Chapter 8

Taking Medications and Supplements

Throughout this book I have stressed the importance of understanding how diabetes affects you and how you can affect diabetes through exercise and healthy eating habits. In addition to prescribing exercise and a healthy diet, your doctor may add medications to your plan to optimize your glucose control. In this chapter we take a look at medications that can help you control your glucose levels and how exercise and diet may interact with those medications. In addition, we discuss the use of other medications and supplements that you may encounter and their potential effects on your health.

Drug Treatment of Type 1 Diabetes

People with type 1 diabetes use insulin to control their diabetes, and most use injections just underneath the skin (either via a hypodermic needle attached to a manual syringe or via an automatic delivery pump). Many with type 1 diabetes take a mixture of two types of insulin in the same injection. Typically one of the insulins has a rapid onset of action and a relatively short duration; the other insulin has a slower onset of action and a longer duration. This is referred to as a mixed dose. The most common form of rapid-acting, or short-acting, insulin is known as regular insulin. Another common short-acting insulin is called lispro (brand name is Humalog). Lispro is absorbed more rapidly than regular insulin, and it has a shorter duration. The most common longer-acting, or basal, insulin is called NPH insulin. Other types of longer-acting insulins may be used as well, such as lente, ultralente, and insulin glargine, which have very long durations of action and lower peak levels. Determining your correct insulin regimen can often be a process of trial and error. Your doctor will work with you and the other members of your health care team to determine the correct combinations and dosages of insulin for you.

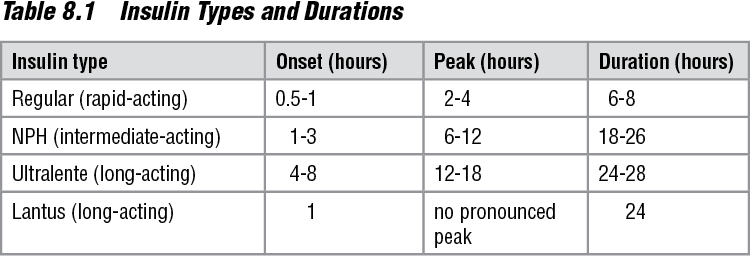

As described previously, if you have type 1 diabetes you need to avoid hypoglycemia; you can accomplish this by taking great care to ensure that your carbohydrate and total caloric intake is coordinated with your insulin regimen. If you have type 1 diabetes and are exercising, it is even more important that your food intake and insulin dose correspond to the timing and amount of exercise you are doing. It is generally recommended that you do not exercise if your insulin’s action is at or near its peak. It is best to exercise when your insulin’s activity is low and your glucose levels are rising or higher than they are near the peak of your insulin’s effectiveness. (See table 8.1.)

Monitoring your glucose regularly is critical to finding overall balance. Monitors have made individualized insulin modification simpler for patients and physicians. It is important to remember that each person’s response will vary depending on the severity of the disease, exercise choice, and fitness level. A good starting point is decreasing the dose of short-acting insulin (regular or lispro) by 30 to 50 percent two to three hours before starting exercise. Those with an insulin pump may choose to decrease or eliminate the basal infusion of insulin during exercise. Many people with diabetes inject 1 to 3 units of regular or lispro insulin before exercise when their preexercise glucose levels are between 250 and 300 mg/dl (Colberg and Swain 2000). Keep in mind that hyperglycemia can cause dehydration; therefore, you should also monitor your hydration status.

If you have a significant amount of exercise or physical activity that is unplanned, be sure that you have some form of carbohydrate readily available to consume so that your blood glucose does not drop significantly and cause symptoms of hypoglycemia. You can typically prevent this by eating a snack before or during exercise.

The best way to avoid hypoglycemia is to discuss your specific exercise and diet plans with your health care team. Let your physician know about any changes you want to make in your diet and exercise plans so that he will be able to help you make adjustments to your insulin regimen that will help prevent hypoglycemia and control your glucose.

As discussed in chapter 7, it will also be beneficial for you to keep a detailed log of your insulin dose, food intake, and exercise intensity and duration while creating your action plan. Once your exercise routine and diet plan are stable, you can relax a little in your record keeping, but you still need to be aware of potential situations that can lead to hypoglycemia. You need to avoid hyperglycemia as well. You will typically run into this problem only if your insulin dose, caloric intake, and physical activity are not balanced.

Drugs on the Horizon

A new preparation of insulin is currently being tested that may allow insulin to be taken via an inhalation device such as those used by people with asthma. If these new delivery systems can consistently treat people with diabetes with the same or better safety and efficacy as insulin injections provide, then the advantage is clear—no more needle sticks from taking injections or disposing of needles. However, the disadvantages with this type of system are not as clear. For instance, how easy will it be to switch from your current injectable insulin to the inhaled form? Are there any long-term side effects from using inhaled insulin? Does exercise change the absorption rate of inhaled insulin? All these questions and many more have yet to be answered.

Drug Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes

If you have type 2 diabetes and are having a difficult time controlling your glucose with diet and exercise alone, your physician may decide to add a medication that will either increase your sensitivity to insulin, increase your production of insulin, or decrease the absorption of glucose from your gastrointestinal tract.

As discussed in chapter 1, people with type 2 diabetes typically have a decreased sensitivity to insulin. In other words, the insulin that is present in the body is not very effective at allowing glucose from the blood to pass into the cell. Medications that increase the sensitivity of the body’s cells to insulin allow glucose to be used for energy by the cell by decreasing the level of blood glucose. Several forms of this medication, such as those referred to as biguanides, have a direct effect in the liver; other medications, commonly referred to as glitazones, have an effect predominantly in other tissues.

When glucose is high in the blood as a result of the cells’ decreased sensitivity to insulin and the environment inside of each cell is low in glucose, the cells, particularly those in the liver, will begin a process called gluconeogenesis, which means a new generation of glucose. So even though the glucose is high in the blood, when the liver is insensitive to insulin it produces more glucose, which increases the glucose in the blood to an even higher level. The biguanides (Glucophage is a common brand name) increase the cells’ sensitivity to insulin, thus allowing glucose to flow freely into the cell, which in turn decreases the glucose production in the liver. The glitazones (brand names Avandia and Actose) work similarly in other peripheral tissues.

The class of medication commonly used to treat type 2 diabetes increases the production of insulin in the pancreas. This type of medication is most effective in those with type 2 diabetes who have a lower production of insulin. The most common group in this class is referred to as sulfonylureas (some brand names are Amaryl, Diabeta, Diabinese, Dymelor, Glucotrol, Glynase, Micronase, Orinase, Tolinase). This type medication has been used for nearly half a century and has been improved, making it one of the most cost effective. Furthermore, because this type of medication increases your insulin levels, it is possible that you may experience hypoglycemia when taking them, especially when increasing your activity levels. Weight gain has also been associated with this class of medications. And again, to prevent hypoglycemia with exercise, you need to understand the symptoms and monitor your blood glucose levels when increasing your exercise duration or intensity. The newer drugs in this class of stimulators of insulin secretion (including Amaryl, Diabeta, Glucotrol, Glynase, and Micronase) have a quicker onset and a short duration, which may help lessen complications related to hypoglycemia and weight gain.

There is currently one other class of oral medication that can be used to decrease the blood glucose. These medications (acarbose, brand names Prandase and Precose; and miglitol, brand name Glyset) work by decreasing the absorption of carbohydrates from the gastrointestinal tract. The medications inhibit a crucial step in the breakdown of carbohydrates before they can be absorbed through the intestine into the bloodstream. However, because these medications need to be taken at the beginning of each meal, and common side effects are gas production and flatulence, these are used to a lesser extent than the three classes of drugs described previously.

People with type 2 diabetes who are having difficulty controlling glucose levels with exercise, diet, and one (or a combination) of oral medications may need to take insulin in a similar manner to those with type 1 diabetes. Frequent glucose monitoring is important here as well.

Other Medications and Supplements

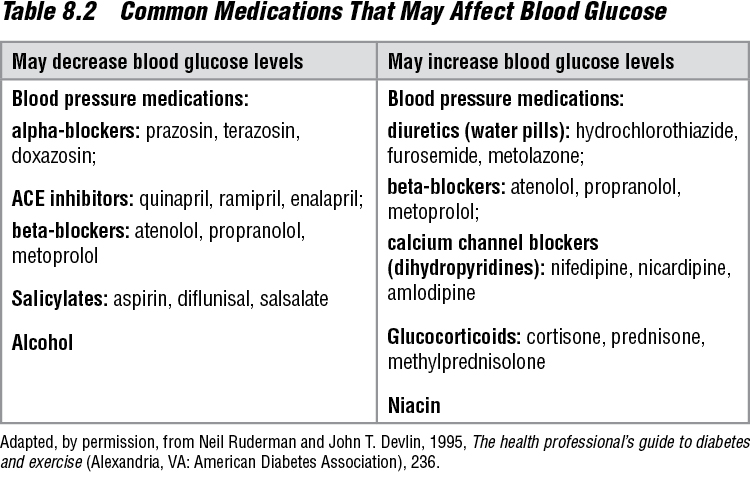

You probably have encountered other medications or nutritional supplements at some time. Before starting your action plan for diabetes, meet with your physician to review all the medications or supplements that you are taking or that you plan on taking. There are several common medications that you may use for conditions other than diabetes, which may increase or decrease your blood glucose levels (see table 8.2). In addition, you may wish to use nutritional or ergogenic supplements to enhance your overall program. With the exception of the two supplements chromium and creatine (which I discuss later), I will not talk about supplements specifically.

Many supplements are available that may or may not be as effective as their labels claim. In addition, many of the supplements have not been investigated thoroughly enough to allow manufacturers to make truthful or accurate claims; this can pose a danger to anyone taking them. But more important, if you were to take a supplement and there was an unanticipated effect on the blood glucose level, it could result in a significant problem with your action plan for diabetes. My personal stance on nutritional supplement use (other than multiple vitamins) in people with diabetes is that their use should be discouraged until we have more definitive information about their effects on glucose control. However, as more data become available, supplements may have a place in the treatment of diabetes. With further research, the following supplements may prove to be of some benefit to people with diabetes.

Chromium Picolinate

Chromium picolinate (the most popular form of chromium) is a trace mineral found in the human body that is required for carbohydrate and fat metabolism. It is thought that chromium helps insulin bind to the cells’ receptors, thus enhancing insulin sensitivity. In fact, some researchers have reported significant decreases in hemoglobin A1C and total cholesterol values in those with type 2 diabetes who supplement with 500 micrograms of chromium picolinate (a higher dose than the estimated safe and adequate daily dietary intake [ESADDI] of 50 to 200 micrograms) (Anderson et al. 1997). In addition, multiple studies have shown that chromium supplementation does not increase body mass, strength, or muscle size as once thought. However, another study has shown that people who were taking chromium lost significantly more body weight and fat than those on similar diet plans who were not taking chromium (Kaats et al. 1996). Recognize that we need more research in these areas to generate sufficient evidence before we can make the statement that chromium picolinate is safe and effective in treating diabetes.

Before going full-steam into your exercise program, it’s crucial to know if your medication has any interactions with exercise.

Creatine

Creatine is a popular nutritional supplement used in the amateur and professional fitness world. It is a substance made in the liver, pancreas, and kidneys, but it can also be acquired from eating meats and fish. Creatine has been shown to increase muscle strength and muscle size as well as increase fat-free (lean) mass in conjunction with strength training (Becque et al. 2000). Interestingly, researchers have reported that creatine may facilitate the removal of glucose from the blood and may reduce gluconeogenesis (new production of glucose) in the liver in people with type 1 diabetes who have high blood glucose levels (Rocic et al. 1991). As with all supplements, much more definitive research needs to be done on creatine and glucose control before its use can be recommended in people with diabetes.

The study of nutritional supplements is a very active field, and many of the data available do not pertain to the enhancement of the treatment of diabetes. Thus, I do not recommend using any supplements without the guidance of your health care team, especially in the initial phases of your plan when you are vulnerable to other problems. At this point I do not encourage supplement use in my patients with diabetes because of lack of evidence of their safety or efficacy.

Whether you take a medication to control your glucose or are contemplating adding a supplement to your diet, you should now have some understanding of how these substances may affect your health. Keep abreast of changes in medications that you are currently taking and the development of new ones, and check with your doctor before making any changes to your diabetes treatment. These steps will help you stay on top of your action plan.

Action Plan:

Taking Medications and Supplements

• Know which medications are available for your type of diabetes, and research those medications further, especially if you are taking one.

• Talk to your doctor about how your medication may be affected by changes in exercise or diet. This should be done before making any changes.

• Be aware of the possible side effects of the medication you are taking and how to avoid or deal with them.

• Consider and talk to your doctor about the possible use of supplements, but do not proceed with use until you’ve carefully and thoroughly researched the options. Know the pros, cons, and risks of each one.