FOUR

The Maelstrom: To Auschwitz and Beyond

Der Tod ist ein Meister aus Deutschland…

PAUL CELAN

On Monday, July 3, 1944, a train left Kaposvar, Hungary, for Auschwitz, Poland, via Budapest. It was filled with Jews from the rural regions of southwestern Hungary, Polish Jews who had fled their native country in 1939 in advance of the German invasion to seek refuge in Hungary, and Jews who had converted to Christianity. Marked with a sign that read “Suitable for twelve cattle,” each wagon of the freight train was crammed with forty to fifty people, men and women, boys and girls, of varying states of health, wealth, and social status. The heavy sliding doors were tightly locked and entwined with barbed wire. The outside world was visible to the human cargo through narrow slatted openings originally designed to provide enough air circulation to keep cattle alive for the slaughterhouses of Europe. There was no way for the imprisoned passengers to open up the wagons from the inside for ventilation, for relief of bodily functions, or for physical mobility. Escape was impossible. Pressed into one of these freight cars were Bernie, his father, Louis, his mother, Bertha, and his younger brother, Alexander.

Before their departure, the Rosners and the other Jewish families of Tab had spent an entire week in an open field in Kaposvar. The food doled out was so horrible that most ate only what they had carried with them from their homes. Each family spread out the blankets and clothing they had brought in an attempt to mark off their own little plot of ground and preserve, at least symbolically, a sense of privacy. A woman screamed intermittently in desperation. A doctor who had brought medicines along attempted suicide. Bernie's mother tried to distract her young sons to shield them from their surroundings. But Bernie saw and remembered. This was the only time he thought seriously about escape. He told no one, not even his family, that he studied the positions of the German and Hungarian guards around the campsite to find an escape route —in vain. Once on the train to Auschwitz, all possibility of flight vanished along with the last vestiges of private space.

Bernie's solitary plan to flee raises the frequently asked question of why there was no widespread effort to escape, no general resistance. For both of us, the answer seems simple, quite beyond the overwhelming physical force that controlled these Jewish captives and the psychological cliché of their collective denial of the fate to come. Voting with your feet may be an American cultural heritage, but it was not a ready-made response for most European villagers faced with danger during this epoch. Where would they have gone? How would they have gotten there? Who would have received them? The immensity of the genocide into which they were about to be drawn was also beyond human imagination, and therefore beyond denial. Only the bestial and prescient could have had an inkling of the crematoriums that lay ahead.

July 3 started off hot. But rain fell in the afternoon, cooling down the stifling wagons and preventing the occupants from suffocating before their arrival four days and 400 kilometers later at the Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. There was little food or water, minimal space to move one's limbs, and only a couple of buckets to serve as toilets. While the train was temporarily stopped at Budapest, a woman handed an orange to Bernie through the barbed wire, saying it was from “someone who cared.” Bernie remembers that his father spoke little on the train and that his mother prayed a great deal and made sure that he and his brother had something to eat. Alexander developed a slight fever but claimed that he felt all right. When someone encroached on the family's small space on the floor of the cattle car, Bertha Rosner protected it. Time passed. Shortly before their arrival at Auschwitz, as they watched the passing countryside through the air slots crisscrossed by barbed wire, Bernie remembers that his father turned to him and said matter-of-factly, “It's all over.”

Like so many others, Bernie's train arrived through the turret-topped gatehouse and stopped at the unloading platform inside the Birkenau section of the camp. That notorious entrance gate and platform are still vivid in Bernie's memory, as are the two lifeless bodies of acquaintances who were left in their freight car after the living exited. Several in his wagon had lost their sanity during the journey to Poland. One was a young woman, Martha Banoczy, known in the Rosners' native village for her beauty, who pranced around the platform babbling incoherently, clad only in a short fur coat that failed to cover her pubic hair. Her family, assimilated into Hungarian society, had converted from Judaism to Christianity long before these events. After all these years, Bernie's voice bears a trace of sadness for this beautiful young woman and the catastrophic transformation she underwent during their common journey, displayed for the eyes and ears of the other villagers as well as the SS guards.

Decades later, Bernie still hid the terrible images and details of these memories in the recesses of his mind, only to look at them through the blurred vision of one who tried to think that they had happened in some other life—the stench in the air, the terrified milling crowd, the faces of his uncle Willy and his cousin Jeno, familiar names shouted in despair and hope, the disappearance of his father, the admonition of his mother before she too disappeared, taken away by the murderous arms of death on a gray day in July.

What about the others in the cattle cars? And not just on the Rosners' train but on 170 trainloads over three months in all that brought some 475,000 Jews to Auschwitz from Hungary alone? An enormous mass of humanity—475,000 individual lives—yet only a fraction of the numbers ultimately devoured in the Holocaust. Most of them perished, with their lives not lived out and their stories never told. How did the old people manage to move their stiff limbs to climb off the cars? Was Bernie's learned grandfather somewhere among them? Did some of them collapse when they reached the open air? How did their eyes adjust to the sudden brightness? Was the height of the platform level with the interior floor of the cattle cars? Why did some people go mad while others did not? Is “madness” really the right term to describe their state? Could there have been a “normal” reaction to this four-day transit to hell?

Bernie continues his recollection with the utmost precision. As he and the others waited on the platform, everyone was aware, victims and Germans alike, of a major Allied air strike in progress at the nearby industrial plants that were part of the Auschwitz complex. But this event did not alter the daily routine. Above the noise of the distant attack, orders were barked in German: “Ruhe, schweig' still, Schweinehund.” A rifle butt struck the head and back of a urinating man, and a boot knocked in the teeth of an inmate to whom a guard had taken a spontaneous dislike. Yet, at this point in the disembarkation, the violence remained primarily verbal. Too much individually directed brutality would have constituted an inefficient waste of time and energy; the agenda was, after all, mass extermination. Processing human beings through this destruction machine was itself the ultimate manifestation of violence. The Rosner family had arrived in the eye of the maelstrom that was devouring the Jews of Europe and other Nazi victims.

As the “leader” of their cattle car, and without time for goodbyes, Bernie's father was the first of his family to disappear from his life. I presume that by removing the potential leaders first, the Nazis could more easily manipulate the remaining victims for efficient extermination or assignment to holding barracks or slave labor.

Men and women were then ordered to separate, ostensibly for showers and delousing. Bernie's mother wanted her sons to stay with her. Some very young children were allowed to remain with their mothers. But twelve-year-old Bernie didn't want to shower with the women. His mother admonished him to stay with his little brother. Everything happened with breathless speed. Bernie saw panic in his mother's face as they were separated from her. Now he and Alexander were among the men; and Bertha Rosner disappeared forever.

Without their parents now, the Rosner brothers were moved along the paved part of the disembarkation ramp in a line of males. At the head of the line stood two SS officers dressed in their military uniforms who divided the column approaching them, sending some to the right and others to the left. They didn't know it at the time, but those moved to the left were earmarked for immediate extermination, the others for slave labor or later extermination. Bernie's brother, in front of him in the column, was moved to the left—he was ten years old and, in the minds of the SS guards, clearly not considered worth keeping alive. Bernie, remembering his mother's admonition, tried to follow his younger brother. For an instant, the SS officers watched passively, but after Bernie had taken two steps in his brother's direction, one of the SS selectors took him by the scruff of his neck and shoved him the other way. In this first cut, the Nazis apparently considered Bernie, who was two years older, a candidate for slave labor. He could always be eliminated later. As it turned out, this was the last time Bernie saw his brother. As Bernie was herded in a different direction, he didn't realize that his entire family was now gone.

His column slowly made its way past an enclosure that he later learned contained the gas chambers. He noticed how guards forced some stragglers inside the entrance and closed the heavy wooden barrier behind them. Bernie recognized an old woman from Tab in this group and heard loud noises and screams coming from inside after the barrier had closed. At that point he had no explanation for these terrible cries, and his group simply moved on. Bernie's group was marched past these barriers to a brick building where they were shaved of all body hair, deloused, and given showers. Bernie was then given clothing, including a jacket with a characteristic piece of striped cloth on the back that marked him as a concentration camp inmate. The yellow stripe painted across the front designated him as a Jew.

Bernat Rosner, twelve and a half years old, the sole survivor of his family, shorn of his hair, showered, deloused, and clothed in a concentration camp uniform, started his days in Auschwitz. He was assigned to barracks 34, Lager (camp) E, Birkenau, which was also called the Ziegeunerlager, because it was used in the early summer of 1944 as a “quarantine” camp for gypsies. Within a few weeks of Bernie's arrival, the remaining gypsies were removed from the site, gassed, and cremated. Once, as a truckload of gypsies passed by his barracks, Bernie remembers a particular gypsy who caught his eye and drew his flattened hand across his neck, indicating that he expected to be killed. Bernie began to get used to the constant acrid smoke that rose out of the chimneys of the crematorium—located less than a kilometer from Lager E—blowing the ever-present odor of death through the camp.

Each barracks had a chief Kapo and several subordinate Kapos, inmates charged by the SS to maintain order. Some of these Kapos were Jewish. They had the power to further brutalize inmates or to alleviate their misery to a small degree. Each prisoner was to receive a quarter loaf of bread per day. In reality, the Kapos in charge of Bernie's barracks first cut a piece for themselves out of the middle of each whole loaf, thus reducing the size of the remaining four portions given to the prisoners. One particularly cruel Kapo beat two boys to death. He had been a pediatrician.

Random beatings were one of the pastimes of many of these barracks leaders. More formalized punishments involved lashes administered with a rubber cable that had a metal wire inside it for added bite. Bernie once was given five lashes for being the last one out of the barracks. The SS in charge of the camp did not administer the beatings personally. Indeed, Bernie recalls, the SS preferred to delegate this dirty work and rarely attended the public floggings.

Each morning began when the Kapos banged on the wooden pallets, covered with thin, smelly straw matting on which six to eight inmates had spent the night. The inmates were ordered to line up outside to be counted. Bernie said that usually everyone got up, because those who did not were sent to the “hospital” from which they did not return. One inmate pleaded with increasing desperation about his need for insulin. The others convinced him that if he reported his illness he would be taken away and killed. As the diabetic grew weaker, fellow inmates continued to carry him outside for the daily roll call and to prop him up for the head count. Soon, however, he went into shock and died. For a few days after his death, inmates let the body lie among them, reluctant to give up even their own dead to the guards.

We know from documentary photographs that over the main gate of Auschwitz the Nazis had affixed the slogan “Arbeit macht frei” (Work Makes You Free). In Bernie's barracks, stenciled on a rafter and adorned with colorful, kitschy flowers, inmates could read the first line of a popular German folk song: “Es geht alles vorüber” (Everything passes). This sentimental song, one of many I learned in my youth, is still sung today in German taverns when the mood is jovial. It promises that after every December, a May will surely follow. The song is usually sung toward the end of an evening of drinking, right before “In München steht ein Hofbräuhaus,” when people link arms and sway back and forth in a heightened sense of solidarity. That macabre bit of interior decorating in Bernie's barracks faded at nightfall, as darkness settled in on their cramped quarters, and quite another song emerged, one composed by an inmate in Yiddish. Someone would start to sing it, then a second voice would join in. Soon most of the inmates would be singing. A few remained silent on their pallets, as Bernie recalls, to listen to its desperate cry for deliverance:

Eykho vi azoy und far vos

ogstu undz azoi?

i iz, foter, dayn rakhmones?

Habet Mishomaim Vreh

Fun himl gib a blik

Tsu di Yidishe kinder gib a glik

Lesh oys dem fayer un zol es

shoyn zayn genik.

Oh, why and for what

are you hunting us so?

Where is, Father, your mercy?

…

From heaven give a glance

To the Jewish children give a chance

Extinguish the fire—and

let it be enough.

The first word of this plaint, “Eykho” (how), hauntingly evokes the cry of grief that begins the Old Testament Book of Lamentations (“How lonely sits the city that was full of people!”). And the ending echoes the medieval night watchman's song that exhorted Germans to extinguish lamps and fires to prevent conflagrations from engulfing their towns. In the concentration camp, the ears of the guards keeping watch outside the barracks were closed; the plaint did not reach them. And the God the inmates invoked was deaf.

For a while Bernie nourished his own kind of hope. During his first weeks at Auschwitz, he wrote notes to his mother on scraps of paper and passed them on to inmates who had been selected for the day to work details in other parts of the camp. He never received a reply. As time went on, he simply stopped writing, even though he was still unwilling to accept that his mother was dead.

At one end of the encampment that faced the railroad platform, Bernie would watch the trains arriving with new inmates. The arrivals had become more and more frequent, because, as he recalls, the Germans were evacuating the ghetto in Lodz at the time. When no train was stopped on the tracks, he could see, at a distance of almost a kilometer, a camp filled with women and children. Although this camp was too far away to recognize or to shout to anyone, the sight gave him hope for a while that his mother and his brother might be among them. When inmates would occasionally discuss their chances of survival, Bernie brought up this distant sight of women and children to bolster the dwindling group who clung to hope in spite of the omnipresence of death. Feeding this hope was a semblance of normalcy that camp authorities encouraged in order to maintain tranquillity and thus facilitate the smooth functioning of the death machine.

The SS provided musical instruments to inmates who could play them, and camp concerts took place on Sunday afternoons in an open field. Marches, lilting Viennese waltzes, and German folk songs would fill the air that was also laced with the characteristic odor from the crematorium chimneys. Sunday afternoon concerts were an old German ritual, beloved by the middle class from Vienna to Berlin. One weekday an assembly of a different nature took place on this same field when a Kapo picked youths out of the various barracks and ordered them to collect there. He simply pointed his finger at a youngster and said, “You.” If you were chosen, you had to go. No explanation was given. Bernie was among the chosen.

About one hundred fifty youngsters assembled on the field. Many began to wail and sob, some clinging to each other, others looking desperately for a way to return to their barracks. Standing among them, Bernie thought, “This is it. I'm going to be hauled off and killed.” Under the watchful eye of the guards, the children milled around for about half an hour. Then, just as suddenly as they had been ordered to gather, they were told to return to their barracks. Bernie has no explanation for the sudden change of orders. Had there not been enough guards available to supervise the killing? Had they run out of poison gas? Had the group of youngsters become too upset and disorderly to dispatch them efficiently to the gas chambers?

As Bernie recalls this part of his story, it takes on an inexorable, breathtaking progression, a “no exit” inevitability. I ask him if we can take a break. While he goes out to the kitchen, I stand up and look out the large bay window of the den of the Rosners' home into their tree-lined garden. I see that the shadows are growing longer. Even in northern California, early spring days are still short. I become aware of the ticking of a clock. I listen for birds outside to offset the tight grip Bernie's recall has on me. But there is no escape. The death machine has been conjured up in his living room. No time at all has passed since Auschwitz. At this moment in the present, I understand that no bridge to Bernie's side, to his past experience, can be completely crossed by anyone who was not there. My attempts will ultimately remain inadequate. Nevertheless, I take up the challenge to find something, anything in myself to come closer to this other side, to attempt at least a partial crossing. And I am thrown back on my own experiences for help.

About nine months after the fall of the Berlin Wall and shortly after our visit to Tab in 1990, Sally and I were in East Germany to visit Goethe's Weimar and, a few kilometers outside it, the concentration camp at Buchenwald. The camp was now a museum run by former East German guards in charge of official German Democratic Republic “antifascist memorials.” We entered the barracks at one end and then followed the directional arrows from one room to the next, part of a long queue of visitors. When the queue moved, we moved. I found something uncannily mechanical in this inevitable forward thrust of the line, and about halfway through, I simply had to get out. It wasn't the horrors displayed in the exhibits but rather that I suddenly couldn't bring myself to take another step within this slowly moving crowd. I told Sally I had to leave. She understood, and we left the line and moved against the flow of the one-way human traffic. There was room to get by the other visitors, so we didn't impede anyone else's progress. But it was against the rules, and we had to pretend we didn't understand German when the guards barked repeatedly, “Falsche Richtung!” at us. Wrong direction? To hell with that! I was going to go against this flow, no matter what they said, propelled by a claustrophobic need to escape. As we were exiting where we had come in, Sally cracked a black joke in English that the guards wouldn't have understood: “What is this, a concentration camp or something?”

When we were outside in the sunshine again, I thought about the authoritarian behavior of these guards. Was their response to our unusual motion a vestige of the Nazi mentality that still operated in them, of old Prussia or of communist totalitarianism? Are there cultural patterns and mental habits so deeply and subtly ingrained in a population that individuals fail to see and therefore never change them? Will certain aspects of this mentality inevitably be passed on from one generation to the next, part of a cultural legacy? I fervently hope not, but I'm not sure. I only know that we could reverse our direction in that summer of 1990, in a place that by then was only a museum. But in 1944, Bernie and his family members could not change the direction of the steps they were ordered to take by the SS guards at the Auschwitz death camp.

Bernie comes back and opens the two bottles of Heineken that have been sitting untouched all this time on the low table in front of us.

Bernie's story did not unfold quite as easily as this retelling might suggest. Yes, he had decided to tell his whole story to me, and yes, he wanted the facts to speak for themselves. Yet we were two years into the project before he volunteered to tell me about the heartrending plaint in which inmates sang out for God's help in Yiddish from their barracks at Auschwitz during the night. He didn't sing the song—and I didn't dare ask him to do so—but rather dictated the text to me. He agreed to have his recall checked for linguistic correctness by a Berkeley expert on Yiddish, who pronounced Bernie's dictated text “letter perfect.”

It took me some time to understand the deeper cause for Bernie's initial silence. I knew that Bernie's family did not speak Yiddish at home, although many of the Orthodox Jewish families in Tab did. The history of pogroms and the Holocaust is woven into the fabric of Yiddish. Bernie has an aversion to telling his own story as victim. He wanted it to be the story of a survivor. He wanted the yellow star that his mother had to sew onto his clothes before their deportation to Auschwitz to remain only on his clothes, not to penetrate to his skin. By rejecting the role of victim, he preserved a freedom he needed later on, but by doing so, he cut himself off from part of his own history. Did I, in turn, wear the swastika on my pre-Hitler Youth uniform only as an external sign, as I believe? And, like Bernie, did I reject that mark of Cain to gain the freedom I needed later to live my life fully? We both believe that the crossing of our paths was only possible by not allowing these symbols to define our souls.

July 1944 had been hot in Germany, too. I remember it well, because it was the last summer before the end of the war, and I was working in wheat fields owned by my stepgrandfather. We took three breaks during the day. Late in the morning we drank coffee from a large tin can. At noon we had a small lunch of bread, followed by another break in the midafternoon. No one wore a watch, so village church bells marked the time of day. Apple trees were everywhere, but we benefited from their shade only when we happened to bundle up the cut wheat sheaves underneath one of them. Only the air raids sometimes allowed us to take a longer break. Then we would stop, gather underneath a tree, watch the passing show, and cool off.

Daylight Allied air raids were a regular part of everyday life all over Germany at this time. In the countryside they took place less frequently than in cities, and then they often occurred when stray bombers that failed to reach their goals unloaded their bombs at random, sometimes wiping out entire villages.

To me, real danger usually seemed far away. The protective shield of immortality that surrounds a thirteen-year-old worked for me. Bernie also imagined that such a shield existed. It became apparent in the way he described his early days in Auschwitz. But, as I was to find out later, when he continued with his story beyond Auschwitz—to Mauthausen, Gusen, and finally Gunskirchen—that protective shield, fragile and imaginary as it was from the beginning, was shattered. Death finally reached directly for his heart, flesh, and bones.

Nothing comparable happened to me. But there was the day when two friends and I were strafed by an Allied plane—a U.S. Air Force Thunderbolt—as we rode our bicycles over open fields. We melted into the ditch next to the road as the plane crossed our path from left to right in low flight. We were not hit, and when, after a few minutes, the fighter plane didn't come back, we broke out in excited laughter. We returned unscathed to our homes to recount our brush with death to anyone who would listen. The danger had lasted no more than a few seconds, not days, weeks, or months. What's more, we were not alone. We had our families, our own beds, and the familiarity of our homes. The odds for remaining alive were infinitely less for Bernie than for me.

On arrival at Auschwitz, Bernie was kept alive by one small movement of an SS guard's hand. What about this SS guard? Was there any difference between him and his fellow henchman with whom he shared the task of splitting the column of people into the living and the dead? Surely there was no difference in their relationship to the death machine they served, but for Bernie the difference between the two anonymous guards was enormous. One of them made a gesture, perhaps a random one, that kept him alive. No, on second thought, it was not random but routine, a routine decision of this guard that was a part of his repetitive job in that well-functioning system. Bernie thinks that perhaps the guard did not like it that the youngster moved left without being told to do so and therefore decided to assert his authority by sending him in the opposite direction.

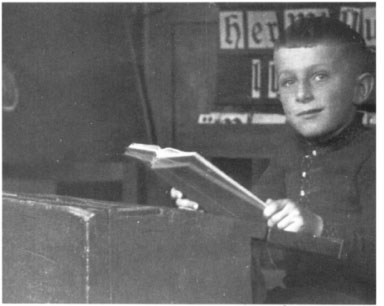

About the same time that Bernie was deported to Auschwitz, I was sent, over the protests of my stepmother, along with five other students in my Gymnasium at Miltenberg, to attend a Nazi training and selection camp. Called a Bannausleselager, it was designed to develop the future leading cadres of the Third Reich, and it constituted a prerequisite for being admitted to the higher-level, so-called Adolf Hitler Schule. My stepmother, opposed to the Nazis, had the courage to protest the decision to the Nazi youth authorities, but she was not successful in preventing my participation.

I left Kleinheubach for almost two weeks of intense physical exams, all kinds of intellectual aptitude tests, ideological indoctrination, and mental grillings that lasted all day and often into the night. Each day started with a roll call. As the camp leader made his appearance to review us, our immediate superior barked out, “Achtung! Stillgestanden! Bannführer, melde gehorsamst” (Attention! Camp leader, I report most obediently). We would snap to attention. Sometimes we were roused in the middle of the night and made to march to nowhere in particular; screamed orders had us drop into ditches on either the right or the left side of the road. We were told to act out imaginary battles against invisible enemies. I have always been claustrophobic by nature (unlike Bernie, I had the luxury of time to reflect on my psyche), so it was no more than an ingrained, knee-jerk reaction to resist the type of rigid discipline to which we were subjected.

Once we had to march out of the camp into an open field about an hour before sunset. We were made to stop, form lines facing the setting sun, and perform knee bends while our leaders strode up and down the columns monitoring us for proper execution. Those of us who began to groan as the unending knee bends became painful were singled out for derision. Others, after more time had passed, started to cry, and a few of us fell down from exhaustion. All of these “weaklings” were moved out of the ranks and made to stand apart in a group of reprehensible failures. As one of the shortest in the group, I avoided bending my knees altogether by simply bending over from the waist. Whenever one of our leaders approached my position in the second row,1 performed knee bends, as ordered, but returned afterward to my more comfortable subterfuge. By the time the sun touched the top of the mountain, about an hour after the exercise had started, the ordeal finally came to an end. While most of my compatriots dropped to the ground, I was able to remain on my feet and enjoy a sense of exhilaration for having eluded the watchful eyes of our guards.

Toward the end of the two weeks we were lined up outside the office, actually just a converted bedroom, for “racial classification.” When my name was called, I entered the small room and found one camp leader sitting directly in front of me, another at a right angle to my left, and a third, the scribe, in a corner of the room. The fellow in front pronounced me a “Westphalian-Aryan” and gave a thumbnail description of my physical appearance. For him, the shape of my face and my blue eyes qualified me for this category in the Nazi racist taxonomy. Then the fellow at my side piped up and added, “Strong Dinarian features,” referring presumably to my prominent, aquiline nose and dark hair. I found out later that these racial taxonomists used “Dinarian” for any German who looked “Mediterranean.” More than anything else, this strange ritual struck me as nonsensical. How could their categories refer to me, Fritz Tubach, who had always been proud not to have been born in Hanau, Frankfurt, or Miltenberg but in San Francisco, California? I felt myself to be not this or that; I wanted to defy any categories they would impose on me and be different from everyone else. I had gone so far as to sport a beret with an Edelweiss symbol on it (the symbol of the White Rose resistance group of the Scholl siblings in Munich) and had been ridiculed for it in the village. A Hitler Youth leader who sat next to me in church even accused me of being a member of the resistance and tore my beret trying to remove the symbol. I was not a part of the resistance, but I protested that I had a right to wear whatever I liked.

The camp latrine was a rustic construction with a round hole cut out of a wooden board. The rim of the hole was soiled, and I hated using the latrine. But on the last day of camp, when I had to go, I climbed up on top of it to avoid making contact with the repulsive wooden board. When I unbuckled the belt of my uniform and squatted over the hole, my dagger, adorned with a swastika and an oak leaf, slipped off and fell into the pit of human waste. There was no way to retrieve it, and when, after my return home, I told my stepmother that I had lost the dagger in the latrine, she laughed and said good riddance. She never replaced it for me. My father would have.

My father and stepmother had opposite reactions to my uniform. He associated many of his ambitions with Nazi emblems. Once he fantasized that after the war was won, all members of the Nazi Party would be given white uniforms. He looked forward to this prospect. When he took me on a train ride to Frankfurt during his last furlough, he decided that we both should wear our uniforms, he his officer's regalia with pistol holster and I my Jungvolk uniform and dagger. The upholstered first-class compartment was unoccupied, so we both had window seats. My father encouraged me to stand up most of the way to look at the landscape sliding by but also to be seen whenever the train pulled into a station en route to Frankfurt's Hauptbahnhof.

In November 1942, when I was almost twelve, my stepmother forbade me to see a movie about Bismarck that the local Nazi youth authorities had ordered members of the Jungvolk to see, in uniform. I disobeyed her, and when I came home she threatened to spank me. I told her that she could not touch me while I was in my uniform. Her answer was an immediate thrashing. She had strong hands from her work in the fields. In anger I went to my superior, a fourteen-year-old group leader. He showed up in uniform at my grandfather's blacksmith shop to confront him, and only because the boy was faster than my aging grandfather did he avoid a beating, too. The matter was put to rest when the father of this youth, Herr Stahl, who owned a lumber mill, came and thanked my grandfather for putting his son in his place. Until it resurfaced in my own memory work much later, this was a moment I had forgotten, because it did not fit into the cohesive past I had constructed for myself over the years.

To this day I thank my stepmother for her success in preventing my “promotion” from the Jungvolk to the Adolf Hitler Schule. We were called before a Hitler Youth tribunal because she hadn't allowed me to apply to the school even though I had passed the first hurdle of the camp, the Bannausleselager. When she was warned by the Hitler Youth official that she would ruin my career, she replied, “You worry about your career, I'll worry about his.” What if she had not been fully in charge of my upbringing at this point in my life but rather my absentee Nazi father or my beloved grandmother, who would have been proud to have her favorite grandson rise in the Nazi ranks? Would I eventually have given up my need to be different and ended up wearing the uniform of death? I refuse to believe so. But I recall a trivial incident that indicates how Nazi indoctrination was not simply hammered into one but was also insinuated into a young mind in a variety of subtle ways.

During the Bannausleselager, one of the twelve boys in my dormitory had brought along a condom. We blew it up like a balloon and floated it out of the window into the courtyard. Camp leaders seemed enraged by this prank. Their investigation traced the infraction to our quarters, and we were grilled for hours, pressured to reveal the culprit, and threatened with severe punishments. At the same time, however, I detected a certain ambiguity in these interrogations, which obviously implied an underlying compliment: “Ihr seid Kerle” (You're real men). We stuck together, refused to betray the instigator, and escaped punishment. The double message of our superiors linked a number of factors—sexuality, transgression, regulations, and male solidarity—that served both to maintain order and to inculcate in us a sense of rebellion and team spirit. They wanted to make us capable of doing anything in service of the grand Nazi design. They encouraged us to develop into a controlled horde, a gang, really, legitimized and led by the greatest tribal chief of all time, who sat in Berlin.

At this point, Bernie and I wanted to continue our recollections with as few interruptions as possible. His story influenced the present to the extent that it was uncomfortable to stop and pick it up too many days later. It seemed to me almost as if leaving Bernie's narrative on that path to his barracks in Lager E added to the length of his stay in the concentration camps. So we met again a couple of days later, this time at my house. Bernie continued recounting his memories in our living room, and I took notes as usual, interrupting him for details of description and chronology. I was amazed at the cool detachment with which he drew with a few sure strokes on a blue-lined sheet of yellow paper a map of the Birkenau section of the Auschwitz concentration camp. He drew arrows to show me how people were moved to the various campsites, to delousing, to extermination stations, or to the outside, either as part of temporary work teams or as permanent transfers to other camps. His precision stunned me. Was it Bernie's clarity of mind that increased his chances of survival against overwhelming odds? Did his mental toughness, of which he is proud even today, protect him from going under psychologically? Or was it the twelve-year-old s feeling of invincibility that kept him sane and flexible, thus increasing his awareness of the few small opportunities that enhanced his chances? It is difficult to weigh these factors, knowing with the benefit of historical hindsight that the flick of a hand of an SS guard could at any moment snuff out any life, weak or strong, any mind, lucid or muddled.

Bernat Rosner was assigned to Lager E, a “quarantine camp” next to Lager F, which bore the official euphemism Hospital Lager, where Josef Mengele performed his barbaric medical experiments on living human beings. Bernie remembers the twins who were taken from his section of the camp and assigned to Mengele s adjacent experimentation station. He and other inmates talked to these twins across the fence. When they found out that they were well fed and well treated at that moment, they envied the twins and wished, unaware of the diabolical fates that would follow, that they could join them.

A careful observer, Bernie became aware of the process by which inmates from the “quarantine camp” were selected either for placement in a permanent work camp at Auschwitz or for transfer to other concentration camps. Only inmates selected for placement in a permanent work camp at Auschwitz received blue tattooed identification numbers on their forearms. Since Bernie's initiative led to his transfer elsewhere, he does not bear this mark on his body.

The facilities used for the selection were located in Lager E. They consisted of large, elongated blockhouses that were divided lengthwise into two sections by a four-foot-high wall. These barracks were initially constructed as stables, and the wall, hollow inside, served as a conduit for heat generated by a stove near the entrance. A separate door served each half of the barracks.

The process of selection consisted of gathering the inmates outside the barracks and then herding those selected for transport into the righthand side of the divide. As time passed, Bernie noticed that the pool of inmates left behind—the group not designated for transfer—was made up of older and sicker persons and of young boys who were less fit for work. It gradually dawned on him that it would be dangerous to remain behind indefinitely with this group.

One day, when a new selection was under way and Bernie again had not been chosen, he took his chances and decided to jump over the wall to join the inmates on the right side. A guard, positioned to prevent any such crossovers, pinned Bernie's arm to the wall he was attempting to cross with his boot. For a brief moment the guard looked at him while he held him there. Then he shrugged his shoulders and lifted his boot, allowing Bernie to join the group selected for transport. Bernie's desperate decision and the Nazi guard's random act of forbearance removed him for the moment from the immediate grip of the death machine. And because of this leap, a correction needs to be made in the official record of the number of inmates put on a transport on September 17 from Auschwitz to Mauthausen, as recorded in Danuta Czech's Auschwitz Chronicle, 1939-1945: From the Archives of the Auschwitz Memorial and the German Federal Archives. The entry in question, recorded for September 17,1944, lists 1,824 prisoners, among them 1,396 Poles. With Bernie's self-selection, the number of prisoners was actually 1,825.

The more than 400-kilometer transfer to Mauthausen by cattle train took about two days. It was quite a different ride than the one that took Bernat Rosner to Auschwitz several months earlier. There were no women or small children in this group, no acquaintances from his native village, and no members of his family. All the passengers were men in relatively good shape, with Bernie the youngest. The cattle car doors were kept open, and in each car two German SS guards rode with the inmates on their way south. While the train was stopped temporarily in Czechoslovakia near Olomouc, Allied planes dropped bombs near the train but failed to hit it. The pilots must not have known that the cattle cars were filled with human beings. And, of course, the Nazis would not mark such a train to prevent it from being attacked. After the air strike, the train started moving south again. None of the inmates aboard had any idea what their final destination would be.

Bernie started up a conversation with one of the German guards, who took an interest in him. The guard asked Bernie where he came from, and the two of them talked for a long time while the train rolled on. I tried to picture this extraordinary situation, because it seemed so simple and ordinary on a certain level—two strangers who find themselves caught for a couple of days in the same place pass the time in conversation. Bernie interrupted my attempts to interpret this incident by saying that this SS guard was “just an ordinary guy.” His remark surprised me. So the guard was just a regular guy caught in unusual circumstances? In other words, he was just doing the job to which he was assigned? We both know this to be a macabre, yet believable, point of view.

The train arrived on the evening of September 19,1944, at a village on the Danube. The passengers spent the night in the locked cattle cars and entered the camp only the following day. On their walk up the hill toward the high-walled camp, Bernie remembers the intense longing he felt for the everyday life that seemed to emanate from the houses of the village and the fields surrounding it. When they reached the imposing entrance of the camp, with its solid stone walls and huge gate adorned with the eagle and swastika of the Third Reich, they tried to speak with members of work details leaving the grounds but were prevented from doing so by the guards. They had arrived at the concentration camp of Mauthausen. On September 21, 1944, the list of arrivals from the previous day, Bernie's official arrival day, was typed in the camp records, the Liste der Zugänge vom 20. September 1944. In this list the following entry appears: “Rosner…Bernat…29.1.27…Budapest…Landarbeiter” (farmworker), and to this was added his number, “103,705,” right after Rosenfeld, Erno (103,704), a Hungarian farmer born in 1905, and before Rotberg, Pinkus (103,706), a Polish machinist born in 1908. The Mauthausen entry contains an important error, again occasioned by Bernie's own initiative — namely, his decision to change his year of birth (1932) on the record to 1927 in order to make himself appear five years older than he was. Although this lie did not assure his survival, it at least gave him a chance to be counted among the work-qualified adults rather than among the younger teenage boys who would almost automatically be eliminated from consideration as laborers.

Mauthausen was divided into three sections. The oldest section, Lager 1, was subdivided into thirteen blocks and held German criminals, who, as “Aryans,” enjoyed superior status and special privileges. Wearing green triangles on their jackets to signify this status, they were given supervisory roles in the camp. Willy, an Austrian criminal, supervised Bernie's barracks. Polish or Ukrainian non-Jews wore red triangles signifying their lower status. At the bottom of the camp hierarchy were the Jews, who were required to wear yellow triangles. Bernie, the youngest of a group of about twenty teenagers who were part of the same human shipment from Auschwitz, was assigned to Lager 2, block 21. Along with the others, he was given a uniform and a haircut called the “Mauthausen-Strabe”—their heads were shaved down the middle.

Aside from the Nazi-imposed hierarchy, various group identities developed among the inmates, based on their backgrounds. The Hungarian Jews made up one such subgroup. The one language all groups had in common was the language of their oppressors —German —or rather a kind of pidgin German most had learned in the various camps.

During the daytime, inmates were herded outside, where they usually spent their time standing about idly in the increasingly cold and wet weather of late September and October. They huddled together for warmth, and one of the amusements of the SS guards and the Kapos was to club those standing on the outside perimeter of the group so that the whole group of prisoners would break into a panicked stampede and trample each other. In one of these melees Bernie sustained a slight leg wound that developed into a sore that wouldn't heal. He did not seek medical help, however, for fear his injury would mark him “unfit for work,” a death sentence in the concentration camp.

At night inmates were jammed together, often four abreast on a narrow platform bed in unheated barracks. To avoid the almost unbearable crowding that prevented sleep, Bernie made a bargain with his other bedmates for one of their blankets in return for giving up his assigned space in bed. With this second blanket, he hunkered down on the floor below the bunkbeds that were stacked up three high above him. This gave him and his bunkmates a little more space. Bernie gained a partially covered area provided by the bed immediately above him and, most important, another blanket that provided extra protection from the cold.

Beyond the cold, there was hunger. Rations were limited to a quarter loaf of bread per day with either a pad of margarine or a slice of liverwurst, a bowl of cabbage soup that usually contained maggots, and, in the morning, lukewarm brown water that was called coffee. Only non-Jews received cigarette rations, on the rationale that Jews would only use the cigarettes for “profiteering.”

As time went on, hunger turned into starvation and many of the inmates began to waste away. The most emaciated among them, the ones who could barely be distinguished as being dead or alive, were given the odd name Musulmänner (Muslims). Teenagers like Bernie worked in the kitchen, where they filled their days with endless reveries about food —about eating meals in warm houses with tables laden down with meats, bread, fruit, vegetables, and sweets of all kinds. The work in the kitchen provided Bernie with an occasional chance to supplement his meager food ration. He made a deal with the other kitchen help that allowed him to smuggle potatoes and onions into his blockhouse. Because his concentration camp uniform was too large for his small body, he could easily stuff it full of the precious vegetables without arousing suspicion before returning to the barracks. On one occasion his pants and jacket burst open as he arrived at his blockhouse, and potatoes and onions spilled to the ground at the very moment an SS officer entered. Both the inmates and the officer broke out in spontaneous laughter. Bernie lost his treasures but suffered no other ill consequences from having taken this dangerous risk.

Vegetable smuggling was not the only survival strategy developed by desperate boys in the camp. Among the relatively more privileged German inmates were a number of homosexuals, and some of the boys prostituted themselves to these men in exchange for food and a degree of protection. It was, in fact, the discovery of one of the boys caught in the act with a Kapo that ended Bernie's and the other teenagers' brief stint of kitchen work, a rare interval during his concentration camp stay when he was not starving.

Every morning and evening a general roll call was held. All the inmates had to leave their blockhouses and line up outside to be counted. The head of the cell block, the Austrian criminal, Willy, would then shout, “Achtung! Stillgestanden, Miitzen ab!” (Attention! Caps off!). Then he would turn to the SS officer in charge of the Appell and bark, “Herr Oberscharführer, ich melde gehorsamst” (Herr Sergeant Major, I report most obediently). The head count followed.

As the days, weeks, and months at Mauthausen passed, the routine, complete surveillance and total control in the camp established an illusory sense of predictability. At least for a boy of thirteen, it was possible with a bit of luck to increase one's chances of survival to a small degree. After all, as Bernie said in a matter-of-fact way, “In Mauthausen you were killed only if you became sick” (During his internment, he did not know that the laws of murder were different in other parts of this large camp and that Russian POWs housed in nearby barracks were tortured and killed, especially after a major escape attempt.) From his own subjective point of view, the margin of safety seemed to be a little greater around his body here, wider at least than when he lived next to the extermination ovens at Auschwitz. He was spared any significant illnesses that might have been noticed by the guards. So, for a time, his youthful invulnerability worked for him, at least until the day he found himself on the quarry steps.

There was a quarry within the Mauthausen camp boundaries where selected inmates were forced to carry stones, back-breakingly heavy stones, up a long, steep set of stairs from the bottom of the quarry to the top. It was organized for two purposes, one of them being camp construction. But its main purpose was the destruction of human lives. Mere extermination was not enough to satisfy the sadistic urges of the camp authorities, so they devised this ingenious way to torture their prisoners to death on this via dolorosa of crude steps. Laden with heavy stones as they ascended the narrow, torturous steps, prisoners were driven continually up and down without mercy, without stopping or rest. These quarry steps existed for Bernie only one day, the day he was forced to work there. Just on the day Bernie worked, half a dozen people dropped around him and died of exhaustion or were killed by the SS guards. The prisoners who faltered, or who failed to move fast enough to satisfy the guards, were shoved so that they tumbled to the bottom of the pit, still clutching heavy rocks to their bodies. Why didn't they let go of the rocks as they fell? Bernie doesn't have an answer and comes back to that question over and over again: Why didn't they let go of the rocks? Half-dead inmates removed the emaciated bodies of the dead like garbage, so that still others, who were already starved nearly to death before they ever reached the quarry, could take their places. Thus were lives turned into dead matter. This was more than a nightmare. For Bernie, it was a day in hell.

Hours passed, during which the present was obliterated for both of us. But suddenly we realized that we had to end our session of recalling the past, so we left the steps of Mauthausen behind. Bernie had to rush to meet Susan at the Bay Area Rapid Transit station. They were going to San Francisco for the evening. I accompanied him out the front door to his car. He told me he had just taken a bad spill on his bicycle the day before but hadn't been hurt in the least. He looked at me and said, “You know, I must be a very tough guy.” I smiled at him and said nothing. As he unlocked his car, he turned to me once more and smiled back with a touch of irony. Then he said, with more insistence, “I'm tough as hell.”

It was a long time after he told me about the quarry and even after our visit to Mauthausen that I asked Bernie why he had worked there only one day. I had always accepted this one-day event as self-evident. But, of course, many were worked there repeatedly until they died. It was a particularly cruel form of extermination. Bernie answered me in his usual straightforward, unselfconscious way.

He couldn't be sure, he said, but he had a theory about it. His arrival at Mauthausen happened to coincide with the arrival of the first full contingency of boys. Since there had been no young people there before, it “made news”; it “created something of a sensation,” as he put it. The boys were housed in Bernie's block 21, whose Blockältester was the Austrian criminal, who seemed to have retained a touch of humanity. Bernie believes that this man knew that people chosen to work in the quarry wouldn't last very long. And when he saw how these youths, including Bernie, looked after their first day at the quarry, he simply decided not to pick them again and had them work instead in the kitchen for a time. The Blockältester retained a degree of discretion in making such selections, and Bernie credits him for having made the decision that saved him and certain others from further exposure to the deadly quarry.

Today Mauthausen is a quiet Austrian town on the Danube River. The charming city of Linz, known for centuries for its Linzer Torte pastries and generous hospitality, is not far away. Mozart visited Linz frequently and dedicated one of his symphonies to it. Across the Danube, just a few kilometers away, stands the church of St. Florian, with its finely chiseled baroque decorations and Anton Bruckner's monumental crypt. Its lovingly tended cemetery is full of neat crosses, flowers, and quaint inscriptions on marble tombstones that describe the profession and status of deceased loved ones. St. Florian and Linz have become favorite tourist stopovers for travelers on their way from southern Germany to Vienna, bypassing Mauthausen on the other side of the river.

For Bernie, Mauthausen in autumn and winter of 1944-45 did not connote music, pastries, and baroque architecture but cold, starvation, and steep quarry steps. The Allies moved across the German border in the West while the Russian army reached the German border in the East. The Ardennes offensive in December 1944, launched by the German army to cut off the northern British flank from the Americans farther south, temporarily halted the push of the Western Allies into Germany. This last winter of the war turned out to be very cold all over Europe. Liberation was still far away.

About 500 kilometers northwest of Mauthausen, I attended school in Miltenberg, a few kilometers upriver from Kleinheubach in the Main Valley. Today a fast driver can cover the distance between Mauthausen and Miltenberg in less than six hours on the Autobahn. In my village, I knew something about both cold and hunger but nothing about starvation, let alone the stone quarry steps of Mauthausen. Although there exists no equivalence in degree or kind to our fortunes, as World War II in Europe reached its climax and finally came to an end in spring 1945, our individual lives were both caught up in this maelstrom of destruction, Bernie at its center and I at the margin.

Occasionally, when my family wasn't home, I tuned in to the BBC London radio broadcast in German—a forbidden activity— because I enjoyed comparing Allied reports about the progress of the war in France with the reports from the headquarters of the German army. Aside from this “secret knowledge,” I and everyone else knew that the German army had performed retaliatory mass executions in villages all over Europe that were suspected of having harbored partisans. These executions were deemed justifiable acts of war, legitimate retaliation for enemy activities behind the German front lines. Beyond that, for years there had been ominous whispers at home about the SS knocking on doors in the early morning hours to arouse German victims and take them away. “Nacht und Nebel-Aktionen” they were called, actions enshrouded in fog and night that shunned the light of day, that were best ignored by “law-abiding citizens.” I recall that the actions taken against the Jews in our midst did not meet with the same degree of dread as did these actions against the few non-Jewish Germans who had run afoul of Nazi laws. Even my father, a loyal party member, told us about his near-panic one day when he was visited without warning by the Gestapo, who wanted to know details of a business trip to England he had taken a few weeks before the beginning of the war. The Gestapo was satisfied with his explanation and didn't bother him again, to my father's great relief.

Concentration camps, or Konzentrationslager (KZs) in German, were not discussed. A taboo against speculating openly about what might go on inside their walls was firmly in place. Any such speculation or questioning was dangerous. With this lack of communication among Germans, it is difficult to find out exactly what was known and by how many. What did I personally know about Auschwitz or about other concentration camps in 1944 when I was thirteen years old? I knew for sure what had happened by May 1945, when I was fourteen and a half, after the victory of the Allies. But what did I know before that time? I was an alert boy who collected the leaflets dropped by Allied planes—forbidden papers that fell from the sky, from another world. I knew I was breaking the rules, but the heady enjoyment in the transgression was too great for me to stop. I don't remember ever reading anything about concentration camps in those leaflets, or, if they were mentioned, I don't recall it. If death camps where millions of Jews were being exterminated in gas ovens had been mentioned, I'm sure almost everyone else in the village would have considered it anti-German propaganda. That describes my limited knowledge of the world as a thirteen-year-old before the Allies arrived. I cannot answer for all Germans.

Hunger came for me in small daily doses, and as the winter progressed, my daydreams became more and more vivid. I was fourteen years old and convinced by then that Germany would lose the war. I kept a typewritten diary of the Allied landing on the coast of Normandy, and when the Germans failed to contain these troops on their beachheads, I decided all on my own that this was a sure sign of eventual German defeat. I reasoned simply that since the British Channel and the German Atlantic wall were breached, there was no impediment to the Allies of that magnitude left between the open French countryside and Germany. The Rhine was a lot smaller, after all, than the British Channel. Anyone interested in geography would know that, I told myself. But I did not share this view with anyone. I kept it even from my grandmother, who surely would have considered me mentally unbalanced. When the war was over, I thought I would return to the United States, the country of my birth, and work in a chocolate factory where I could eat as much candy as I wanted.

Although there was no chocolate to be found in Kleinheubach, potatoes, preserved vegetables, and bread were always on the table. We consumed our small meat rations on Sundays, when, unfortunately, patriarchy reigned at the dinner table. My stepgrandfather would carve up what was invariably a miserable chunk of beef or pork, take the largest portion for himself, and hand out the rest in pieces of diminishing size based on our ages. As the youngest, I received the smallest piece.

In geography at school we were given instruction about northern Europe. The teacher, a large man with a pointed nose and thinning blond hair, stopped in the middle of his lecture and had us recite after him, “In Denmark, there is cheese, ham, butter, eggs, and fresh fish.” We eagerly repeated this sentence in chorus, echoing his words louder and louder, as if by conjuring up these appealing culinary images, we might be able to make them appear in front of us.

Our Latin teacher tended toward fanaticism. Once, during an air raid alarm, he refused to let us go to the shelter with the exhortation, “Even if we lose the gun battles, we must be prepared to win the battles of the mind.” We, of course, had not studied for the examination he had planned and hoped that the air raid sirens would cancel it. Except for the best student in the class (who later became a professor of Greek at the University of Freiburg), we all flunked that Latin test. For me, school had become a cumbersome diversion. Real life and the war happened outside the classroom.

Nighttime air raids disrupted our sleep more and more. The peaceful walks under the stars with Schloßtante, when she had taught me the names of the constellations, were replaced with a different ritual. By the intensity and direction of the glow, we learned to distinguish which of the surrounding cities — Heilbronn, Wiirzburg, Darmstadt, or Frankfurt—were being bombed. By the end of the war, it was easier for me to extend my arms, with the accuracy of compass points, in the direction of these cities than it was to identify the constellations I had learned earlier.

Months before the war ended, our hunger had become a constant, gnawing presence, like a chronic pain with no relief. Luck had it that a military boat loaded with wheat became marooned in the Main River near Kleinheubach. Villagers scrambled aboard and threw the soldiers who guarded it into the water. Then word went out that the wheat was ours to take. All night we filled every available container. Families with bathtubs were especially fortunate. They were able to store enough wheat for their own use plus some extra for bartering. About 8 kilometers down the river another boat filled with heating oil had been abandoned. This boat was raided, too, and village women tried to render the oil edible by heating raw potatoes in it. (The raw potatoes were said to absorb the residual poison of the oil.) The resulting oil tasted dreadful and made many people sick, but after a time our digestive tracts got used to it. Through such strategies we got by in the village, hungry often but never starving.

I sometimes wondered whether Bernie's lifetime professional association with the Safeway supermarket chain somehow related to his early experience of starvation. But he sees no connection. For myself, I still do most of the grocery shopping in our household because I feel good inside a well-stocked grocery store.

It was very cold in Kleinheubach during the last winter of the war. In our house, only the living room was warm enough to provide some comfort. The bedrooms were not heated. Everyone tried their best to avoid a trip to the outhouse during the freezing nights. On winter mornings, urine was frozen in our chamber pots, and ice flowers covered the windows all the way to the top. I remember that on the coldest days the edge of my blanket near my face had a hoary frost on its surface from my breath. My feet had grown too large for the only pair of shoes I owned and therefore continued to wear. Where the sides of my feet pressed painfully against the leather, I developed frostbite that itched even years later whenever my feet were cold.

To some small degree, I could refer to my own experience of hunger and cold to reach over to Bernie's suffering 500 kilometers southeast of me. But the quarry steps of Mauthausen and the profound impact they had on Bernie remained hidden from me, except during the very moments when he described them to me in my living room in California fifty years later. A surprise recall helped me to comprehend a little better the constant mortal danger he faced.

In 1943 I contracted tuberculosis and was sent for treatment to a sanitarium at Friedensweiler in the Black Forest. During the three months I was there, the other patients and I received routine care and examinations. At one point, however, we were called to our resident doctor's office where he along with two or three uniformed men were present. We were examined by this group individually. I remember that the officers spent more time reading my medical record than examining me. Although I was quite aware at the time that this examination was an odd departure from the normal hospital routine, nothing came of it.

What were these uniformed people doing at our hospital for tubercular patients? A few years ago, I read for the first time a newspaper report that plans had been made to eliminate “unfit” tubercular Germans. In retrospect, I realize that this incident at Friedensweiler, which had been different from anything I had experienced up to that point, might also have been a brush with the Nazi death machine. I have no proof of this, but neither do I have any other explanation for it.

Does my fleeting and vague, after-the-fact anxiety surrounding this strange event help me to understand the quarry steps of Mauthausen any better? Of what Bernie experienced I have only heard his retelling. What do I feel about it all? Sadness and shock, perhaps, because these things happened to him, to my friend. Surprise? No. Sympathy? It's too late. Bernie doesn't need it. I can't experience the physical or emotional pain he went through. Now, with historical hindsight, I can at least understand on a rational level that the same death machine that threatened him continuously may also have crossed the horizon of my own life for a brief moment. I now remember that peculiar incident in my youth with a cold shudder.

As inmate number 103,705, Bernie had been turned into a manageable and disposable quantity. A transfer to another camp or reassignment to another section within a camp could swiftly become a matter of life or death. The homosexual incident in the Mauthausen kitchen precipitated the transfer of all teenagers from Lager 2 to Lager 3. There Bernie was assigned to block 27, where the conditions were more squalid than anything he had yet encountered. The campsite was no more than a muddy corral. The origins of the inmates were more varied. Not only Eastern Europeans but also Spaniards, Frenchmen, and even some Americans were imprisoned there. Aside from the diminishing daily rations of bread, the only food was a bowl of soup a day that was almost inedible, topped as it was by a layer of grease that made Bernie sick to his stomach. Such a decline in the quality or quantity of food was a direct threat to survival. The margin was shrinking. The danger of becoming near-dead, of joining the ranks of the Musulmänner, drew closer. A debilitating sickness, a bad case of diarrhea, even if transitory, could mean extermination. Keeping your eyes and ears open came to make less of a difference. But when the margin disappeared, there was still luck. There were random situations that helped Bernie as life in the camp deteriorated further.

It so happened that the Blockältester in charge of one of the barracks in Lager 3, a German criminal, befriended Bernie, the youngest of the inmates. As his helper, Bernie ran errands, sang songs, and helped clean his living quarters. In turn, this inmate served as Bernie's friend and protector, temporarily increasing his survival chances. For two weeks, Bernie lived, as he put it, “the life of Riley.” He was allowed to eat regular food and to bunk down in the warm living quarters of the Blockältester. For two weeks he had a name, not just a number. His friend and protector ordered a special identification tag made for him by another inmate who had been a silversmith before internment. The tag consisted of a flattened spoon, fashioned into a little work of art with a design around its edges. A small chain was attached to it for easy wearing, and this oval-shaped amulet replaced the crude official identification tag, made out of a strip of tin can and wire, that was issued to all inmates by the camp authorities. The outer surface of this new bracelet showed his identification number, 103,705, while the reverse “hidden” side had engraved on it his initials, “BR.”

In telling me his story, Bernie hardly mentioned his family after their separation at Auschwitz. When I asked him about this, he told me, “The realization that my family was dead came to me gradually.” These were his precise words. He did not say that his family was “murdered” or “exterminated”; rather, he used the language of normal life that includes “death” as a natural event. But his family was exterminated, they did not just die, I thought to myself. The everyday task of surviving left him little time to devote to anything else, including reflections on the past or on his family that had disappeared. Their violent deaths in the gas chambers of Auschwitz leave a black hole in his very language that blocks Bernie from capturing these hellish facts in words. And I am rendered incapable of narrating anything. Nothing escapes from that black hole—no image, no cry, no suffering…no language.

My uncle who was assigned to drive oil trucks in Ploiesti, Rumania, was probably blown up—he disappeared without a trace— but most of my family members survived the war. Uncle Ernst, the communist who escaped service, watched the entry of the Allies into Ludwigsburg from his front door, applauding the victors with glee. Gentle Uncle Ludwig, who had been inspired by the party rally in Nuremberg, had been sent to the outskirts of Moscow and back as a front-line machine gunner. He lost most of his toes, part of his feet, and his mind in the freezing winter near Smolensk in western Russia. When he returned home, he would wake up nights screaming that the Russians were coming to hang him up by his toes, his “innerer Reichsparteitag” over.

My father's fate was quite different. In 1941 the German army assigned him to a job in the British Channel Islands as an Abwehroffizier (counterintelligence officer) of the General Staff located at Port St. Pierre on Guernsey. His main problem seems to have been the extra pounds he had a hard time shedding, at least until the German army supplies for the British Channel Islands were cut off after the Normandy landing in June 1944.1 remember a photo of him working up a sweat on a reducing machine. Another photo shows him standing on the steps of the Sacre Coeur in Paris, in the company of an SS officer. What was he doing with an officer of the SS? He told me that while on Guernsey he once ordered an English civilian sent to “a camp in Germany” for having hoisted a Union Jack and for singing “God Save the King” in one of the local movie houses. My father justified his deportation order by saying that the man wanted to be arrested and sent to that camp, to join his girlfriend who was already there. That was the only personal connection with camps to which my father ever admitted.

My father—unlike Bernie—had no difficulties obtaining a visa to come to the United States after the war, despite his Nazi and wartime activities.

Mauthausen was a center for several satellite camps, including Gusen, in the vicinity of which the German aircraft manufacturer, Messerschmidt, had a factory that built warplanes. In December 1944 Bernie was assigned to Lager 1 at Gusen, where he learned to drive rivets and cut out small metal parts used in airplane construction. The work site was located outside the camp, and although Bernie s group was under guard at all times, their march to and from the slave labor encampment gave them some physical movement outside the barbed-wire confines. As they walked through the open Austrian landscape, they could see green mountains, foothills that stretched to the Alps, a different world spread across the southern horizon. Bernie remembers that one day, as his column walked to the factory, an Austrian man working close by in a field dropped a half-eaten apple that Bernie was able to pick up. Bernie is convinced that the Austrian meant for one of the starving inmates to benefit from this piece of fruit. This unexpected bounty was the only piece of fresh fruit Bernie ate during the eleven months of his concentration camp imprisonment.

Those who left the camp on this work detail were considered useful to the German war efforts and less dispensable than the inmates left behind. In spite of their hunger and exhaustion, this group retained some hope and a grim sense of humor to describe their condition. As they were marched to work, they often sang a ditty to the tune of “Lili Marlene” with the lyrics, “Heute nicht arbeiten, Maschine kaput” (Today no work, the machine is broken). The war machine was breaking down, to be sure, but the breakdown had not yet reached Gusen. Fighter planes were still being produced to intercept the Allied bombers in their round-the-clock attacks. Bernie the riveter was forced to do his share to keep the German war effort going.

A second Lager reserved for Jews only was situated not far from Bernie s Lager 1 at Gusen. There was little contact between these two sections of the camp. After liberation, the survivors of Lager 1 discovered that the conditions in Lager 2 had been infinitely worse than in their own. It turned out, in fact, to be a horror camp, with regular torture, killings, and deliberate starvation. Few inmates from Lager 2 survived.

As time went on, however, the line between survival and death narrowed for everyone at Gusen. The total war that Goebbels had promised the world was beginning to be felt in the camps more and more. Exacerbating the routine brutality and squalor of the camps was the steadily deteriorating state of the overall German wartime economy. Camp conditions worsened as the ground war reached Germany. Not only systematic killings, but starvation and illness caused by the growing scarcity of food and other necessities, accelerated the extermination process in camps all over Europe.

Little more than half a year had passed since the Rosner family had been deported from its Hungarian village. An orange in Budapest on the way to Auschwitz and a partially eaten apple near Gusen on his march to work constituted the only tangible signs of support or sympathy Bernie received from the outside world. Inside the world of the concentration camps, there were the rare incidents of help that came to him from a guard or another inmate. But, above all, the indispensable survival condition for inmates within the camps was a buddy system—a survival unit composed of two friends who watched out for each other whenever possible.

Shortly after his arrival at Gusen, Bernie teamed up with another Hungarian teenager, Simcha Katz, a member of the original shipment of prisoners from Auschwitz to Mauthausen, to form such a survival unit. The ultimate test of this relationship came in mid-January 1945 when Simcha's shoes—the officially issued wooden-soled clogs—were stolen. For two days Simcha trudged to work through the winter ice and snow in his bare feet. If he was going to survive, he would have to repurchase his shoes from an inmate who used thievery as his survival strategy and who offered to “sell” Simcha his own shoes, which the thief claimed he had “found.” The ransom for the shoes was two days' bread rations, but such a great sacrifice would have spelled Simcha's death. The only way to save his life was for both boys to go without their bread ration for one day. This they did, and Simcha got his shoes back.

Bernie remembers December 31,1944, New Year's Eve. The Blockältester, the inmate in charge of block 15 at Gusen, turned out to be humane. Bernie no longer remembers the name of this man from Vienna. And he never knew what motivated him. The man obtained some alcohol and invited his compatriots who served in positions similar to his own to a party. Bernie and Simcha watched the drinking bout and celebration through the window from the outside. Right there in the middle of starvation and death, a party took place. Some participated, others watched. What were they celebrating? Having survived so far? Had the news of Allied advances reached them and given them reason to believe that they might be liberated? Was it merely an attempt to escape the horrors of camp life for a while? Had everyday life achieved some semblance of normalcy so that daily rituals, such as the celebration of holidays, observed in the outside world, could also be celebrated here? Bernie's description of this scene became frozen into a tableau in my mind: in the midst of mass murder, grown men drink and celebrate while boys look on.

I remember that same New Year's Eve of 1944 very well. During the winter, the circle of life had drawn closer around my family in Kleinheubach. Activities became more and more restricted to the immediate environment. Not only did Berlin, the center of Nazi power, seem far away, but even the distances between the villages in the Main Valley increased as the war went on. Five of us, my stepgrandfather, stepmother, two aunts, and I, sat in the living room around a small light fixture that pulled down from the ceiling. Rimmed with a green, glass bead fringe, it cast a dim light onto the table. We drank hard apple cider, a specialty of the region. Very little was said. Before midnight I went to bed in the room next to the living room. I lay there as the clock in the living room struck midnight. The radio was on, and I listened to the first movement of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony followed by an announcement I will never forget. With his hard-edged voice and sing-song pitch, Goebbels, the minister of propaganda, proclaimed that the ground was swaying below us Germans but that Providence and, even more than Providence, Der Führer would steady all of that in the coming year, which was sure to bring a final victory to Germany. I was rational enough to wonder, right there in my village bed, what the metaphor of the “swaying ground” really meant, realistically. The world had grown cold, dark, and dangerous around me — that I knew.

The year 1945 arrived, and the January weather grew increasingly severe. Allied bombing raids multiplied. For Bernie, there seemed to be some minor improvements in concentration camp life for a very short time. But conditions at Gusen deteriorated rapidly in February. The only inmates that Bernie recalls whose lot improved markedly were two who were assigned to work in the crematorium extracting gold teeth from the mouths of the increasing number of corpses that they processed. Some of this gold was surreptitiously passed on to German guards. If the inmates had been caught keeping any of the gold themselves, they would have been shot. But German guards were glad to pocket some of the dental gold and gave the inmates incentives in the form of extra food rations to participate in these macabre exchanges. Other inmates envied these crematorium workers and would have gladly taken on their job in hell for more food.

For everyone else, including Bernie's group of teenagers, who had remained healthier than the adults, the pace of disintegration quickened. Their eyes grew ever more hollow and sunken. Weakened physiques became skeleton-like, and more of them joined the growing number of walking dead. Lice multiplied on everyone. Corpses began to pile up, and pushcarts came by twice a day to pick them up.