Emily remained even-keeled even when seasick. “Judging from the fine flavor of carrot with which the operation ended, the greedy old ocean coveted even the soup I had eaten for dinner,” she reported. “Probably when I am shut down in the cabin tonight I shall have another tussle with destiny, but if this weather continue I shall not know much of the horrors E was so troubled by.” She had sailed from Boston at the end of March 1854, spending her last night with Nancy Clark, who saw her aboard with a bouquet of roses and a generous supply of biscuits.

The Royal Mail Steamship Arabia, built for the Cunard line only a year earlier, was magnificent: nearly a hundred yards from stem to stern, with two masts, two smokestacks between them, and two huge paddlewheels on either beam. The main dining saloon, with seating for 160, was paneled in bird’s-eye maple and ebony, hung with crimson drapes, and upholstered in velvet, with glowing stained-glass sconces depicting camel caravans “and other Oriental sketches” in keeping with the ship’s name. Steam pipes beneath the floor warmed the staterooms, which were similarly done up with Brussels carpets and more red velvet.

Emily ignored its luxurious charms, perching contentedly in the lee of a smokestack, watching gulls tumbling in the sea-salted wind. Cresting waves foamed like spouting whales, and real whales spouted among them; icebergs resembled mountains or ruins or, in one case, “a little solitary watch tower.” Even rough weather was gorgeous, and once she was safe in her berth, the crashing sea rocked her to sleep. Her young roommate—“an inoffensive Irish girl”—might wake her screaming that a ghost had invaded their cabin, and her fellow passengers might weary her with their “drinking smoking cardplaying & crowding,” but these were passing irritations. The natural world continued to be Emily’s solace.

Her solitary hours offered time to reflect on the three weeks she had just spent in New York. A month after Emily’s graduation, Elizabeth had reached a milestone of her own: the opening of her dispensary. Following Daniel Brainard’s instructions scrupulously, she had obtained a charter from the state and stacked her board of trustees with prominent men—many of them Quaker and several the husbands of satisfied patients. They included the Tribune editor Horace Greeley and his deputy Charles Dana; Henry J. Raymond, politician and recent founder of the New-York Times; and the jurist Theodore Sedgwick.

“The design of this institution is to give to poor women an opportunity of consulting physicians of their own sex,” Elizabeth’s carefully crafted mission statement began. “The existing charities of our city regard the employment of women as physicians as an experiment, the success of which has not yet been sufficiently proved to admit of cordial cooperation.” At the end of a list of respected doctors who would serve as consultants, Elizabeth’s name was tucked in discreetly as “attending physician.” The minutes of an early board meeting suggest that even her trustees considered female physicians a hard sell. The original draft of their incorporation certificate softened the mission by stating that they would employ “medical practitioners of either sex,” though it was “the design of this Institution to Secure the Services of well qualified female practitioners of Medicine for its patients.”

The institution’s name—the New York Dispensary for Poor Women and Children—was the grandest thing about it. Elizabeth had found a single small damp room on East Seventh Street, near Tompkins Square in the heart of Little Germany. She tacked a card to the door announcing the hours—Monday, Wednesday, and Friday, from three o’clock—until a more permanent tin sign could be painted. And three afternoons a week, instead of sitting in her room on University Place, she walked the mile to Seventh Street, and sat there.

The homely dispensary might not have matched what Elizabeth had imagined during her months of training in Europe, but it suited her approach as a physician. The tenement-dwelling seamstresses and cigar-makers who came for basic remedies also received guidance on household hygiene, ventilation, diet, child care—everything Elizabeth had described in Laws of Life for the wealthier women uptown. She dispensed job advice, recommended charities, and even handed out “pecuniary aid” to the most desperate. Sometimes she followed up with a visit to a patient’s home. Elizabeth was practicing social work as much as medicine, and she was gratified to note that “in many cases the advice has been followed, at any rate for a time.” The flow of patients wasn’t more than a trickle, but that was beside the point: Elizabeth’s institution existed at last, and it was a place to start.

Emily had passed through New York from Cleveland just as the dispensary opened. She spent nearly three weeks helping Elizabeth in her new venture, noting only that bare fact in her journal without further comment. Here was Dr. Brainard’s advice in action, Elizabeth’s newborn organization, awaiting Emily’s more permanent help once her training was complete. But it was tiny, humbly situated, and had more to do with cough syrup and constipation than the newest advances in obstetric surgery. Emily was not sorry to be leaving for the operating theaters of Edinburgh and Paris. And perhaps Elizabeth felt a twinge of envy as she watched her go.

Upon her arrival in Liverpool, Emily gazed at her mother country with the eyes of a delighted tourist. Only six when the Blackwells emigrated, she thought of herself as American in a way Elizabeth never had; now back in Britain for the first time, “the people struck me as remarkably English.” She paused at the edge of a crowd of children to watch a red-nosed Punch waving his pasteboard sword at a blue dragon with snapping jaws. Passing a baker’s window full of “the most tempting plum buns, of course I went in and bought two.” On the train to Birmingham, she gazed at the pastoral landscape: lambs, cottages, orchards. “It all had a sort of toyshop look,” she wrote, “everything was so neat and finished, so green small & trim.” Where Elizabeth had returned to the old country and saluted its superiority, Emily found it quaint.

The letter Emily had sent announcing her travel plans had taken a slower steamer than the Arabia, so she entertained herself by surprising the siblings she hadn’t seen in nearly six years. Anna hadn’t gotten up yet; her little sister’s face peeping around the bed curtains produced, to Emily’s delight, “a look of such bewildered amazement as is quite impossible to describe.” Hearing Howard’s voice in the parlor, Emily carried in the morning papers with a nonchalant “good morning.” “If ever an apathetic youth opened his eyes,” she wrote, “that young gentlemen did so then.” Emily found her oldest sister and younger brother changed: Anna had gone gray, Howard was now bewhiskered, and both of them had erased Cincinnati from their accents and their dress. After lunch they went for “a real English walk, gathering kingcups and daisies from the hedgerow.”

Emily wasted even less time than Elizabeth on family reunion, pushing on within days to London, where ever-helpful cousin Kenyon accompanied her on introductory visits to notable physicians. These included Elizabeth’s mentor at St. Bartholomew’s, James Paget, who was happy to see “another Dr. Blackwell” and heartily endorsed Emily’s intention to study with James Young Simpson in Scotland. She met Elizabeth’s friend Barbara Leigh Smith, who embraced her warmly and carried off a small stack of Emily’s newly printed calling cards to share with well-connected friends. She toured St. Paul’s and Regent Street and the British Museum with interest, but the works of artists and architects never touched her as deeply as the works of nature, and she was impatient to move on. Before she left for Edinburgh, Kenyon’s wife, Marie, presented her with a gold brooch as a parting gift—an elegant French one rather than the gaudy enameled pins that were the current fashion. After all, Marie insisted, for Cousin Emily, “il faut absolument quelque chose de sérieux.”

The dramatic scenery on the journey to Edinburgh, as she rattled along in the cars of the Great Northern Railway, was much to Emily’s liking. “The hills grew bold & bare,” she wrote, opening into broad valleys cradling “little old villages of grey stone looking so solemn & antediluvian.” Soon the hilltops glittered with lingering snow reflecting the last light of dusk; as they crossed the border at Gretna Green, Emily was lulled to sleep. Stumbling through a groggy arrival in the dark, she found her way to a bed at the Caledonian Hotel and awoke the next morning to a view, framed in her window, of Edinburgh Castle high on its crag.

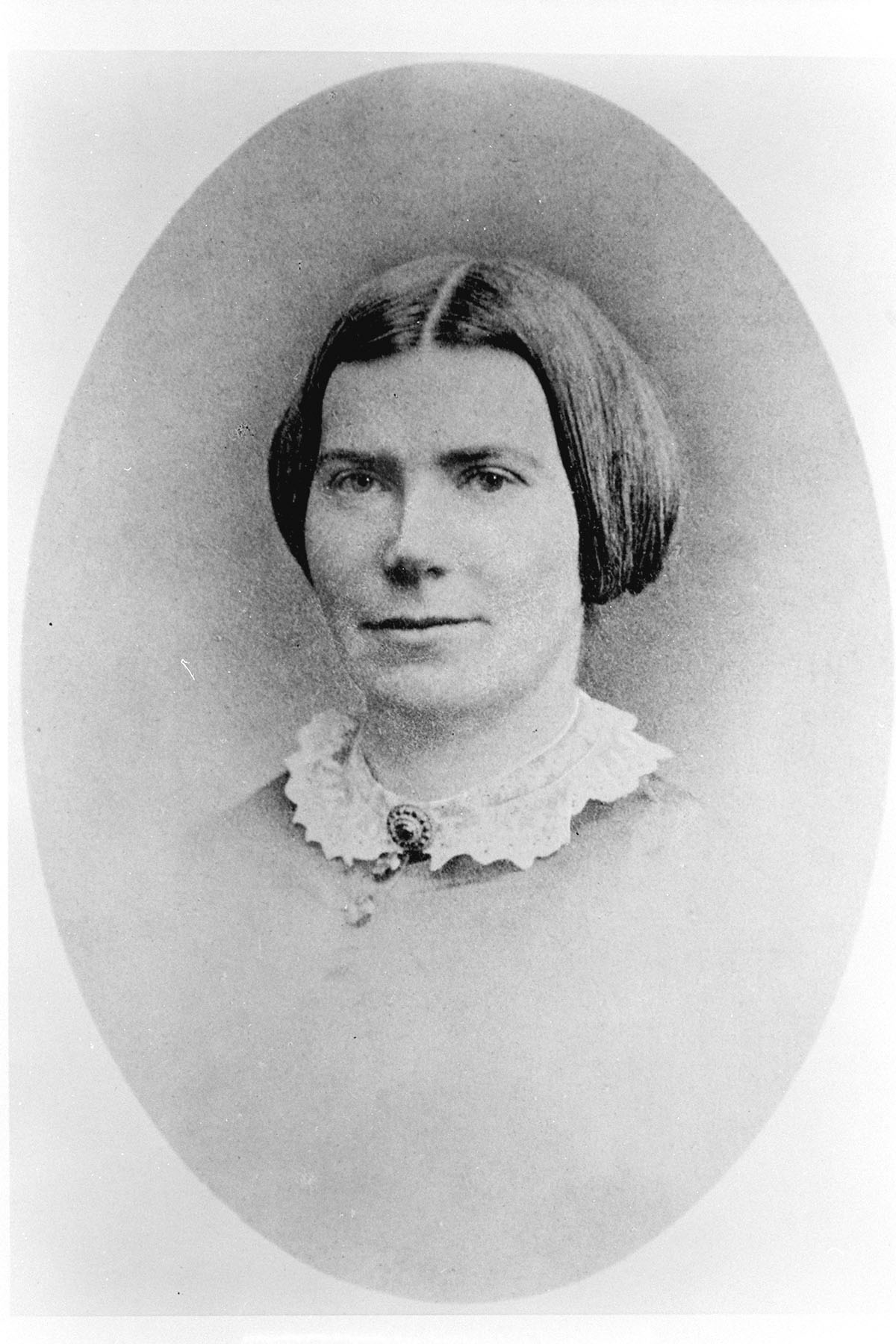

EMILY, CIRCA 1855.

COURTESY SCHLESINGER LIBRARY, RADCLIFFE INSTITUTE, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

The University of Edinburgh had long been considered the best place to study medicine in the English-speaking world—the founding professors of America’s first medical school, at the College of Philadelphia in 1765, had been Edinburgh graduates. Its population nearing two hundred thousand, the city had recently remade itself; in the New Town, north of Princes Street, rows of graceful terraced houses marched in stately contrast to the overflowing vertical squalor of the Old Town’s ancient closes. Emily did not pause to consider the legacy of the Scottish Enlightenment, or her friendless arrival in an ancient city. As soon as she was dressed, she set out for 52 Queen Street, the home and headquarters of James Young Simpson.

In 1854 Simpson was a man in his exuberant prime, having held the University of Edinburgh’s chair in midwifery and the diseases of women and children for nearly a decade and a half. He had been appointed physician to the queen in Scotland in 1847, the same year he became famous as the discoverer of chloroform as an effective anesthetic—a discovery he had made at his dining table in the company of several friends, each of whom inhaled a sample poured from Simpson’s brandy decanter, felt a wave of giggling euphoria, and promptly crashed unconscious to the floor. His house, in the heart of the New Town, was—and still is—the only one in the row with a full fourth story, added to accommodate his seven children, his ever-expanding private practice, and the never-ending salon of writers, artists, statesmen, and physicians who joined him at breakfast, lunch, and dinner.

Emily presented herself at the pilastered front door of Number 52 and made the immediate acquaintance of Jarvis, Simpson’s loyal butler and watchdog. “The servant who answered the bell was evidently well practiced in keeping people out,” she wrote wryly. “He declined with the most inexorable politeness to take even the letter I had brought. . . . I should think a dozen ladies were sent off in the same satisfactory manner within five minutes.” Emily waited several days, exploring the labyrinth of the Old Town. Simpson had been laid up with an attack of influenza, she learned—likely a cover for a bout of the depression that periodically halted his hectic schedule.

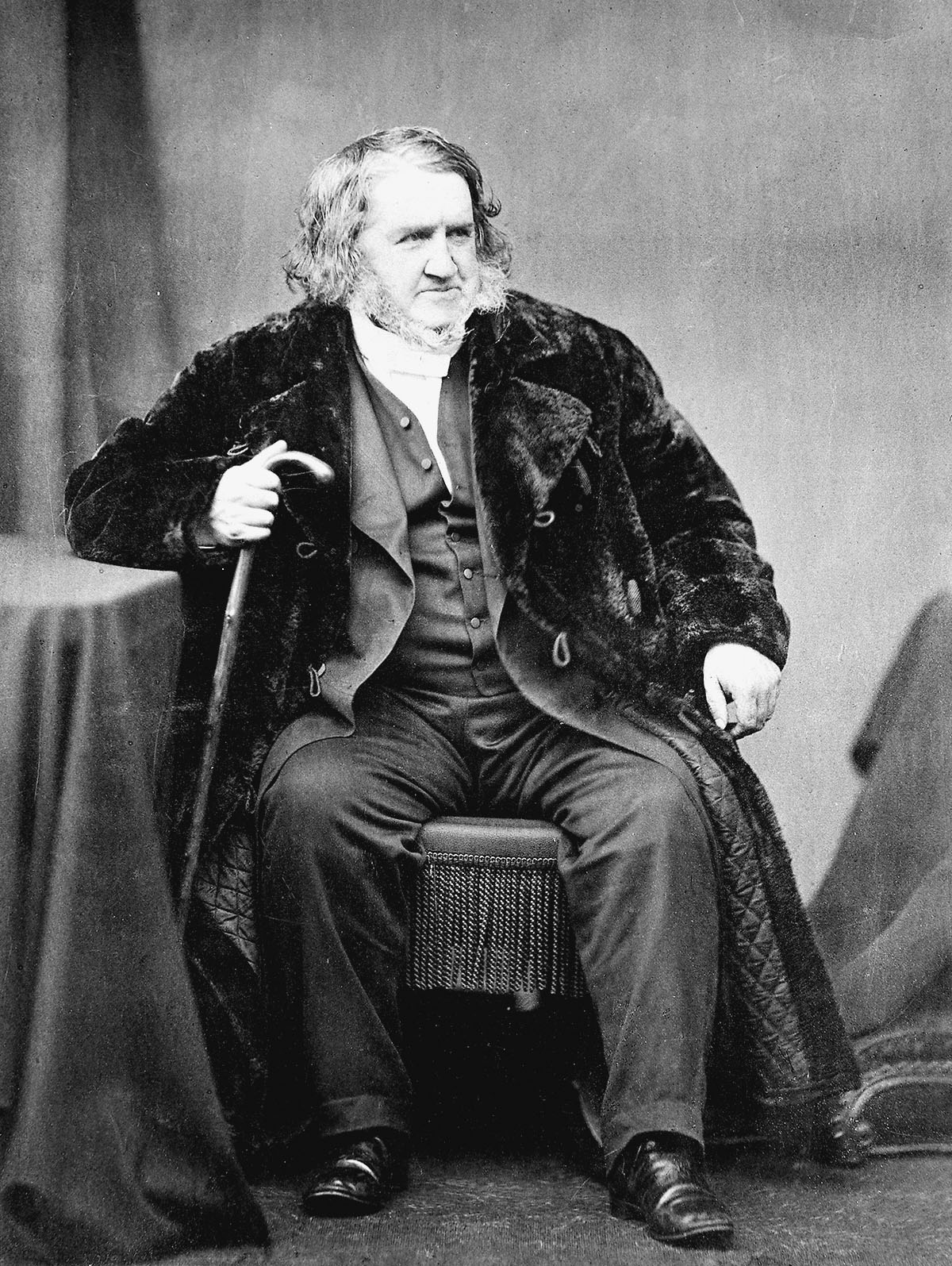

Her patience was rewarded. On her next visit to Queen Street, Jarvis escorted her through two long reception rooms full of patients to a sky-lit staircase at the rear of the house, where the great doctor’s monogram was worked into the uprights of the wrought-iron banister. Emily ascended to Simpson’s office. “I was received by a rather short stout man with a broad full rather flat face surrounded by a quantity of black wavy hair just touched with grey,” she wrote. Barrel-chested and shaggy-maned, Simpson cut an unmistakable figure, with a shrewd gaze flashing from a somewhat porcine visage. William Makepeace Thackeray, part of the parade of guests at Simpson’s table, described him as having the head of Zeus.

JAMES YOUNG SIMPSON.

COURTESY WELLCOME COLLECTION

Simpson shook Emily’s hand and invited her to sit, clearly enjoying the effect on his startled patients when he addressed her—loudly and repeatedly—as “Dr. Blackwell.” “There was one young English lady in particular,” she recounted, “whose eyes really seemed as though they would never return to their ordinary size.” That evening Emily accompanied Simpson and his wife and sister-in-law to their seaside retreat, Viewbank, near the fishing village of Newhaven on the Firth of Forth. After dinner they walked the rocky beach, peering into tide pools as Simpson pointed out limpets and jewel-toned anemones, hermit crabs and fossils—exactly the kind of ramble Emily liked best, in wondrous new surroundings. Mrs. Simpson and her sister dropped back discreetly, allowing the two doctors to talk. “I told him just what I wanted to do and he cordially offered to aid me in accomplishing [it],” Emily wrote. “It was past nine o’clock, but broad daylight, when, with very wet feet and very tired—but extremely satisfied with my first interview with Dr. S—I took leave, and they sent me home in their comfortable carriage.”

Thus began Emily’s transit in the crowded orbit of James Young Simpson. The next day she found the doctor at lunch, “surrounded by a perfect levee of friends who, any at least who were so inclined, sat down & took coffee &c with the most unceremonious freedom.” All of them shifted their avid attention to this latest curiosity in Simpson’s collection, talking to—and at—Emily until at last their host summoned his newest student to his busy consulting rooms.

Patients made their way to Queen Street starting at daybreak. The especially wealthy or notable were pointed straight up the front stairs by the ever-present Jarvis, and everyone else was directed to the waiting rooms at the back, to perch where they could after drawing a number in the order of their arrival. Most of these visitors were seen by Simpson’s assistants, the man himself being out as much as he was in: lecturing at the university, making rounds at the Royal Maternity Hospital, or dashing between the grand homes of his wealthiest patients in his carriage. (His pocket pill case, with compartments for opium, morphine, and calomel, was labeled “Please return to 52 Queen Street” beneath the lid.) Any irritation at the endless waits and exorbitant fees, however, melted away in the presence of Simpson’s equally outsized personality. He had the gift of attentiveness: every woman who came within range of his rosewood and ivory stethoscopes felt comforted and understood. “I believe I shall find my connexion with Dr S most fortunate,” Emily wrote with cautious optimism. “He tells me to ‘come about the house like one of the family’ and see what he can show me.”

Emily’s work with Simpson proved to her that a patient’s opinion of female doctors was usually in inverse proportion to her wealth. At Queen Street, even those who warmed to the idea of confiding their intimate troubles to a woman often balked at the impropriety of expanding the feminine sphere to include the medical profession. American women were a “fast set,” they told each other, and women doctors clearly the “wild developments of an unreliable go-ahead nation.”

Among the working class, Emily found no such issues. She took lodgings at Minto House, once an aristocratic residence, now converted to a small lying-in hospital in the crowded Old Town, with the steeple of Tron Kirk rising across the way. Minto House was a well-chosen address: it was cheap and respectable, and Emily could observe the half-dozen cases the hospital admitted each week and put her name on the list of students on call for “outcases.” The indigent patients she saw there, and in the steep closes off the High Street and Canongate, cared not at all about the legitimacy or the propriety of her training.

EMILY’S TICKET FOR OBSERVATION AT EDINBURGH MATERNITY HOSPITAL, MINTO HOUSE, 1854.

COURTESY SCHLESINGER LIBRARY, RADCLIFFE INSTITUTE, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

Haring off down filthy passages and up narrow stone staircases in the wee hours to overcrowded rooms six or eight stories above the street could be unnerving, but the matron of the hospital pointed her toward the “most decent” patients. Emily became accustomed to her knock just as bedtime beckoned. “You wad’na be wanting another case tonight?” the matron would ask through the door. “There’s an old body in haste for someone to her daughter—they live all alone in the house.” In other words, there would be no degenerate males to threaten the lady doctor. Regretting the loss of sleep but grateful for these midnight opportunities, Emily was sometimes out past three in the morning, though by then, in the Edinburgh summer, the sky was already growing light.

Her nocturnal experiences among the Old Town poor were an important complement to her daylight hours at Queen Street, where there was more watching than doing. Then again, James Young Simpson was worth watching. Now Jarvis waved her straight in and upstairs to Simpson’s three connected consulting rooms, their walls covered in richly colored velvet. Simpson’s own sanctum was the Red Room, while Emily generally stationed herself next door in the Green Room, waiting to be called upon to take a patient’s history or even perform an examination—and keeping her lack of clinical experience carefully to herself. “I looked grave and did not tell him how very little I was able to detect during my first experiments,” she confessed to Elizabeth. When Simpson sent her on a house call to a patient who needed to be bled for a gynecological complaint—requiring the application of leeches to her cervix—Emily was grateful no one from Simpson’s practice was there to witness the clumsy job she made of it. “Today he has ordered leeches that I may apply them at his house,” she worried. “How I shall succeed I don’t know.”

Most of Simpson’s patients consulted him about ailments rather than pregnancy, and it was his innovation never to make a diagnosis without a pelvic examination. He took measurements of internal anatomy by means of a uterine sound—a curving metal probe engraved with calibrations—and felt for abnormalities of the uterus and cervix manually. “He makes a physical diagnosis of diseases of those organs just as he would of the chest, throat, &c,” Emily wrote, surprised. “Nevertheless he is so skillful that in practice he conducts these examinations with little annoyance to his patients.” Indeed, “his finger appears to have sight as well as feeling,” she wrote with growing admiration. Simpson would have used his hands more than his eyes; though he was a pioneer in the use of the speculum, modesty dictated that much of the examination still happen out of sight, beneath the patient’s skirts.

Emily had built up a degree of immunity toward charismatic medical men: from the start, she understood that Simpson’s charm obscured the limits of his skill as a diagnostician and surgeon. “He has made in this way many remarkable cures—has killed a good many whom he says little about—has improved a very great many and has persuaded still more by his enthusiasm and firm conviction of the benefits of his treatment that they are much better when there was really not much difference,” she wrote—an observer fully aware that the emperor was not always fully clothed. Emily had always chosen sincerity over glamour. Her professional reputation would be built on stronger science.

It did not escape her that Simpson performed his most daring experiments on charity patients. Mostly, however, his practice attracted the fashionable and the fortunate. “I have not seen a single case of syphilis or gonorrhea,” Emily noted. “He seems not to have it among his patients.” Some of their problems—various cancers, fibroid tumors—required surgical procedures with which Emily was familiar, but many were more ambiguous. “Through August & September he has a great many English patients,” she wrote. “The gentlemen come north to shoot & their wives spend the time in Edinburgh being doctored!” Younger women presented with dysmenorrhea or amenorrhea: menstrual discomfort, or a failure to menstruate at all. Middle-aged matrons suffered from uterine prolapse—the toll of too many pregnancies, resulting in the displacement of the uterus into the vagina—or perimenopause, with its shooting pains and gushing periods.

Anna, similar to these vacationing patients in her concerns if not her cash flow, wrote to Emily seeking Simpson’s advice. “Period generally about five weeks apart, but irregular; discharge always full of clots, some nearly black, like coagulated blood, some (smaller) bright red, like specks of raw meat,” she reported with her usual graphic zeal. The list of symptoms went on for pages. “I should much like to know Dr. S’s opinion of my case,” she concluded. She did not ask for Emily’s.

Popular gynecological remedies of the day ranged from hipbaths, prune juice, and leeches to the lower back, to mustard poultices, arsenic, suppositories, and fizzy lemonade. Simpson took a different approach. For many women, sometimes regardless of complaint, Simpson prescribed and inserted a “galvanic pessary” of his own invention: a copper disc with a stem of copper and zinc that he slid deftly into the cervix, and that patients professed not to feel at all. Pessaries were commonly used to support the internal organs of the pelvis and help keep them in place; Simpson claimed his had additional electrochemical benefits. “I have yet to be perfectly convinced that there is a real galvanic current at work,” wrote Emily. “I want to find some kind of galvanometer by which to ascertain that fact.”

One of the ladies who arrived to consult Simpson that summer was Emily’s own cousin-in-law Marie, Kenyon’s wife. She was suffering from a case of “stricture,” a stenosis or narrowing of the cervix to which she and Kenyon likely attributed their failure to conceive a child. Simpson promised to cure her in a fortnight by surgically enlarging, or “dividing,” the cervix, a procedure he performed frequently using an instrument called a metrotome, an elongated switchblade with a hidden edge that opened outward when the handles were squeezed. He inserted it into the cervix, deployed the blade, and then swiftly pulled it out, scoring a partial incision inside the length of the cervix. This was quickly repeated on the opposite side. Sometimes it helped, and normal menstruation and even conception followed. Sometimes, if the incisions were too deep, the patient hemorrhaged.

Elizabeth, upon reading Emily’s report of the situation, was dubious. Wouldn’t it be better to try dilation before surgery, stretching the cervix with a cylinder of waxed cotton, called a bougie, or a cone-shaped piece of sponge, known as a sponge tent? Wouldn’t surgical scarring only make the constriction worse? Elizabeth’s concern was more professional than personal but no less correct; today cervical stenosis is not corrected with surgery.

STEM PESSARY.

COURTESY NATIONAL MUSEUM OF HEALTH AND MEDICINE, PHOTO BY MATTHEW BREITBART

The familial presence of Kenyon and Marie, and the rare opportunity to follow one of Simpson’s patients over a longer term, made up for a disappointment that might otherwise have hastened Emily’s departure from Edinburgh. Despite Simpson’s support for her application to walk the female wards at Edinburgh’s Royal Infirmary, permission was denied. Someone leaked the rejection to the press, and dozens of British newspapers reported on Emily’s unprecedented request, some adding the patronizing untruth that Emily had “forthwith quitted the city in great chagrin at the ungallant reception she had experienced from her brother practitioners.” Emily was irritated but undaunted. “I wish while they were about it they would have added the fact that I had been studying with Dr S for six months,” she wrote. “Then I should think their notices might have done me a little good by making me known as the pupil of the first man in this department in Gt Britain.”

Emily had intended to move on to London and Paris—to St. Bartholomew’s and La Maternité—early in the fall, but although Marie endured her surgery without mishap, her recovery was difficult. Elizabeth encouraged Emily to remain in Edinburgh for Marie’s convalescence, lest she provoke an “ineffaceable hostility” in Kenyon, after all his generosity to his doctor cousins. The repeated delays allowed Emily to accompany Simpson to the university for the graduation of the medical class. She watched the president touch each man’s bowed head with an ancient flat black cap, murmuring te medicinae doctorem creo—“I create thee doctor of medicine”—as he handed him his diploma. Afterward, as Emily passed the platform on her way out, Simpson tapped her on the head with the ceremonial cap and recited the same invocation, “a joke which appeared much relished by his professional brethren,” she wrote, unsure whether to laugh along.

She was coming to understand the limits of Simpson’s esteem. “He rather likes the novelty of a woman Dr—has no objection to my being as far as possible indoctrinated into his view, and as I am sometimes useful does not dislike my being about his house and picking up what I can,” she mused. “But he does not care about the matter—he will not in the least put himself to trouble to aid me.”

The trouble Simpson had taken with Marie did not seem to aid her either—each treatment came with another setback. Inflammation, abscess, and ovaritis were compounded by the mouth sores caused by overuse of calomel, the mercury-based drug that Emily and other progressive practitioners had come to distrust. A frightening bout of peritonitis occurred while Simpson was out of town, and Emily spent a harrowing night at Marie’s side, blistering her abdomen and soothing the pain with laudanum-infused poultices. “The whole case from beginning to end strikes me as a horrid barbarism,” Elizabeth wrote from New York, voicing an opinion Emily refrained from stating explicitly. “I see every day that it is the ‘heroic,’ self reliant & actively self imposing practitioner, that excites a sensation & reputation; the rational and conscientious physician is not the famous one.” Emily could not regret the extra months in Edinburgh—“I believe it has made the difference of life & death to Marie,” she wrote, and acknowledged that taking responsibility for her cousin’s care had “made a Dr of me”—but she was ready to learn from others.

The news that Elizabeth’s friend Florence Nightingale was recruiting women to serve as nurses at Scutari in the Crimean War briefly piqued Emily’s interest—not so much for the sake of clinical experience in the field, as in hopes of accessing new connections and opportunities within the medical establishment. Once she understood that Nightingale would hold the only position of authority, and that only in the sphere of nursing, she dropped the idea, “as I shall not of course accept a subordinate position.” Elizabeth seconded this decision, unable to agree with Nightingale’s conviction that women should be nurses and leave the doctoring to men. She was increasingly dismissive of the efforts that would soon make Florence Nightingale a household name. “She will probably thus sow her wild oats,” Elizabeth wrote, “and come back and marry suitably to the immense comfort of her relations.” An English correspondent of The Una, a new American monthly “devoted to the elevation of women,” drew an explicit comparison between Nightingale’s success and Emily’s struggle. “It seems strange that it should be considered more unfeminine for Miss Blackwell to visit sick women in the Infirmary of Edinburgh,” the article pointed out, “than for Miss Nightingale to go to a foreign land, and live among the horrors of war, for the purpose of attending to sick men.” The Blackwells were contributors to The Una, which was founded by Elizabeth’s friend Paulina Kellogg Wright. The anonymous correspondent might have been Anna.*

The days shortened in Edinburgh, its greens and grays cloaked occasionally in snow but more often in slush, the rotund Simpson swathed always in a fur greatcoat, “in which article he is I verily believe broader than he is long,” Emily wrote. It was January 1855 before Marie was well enough to travel, freeing Emily to leave for London. With her went a letter from Simpson, proof that her extended stay had not been a waste of time. “I do think you have assumed a position for which you are excellently qualified and where you may, as a teacher, do a great amount of good,” Simpson began.

As this movement progresses, it is evidently a matter of the utmost importance that female physicians should be most fully and perfectly educated, and I firmly believe that it would be difficult or impossible to find for that purpose anyone better qualified than yourself.

I have had the fairest and best opportunity of testing the extent of your medical acquirements during the period of eight months when you studied with me, and I can have no hesitation in stating to you—what I have often stated to others—that I have rarely met with a young physician who was better acquainted with the ancient and modern languages, or more learned in the literature, science, and practical details of his profession.

Emily was pleased with this encomium, though its last line suggested that Simpson, for all his ringing approbation, still found the idea of a female physician uncomfortable. “Permit me to add that in your relation to patients, and in your kindly care and treatment of them,” he closed reassuringly, “I have ever found you a most womanly woman.”

* In the next issue of The Una, Elizabeth was quick to correct the aspersions the anonymous correspondent cast, not on Nightingale, but on the leading physicians of Edinburgh. “Our English correspondent alluded to the injustice which Dr. Emily Blackwell met with in Edinburgh,” she wrote in an unsigned piece. After pointing out that Emily had gone there to study not at the Royal Infirmary but with James Young Simpson personally, she concluded, “It is therefore with feelings of sincere gratitude that Dr. Emily Blackwell leaves the capital of true-hearted Scotland, and with the earnest hope that she may find elsewhere the same admirable facilities in the pursuit of her chosen profession.” Elizabeth was more interested in elevating women than in criticizing men. And even with the Atlantic between them, she could not resist quibbling with Anna.