Gloucester survivors at the war memorial, Plymouth Hoe, 1992. (L to R) Frank Teasdale, Billy Grindell, Ernie Evans, Maurice o’leary, Bill Howe, Bill Wade, John Stevens.

S am Dearie was eventually flown home following his release. His father had died in 1943, while Sam was being held prisoner but his mother made sure that he had a traditional Glaswegian welcome. Sam kept a newspaper cutting from the Glasgow times, which recorded his homecoming;

‘on active service repatriated; Dearie.

Mrs S Dearie wishes to thank Newbank

Welcome Home Fund committee for the

social evening and gifts to her son

Samuel on his return from Germany.

49 Glammis road, e1.’

Peter Everest, the young boy seaman who had joined Gloucester as his first ship, just four days before her sinking, remembered the joy of his liberation;

‘We were in a camp near Salzburg when the Americans reached us. They gave us Lucky Strike cigarettes and chocolates. It was wonderful although the next day everybody was ill with stomach upsets and had to be given castor oil’.

A few days later he was flown to England and arrived home just before his 21st birthday. Peter’s mother did not know that he was due to arrive and was amazed to see her boy, who had left home when he was only sixteen, standing on the doorstep.

Bob Wainwright eventually reached his home in Newcastle Upon Tyne and had an emotional reunion with his family.

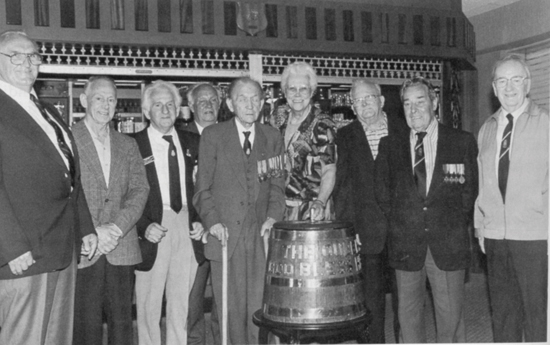

Gloucester survivors at the war memorial, Plymouth Hoe, 1992. (L to R) Frank Teasdale, Billy Grindell, Ernie Evans, Maurice o’leary, Bill Howe, Bill Wade, John Stevens.

Tot time with the Mayor of Plymouth, 1990. (L to R) reg Wills, Frank teasdale, John Stevens, Fred Farlow, Maurice o’leary, Bill Wade, Billy Grindell, Ken Macdonald.

John Stevens was flown home in a Wellington bomber;

‘As we approached england the pilot invited us to go up to the flight deck to see the white cliffs of Dover. It was a most emotional sight and when we landed at Oxford all I can remember seeing was lads getting down to kiss the ground’.

John travelled to his home in Essex where he was greeted by the sight of ‘Welcome Home John’ banners strung across the street. He recalls that people who he had never met before came up to shake his hand.

Billy Grindell flew back with Lt Cdr Heap and Surgeon Lt Singer both of whom were delighted to see him again. Billy later travelled to Wales by train, with Ted Mort. Ted left the train at Newport while Billy continued on to Cardiff where he saw his daughter, Margaret, for the first time: she had been born after Gloucester sailed in 1939.

In Newport, Ted Mort got off the train and set out on the happy walk to his home. He knocked at the door and was perplexed that there was no answer. A neighbour, seeing him at the door, came out and broke the terrible news that his mother had died and his father had moved to the Cotswolds in order to get work. It was a dreadful homecoming for the young sailor.

Ernie Evans had a delayed homecoming as he was detained in hospital for a while because of the injuries to his legs which he had sustained in Stalag XVIIIA. When he did arrive in Plymouth he couldn’t believe the state the city had been left in by the bombing and he found it difficult to find his way home with so many familiar landmarks gone. When he eventually got there a ‘Welcome Home Ernie’ banner was flying across the street.

Bill Howe had spent most of his period as a prisoner separated from the other Gloucester survivors. He was released by American soldiers and flown back to England where he was issued with a travel warrant to Bovey Tracey, the nearest railway station to his home village of Manaton, on Dartmoor. On the journey he had to change trains at Newton Abbot and he took the opportunity to telephone a friend of the family and inform her that he was on his way home. When Bill arrived at Bovey Tracey, the lady was waiting to drive him home in style in her Austin Seven. Bill’s father had been the sexton at the village church and, as a boy, Bill had learned to ring the bells. When the car drove into the village the road was packed with people to welcome him and the church bells were ringing out;

‘My mother was in tears when she saw me. I had weighed 12 stone when she had last seen me and I was only eight stone when I got home’.

There were 810 men aboard HMS Gloucester when she was destroyed on 22 May 1941. Only 83 survived to come home at the end of the war in 1945.

The men and boys who lost their lives continue to be remembered by the remaining survivors and their families who gather each year at the Royal Naval War Memorial on Plymouth Hoe on the anniversary of the sinking of their ship;

HMS Gloucester: ‘The Fighting G’.