US Naval Historical Center [PD-US]

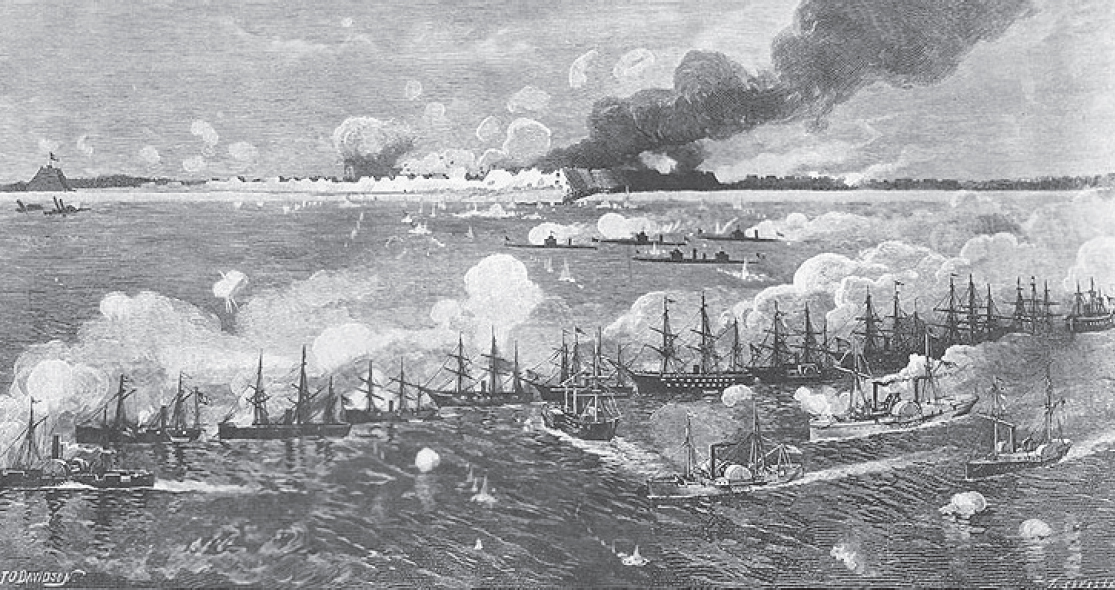

Rear Admiral David D Porter’s squadron bombarding Fort Fisher, 13th to 15th January 1865. He later wrote to Coston praising the success of her night signals.

When Rear Admiral David D Porter manoeuvred his ships off the Confederate-held Fort Fisher in the early hours of 13th January 1865, the night signals he relied on where those developed by a remarkable woman, Martha J Coston.

US Naval Historical Center [PD-US]

Rear Admiral David D Porter’s squadron bombarding Fort Fisher, 13th to 15th January 1865. He later wrote to Coston praising the success of her night signals.

By the outbreak of the American Civil War in April 1861, flag signalling in the US Navy was well established and, with the addition of Myer’s ‘Wig-Wag’ system, coded visual communications by daylight were routine. By night, however, before the development of reliable shutter systems for signalling by electric light, the centuries-old practice of lantern signalling by permutations of colour, position and number was challenging in all but the calmest conditions. With the transition from sail to steam, the corresponding increase in speed and the precision needed in manoeuvring fleets unfettered by contrary winds, the need for a swift and reliable means of night signalling became paramount. It was the pursuit of this to which Martha Coston would devote much of her life.

Born Martha J Hunt in Baltimore in 1829, Martha moved with her family to Philadelphia where at the age of 16 she met and fell in love with a young Boston scientist, Benjamin F Coston, who was in charge of the Naval Pyrotechnics Laboratory at Washington Navy Yard. Sources differ on the date of her marriage to Benjamin, but by the time he died in November 1848, probably from excessive exposure to toxic gasses inhaled during his work, his widow, still only 21, had four children to care for. Tragically, two of them died along with her mother within two years.

Martha Coston from a full length portrait c.1880. Artist and exact date unknown.

In straightened circumstances and, by her own admission in her autobiography1 ‘her own ignorance and the duplicity of others’, she began a search of her husband’s papers, amongst which were proposals for pyrotechnic night signals. Discovering that some prototypes had been made and left in the care of a naval officer, Coston eventually secured their return and persuaded the Secretary of the Navy Isaac Toucey to have them tested. The tests were not a success, but, with encouragement from Toucey who could see ‘that the invention… would be of incalculable service to the Government’2 she set about trying to realise the potential of her late husband’s invention. Without any knowledge of chemistry or of business practice, she was totally reliant on the practical assistance and guidance of others – all, of course, male.

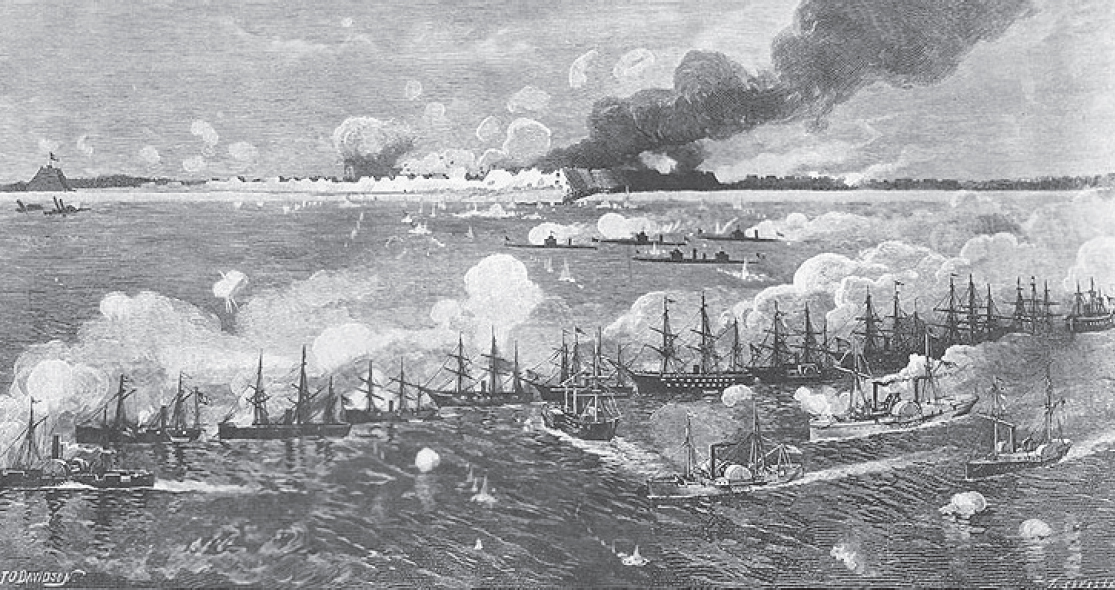

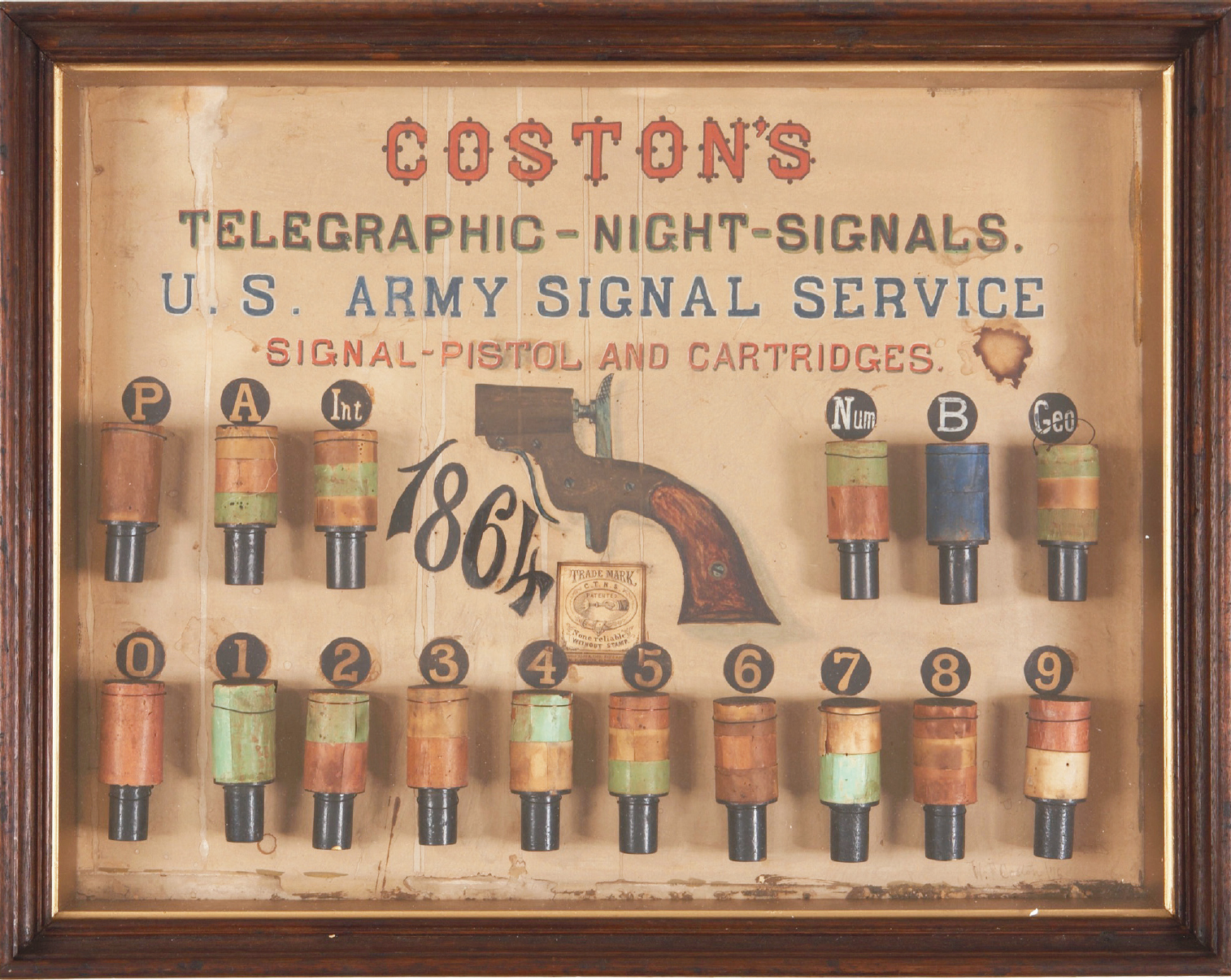

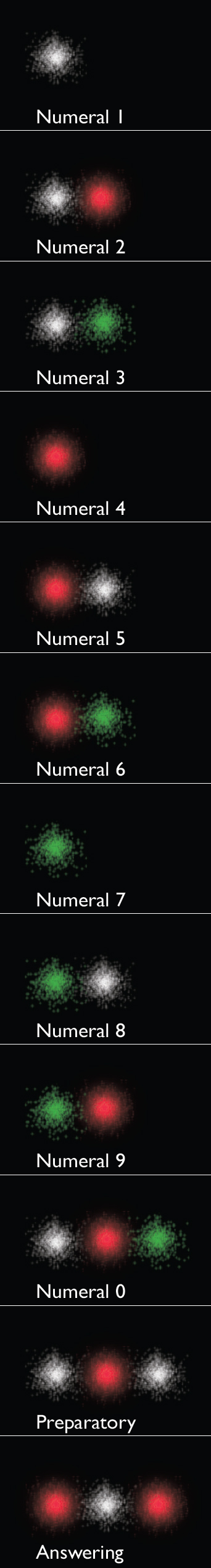

In time she had perfected a ‘pure white and a vivid red light’; she still needed a third colour, preferably a patriotic blue, to enable Benjamin’s proposed three-colour signal code to work. The turning point came while watching the New York firework celebrations marking the completion of the transatlantic cable in 1858. Posing as a man for fear that her requests would not be taken seriously, she wrote to several of the pyrotechnic manufacturers who had given the display to try and find the blue she was after, or failing that, a ‘brilliant green’. Within ten days she had received a reply with a sample of a green compound that proved successful and wasted no time in establishing a partnership with the New York firm of G A Lilliendahl, later to become the Coston Signal Company, to manufacture the composite cartridges. Twelve of these in different colour combinations, together with a hand-held device from which they could be safely fired were the essential components of the Coston Telegraphic Night Signal System.

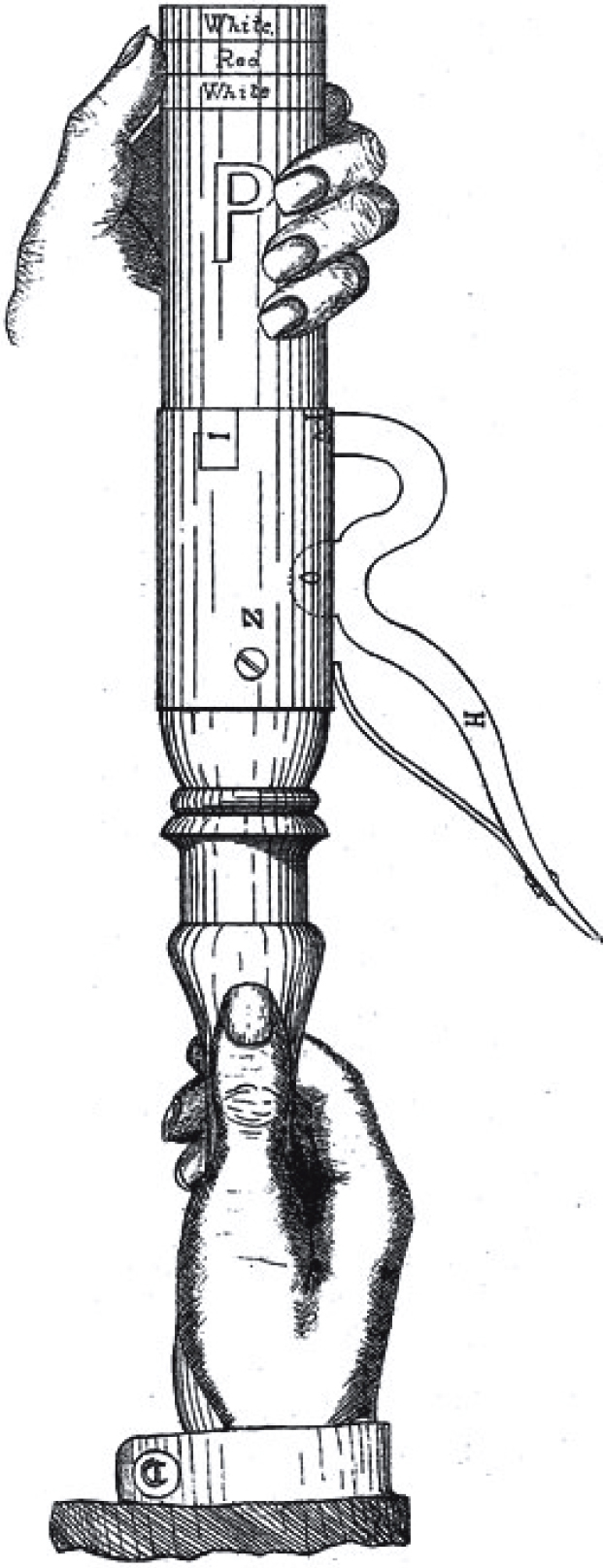

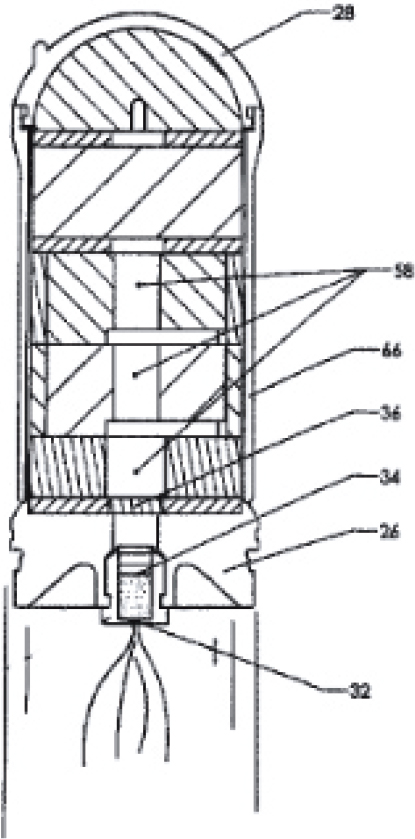

Under the direction of Secretary Toucey, a Navy examination board rigorously tested the signals in all their different permutations and endorsed them as ‘decidedly superior’. They had passed the test and orders for multiple sets of flares immediately followed, though the Navy hesitated to buy the patent outright, which became the subject of protracted debates in Congress. On 5th April 1859, Martha Coston was granted a patent which, probably for sound business reasons, given her husband’s established reputation as an inventor at the Navy Yard, she registered in her husband’s name.3 Subsequent refinements, the first in 1871 (detail left), were registered in her own name and further developments of the Coston signal system were registered by her two surviving sons Henry H and William F Coston in 1877 and 1901.4

Signal Corps Association [www.civilwarsignals.org]

A display case of Coston’s Telegraphic Night Signals and Signal Pistol adapted for use by the US Army. The cartridges were fitted into the pistol and fired with a percussion cap and remained in place until the colour combinations had burned through before inserting the next flare. The set normally comprised ten numeral flares, a preparatory signal and an answering signal; this set has four additional signal flares. Though dated 1864, the display is signed at bottom right by Martha’s son ‘W F Coston, [18]76’

With Congress prevaricating over the purchase of her patent, Martha, having secured patents on her invention in several European countries, set off for Europe where she stayed for two years negotiating the sale of patents to the British and French governments, the latter successfully. By the time she returned home in June 1861, the Civil War was two months old and she re-opened her petition to Congress for the sale of her patent which, she argued, would prove ‘a valuable auxiliary for the Navy’. By August a bill authorising the purchase was passed; the begrudging price of $20,000 (approximately $500,000 in 2018)5 was exactly half what she had asked for. By then her company had already supplied flares to 600 ships of the Union Navy.

Sequence of colours representing each numeral in the Coston Code of 1859-1864. Each colour lasted approximately 8 secs.

Fort Fisher fell on 15th January 1865, closing off the Confederates’ last access to the sea at Wilmington. Admiral Porter was later to write to Martha Coston singing the praises of what must by then be regarded as her signals and the crucial role they had played in the deployment of his fleet. Praise for the Coston signals also came from commanders of blockading fleets off Louisiana, along the Mississippi and the Atlantic seaboard.6 But the greatest testimony to Martha’s dogged determination to build on her husband’s work is revealed in the latest iteration of the Coston flare – a tricolour signal projectile adapted for use in a standard US Army grenade launcher (below) – for which a patent was registered in March 2014.7

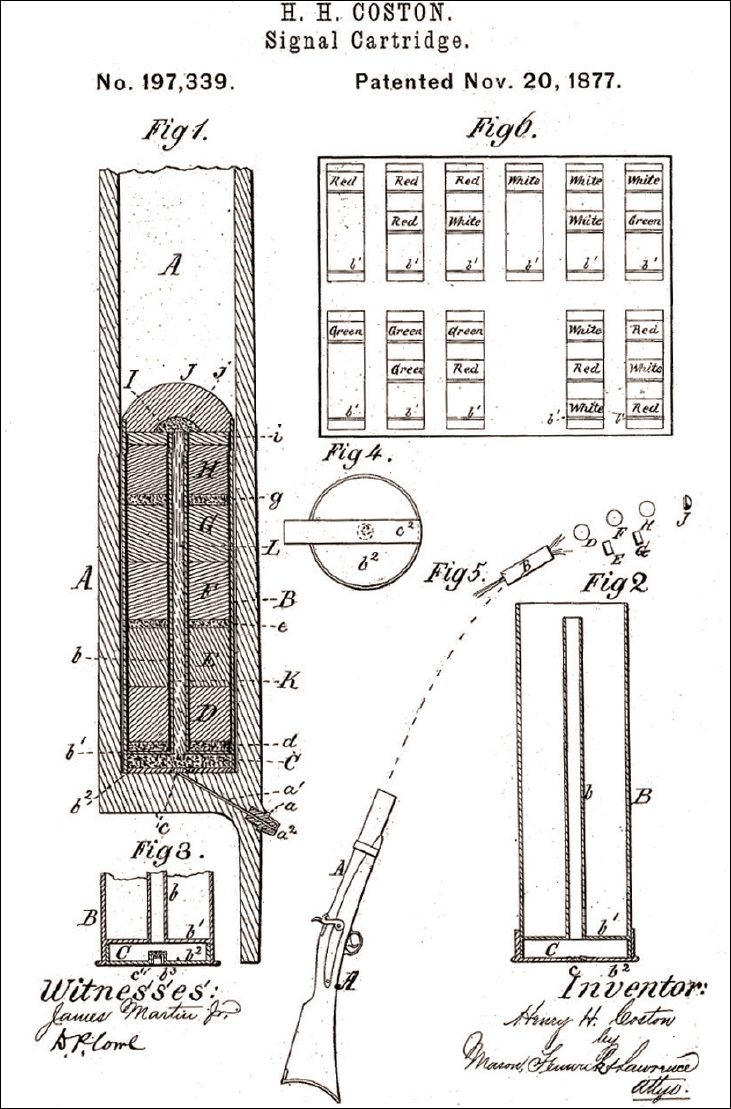

Since the patent granted to her eldest surviving son Henry in 1877 (above right) there have been no fewer than twenty nine applications for patents of variations on her acknowledged pioeering work.

US Patent Office

Diagram accompanying Henry Coston’s patent application of November 1877, for a Coston flare to be fired from a gun, releasing its coloured lights in the correct sequence at a given height. This, the specification rightly claims, ‘possesses great advantage over the stationary signals because the point signalled from cannot be discovered by the enemy.’ It is no surprise that this proposal was quickly taken up by the United States Life Saving Service that later became the US Coastguard Service.

1913 press advertisement for Coston’s Marine Signals, the opening line of which asserts ‘The only signal recognised by the British Board of Trade…’.