Chapter 7

Monitoring your Progress and Responding to Change

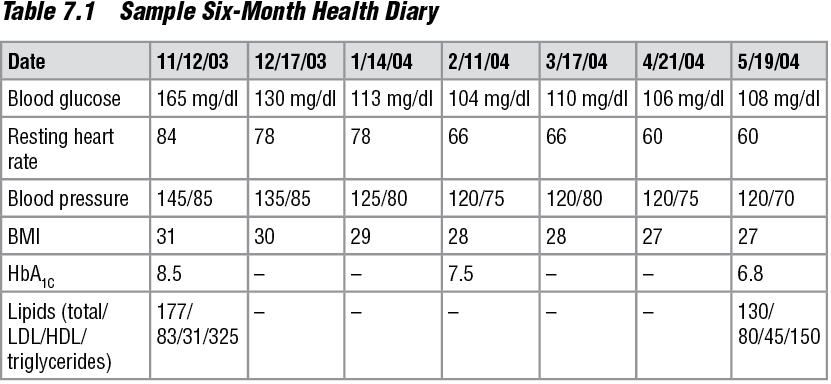

In this chapter I discuss how to monitor your progress after you have put your action plan for diabetes into motion. As you monitor your progress, you will need to document the changes in your health status in a personalized health diary. This diary should include information such as the dates and times of blood glucose levels associated with exercise and diet. You should also include your heart rate, blood pressure, weight or body mass index (BMI), any symptoms and laboratory values such as your hemoglobin A1C levels and lipid levels, and any other tests that you have undergone. I have found that some of my patients who keep health diaries like to bring them to their appointments to show me the patterns in their health and to record their laboratory test results.

As discussed in previous chapters, it is important for you to recognize the differences between type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes and to make regular exercise a part of your lifestyle. People with both types of diabetes benefit from exercise. The main concern for those with both types of diabetes is to monitor blood glucose levels. Those with type 1 diabetes need to monitor glucose closely when exercising, especially when starting an exercise program. Hypoglycemia, or low blood sugar, is the prime risk associated with exercise for those with type 1 diabetes. Hyperglycemia during exercise is also a serious concern in those with type 1 diabetes. People with type 2 diabetes have a very low risk of hypoglycemia unless they are taking sulfonylureas or other medications that are associated with causing hypoglycemia. Those with type 2 diabetes need to ensure that their glucose is not too high when starting their exercise program, and they need to monitor their glucose level to gauge the effectiveness of their diet and exercise. If you do not have a clear understanding of this, review chapter 4.

As you progress through your plan and become more active, you may choose to keep track of how your fitness level improves. Your health care team will track your cholesterol and blood pressure periodically. If you are using exercise and diet alone to optimize your cholesterol levels, it is generally recommended that these levels be tested every six months. If you use medication to control your cholesterol levels, your physician may choose to test your lipid levels more frequently. Your blood pressure can be tested at each visit, and you can check your own blood pressure at home twice a week by using a calibrated blood pressure cuff and meter. You can purchase a blood pressure cuff and meter at your local drug store or online. You will pay $15 to $100 for a simple cuff and meter; accuracy and durability typically increase with the cost of the unit. For $50 to $600, you can get other, more sophisticated automatic digital models that measure your heart rate and are more clinically accurate. (To determine the accuracy of your home blood pressure monitor, take your blood pressure cuff to your doctor’s appointment and compare readings from the doctor’s meter and your meter.) The key is to measure blood pressure at the same time each day after you have been sitting for at least five minutes. You should document these levels in your health diary so that you can determine your progress in your action plan. See table 7.1 for an example of a filled-in six-month health diary, and table 7.2 for a blank health diary you can use.

If you have type 2 diabetes, a diary can help you keep track of how your lifestyle affects your glucose control. A complete diary that includes your weight or BMI, descriptions of meals, exercise intensities and durations, glucose levels, and other laboratory values can function as an efficient gauge to tell how well you are doing with your action plan. You can also use a diary as a motivation tool, especially once you see the effects of your action plan on your condition. For example, Tom, a gentleman of about 55 years old whom I help with his medical care, has found his health diary to be very motivational. In addition to type 2 diabetes, Tom has multiple sclerosis (MS), a disease that results in easy fatigability and other symptoms that can make exercising difficult. When I first met Tom, he was skeptical about creating a diet and exercise plan because of the complications of MS. He had tried exercising before but found that he overheated and fatigued easily. He’d met with a dietitian in the past but had not seen significant positive results. After discussing with me the basics of diabetes and the differences between exercising to improve health and exercising to significantly increasing fitness level, he felt more at ease about creating an action plan. Once he realized that I was not going to ask him to do what he already knew he couldn’t do, we started him on his plan. His plan included riding his bike for 10 to 15 minutes (this varied depending on how he felt on any particular day) and walking in the mall for 10 to 20 minutes on other days. He knew that he could not do these things for too long if he started to notice problems such as overheating. And we designed his action plan around this concern, allowing for daily flexibility. About six weeks after starting his program, he returned to my office, and we reviewed his diary. As I expected, he had some exercise sessions lasting 20 minutes, some that were split into smaller, more tolerable sessions, and no sessions on some days. But Tom met his minimum weekly goal of exercise. We made some adjustments to his plan, and then I saw him about two months later after doing some scheduled laboratory tests. He was very excited to find that he’d normalized his fasting blood glucose and lowered his HbA1C from 8.5 to 7.5. From the expression on his face I could see that he was no longer skeptical about his action plan. Three months later, he had mastered his action plan and normalized his HbA1C, LDL, and HDL; significantly decreased his triglycerides; and lost 8 pounds. I met with Tom not long ago and he has had to make adjustments to his schedule because of work issues, but he’s confident that he can adjust without a glitch.

Monitoring Your Glucose

Before beginning any type of exercise program, you should be well acquainted with the glucose meter you and your health care team have chosen to use. You also need to maintain the quality of your testing unit. Accuracy in glucose monitoring is important when gauging the effectiveness of exercise on your health. The best way to ensure this is to have a member of your health care team, typically the diabetes nurse educator, teach or review the proper techniques for testing your blood and maintaining your glucose meter. Most blood sugar monitors work the same way: After you insert a plastic strip or disk into the glucose meter, you obtain a small drop of blood by pricking your finger, palm, or arm with a spring-loaded pen that contains a lancet. Then you put the drop of blood on the plastic strip or disk, and in less than a minute the glucose meter gives you a digital reading of your blood glucose level.

Keeping track of the exercise you do and comparing it with the results of your glucose tests will help you determine what is working and what isn’t.

Noninvasive Blood Glucose Monitors

The FDA has recently approved the use of noninvasive blood glucose monitors. One of these devices, which looks like a wristwatch, checks blood glucose levels without puncturing the skin for a blood sample. It can provide six measurements per hour for 13 hours. However, this device is not meant to replace traditional glucose testing; it’s used to obtain additional glucose readings between traditional blood tests. The monitor requires daily calibration with the use of standard finger-stick glucose measurements.

The following are some other methods of glucose monitoring that are currently being tested:

• Shining a beam of light on the skin or through body tissues

• Measuring the energy waves (infrared radiation) emitted by the body

• Applying radio waves to the fingertips

• Using ultrasound

• Checking the thickness (also called viscosity) of fluids in tissue underneath the skin

Choosing a Glucose Meter

Many varieties of blood glucose meters are available, each with various features that can make testing your blood sugar fairly easy. You can ask your doctor or diabetes nurse educator to help you determine the best monitor for you. You can also do an Internet search on blood glucose monitors to find unbiased consumer ratings on various models. These ratings are based on ease of use, amount of blood required for testing, cost, speed of results, and variety of features.

Most electronic glucose meters automatically log blood glucose levels; some store as few as 40 readings, and others can store over 3,000 readings. Most monitors are equipped with computer interface ports that allow users to upload blood sugar readings, as well as the date and time of each reading, into a personal computer with the use of special software. Many physicians use this software in their offices, enabling patients to forgo paper-and-pen methods of record keeping of blood glucose levels. Some more sophisticated glucose meters allow you to record your activity levels, dosages of insulin, food intake, and any other data that you and your physician may think are important in monitoring your health. Meters with these electronic record-keeping features are convenient for those who travel frequently and don’t want to pack log books into their luggage.

If you have Medicare insurance coverage, you can get 100 percent reimbursement for blood glucose monitors and test strips, and it doesn’t matter which meter you choose, be it a simple, inexpensive device or a more expensive, more sophisticated model. If you have HMO coverage or private insurance coverage, you may be able to get your blood glucose monitor at no cost, but often there’s a copayment or deductible charge for test strips. Insurance companies offer reimbursement or low costs for blood glucose monitors because monitors are a reliable preventive measure against long-term complications. Patients who regularly use blood glucose monitors end up saving insurance companies money in the long run because patients can control their health and avoid emergency room visits, hospitalizations, and other drug expenses simply by controlling their blood sugar levels.

Whatever form of documentation you choose to use (pen and paper or your monitor’s memory features), this documentation allows you and your health care team to spot patterns and make correlations between your diet and exercise plans. For instance, if you have type 1 diabetes and are on a mixed-insulin regimen and note that your afternoon glucose reading is low on the days when you exercise in the morning, you and your physician may choose to increase your food intake or change the morning dose of your longer-acting insulin according to your activity level on those days.

Determining When to Check Your Blood Glucose

You need to know when you should monitor your blood sugar levels and what your glucose range should be. You and your health care team should determine this. It is generally recommended that you test your blood sugar just before you exercise, every 30 minutes during exercise, and 15 minutes after exercise. To prevent delayed-onset hypoglycemia, which typically occurs in the early stages of your exercise program or when the intensity of your activity increases, you should measure your glucose levels 6, 12, and 24 hours after cessation of exercise until your program has stabilized.

As a general guideline once your plan has stabilized, make sure that before exercising your glucose is at or slightly above 100 mg/dl. If your glucose is below 100 mg/dl, you should eat or drink something with carbohydrate in it until your blood glucose is in this range. The goal is to avoid hypoglycemia. If your glucose is at or above 100 mg/dl, then you need to take into account the effect that insulin or another glucose-lowering agent and exercise will have on your blood glucose, as discussed in detail in chapter 4. For instance, if you take insulin or have it in your system just before you exercise and you have not eaten, you are likely to experience a significant drop in your glucose level. Furthermore, it is generally accepted that exercise should be postponed if the glucose is more than 250 mg/dl and ketones are present in the urine, or if your glucose is greater than 300 mg/dl. (You can measure the urine ketone levels with urine test strips, which are available at your local pharmacy.) The American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM) guidelines state that if your glucose is between 200 and 400 mg/dl, you should consult your physician before exercising. If your glucose is greater than 400 mg/dl, the ACSM suggests that you do not exercise.

Glucose Too High to Exercise?

If your glucose is between 200 and 400 mg/dl, then you need medical supervision during exercise.

If your glucose is over 400 mg/dl, then seek medical attention and do not exercise.

Charting Weight Loss

In addition to glucose monitoring, weight control is important for those with type 2 diabetes. Charting your weight loss in your health diary can prove to be very rewarding. And this may be an interesting analysis of how exercise and diet can help you realize the positive changes described in this book. For instance, when comparing your weight against your average glucose over a three-month period, you are likely to see that your weight will decrease along with your average glucose level. You can compare your weight or glucose level to your heart rate, blood pressure, or laboratory values such as the hemoglobin A1C as well. You can create charts similar to those in tables 7.1 and 7.2 to compare values.

The amount of weight you lose depends on your energy balance, as described in chapter 5. You and your health care team will develop a diet and exercise plan that you can incorporate into your lifestyle that will most likely allow you to lose an average of .5 to 2 pounds a week. As with most situations regarding your health, this will depend on your current activity level, physical abilities, and any other medical conditions. Furthermore, you are more likely to maintain long-term weight loss if you lose weight in smaller amounts over a longer time as opposed to losing large amounts of weight over a short time. It is widely known that a dramatic weight loss in a short duration is largely due to body fluid loss and not to fat loss.

A good time to weigh yourself is in the morning, before you eat. Measuring your weight in this manner will give you more consistent results and less appearance of fluctuation in your weight over time. You should measure your weight a maximum of twice per week.

The key to weight loss is energy balance: The number of calories you burn must exceed the number of calories you take in.

Responding to Change

When you start to see positive changes in your health, such as a decrease your weight or better control of your glucose, make sure that you document this in your health diary. The more pertinent information that you can record in an organized fashion in your diary (without obviously overdoing it), the easier it will be for you to find and capitalize on the key components that have allowed you some success. For example, if you have type 1 diabetes or type 2 diabetes requiring insulin, you may discover from your records that, on mornings when you exercise after taking your insulin, your glucose after breakfast is low. With this information you and your doctor can make the decision to decrease your rapid-acting insulin morning dose, change your exercising time, or change your meals.

If you have type 2 diabetes, you may find that your BMI has been decreasing, but you still have not achieved good glucose control. In this case you and your physician or dietitian may decide to analyze and make changes to the types of foods that you have been eating that may contribute to the elevated glucose levels. Or perhaps your physician will add glucose-lowering medication to your plan.

If you encounter a change in your health that would be considered negative, such as difficulty losing weight or symptoms of hypoglycemia or little or no change in weight, lipids, glucose levels, or blood pressure, document these results in your diary as well. In some cases it may be even more important to document the negative changes in comparison to the positive changes because some of these can pose a serious threat to your health.

If you find that you are not making progress in your action plan, it will be easier for you and your health care team to find solutions to the problems if your plan is well documented. For instance, you may find yourself gaining weight instead of losing weight while adhering to your action plan. This can be frustrating and may even cause you to quit your plan. Fortunately in most such cases, the problem and its solution lie within the realm of energy balance. It may be a simple miscalculation of the total number of calories you consume and the amount of exercise you need to burn those calories and create an energy deficit to stimulate weight loss. This is an easy problem to fix if you have detailed documentation of the intensity, duration, and type of exercise you are doing, along with the food log to allow you and your dietitian to redo the calculations to make your plan work for you. Sometimes the problem may be more difficult than this, but finding the solution will still be far easier if you have monitored and documented the details of what you have been doing in your action plan for diabetes.

You should note that you may not see a change in your weight for a couple weeks. Give your body some time to adjust the new activity and caloric intake. If you continue to have a problem despite recalculating your energy balance, visit your health care team for more specific guidance.

Action Plan:

Monitoring Progress and Responding to Change

• Start a health diary in a notebook, on your computer, or in another format that’s convenient for you.

• Learn how to check your blood pressure at home.

• Make sure you are well-versed in how your particular method of glucose monitoring works, and know the best times to check and record glucose, especially with regard to exercise.

• Come up with a plan for keeping track of your weight. Perhaps devise a table in your health diary where you keep track of what you eat every day.

• Be aware of the changes that are happening in your body—both positive and negative—and have a plan for how you’ll respond.