’.

WM SP 1310 [PD-UKGov]

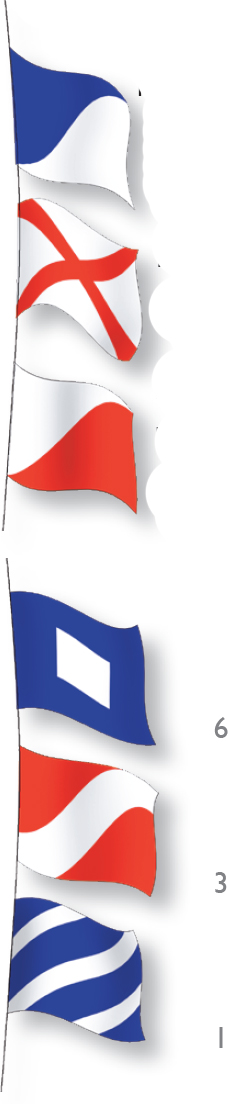

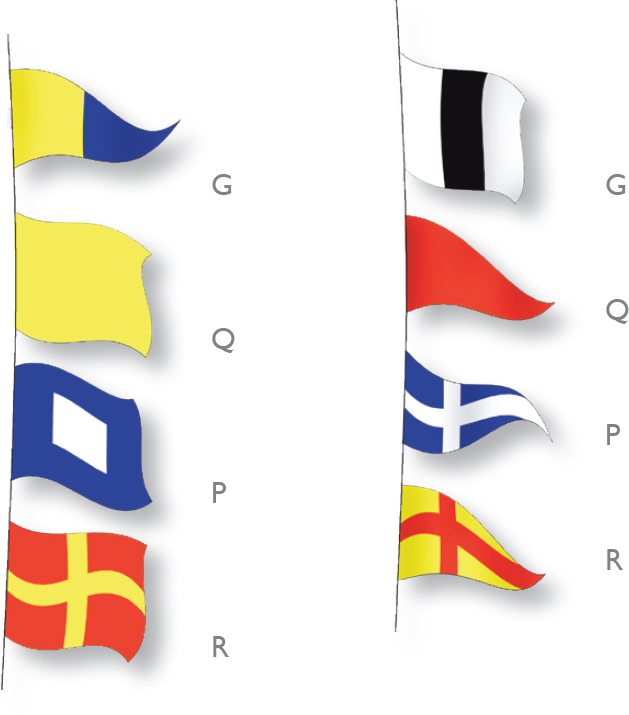

Four-flag hoistsbeginning with G were initially reserved for HM ships. Here the light cruiser HMS Caroline, now a museum ship in Belfast, is represented in the 1902 International Code, and the 1913 Naval Code.

The German barque Pisagua, painted in 1893, flies her signal letters in the International Code. Signal letters for German ships later changed to start with ‘D’, the initial ‘R’ reserved for Russia and, later, the Soviet Union.

International Code Groups (1934-1962)

The following message is spelled out alphabetically.

Two-flag hoists were reserved for urgent signals relating to navigation and safety at sea, and remain so to this day. The hoist shown here requests the depth of water on the bar.

Three-flag hoists AAA to ADV were reserved for compass bearings and time; ADW-AHB for a model verb and qualifying phrases; AHX onwards were allocated to the General Code. This hoist warns ‘I have had fog whilst passing through ice area’.

Three-flag hoist indicating a relative bearing. AAR is 30° to port.

Four-flag hoists beginning with ‘A’ denote a geographical location. AMTT is Port Said.