Chapter 1

A historical whirlwind tour

Within a few generations of the rise of Islam, the new religion spread across a huge swath of territory, from the Iberian penninsula in the West to the borders of India and China in the East (see Map 1). Most of this territory still belongs to the Islamic world today, and more besides: nowadays Indonesia is the nation with the highest number of Muslims, and Islam is the second most popular religion in India. Naturally, it would be an exaggeration to say that philosophy has flourished in Islamic culture at all places and times. But the widespread idea that philosophy in the Islamic world declined, or even vanished, towards the end of the medieval period is equally false. This misconception is so deeply embedded that philosophy in the Islamic world is most often taught at university level as a part of medieval philosophy. Yet the full story goes well past the medieval period and down to the present day.

The formative period

The medieval period of Europe overlaps with most of what I am calling the ‘formative period’: the time up to Avicenna (d. 1037). Ancient Greek philosophy became known in the Islamic world a couple of centuries before Avicenna, but our story begins earlier, with the arguments that raged among theologians (mutakallimīn) in the 8th century. A good place to start would be Wāṣil ibn ʿAṭāʾ (d. 748), who is given credit for founding the kalām movement known as the Muʿtazilites. This label is slightly misleading. The early theologians spent much of their energy arguing with one another, and did not yet see themselves as adhering to a standard list of Muʿtazilite doctrines. Still, Wāṣil and several other early thinkers, especially Abī l-Hudhayl (d. 849), did hold views that would later be adopted by thinkers who thought of themselves explicitly as Muʿtazilites.

The Muʿtazilites were styled as ‘the upholders of unity (tawḥıd) and justice (ʿadl)’, a phrase which gives us a good way into seeing how their theological doctrines hung together. They were staunch defenders of God’s unity—not exactly a controversial stance, given that the core teaching of Islam is monotheism. But they interpreted divine unity in an unusually strict way, rejecting the existence of multiple attributes distinct from God. As for the idea that God is just, the Muʿtazilites again had a controversial interpretation of this uncontroversial claim. They believed that human reason can discern the nature of moral obligation. For instance, we perceive that it would be unjust—even for God—to punish people for deeds they cannot help committing. This led the Muʿtazilites to one of their signature doctrines: the affirmation of human freedom.

Other theologians objected to the Muʿtazilites’ confident application of human reason. For these opponents, we should base our beliefs on revelation alone. Some went so far as to accept that God has a body because the Qurʾān speaks of Him as having a face, or as sitting upon a throne. Naturally, the Muʿtazilites too saw revelation as an indispensable source for theology. Those who doubt their credentials as ‘philosophers’, preferring to reserve this term for thinkers who engaged with the Greek tradition, might point to the fact that the Muʿtazilites did argue on the basis of citations from the Qurʾān and ḥadıth (see further Box 2). But of course, the holy texts of Islam were common ground between all the theologians, except for disagreements about which ḥadıth should be accepted as reliable. In an effort to solve interpretive deadlocks, debates within kalām often had recourse to rational argumentation.

Box 2 The miḥna

In 833, the caliph al-Maʾmīn declared his support for a Muʿtazilite doctrine: the createdness of the Qurʾān. This teaching went together with the Muʿtazilite understanding of divine unity. The Qurʾān is the word of God, and thus can be seen as one of His attributes. To accept that this word is eternal rather than created would, according to the Muʿtazilites, make it a second divine entity alongside God Himself. That would violate the core Islamic principle of tawḥId (God’s oneness). Al-Maʾmīn and his successors, the very caliphs who sponsored the translation of Greek scientific works into Arabic, imposed an ‘inquisition’ or ‘test’ (miḥna) in which religious scholars and judges were required to accept that the Qurʾān was created. Some defied the caliphs and were persecuted, most famously Aḥmad ibn Ḥanbal. But in the end the attempt to enforce theological conformity failed. Ibn Ḥanbal was widely admired for his stance; one of the four orthodox legal schools of sunni Islam would come to be named for him. After the miḥna political rulers of sunni Islam would generally leave the theological debates to the scholars or ʿulamāʾ, a stark contrast to the top-down enforcement of orthodoxy we find in medieval Christendom. Perhaps for this reason, there has rarely been persecution aimed at philosophical beliefs in the Islamic world, even when those beliefs were markedly opposed to mainstream religious convictions. By contrast, sectarian religious beliefs have often been treated as politically seditious, with shiites persecuted by sunni rulers and vice-versa.

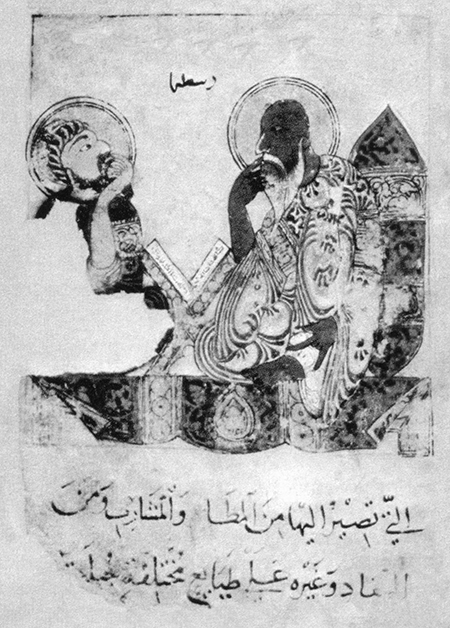

Another reason to begin our overview before the Greek-Arabic translation movement is that the movement did not occur in a vacuum. Already in late antiquity, Hellenic philosophy (see Figure 1) found its way into a Semitic language: not Arabic, but Syriac. In a foreshadowing of the ʿAbbāsid-sponsored Greek-Arabic translations, Christian scholars working at monasteries in Syria produced versions of works by Aristotle and other Greek thinkers. Some Christians, for instance Sergius of Rēshʿaynā (d. 536), composed their own philosophical treatises. This Christian scholarly tradition provided continuity between the Hellenic and Islamic cultures. When Islam spread through the Near East, Greek-speaking Christians fell within its sphere of influence. They retained their religious beliefs, and there continued to be scholars with facility in both Greek and Syriac. So when the ʿAbbāsid caliphs and other wealthy patrons of the 8th–10th centuries decided to have Greek scientific works rendered into Arabic, most of the translators they hired were Christians. This activity was centred in Iraq and particularly Baghdad, the new capital city founded by the early ʿAbbāsid caliph al-Manṣīr.

1. Aristotle teaching Alexander the Great, as pictured in a 13th-century Arabic manuscript.

One outstanding translation group was gathered around the Christian medical expert Ḥunayn ibn Isḥāq (d. 873). He specialized in translating the works of Galen, the greatest doctor of late antiquity. His son, the somewhat confusingly named Isḥāq ibn Ḥunayn (d. 910/11; ‘Ibn’ means ‘son’, so his name simply means ‘Isḥāq son of Ḥunayn’), concentrated on Aristotelian philosophy. Philosophy was also the focus of another group, the ‘Kindı circle’. Their leader was al-Kindı (d. after 870), the first faylasīf of Islam, that is, the first to engage with the newly translated Greek scientific and philosophical works. He does not seem to have known Greek himself, and he was a Muslim, yet he coordinated the efforts of a group of Christian translators. In addition to versions of treatises by Aristotle, the Kindı circle also produced Arabic translations of works by the two greatest late ancient Platonists, Plotinus (d. 270) and Proclus (d. 485). Probably due to a misunderstanding of prefatory comments that were added to the text in the Kindı circle, parts of the Arabic version of Plotinus were transmitted as the Theology of Aristotle. In other words, a major work of ancient Platonism was thought to be by Aristotle himself. A similar confusion attached to the Arabic Proclus. A version of the Kindı circle translation of Proclus’ Elements of Theology became known in Latin Christendom as the Book of Causes (Liber de Causis), also ascribed to Aristotle.

Al-Kindı was deeply influenced by these Neoplatonic sources, and by the genuine Aristotle, as well as a wide range of other translated sources. He was particularly interested in mathematical works by authors like Euclid and Ptolemy. He drew these ideas together in a series of treatises, often in the form of epistles addressed to his patrons, who included the ʿAbbāsid caliph al-Muʿtaṣim and the caliph’s son, whom al-Kindı tutored. These treatises set out to prove the agreement between Islam and Greek philosophy, in order to display the value of the newly translated materials for the educated elite of al-Kindı’s day. In his most important work, On First Philosophy, al-Kindı used Greek ideas to portray God’s unity in a way reminiscent of the Muʿtazilites, and to prove that the created universe is not eternal. But al-Kindı did not restrict his attention to theological questions. He wrote on a bewildering range of topics, from cosmology to ethics to the soul, to more practical topics like swords and perfumes. There are often connections between al-Kindı’s philosophy and his contributions in the applied disciplines. His epistles on cosmology provided an implicit rationale for other treatises on astrology, and his Pythagorean interests in mathematics played a role in several writings on music and even in a work on pharmacology.

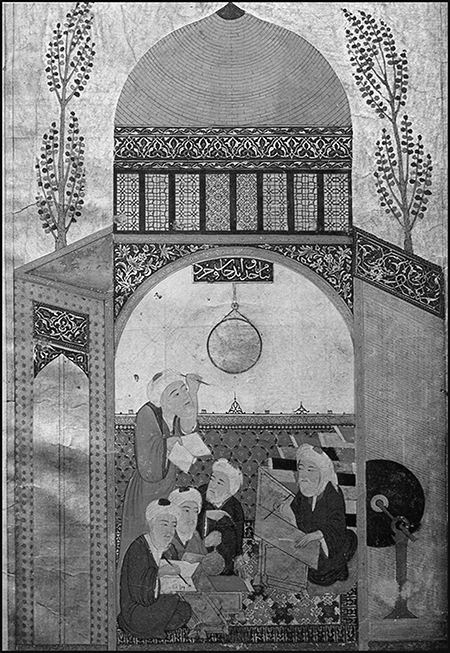

We can trace his influence among a number of thinkers who form a ‘Kindian tradition’. These figures, who included first-, second- and third-generation students of al-Kindı, followed his lead in seeing harmony between Islam and Greek philosophy, especially the Platonism they found in the Arabic versions of Plotinus and Proclus. The most important representatives of this tradition were al-ʿĀmirı (d. 991), author of (among other things) a reworking of the Arabic Proclus materials, and Miskawayh (d. 1030), who quoted al-Kindı at the end of his influential ethical treatise The Refinement of Character. Thinkers of the Kindian tradition, like al-Kindı himself, tended to be all-round intellectuals and not just philosophers. Throughout the formative period, philosophy was frequently pursued as just one among several cultivated arts among the intelligentsia (see Figure 2). Miskawayh, for instance, is well known for his work as a historian.

2. Portrait of the 10th-century Platonists known as the Brethren of Purity.

But philosophy also had its detractors. In a famous debate at the court of a Baghdad vizier, a Christian philosopher and exponent of the quintessential Hellenic discipline of logic, Abī Bishr Mattā (d. 940), was publicly embarrassed by a grammarian, al-Sırāfı (d. 979). Abī Bishr lost the battle, but not the war. Eventually logic would be widely adopted by Muslim theologians. In the shorter term, a group of Aristotelian philosophers associated with Abī Bishr would flourish for several generations. Mostly this group, the ‘Baghdad Peripatetics’, were Christians who devoted their attention to commenting on Aristotle, with forays into Trinitarian theology and Biblical exegesis. The most outstanding Christian member of the school was Yaḥyā ibn ʿAdı, from whom we have a number of philosophical and theological treatises. But a more famous name belongs to a Muslim connected to the group: al-Fārābı (d. 950). He shared his Christian colleagues’ interest in logic, and likewise wrote commentaries on Aristotle. His fame is, however, due more to his original systematic works, which integrate Aristotelian philosophy with themes from Neoplatonism. Against this cosmological and metaphysical setting, he set out an innovative political philosophy, influential on later thinkers like Averroes and Naṣır al-Dın al-Ṭīsı.

Jews as well as Christians played a major role in the philosophy of the formative period. We have a polite philosophical correspondence between Yaḥyā ibn ʿAdı and a Jewish philosopher, and al-Kindı’s writings were used extensively by one of the earliest Jewish thinkers in the Islamic world, Isaac Israeli (d. c.907). Jews also adopted ideas from the Islamic theology of their day. The chief example is Saadia Gaon (d. 942), a formidable scholar who wrote on Jewish law and Hebrew grammar, translated the Bible into Arabic, and composed a major philosophical-theological work, the Book of Doctrines and Beliefs. He has much in common with al-Kindı, for instance in his discussion of the eternity of the universe. But Saadia is most often compared to the Muʿtazilites, whose positions on human freedom and divine attributes he echoed and further developed.

Box 3 Al-RāzI vs the IsmāʿIlIs

The works translated in the KindI circle were popular among not just sunni Muslims, but also among shiites, and particularly the group of shiites called the IsmāʿIlIs. Shiite Muslims believe that legitimate rule over the Muslim community should have passed directly from the Prophet Muḥammad to his cousin and son-in-law ʿAlI, and then to ʿAlI’s line of male descendants—with different branches of shiite Muslims accepting different descendants as the legitimate leaders of the faith, or imams. Some IsmāʿIlI missionaries used Platonist concepts to explain the special insight granted to the imam. They were challenged by sunni Muslims, including a man with a very idiosyncratic approach to philosophy and religion: Abī Bakr al-RāzI (d. 925). One of the greatest doctors of Islam, al-RāzI developed his philosophy under the inspiration of the ancient medical writer Galen rather than Aristotle. His resulting theory of five ‘eternal principles’ was set out in works that are now lost, but we have reports about it from his greatest intellectual opponents, the IsmāʿIlIs. They portrayed him as an irreverent heretic, who denied the validity of all prophecy. He responded to one such critic by accusing the IsmāʿIlIs of slavish devotion to authority (taqlId).

Avicenna

In the wake of the translation movement, then, philosophy was developing in different ways among thinkers of various faiths. There was the hard-core Aristotelianism of the Baghdad school, the more irenic and broadminded stance of the Kindian tradition, anti-philosophical criticism from men like al-Sırāfı, and jostling for supremacy between Hellenic-inspired philosophy and Islamic kalām. But the situation would change in the 11th century, thanks to a thinker from the central Asian city of Bukhārā whose impact was unparalleled: Abī ʿAlı ibn Sınā, usually known in English by his Latinized name Avicenna (d. 1037). As we can see from a brief intellectual autobiography composed by Avicenna, he was a confident and largely self-taught genius who reserved the right to pass judgement on all his philosophical predecessors. In a series of works covering all the departments of philosophy, above all his magisterial Healing (al-Shifāʾ), Avicenna thoroughly reworked the ideas of the Aristotelian tradition as it had come down to him.

After Avicenna, philosophers had a stark choice: take Avicenna as the new starting-point, or try to undo the damage by retrieving the authentically Hellenic legacy. In the Eastern heartlands of Islam, the latter was attempted by ʿAbd al-Laṭıf al-Baghdādı (d. 1231), who despised Avicenna and tried to go back to Aristotle. But in these regions nearly everyone chose the former approach of engaging with Avicenna. Sometimes the engagement was highly critical, most famously in the case of al-Ghazālı (d. 1111), whose Incoherence of the Philosophers took aim at Avicenna rather than Aristotle. Over the longer term, theologians in the East would continue to criticize, but also selectively borrow from, Avicenna’s philosophy. The result was a long-lived tradition of kalām shot through with his distinctive terminology and distinctions. Out in the Muslim province of al-Andalus (modern-day Spain and Portugal), the situation was rather different.

Andalusia

Already the early Andalusian jurist Ibn Ḥazm (d. 1063) was able to study with a representative of the Aristotelian Baghdad school. This is the brand of philosophy that for the most part won out in Andalusia. Avicenna was much admired by Ibn Ṭufayl (d. 1185), author of the philosophical novel Ḥayy ibn Yaqẓān, in which the title character grows up alone on a desert island and becomes a self-taught philosopher. But even Ibn Ṭufayl complained of having poor access to Avicenna’s works. His predecessor, Ibn Bājja (Avempace, d. 1139), was much more influenced by Aristotle and by al-Fārābı, who exerted great influence on both Muslim and Jewish thinkers in Andalusia. Those who drew on al-Fārābı included the greatest Aristotelian exegete of the Islamic world: Ibn Rushd, like Avicenna usually known by a Latinized version of his name, Averroes (d. 1198). He produced numerous commentaries on the works of Aristotle in different formats. In them Averroes shows his mastery of both the Aristotelian texts and his commentators, from late antiquity to al-Fārābı and Ibn Bājja.

Averroes was not particularly influential among Muslim thinkers, for whom his revival of the Baghdad school’s Aristotle-centred philosophical project was no longer relevant. But in Latin Christendom, where the works of Aristotle were just attracting renewed interest in the 12th and 13th centuries, Averroes became the chief guide. Aristotle was called simply ‘the Philosopher’, and Averroes ‘the Commentator’. Averroes’ influence was perhaps even greater among Jewish readers in Andalusia and beyond: among readers of Hebrew it became common to consult Averroes’ commentaries and summaries of Aristotle rather than Aristotle himself. The great Jewish commentator Levi Ben Gerson (Gersonides, d. 1344) devoted his exegetical works to the exegeses of Averroes, producing ‘super-commentaries’ on the latter’s commentaries.

That was in the 14th century, by which point Jewish philosophy in Andalusia had been a going concern for quite some time. Already in the 11th century, we have Solomon ibn Gabirol (Avicebron, d. 1057/8) and his philosophical treatise The Fountain of Life (known often by its Latin title, Fons Vitae). This is not an overtly Jewish work, but rather a treatise drawing on Neoplatonic sources to articulate the relationship between God and created things. Ibn Gabirol also wove philosophical themes into his poems, which were a highpoint of Jewish literature in Andalusia. His Fountain of Life was written in Arabic, but the poems in Hebrew—setting an example for generations to follow, who often wrote philosophy in Arabic or Judeo-Arabic (written in Hebrew letters), whereas poetry and works on Jewish law or biblical commentary were typically in Hebrew. We see this in the greatest Jewish thinker of the medieval age, and arguably of all time: Maimonides (d. 1204), who wrote legal treatises in Hebrew but philosophy in Arabic.

When it came to philosophy, Maimonides adopted the Aristotelian project inherited from al-Fārābı, like his contemporary Averroes. He sought to reconcile this project with the Jewish tradition, clearing up apparent conflicts between the two in his famous Guide for the Perplexed. For some later Jewish thinkers, the Guide was unsettling in its rationalism and devotion to the Aristotelian tradition. Copies of the work were, infamously, burnt by Christian authorities in southern France in the 1230s. This occurred at the behest of Jewish conservatives who were alarmed by the rationalism of Maimonides and his supporters—for instance Samuel ibn Tibbon (d. 1230), who translated the Guide into Hebrew. The so-called ‘Maimonides controversy’ reflected the deep disagreement among Jews about the value of doing philosophy. But even the opponents of rationalist Maimonideanism acknowledged the authority of Maimonides himself when it came to questions of Jewish law.

The development of philosophy in Andalusia stands as the peak of Jewish thought in the medieval period, with Maimonides as the apex of that peak. This was possible because of the favourable conditions enjoyed by Jews in Muslim culture—a general feature of Islamic society throughout the medieval period, but particularly marked in Andalusia. Scholars frequently speak of the convivencia, the ‘living together’ of Jews, Muslims, and also Christians on the Iberian peninsula. This came to an end during Maimonides’ lifetime, with the invasion of the fundamentalist Almohads. Maimonides fled with his family and wound up living and working in Cairo, while other Jews relocated to Christian realms, including southern France. After the Christian ‘reconquest’ of Andalusia, the situation improved, but there was an appalling pogrom in 1391, when the Jews of Barcelona and elsewhere were massacred. One of the victims was the son of Ḥasdai Crescas (d. 1410/11), a brilliant philosopher and critic of Maimonidean Aristotelianism. Almost exactly a century later, the story of Muslim and Jewish thought in Andalusia would come to an end, when the last Jews and Muslims were exiled in 1492.

Box 4 Mysticism in Andalusia

For the subsequent history of philosophy in the Islamic world, the most influential thinker from Andalusia was Ibn ʿArabI (d. 1240), born in Mercia though he later relocated to Damascus. He drew together themes espoused by earlier figures, like the great female mystic Rābiʿa (d. 790s) and the provocative sufi martyr al-Ḥallāj (d. 922). For Ibn ʿArabI and other sufis, God lay beyond the grasp of human reason. Yet He shows Himself to us in the form of the universe He has created and in the revelation, especially the names He has given to Himself in the Qurʾān. Ibn ʿArabI set the stage for the later development of philosophical sufism, perpetuated in Andalusia by Ibn SabʿIn (d. 1270) and in Anatolia by al-QīnawI (d. 1274), who integrated Ibn ʿArabI’s ideas with Avicennan philosophy at the same time as al-QīnawI’s friend RīmI (d. 1273) was writing his famous mystical poems in the Persian language. Mysticism also blossomed among Jews in Andalusia, with the emergence of the Kabbalah, meaning ‘tradition’. Kabbalistic authors took inspiration from several late antique texts that adopted a symbolic approach to the divine—for instance by assigning numerical values to the limbs of God’s body. (A vivid contrast with the rationalism of Maimonides, who declared it the duty of all Jews to believe in God’s incorporeality!) One medieval text of the Kabbalah, the Zohar, in fact presents itself as a late antique work. Much as the sufis sought to grasp God insofar as possible through His names, the medieval Kabbalists spoke of ten sefirot (roughly, ‘numbers’) through which God shows Himself to His creation, while Himself remaining utterly transcendent.

Reactions to Avicenna

In the East, Avicenna supplanted Aristotle as the philosopher, but he attracted as many critics as admirers. Aside from al-Ghazālı, the most famous critic was Suhrawardı (d. 1191), founder of what he styled as a new ‘Illuminationist’ (ishrāqı) tradition of philosophy. Like sufis who were inspired by Ibn ʿArabı (see Figure 3 and Box 4), Suhrawardı wove together ideas from the philosophical tradition with mystical themes. But Suhrawardı’s taste was rather exotic when it came to his inspirations. In his greatest work, The Philosophy of Illumination (Ḥikmat al-Ishrāq), he claimed solidarity with ancient sages like Plato, for instance by affirming the reality of Platonic Forms. In fact Suhrawardı presented his Illuminationism as a recovery of the wisdom of several civilizations: Greek, Persian, and Indian. At the core of this Illuminationist philosophy, as the name suggests, was the concept of light. God, the ‘Light of lights’, creates by spreading forth rays of illumination that become progressively dimmer, with bodies constituting ‘dark’ obstacles to the divine splendour. All this was put forward in opposition to what Suhrwardı called the ‘Peripetatic’ philosophy, which for him meant Avicennism, not Aristotelianism.

Alongside Suhrawardı and a few thinkers in the subsequent generations who commented on his works (especially al-Shahrazīrı, d. after 1288), another line of response to Avicenna developed within the Ashʿarite school of kalām. This school’s founder, al-Ashʿarı (d. 935/36), began as an adherent of the Muʿtazilite doctrines but came to reject them. Against the Muʿtazilites’ austere conception of divine unity, the Ashʿarites accepted the distinct reality of God’s attributes. They also believed that the Muʿtazilite stance on human freedom was insufficient to safeguard God’s omnipotence, and insisted that God creates absolutely everything other than Himself, including human actions. If the core of Muʿtazilism was its faith in the power of human reason, the core of Ashʿarism was respect for God’s untrammelled power and freedom to do as He sees fit. Even moral obligations, from their point of view, arise only once God has laid them upon His creatures. Hence the Ashʿarites endorsed a ‘divine command’ theory of morality, whereas the Muʿtazilites thought that even God must adhere to certain moral principles.

3. The tomb of Ibn ʿArabi in Syria.

Though Muʿtazilism did live on in the post-formative period, the Ashʿarites (and a similar school, the Māturıdıs) became the dominant force in sunni theology. Avicenna seems to have been influenced by Ashʿarism to some extent, though to what extent is a matter of debate. There’s no debating the influence in the other direction, as Ashʿarite theology absorbed Avicenna’s thought. Even the assault on Avicenna in al-Ghazālı’s Incoherence falls short of a thorough rejection. After all, he refutes only certain Avicennan theses, implying that the others may be acceptable. (A similar range of Avicennan theses was targeted slightly later by another Ashʿarite, al-Shahrastānı (d. 1153).) Furthermore, al-Ghazālı insists on the value of disciplines like logic and astronomy, dismissing critics of the latter by quoting the proverb, ‘a rational foe is better than an ignorant friend’. So it was arguably in part thanks to, rather than in spite of, al-Ghazālı that Avicennan philosophy and especially Avicennan logic became abiding interests of later Ashʿarites.

A particularly outstanding representative of philosophical Ashʿarism was Fakhr al-Dın al-Rāzı (d. 1210), who is not to be confused with the above-mentioned Abī Bakr al-Rāzı (the name ‘al-Rāzı’ just means someone from the Persian city of Rayy). Fakhr al-Dın wrote lengthy and complex treatises covering many of the main topics raised by Avicenna’s philosophy, enumerating arguments for and against a range of possible views on each topic. Fakhr al-Dın was an appreciative exegete of Avicenna as well as a critic. Evidence for this is his detailed, though often critical, commentary on Avicenna’s late work Pointers and Reminders (al-Ishārāt wa-l-tanbıhāt). This commentary provoked a backlash from the greatest Avicennan of the 13th century, Naṣır al-Dın al-Ṭīsı, who wrote a counter-commentary on the Pointers that is far more approving of Avicenna’s arguments. Yet al-Ṭīsı was not just a commentator, a kind of second Averroes devoted to Avicenna rather than Aristotle. To the contrary, he was a protean thinker, who at different stages of his career espoused two varieties of shiite Islam, and who could sound either mystical or highly rationalist depending on context.

Furthermore, al-Ṭīsı made great contributions in the sciences, especially astronomy. He was the head of a group of philosophers and scholars at an astronomical observatory sited at Marāgha in modern-day Azerbaijan (see Figure 4). This group’s members were remarkably varied in philosophical approach, though all had an interest in some core disciplines like logic and of course astronomy. They included a major Illuminationist thinker, Quṭb al-Dın al-Shırāzı (d. 1311), an Avicennan theologian named al-Kātibı (d. 1276), who rethought Avicenna’s logic in one of the most widely read logical textbooks of all time, al-Risāla al-Shamsiyya, and even a Christian philosopher, Bar Hebraeus (d. 1286). To complete the ecumenical picture, we can add that al-Ṭīsı exchanged philosophical views with Ibn Kammīna, a Jewish thinker who took an interest in Suhrawardı’s Illuminationist philosophy. Nor was Ibn Kammīna the first Jewish author involved in this long-running engagement with Avicenna. Earlier, a Jewish-Muslim convert named Abī l-Barākāt al-Baghdādı (d. 1160s) had written the Book of What Has Been Carefully Considered (Kitāb al-Muʿtabar). As the title suggests, Abī l-Barākāt was passing judgement on previous philosophers, including Avicenna, in much the way that Avicenna had passed judgement on the Aristotelian tradition. In the process, Abī l-Barākāt made some proposals on topics in physics not unlike those of the aforementioned (but chronologically later) Western Jewish critic of Maimonides, Ḥasdai Crescas.

4. A 15th-century Persian manuscript of Naṣır al-Dın al-Ṭīsı’s observatory at Maragha depicting astronomers at work teaching astronomy, including how to use an astrolabe. The instrument hangs on the observatory’s wall.

The Mongol period

With al-Ṭīsı’s group at the Marāgha observatory, we already reach the time of the Mongol invasions, which spread death, destruction, and disruption across the Eastern Islamic lands. Surprisingly, philosophy and scientific activity were able to survive and even find sponsorship under the Mongols. The Marāgha observatory enjoyed the patronage of Hülegü, the Mongol conqueror of Baghdad (according to legend, al-Ṭīsı advised him on how to execute the last ʿAbbāsid caliph). A later ruler of Mongol descent, Ulegh Beg, sponsored another observatory at Samarqand. The royal court of Samarqand could also boast of significant intellectuals, for instance the theologian al-Taftazānı (d. 1390). He and earlier Mongol-era sunni theologians like al-Ijı (d. 1355) produced comprehensive summaries of the philosophically tinged sunni kalām pioneered in the previous couple of centuries. These duly became the object of further commentaries, and were studied by many generations of young religious scholars in madrasas across the Islamic world. In fact works by theologians, together with standard commentaries, were still being studied at al-Azhar university in Cairo in the 20th century, as were logical treatises like the aforementioned Risāla al-Shamsiyya of al-Kātibı. In the formative period intellectuals like al-Kindı and al-Fārābı expected philosophy to supplant kalām, using the tools of Hellenic wisdom to provide superior answers to questions raised by the Islamic revelation. In the end, something very different happened. Kalām became a vehicle for the spread of philosophy, albeit that the philosophy in question derived from Avicenna rather than Aristotle or Plotinus.

These developments were remarked upon by some of the sharper observers of the time. No observer was sharper than the historian Ibn Khaldīn (d. 1406), who had the luxury of witnessing the Mongol invasion from a safe distance, since he came from the Western Islamic world (the ‘maghreb’). He noted that Hellenic philosophy had been replaced by something new—‘as if the books of the ancients had never been’—and that kalām and philosophy had become effectively indistinguishable. Ibn Khaldīn himself stood outside of that tradition. Neither an Avicennan nor a mutakallim, he innovatively applied the empirical lessons of Aristotelian science to the subject of human history. Looking back over the rise of Islam and the success of tribal groups like the Almohads in Andalusia, Ibn Khaldīn came to a general theory about the rise and fall of political dynasties.

Similar observations about fusion of philosophy with kalām had already been made earlier, with no little alarm, by Ibn Taymiyya (d. 1328). He promoted a radical approach to jurisprudence (see Box 5), which rejected centuries’ worth of legal orthodoxy in favour of what he perceived as the teachings of the first Muslim generations. Ibn Taymiyya also railed against the various corruptions he perceived in Muslim intellectual life. Unlike the earlier critic of philosophy al-Ghazālı, Ibn Taymiyya had nothing but scorn for the discipline of logic. He wrote at length about its uselessness, remarking that expertise in logic is like camel meat on a mountain top: hard to reach, and not worth much once you’ve got it. Nor was he impressed by ‘philosophical sufis’ (his phrase), who to his mind represented as grave a threat to Islam as the Mongol hordes.

Box 5 The Islamic legal schools

There is a long history of mutual interaction between law and philosophy in the Islamic world. It was common for both Jewish and Muslim philosophers to be legal scholars: al-GhazālI, Averroes, and Maimonides are only the most famous examples. Within Islam, there are four orthodox legal madhhabs or schools in sunni Islam, each named after an esteemed religious authority: the ḤanafIs, the ḤanbalIs, the ShāfIʿIs, and the MālikIs. They largely agreed on broad methodological issues, but were distinguished by areas of geographical dominance (for instance the MālikIs were the main school in the West) and on many points of legal detail. In addition the shiite Muslims had their own legal tradition. Within sunni Islam there were other, less influential approaches to law. For instance the Andalusian jurist Ibn Ḥazm was a ẒāhirI, meaning that he followed only the ‘evident (ẓāhir)’ meaning of pronouncements in the Qurʾān and ḥadIth, without drawing analogies or inferences as did the jurists of the orthodox schools.

Three empires

By the beginning of the 16th century, the chaos caused by the Mongols was fading into memory and new political realities were settling in. Three powerful empires controlled most of the Islamic world (see Map 3). The earliest to rise to dominance were the Ottomans, who managed to take Constantinople from the Byzantines in 1453. Somewhat later, in India, rulers with Mongol blood-lines founded the Mughal dynasty. Under both Ottomans and Mughals, philosophy continued along more or less the lines we have seen in the Mongol period. The ‘intellectual sciences’ were practised in both empires. Sophisticated astronomical work was done in the Ottoman realm by figures like ʿAlāʾ al-Dın al-Qīshjı (d. 1474). In Mughal India, a standard curriculum developed for the study of philosophical kalām, the so-called dars-i niẓāmı, named for Niẓām al-Dın Sihālavı (d. 1748), a scholar who helped determine which works should be studied. He was a member of a family of scholars, the Farangı Maḥall, who emerged in Lucknow in the 18th century. In the 19th century another family, the Khayrabādıs, would carry on the practice of study and commentary on the classical works of Avicennizing kalām

A similar programme of study was followed under the Ottomans, though Kātib Çelebi (d. 1657) worried that the intellectual sciences were stagnating in his day. Philosophical kalām had competition from other intellectual currents. For the moderate Çelebi, one worry was a populist religious movement, the Kādızādelis, strong critics of corruption among the scholarly class or ʿulamāʾ. Like Ibn Taymiyya before them, the Kādızādelis also took aim at the excesses of sufis. But philosophical sufism continued to thrive in the face of such criticisms. In India, a Mughal prince named Dārā Shikīh (d. 1659) even wrote about the harmony between sufism and the teachings of classical India. A later mystical philosopher of India, Shāh Walı Allāh (d. 1762), was also convinced that multiple religions could represent versions of the single eternal truth. Through it all, the madrasas of both empires continued to teach students logic, and theologians continued to debate the merits of Avicennan philosophy. Earlier in the Ottoman empire, a sultan even asked two scholars to offer competing assessments of al-Ghazālı’s criticism of Avicenna in the Incoherence of the Philosophers.

All of which should make it clear that philosophy and science did not, as is so often supposed, vanish in the Islamic world after the medieval period. And we haven’t even mentioned the best known of the later philosophical traditions, which unfolded in Persia. In the early 16th century, the area corresponding to modern-day Iran fell under the sway of the shiite Safavid dynasty. Just before and during the rise of the Safavids, three significant thinkers emerged in the Persian city of Shırāz: Jalāl al-Dın al-Dawānı (d. 1501), Ṣadr al-Dın al-Dashtakı (d. 1498), and the latter’s son Ghiyāth al-Dın al-Dashtakı (d. 1541). A hostile rivalry between the two Dashtakıs and Dawānı was fought out over questions of logic, metaphysics, and the interpretation of Avicenna. Their mutual refutations, often presented in commentaries or glosses on earlier thinkers, would themselves be made the object of many commentaries in the coming centuries (see Figure 5).

But the greatest thinker of early modern Iran is universally acknowledged to be Mullā Ṣadrā (d. 1640). He typified the syncretic tendencies of philosophy under the Safavids. Like the earlier Ismāʿılı thinkers (see Box 3), Safavid philosophers found Hellenic Platonism to be a good fit with shiite theology, and Greek-Arabic philosophical translations were thus read with the sort of careful attention they had rarely received since Avicenna. We even find commentaries being written on the Arabic Plotinus, or Theology of Aristotle, at this time. Alongside these Hellenic ideas, Ṣadrā drew on materials from Avicenna, Avicennan kalām, and philosophical sufism. Yet he was also a startlingly original thinker, whose theory of ‘modulation’ in being and substantial change promised to resolve long-standing disputes about existence and the nature of God.

5. Manuscript image showing how glosses were added to comment on philosophical texts.

The modern age

Ṣadrā’s theories have also met with opposition in some quarters, and though he was always read he became the central inspiration for Iranian philosophy only from the 19th century onwards. This was in part thanks to sympathetic exegesis by Sabzawārı (d. 1878) and more recently ʿAllāmah Ṭabāṭabāʾı (d. 1981). Seyyed Hossein Nasr (born 1933), originally from Iran but now an academic based in the United States, has been inspired by Ṣadrā and also by Ṭabāṭabāʾı; the two read philosophy together in Iran. Nasr has also urged a broad, multi-faith and multi-cultural perspective that finds commonalities in many traditions within and beyond the borders of Islam. Taking a page from the book of Shāh Walı Allāh, Nasr sees fundamental agreement between a number of religious traditions on a core set of commitments he calls the ‘perennial philosophy’. He has even suggested that these shared values could provide an effective basis for environmentalism, since the perennial philosophy urges the subordination of selfish desire to the good of the whole creation.

While Ṣadrā and other figures from Islamic history have provided inspiration for latter-day intellectuals, philosophical and scientific ideas from beyond the Islamic world have also had an impact. In the 18th century, Ottoman thinkers like the philosophical sufi ʿAbd al-Ghanı al-Nābulusı (d. 1731) were already arguing for a ‘renewal’ of Islam that would respond positively to European science. By the 19th century, the Ottoman sultans were looking to European models as they brought in bureaucratic, military, and educational reforms. This helped launch more radical reform movements, the Young Ottomans and Young Turks, who made frequent mention of European philosophy in formulating their political views. Two leading Young Turks, Ziya Gökalp (d. 1924) and Abdullah Cevdet (d. 1932), drew respectively on the sociology of Émile Durkheim and the theories of Ludwig Büchner and Auguste Comte.

The same point is illustrated by the greatest Muslim political philosopher of the early 20th century, Muḥammad Iqbāl (d. 1938). Iqbāl’s political activities in his native India were inspired by the education he received in Europe, and by ideas taken from Friedrich Nietzsche. Islamic intellectual history has in a sense come full circle. Ideas from European philosophers from Descartes to Heidegger have provoked reactions similar to those that greeted the medieval Greek–Arabic translation movement: outright opposition in some quarters, enthusiastic embrace in others, but most often a circumspect approach of reinterpretation and rethinking in light of the Islamic revelation.