Four-flag hoist followed by Naval Code E (International Code J) indicating ‘I am going to communicate with you by semaphore’. The signal letters (GQMJ in the 1915 Naval Code) are those of the Dartmouth training ship HMS Britannia.

The introduction of Sir Charles Pasley’s seagoing semaphore enjoyed some initial enthusiasm, perhaps in response to the frustration some had found in Rear Admiral Popham’s twin posts, about which Pasley had himself been particularly critical. Instructions for its use appeared unchanged through five revisions to the Vocabulary Signalling Book but from Commander Mead’s 1935 account,1 there appeared to be no consensus as to what it was for: communication with fixed stations ashore, station keeping, manoeuvring signals or ship-to-ship messages spelled out in plain language?

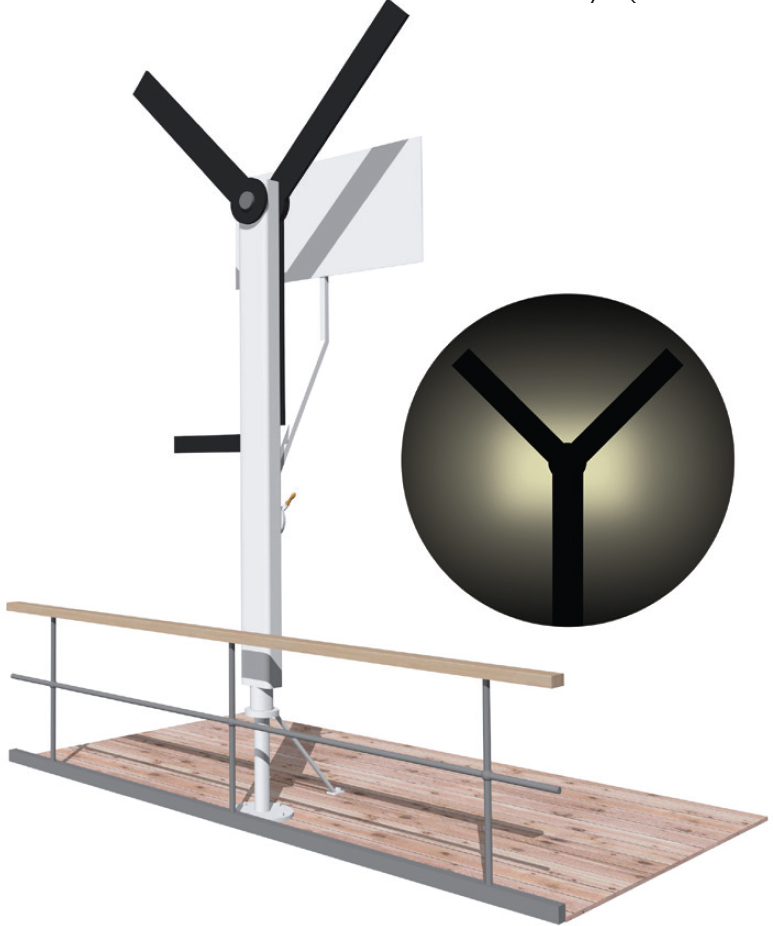

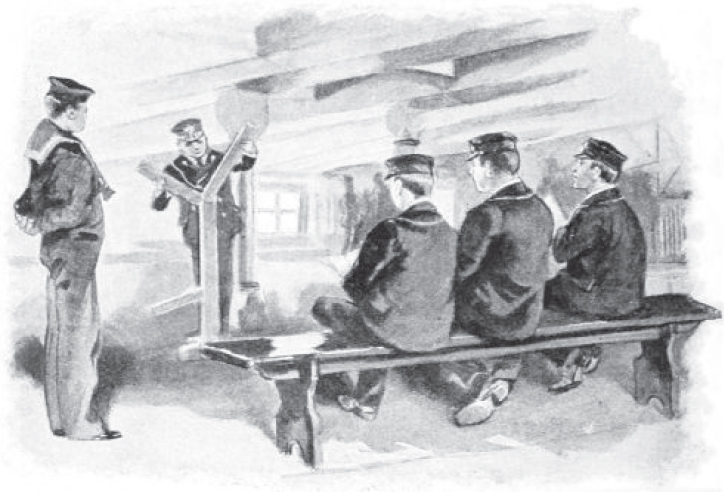

A full half-century after its introduction, the Admiralty invited opinion on the most suitable sizes for the semaphores which were only then beginning to gain wider support. Two sizes were chosen and issued from the dockyards in June 1876: a 15ft (4.6m) mechanically operated version and a much smaller portable version with the arms worked by hand as in the instruction to cadets aboard HMS Britannia at the turn of the century (above right). In 1888 some liberties were taken with Pasley’s design and a third arm added to extend the number of governing signs when used for signalling manoeuvres, together with a reflective illuminated panel at the rear of the machine to enable night working. It was a short-lived experiment; by 1897, three-arm machines along with their electric light were declared obsolete and semaphore no longer used for manoeuvring. With the Admiralty carrying out simultaneous experimentation in Morse code and coloured light signalling, covered in the following section, it seems in retrospect a bizarre path to have followed, when semaphore had already proved its worth in daylight ashore and afloat.

Four-flag hoist followed by Naval Code E (International Code J) indicating ‘I am going to communicate with you by semaphore’. The signal letters (GQMJ in the 1915 Naval Code) are those of the Dartmouth training ship HMS Britannia.

Virtual model of how the three-arm version of Pasley’s semaphore with its reflective light panel might have looked, with night view (inset right). (Source: Sketch after Illustrated London News in Mead Part V, p.38)

The Story of Britannia, London, Cassel and Co, 1904

[PD-UKGov]

HMS Nile c.1892 showing two semaphores on her foremast.

[PD-UKGov]

Sir George Tryon’s flagship HMS Victoria in dry-dock in Malta, 1892. Note the bridge wing semaphores.

From 1898 new ships were being fitted with a standard two-arm mechanical semaphore on a 15ft (4.6m) column. These were normally fitted on both bridge wings (see HMS Victoria above), though sometimes mounted at the aft conning position, and could be trained to continually face the receiving station. The indicator arm was gradually phased out and this type of semaphore was still in service during the Second World War.

Despite experiments with mast mounted semaphores as early as 1822, it would be another sixty-five years before further trials were carried out with two pairs of semaphore arms fitted to the mizzen masts of two elderly armoured frigates Minotaur and Agincourt. Within a further two years, three-arm semaphores were fitted to battleships and some others, either on existing masts as with HMS Nile (see left), or on specially fitted signalling masts. These arms, two pairs of which were fitted, one facing fore and aft and the other athwartships, were operated by chains and sprockets within the mast and with minimal counterbalance on the 6ft (1.8m) arms must have been a considerable challenge for the signalmen. With three arms, each with a cross piece near the end to distinguish it from the mast in the upright (4) position, these semaphores were primarily used for manoeuvring signals in daylight, though two arms could be used for alphabetic messages. Mead suggests that the move towards mast-mounted semaphores with enclosed mechanisms was made in anticipation of war and the need to replace flag signalling with something more robust.2

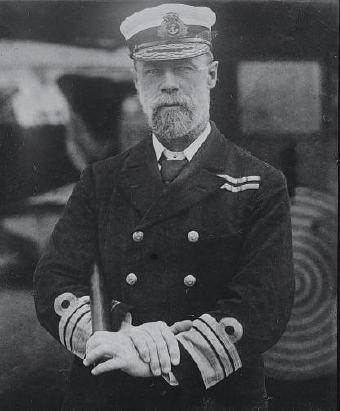

Whether or not encouraged by the three-arm experiments, it was not until 1895 that the first truck-mounted semaphores were fitted. Often acknowledged as the invention of Sir Arthur Wilson, at that time a Rear Admiral in command of the experimental torpedo squadron, this two-arm semaphore comprised steel arms 12ft (3.6m) long by 15in (.38m), again operated by an even longer system of chains and pulleys within the mast which resulted in what was descibed as a ‘considerable backlash’ between the operating levers and the semaphore arms. Given the step between the lower mast and the topmast on HMS Minerva (see below) this is not hard to imagine, nor is the physical effort required which, in harbour, was exercised daily between 0715 and 0745.

Australian War Memorial (001069/04)

Signalmen aboard HMAS Akuna using two-arm mechanical semaphore c. February 1940.

[PD-UKGov]

Vice Admiral, later Admiral of the Fleet, Sir Arthur Wilson. In 1897, he succeeded Sir John ‘Jackie’ Fisher as Third Naval Lord and Controller of the Navy.

[PD-UK-Unknown]

The protected cruiser HMS Minerva exercising her masthead semaphore in harbour while serving with the Channel Squadron in 1899. She is making the signal ‘N’ (46) used by scouting cruisers to address units closer to the battle fleet.

With rapid developments in wireless telegraphy from 1902 onwards, the days of the masthead semaphore for long-distance signalling were numbered and within a decade they were phased out completely, leaving the more manageable bridge-wing semaphores. But they were not always available or could not be brought to bear, so signalmen improvised either with their arms or hand-held flags. From the mid-1880s these could be variety of coloured patterns before International Code flag ‘O’, introduced in the 1901 code, was adopted as the most suitable for signalling against any background. For the first time in a hundred years, arms were again doing what machines had been contrived to imitate and they continue to do so to the present day.

Britannia Museum Trust, Royal Naval College, Dartmouth

Hand semaphore exercise aboard Training Ship HMS Britannia, c. 1903, from a set of postcards published by Gale and Polden.

Google Books

Cover of US Navy Signal Manual, 1982.

One of fifty cigarette cards in Wills’s ‘Signalling’ series, 1911.