[PD-UK-Unknown]

North Atlantic convoy during World War II with hoist ZGJ above.

If the Battle of Jutland pushed flag signalling to the limit, it was by no means the end of visual signalling in the face of growing use of W/T. Signalling by flag, flashing light and semaphore remained and still remains the only secure method for fleet communication with ships in sight of one another.

[PD-UK-Unknown]

North Atlantic convoy during World War II with hoist ZGJ above.

US Naval Education and Training Command

Lessons had been learned from Jutland and other actions during the war and in particular from the introduction of the convoy system in 1917. With war looming again in 1935 the Admiralty issued a substantial Naval Appendix to the International Code of Signals which detailed signalling protocols between ships in convoy and their naval escorts. Every possible convoy manoeuvre was covered in three, four and five-flag hoists including the one signal that no merchant ship master wanted to see addressed to his ship: ZGJ (left)– ‘If you cannot maintain present speed of convoy you will have to proceed independently unescorted.’1

Two years later a revised Naval Code was issued (see page 37), designating seven flags: C, E, F, G, H, M and R from the 1934 International Code as special naval flags to meet changing needs – not least naval aviation, with flag ‘F’ still in use today to signal fixed-wing flying operations from an aircraft carrier.

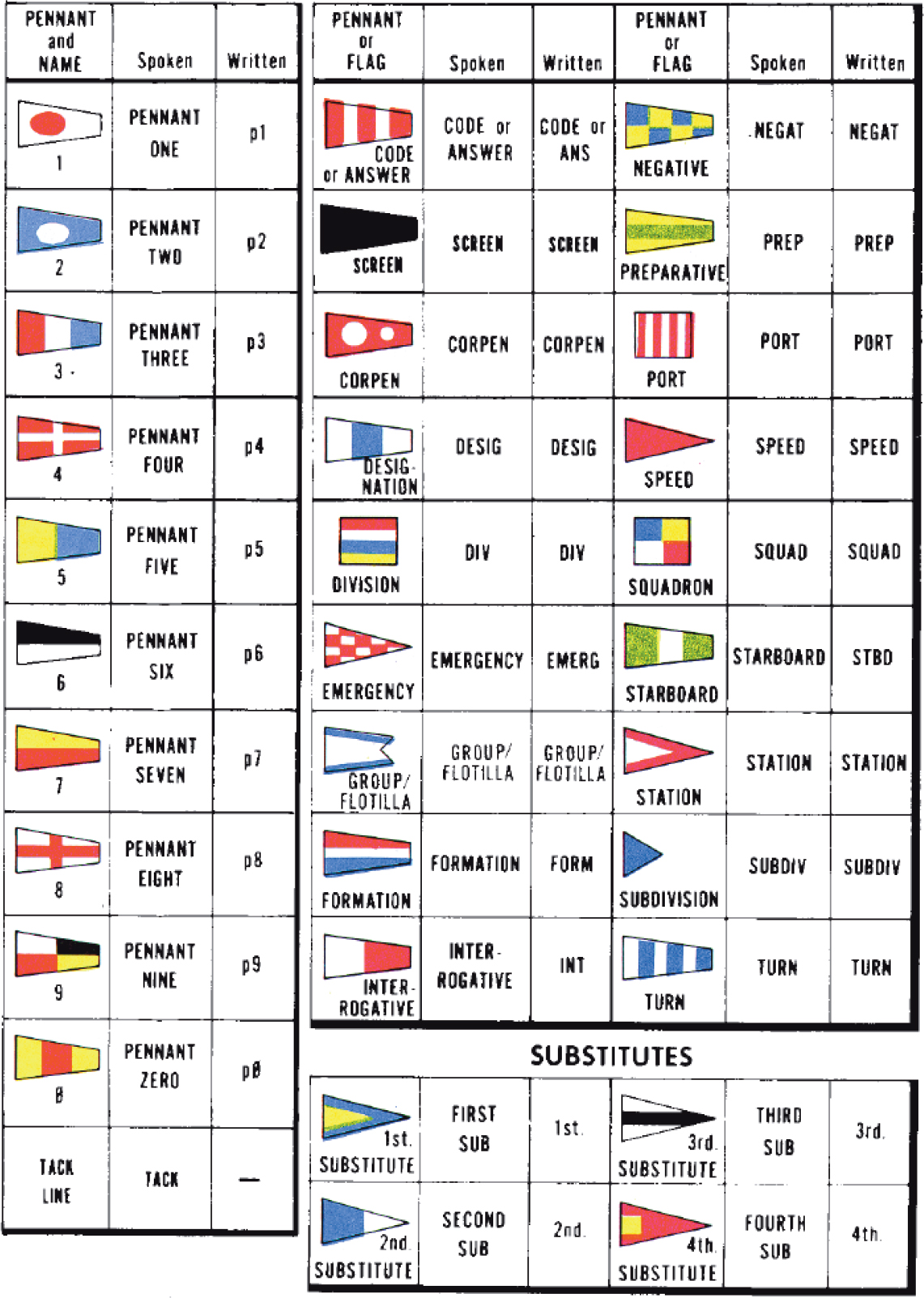

By 1944, the Naval Code had grown to incorporate numeral and special flags from the US Navy and would, alongside the International Code, become the basis of the Allied Maritime Tactical Signalling and Manoeuvering Book (known as ATP-01, Vol II) with the formation of NATO in 1949. Regular updates of ATP-01 are issued by the NATO Standardisation Office to the present day. The NATO ‘flag bag’ now contained 68 flags: 26 alphabet flags and 10 numeral pennants from the International Code, 10 numeral flags from the US Navy, four substitutes (three from the International Code plus a fourth from the USN) and 18 special flags, most of which had been introduced from the US for combined fleet signalling in 1944 with some changes of meaning. Shown left is the page of numeral pennants and special flags from a 1982 copy of the US Navy Signalman Training Manual.2

[PD-USGov-Mil-Navy NH 103681]

Although the Royal Navy had operated with US and Royal Canadian naval forces in the North Atlantic and with the Royal Australian and New Zealand Navies in the Mediterranean and the Pacific during World War II, the task of harmonising visual communications between the navies of the twelve founding members of the NATO alliance was formidable and urgent. The first major naval exercise undertaken by Allied Command Atlantic, codenamed ‘Mainbrace’, took place in September 1952 off Norway’s North Cape; 203 ships representing nine nations took part including 66 ships of the Royal Navy. Among them was Britain’s newest and last battleship, HMS Vanguard, seen in the Associated-British Pathé’s newsreel coverage of the exercise (reconstructed title still shown left).

Beside NATO’s standardisation of signalling procedures, the UK, the United States, Australia, New Zealand and Canada also share responsibility for allied communications through the Combined Communications-Electronics Board. ACP130 (A) Communications Instructions Signalling Procedures in the Visual Medium sets out a ‘concise and definite language’3 for visual communications in all mediums: flags, flashing light, semaphore, pyrtoechnics and panel signalling, the latter included in the NATO wall chart of 2018 below. Visual signalling is alive and well.

NATO

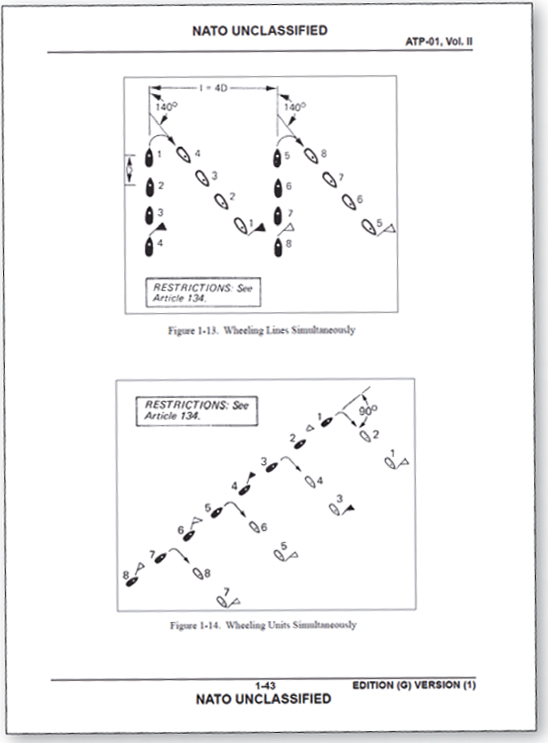

Page setting out squadron wheeling manoeuvres from ATP-01, Vol II; Bigot de Morogues (see p.11) would have approved.