“This medical solitude is really awful at times,” Elizabeth confided to Emily in Edinburgh, in the spring of 1854. “I should thankfully turn to any decent woman to relieve it, if I could find one.” Three days later she received a visit from a young woman with an austere severity about her dark hair and shadowed eyes, her strong jaw and wide mouth. By the end of the afternoon, Elizabeth knew she had found an ally.

Marie Zakrzewska was as ambitious and undaunted as Elizabeth herself. “With few talents and very moderate means for developing them,” Zakrzewska would write in her memoir, “I have accomplished more than many women of genius and education would have done in my place, for the reason that confidence and faith in their own powers were wanting.” Two years earlier she had achieved the impossible: appointment to the position of chief of midwifery at the University of Berlin. But her bad luck was as spectacular as her achievement, and on the day of her confirmation, her mentor and predecessor in the position died. Finding the politics and chauvinism of the medical community in Berlin untenable without his support, she emigrated.

She had spent the past year in New York trying and failing to continue her medical career. She spoke little English, but she would not consider nursing despite an invitation from a German doctor to serve as one. “I thanked him for his candor and kindness, but refused his offer,” she wrote. “I could not condescend to be patronized in this way.” After all, her mother had been a respected midwife, and her grandmother a veterinary surgeon. Her father was a scion of Polish nobility. Zakrzewska supported herself and the siblings who had followed her to America with a shrewdly managed business in knitted goods, and refused to concede her plans for a medical future. Doubt was not something she suffered from.

MARIE ZAKRZEWSKA.

COURTESY SCHLESINGER LIBRARY, RADCLIFFE INSTITUTE, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

Straining the limits of her German, Elizabeth listened to her visitor’s astonishing tale. Both as a physician and as an instructor, Marie Zakrzewska (pronounced Zak-SHEFF-ska and soon shortened, among the Blackwells, to “Dr. Zak”) was better qualified than Elizabeth. “She knows far more about syphilis than I do,” Elizabeth noted, “and has performed version 4 times”—this last referring to the tricky process of turning a breech baby in the womb before delivery. But penury and the language barrier rendered Zakrzewska’s credentials useless in America. Both her need for Elizabeth’s help and the depth of her experience ensured that she would reflect well on her benefactor. Here, surely, was the perfect deputy. “There is true stuff in her,” Elizabeth wrote immediately to Emily, “and I am going to do my best to bring it out.” Perhaps Zakrzewska could obtain her M.D. at Cleveland Medical College, as Emily had. “My sister has just gone to Europe to finish what she began here,” Elizabeth told her new protégée, “and you have come here to finish what you began in Europe.”

Elizabeth’s instant confidence in Zakrzewska stood in sharp contrast to her usual attitude toward women with medical ambitions, most notably Nancy Clark, currently the only female graduate of a regular medical college who wasn’t a Blackwell. “Yesterday little Mrs. Clark called on me,” she wrote to Emily. (“Little” Mrs. Clark was a year older than Emily. Neither Blackwell sister ever addressed her as “Dr.”) “Hers is a good little nature, with some shrewdness too, but she wants independent strength.” Elizabeth was unimpressed with Clark’s narrow focus on obstetrics rather than the broader science of women’s diseases and surgery. “This is evidently the natural tendency of present women,” she tsked, “instinct and habit, not intelligent thought.”

When Clark expressed her hope of joining Emily in Europe, both Blackwells were wary. “Would her companionship be unpleasant in any way?” Elizabeth asked her sister. “I don’t want her to depend too entirely on me,” Emily wrote back. “If she come and do at all well I will do all I can to help her.” It was fine for Clark to pursue her vocation, in other words, as long as she did it somewhere else. “I find it as much as I can do to maintain a respectable standing medically among the physicians I meet at the Hospital & in Queen St,” Emily told Elizabeth. “A more ignorant companion would certainly be no aid.” The Blackwell sisters had no time or patience for any woman who might hinder their progress. And though neither mentioned it explicitly, it was not to Nancy Clark’s advantage that, with her blue eyes and cupid’s-bow mouth, she was undeniably attractive. She was also financially secure and had a doctor brother who planned to accompany her to Europe, further smoothing her path. In the Blackwells’ opinion, Clark’s seriousness—despite her diploma—was suspect. “I fancy she’s a pretty little thing,” Elizabeth wrote, “& that’s about all.”*

Yet since Clark’s visit, Elizabeth had begun to question her own natural tendency toward solo superiority. In May she had attended a public lecture delivered by J. Marion Sims, a self-promoting surgeon known in his home state of Alabama for his experimental work repairing catastrophic vaginal and rectal fistula, the debilitating internal damage caused by prolonged obstructed labor. That he had practiced on enslaved women, without anesthesia, was something he downplayed to his contemporaries; later generations have condemned his ethics and questioned his legacy. Elizabeth knew him only as an ambitious outsider like herself, one who was rapidly drawing the attention of the New York medical establishment for a technique that could rescue afflicted women—prisoners in their homes, constantly leaking urine and feces—from a living death. (Sims’s surgical technique is today of vital importance in restoring women to independence in the developing nations of East Asia and sub-Saharan Africa.)

Elizabeth was intrigued by Sims’s stated goal of founding a hospital for the treatment of women—“much grander than anything I can hope to establish for many many years,” she noted—and paid him a call, offering her support. “He is thoroughly in favor of women studying, and will treat them justly, which is all we want,” she wrote to Emily, unaware of any irony. “He is a most fiery man, but with much sweetness nevertheless, honorable and a gentleman.” His hospital, she hoped, would be an ideal place for female medical graduates to train.

Sims’s apparent faith in medical women inspired Elizabeth to reexamine her own scornful attitudes toward her female peers. If exceptional women seemed scarce, it was Elizabeth’s responsibility to find and cultivate more of them. “You must settle this matter, Miss Blackwell, for yourselves,” Sims had told her: Women must elevate women and help each other “contribute to journals, get practice, show their force.” His advice was dismissive—but also very much in line with Elizabeth’s own thinking. She had never believed that the progress of women was the responsibility of men.

Connecting Zakrzewska to Emily’s allies in Cleveland, Elizabeth smoothed her path to admission at Cleveland Medical College in the fall. Meanwhile the newcomer from Berlin was the ideal assistant at the dispensary in Little Germany, where her native language was an asset. Not to mention her company. Elizabeth felt the imperative of maintaining her tiny institution as at once credential, laboratory, and rallying point for women pursuing medicine, but the daily reality was a trial. “My Dispensary business is rather wearisome,” she confided to Emily. “As it stands it seems to be of no special use except to give me a long hot walk.” That summer indoor temperatures reached ninety degrees. From cooler Edinburgh, Emily sent encouragement: “I look on the little dispensary with interest as affording us the means of practice among the poor and then testing new methods and making improvements.” The daily, steady effort of medical practice left Elizabeth unsatisfied and impatient. It attracted Emily profoundly.

Everything that Emily learned from James Young Simpson she reported faithfully in her letters to New York, filling the margins with sketches of instruments and techniques. She even sent a small pessary, which Elizabeth immediately tried out on a patient, unguided by anything other than Emily’s description. It took a few attempts and a little improvisation. “She cried oh just as I judge it entered the cervix, & oh again as it passed the cervix—she said it was not pain, but like a little electric shock each time,” Elizabeth reported. “It has been an immense satisfaction to have something rational that I could do.” Rejoicing in Emily’s famous mentor, she exhorted her sister to embrace her fortunate circumstances. “I do increasingly think that your position with the popular Dr Simpson, is a most rare chance for becoming known, both in America & Europe,” she wrote. “I very much wish you could stay there a year, thoroughly recognized as his pupil.”

But Elizabeth’s insistence that Emily remain abroad meant her own isolation in New York would continue. Marie Zakrzewska left for Cleveland Medical College in the fall of 1854; in her absence, Elizabeth closed the dispensary. Its limited hours had made it difficult to connect with the women of the neighborhood; on some afternoons, Elizabeth waited alone and in vain. Rather than spend her modest resources on rent for both residential and underused professional space, she decided, with the help of a generous loan from sympathetic friends, to buy a house at 79 East Fifteenth Street, at that time located between Irving Place and Third Avenue. Without a disapproving landlord, she would be free to see private patients and carry on her dispensary work on her own terms. It surely did not escape Dr. Blackwell’s notice that her new house backed onto the Fourteenth Street building that housed University Medical College, founded by New York University in 1841. For six years she would live within sight of its rear windows, even renting rooms to its students for extra cash. It would be another six and a half decades before New York University admitted a woman as a medical student.

Elizabeth was relieved to own a permanent home, and grateful for Marian’s housekeeping in the three years since her arrival in New York. But whether as helpmeet or intellectual companion, mild Marian could not satisfy Elizabeth’s craving for connection. Having eschewed marriage and motherhood for a career that existed more on paper than in practice, Elizabeth felt herself sliding toward depression. “I found my mind morbidly dwelling upon ideas in a way neither good for soul or body,” she wrote.

Passive resignation, however, had never been her style. One day in late September, Elizabeth boarded a ferry bound for Randall’s Island, northeast of Manhattan. Her destination was the juvenile department of the New York Almshouse, known as the Nurseries. She was going to pick out a child.

A five-minute walk from the ferry landing brought Elizabeth to a group of buildings built half a dozen years earlier, facing eastward into the salty breeze off Flushing Bay. Here lived more than a thousand children, ranging in age from three to fifteen. Some had been scooped from the streets, others deposited by desperate parents. Many were the children of recent immigrants: an “Infant Congress of many nations,” as one observer recorded, noting—in the unsettling cultural shorthand of the day—the round faces of the Germans, the “dogged look” of the English, the “pleasure-loving lips” of the French, the “whimsically grinning” Irish. It was a “great depot of small humanities,” Elizabeth wrote, “such forlorn children, assembled under harsh taskmasters, fast becoming idiots or criminals.” Inmates of the Nurseries went to school, but their training in the sewing workshops and the vegetable gardens was more important. The best way off the island was through indentured labor.

“I must tell you of a little item that I’ve introduced into my own domestic economy in the shape of a small girl,” Elizabeth announced to Emily, “whom I mean to train up into a valuable domestic, if she prove on sufficient trial to have the qualities I give her credit for.” The transactional tone is startling, especially when juxtaposed with the rosy sentimentality of some of Elizabeth’s writings on motherhood. But Elizabeth was less in search of a daughter than a useful companion. The small girl she chose—after several visits to look over the options—was Katharine Barry, a dark-haired, dark-eyed orphan of Irish parentage, thought to be about six years old. “She was a plain, and they said stupid child though good, and they all wondered at my choice,” Elizabeth continued. “I gave a receipt for her, and the poor little thing trotted after me like a dog.”

Removed from the institution, “Kitty” proved bright and diligent: “She is a sturdy little thing, affectionate and with a touch of obstinacy which will turn to good account later in life,” Elizabeth wrote approvingly. It was cheerful to wake in the morning to a child singing “Oh Susanna” as she waited for permission to leave her bed. She was instructed to address her new guardian as “Dr. Elizabeth.”

Elizabeth refreshed herself in the presence of Kitty’s innocence. Introducing her charge to the idea of the divine one Sunday soon after her arrival, she was charmed by the child’s response. “Oh nice God,” Kitty chirped. “I like God, doctor, don’t you?” Here was a stray soul to guide toward a better life, a tiny proof of all Elizabeth hoped to do for women. She liked to retell the story of Kitty’s reaction the first time she was introduced to a male physician: “Doctor,” she exclaimed, “how very odd it is to hear a man called Doctor!” Elizabeth enjoyed the challenge of this new experiment. “I have had, and I shall have a great deal of trouble with her, for she is full of intense vitality,” she wrote after a year of Kitty’s company, “but the results are worth the trouble.”

Living with a child forced Elizabeth out of her single-mindedness. “Oh Doctor, wouldn’t it be pleasant in the country today?” Kitty chirped one Sunday morning, and once she found her sunbonnet and filled her pockets with apples, off they set in the railcars that traveled up Second Avenue. A half hour’s ride brought them to Jones Wood on the East River—bucolic fields of buttercups and groves of tall oaks that, in the next century, would become the massive medical complex of New York–Presbyterian Hospital, Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Rockefeller University. Elizabeth settled herself in the shade to indulge in a long letter to her London friends, while Kitty floated woodchip “boats” in a pond nearby. “My friends here say they cannot imagine me, without this small shadow,” Elizabeth told Barbara Leigh Smith and Bessie Parkes in London.

Kitty, in return, enjoyed a secure if circumscribed position within the Blackwell clan, appreciated and educated—Elizabeth sent her to the new and progressive Twelfth Street School for Girls—but never permitted to marry or pursue her own path. In a memoir dictated after Elizabeth’s death in 1910, Kitty remembered her first encounter with the “very pleasant-voiced lady” who appeared on Randall’s Island to claim her. “She came at the sunset-hour, and found me with my hands clasped behind me, gazing at the setting sun. She asked me, would I be her little girl?” For the next fifty years, Kitty would embrace the role of acolyte.

Elizabeth took comfort in these additions to her household: Zakrzewska, a sister doctor to stand in for Emily; Kitty, a daughter to compensate for her childlessness. She was less pleased with two new family members whose choice lay outside her control.

While their sisters were building medical reputations in New York and the capitals of Europe, Henry and Sam had been—quite literally—minding the store, their latest venture a Cincinnati hardware business. One day in the fall of 1850, a small woman with large eyes in a round face approached the counter. She introduced herself as Lucy Stone.

As a dedicated reader of the abolitionist press, Henry knew exactly who she was. The first woman in Massachusetts to earn a bachelor’s degree, from Ohio’s Oberlin College, Stone had been lecturing on slavery and women’s rights for the last two years, sharing stages with Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and William Lloyd Garrison, whose radical views on abolition she heartily endorsed. Henry—who had been falling in and out of love regularly since he was a teenager—liked Stone’s politics, her famously bell-like voice, and her smile. But she was thirty-two and he was twenty-five. She might be a better match for his older brother Sam, he thought.

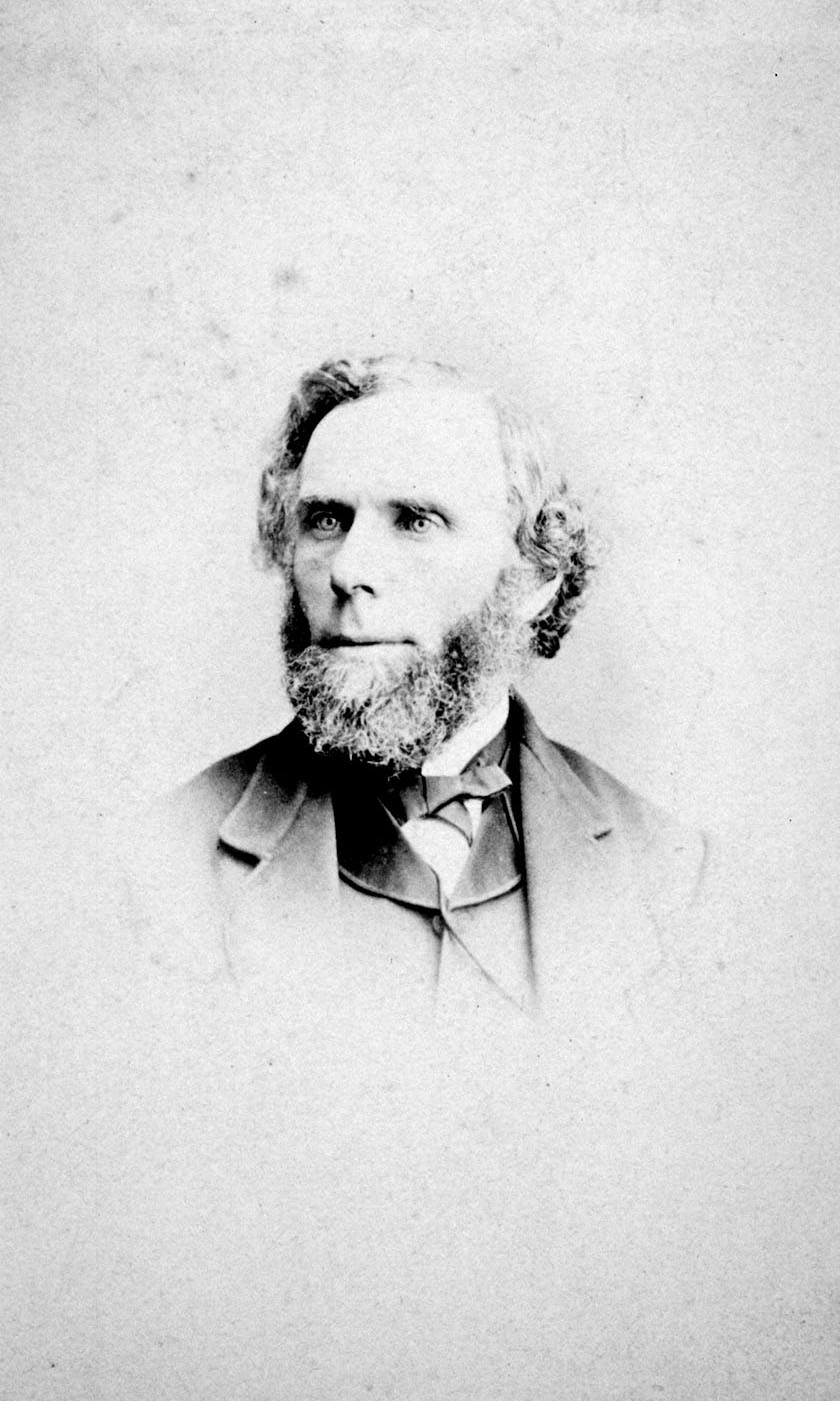

HENRY BLACKWELL.

COURTESY SCHLESINGER LIBRARY, RADCLIFFE INSTITUTE, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

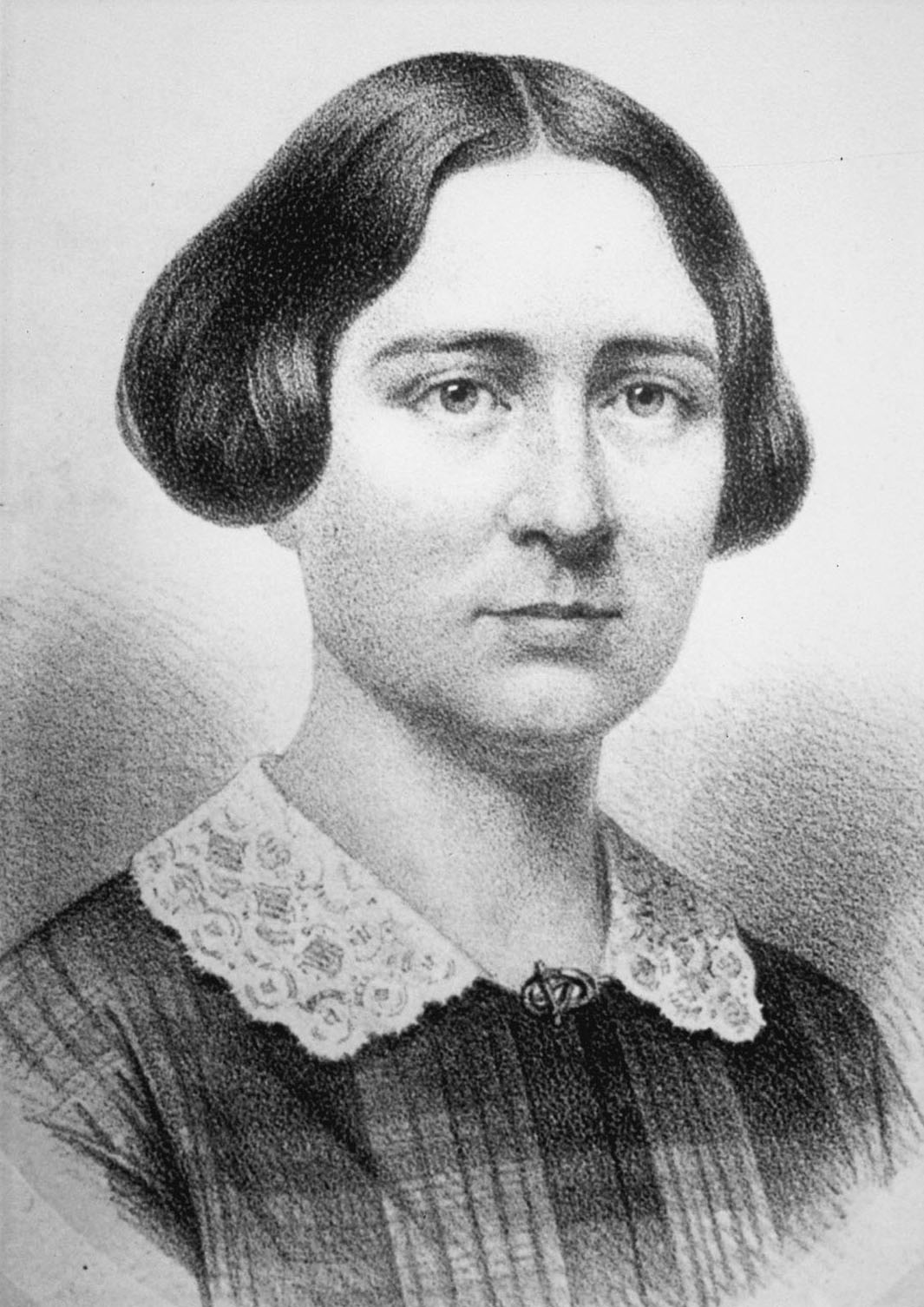

LUCY STONE.

NEW YORK INFIRMARY BUILDING AT THE CORNER OF BLEECKER AND CROSBY STREETS.

Three years later Henry watched Stone speak at antislavery meetings in New York and Boston, and though he balked at her Bloomer costume, he was smitten. “I decidedly prefer her to any lady I ever met,” he told Sam. No matter that this lady saw the institution of marriage as another form of bondage, in which a woman’s right to personhood and property was erased. In Lucy Stone, Henry had found a woman he could admire as profoundly as he admired his sisters.

A lifetime with those unbending sisters served him well in his ardent, dogged pursuit. His first step was a letter of recommendation from his father’s old friend Garrison, proving his abolitionist bona fides. Then he set out for the town of West Brookfield, Massachusetts, where the itinerant activist had paused for a visit to her family. Arriving at the Stone farm unannounced, Henry found his beloved standing on the kitchen table, whitewashing the ceiling. She declined his offer of help. Undeterred, he waited for her to finish and spent the afternoon walking at her side.

On his way home to Cincinnati, he sent her two books: a volume of Plato and Elizabeth’s The Laws of Life, the collection of lectures she had published a year earlier. How better to demonstrate his commitment to pioneering women? “I think you will like [Elizabeth’s] lectures very much,” he told Stone. Their courtship would continue for two years, while Henry tried to convince her that marriage need not be a prison. “If both parties cannot study more, think more, feel more, talk more & work more than they could alone,” he declared, “I will remain an old bachelor & adopt a Newfoundland dog or a terrier as an object of affection.”

Henry put himself at Stone’s service, helping to arrange western speaking engagements and welcoming her to the Blackwell home in Walnut Hills every time she traveled within range of Cincinnati. He expanded his reforming energies to include women’s rights and even made his first feminist speech, at the fourth National Woman’s Rights Convention in Cleveland. But the turning point came in the fall of 1854. The Supreme Court of Ohio had ruled that any slave who entered the state—even if traveling with their master—had the right to freedom upon request. At an antislavery meeting just outside Cincinnati, Henry and the other attendees learned that a train would soon be passing through, carrying a Tennessee couple accompanied by an enslaved girl. Henry headed a party that boarded the train, asked the eight-year-old girl if she wanted to be free, and when she said yes, removed her forcibly from her owners.

For weeks afterward, Kentuckians stopped by Henry’s store to stare at his face. A bounty of ten thousand dollars had been placed on his head across the river, and they wanted to make sure they recognized him if he crossed over. Gossip circulated that Henry had assaulted the white woman on the train. While he and his associates celebrated the girl’s liberation, others saw it as an act of theft. Henry himself was somewhat startled at his own temerity and dismayed at the dent his activism put in his hardware business, none too robust to begin with.

But Lucy Stone was thrilled. “I am very glad and proud too, dear Harry of the part you took in that rescue,” she wrote. “I exceedingly desire true relations for both of us.” Perhaps this impulsive, devoted young man really could share her life without compromising her ideals. Within two months, they were engaged. Henry assured her that he would never dictate the disposition of her earnings, the location of their residence, or the nature of her role as his wife. He also assuaged qualms she would not discuss in a letter: “You shall choose when, where & how often you shall become a mother,” he wrote.

Henry did not relax his astounding egalitarian ardor after his beloved said yes. “Lucy, I wish I could take the position of the wife under the law & give you that of a husband,” he wrote. Even before their engagement was official, he had made her a second, more extraordinary proposal: at their wedding, he would read a public protest against the laws that deprived married women of their rights. “I wish, as a husband, to renounce all the privileges which the law confers upon me, which are not strictly mutual,” he told her. “Help me to draw one up.”

The reaction of his sisters to the engagement of their liveliest brother was mixed. Elizabeth, whose opinion Henry prized most, reserved judgment. Miss Stone came from the tribe of woman suffrage advocates she had always disdained. “We view life from such different sides,” she hedged to Henry. “I thought discussion would be unavailing until personal affection had linked us together.” To Emily, Elizabeth worried that Henry’s adoration of this outspoken woman was a sign of his “morbid craving for distinction”—an ironic projection of her own hunger for recognition, compounded by the irritating sense that she was rapidly losing influence over her younger brother. “We must absolutely take the brightest view we can,” she wrote with a sigh, “as it seems to be inevitable, and if Lucy will soften her heresies, it may be a very happy union.” Emily was similarly cautious. “I hope that intercourse with our family may induce her to lay aside some of the ultra peculiarities that are so disagreeable to us,” she wrote back, wary of Stone’s exhibitionist extremism. “Certainly we will not allow it to break the strong feeling that has always existed among us if possible.”

The nine Blackwell siblings now ranged in age from twenty-two to nearly forty; it was hard to imagine opening their circle to a stranger for the first time. Anna, having renounced America permanently, wrote a screed expressing shock that Henry planned to marry an American—which he, in a moment of Blackwellian blindness to his fiancée’s feelings, blithely forwarded to Stone. But the family members still in Walnut Hills warmed to their future sister-in-law with each of her visits. “Sam says she is a most pleasant companion and very brilliant in conversation,” Marian reported. “Ellen loves her heartily & says she belongs to us by nature. Mother cannot help liking her in spite of her dreadful heresies, and George in his cautious critical way remarks that his only objection is to her ultraism.” Stone’s feminism was fine, her abolitionist opinions all to the good, but the Blackwells had always stopped short of “ultra”-anything. They might have embraced ideas toward the radical end of the political spectrum, but they insisted upon a decorum that Stone, in their eyes, had abandoned the first time she wore bloomers in public.

Henry, guileless as always, sent a draft of his marriage protest to Elizabeth and asked for her comments. “She has very good taste,” he assured Lucy, “& may make some suggestions of value.” He had not shared a roof with his sister in nearly a decade; perhaps he had forgotten her horror of airing private matters in public, and her bluntness when she thought he was wrong. “I protest against a protest,” she snapped in response, “and my short answer to ‘Why?’ would be, it’s foolish, in bad taste.” Henry’s intention of making a political statement at his own wedding she condemned as “vulgar vanity.” Marriage was an intimate act, she insisted. “Do not take the human nature out of it, by crushing it with platforms and principles.” But even she could see that this time Henry would not be dissuaded. Having made her case against bad taste, she followed it with several paragraphs of detailed edits. The final draft of the protest incorporated most of them.

On May 1, 1855, with the sun barely up and the dew still wet on the Stone family’s fields, Henry Blackwell and Lucy Stone stood before the Unitarian minister Thomas Wentworth Higginson and recited their marriage vows, which conspicuously omitted the word obey. A moment earlier Henry had read their protest, declaring that “this act on our part implies no sanction of, nor promise of voluntary obedience to such of the present laws of marriage, as refuse to recognize the wife as an independent, rational being, while they confer upon the husband an injurious and unnatural superiority.” Newspapers across the country reprinted it.

The bride wore a silk dress in the dusky shade known as “ashes of roses.” Though she would make history by continuing to use her maiden name after the wedding, in a letter to her closest friend she described the event as “putting Lucy Stone to death.” Her love for Henry was not in question, but her continuing uncertainty about the institution of marriage gave her a migraine on her wedding day.

The friend to whom Lucy Stone had written of her wedding with such black humor was a woman named Antoinette Brown. They had met a decade earlier as students at Oberlin, where Brown—seven years younger—had been warned upon arrival that Stone was “a young woman of strange and dangerous opinions.” Brown, possessed of opinions of her own, immediately sought her out. The two became passionate allies, often sharing a bed to continue their debates long into the night. Though Brown held less militant views than Stone on abolition, religion, and fashion, her belief in women’s equality was just as bold. Her lifelong ambition was to preach, and in the fall of 1853 she became the pastor of a tiny Congregational church in South Butler, New York—the first woman in America to be ordained as a minister. Henry had tried to persuade her to officiate at his wedding to Lucy.

ANTOINETTE BROWN, LATER BLACKWELL.

COURTESY SCHLESINGER LIBRARY, RADCLIFFE INSTITUTE, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

Henry embraced his Lucy’s dearest friend as another sister, then strove to make her just that. When Sam passed near South Butler on a trip from Cincinnati to Boston, Henry encouraged his brother to pay a call. Sam did not regret the detour. “I forgot my drenched boots and the rain and wind without while busily talking with her for 3 hours,” he recorded. “She seems to me to be a lady of judgment, very kind disposition and with the best principles and high aims,” he continued. “I enjoyed the visit exceedingly.”

Even as she won her own pulpit, Brown had begun to question the faith that required her to threaten the unconverted with hellfire, or condemn an unmarried woman who bore a child. Before a year was out, she left her congregation and joined her friend Lucy as a more secular kind of preacher. Like Lucy, when in Cincinnati she stayed with the Blackwells. And Sam, following Henry’s example, began the patient process of convincing “Nettie” that marriage and women’s equality were not incompatible. By Christmas 1855, Sam was able to write, “The love of her whom I love best on earth, though long withheld, is now wholly mine.” Nettie, having learned from Lucy of the Blackwells’ penchant for oversharing, gently cautioned her fiancé against forwarding her letters to his sisters. “They are for you, Sam dear, and full of haste, bad spelling, and confidences,” she told him. “Elizabeth can easily get acquainted for herself.”

Sam Blackwell and Antoinette Brown were married at her home in Henrietta, New York, on January 24, 1856. Sam borrowed Henry’s white wedding vest, though he preferred his own sober black coat to Henry’s dashing mulberry one. The wedding was less freighted with politics than Henry and Lucy’s, though Sam and Nettie declared themselves joint owners of any property. The officiant was Nettie’s magistrate father, and the event was sealed with “spirited miscellaneous kissing.” Lucy sent her congratulations, joking that Sam “alone of all men in the world has a Divine wife.”

The unmarried Blackwells were not the only ones ambivalent about these two weddings. Susan B. Anthony, who felt a sisterhood with both brides, scolded each of them for leaving her to work alone. Lucy, resolutely denying her own marriage misgivings, scolded her back. “You are a little wretch to even intimate that we are nothing now,” she wrote to Anthony. “Let me tell you as a secret that if you are ever married, you will find that there is just as much of you, as before.” Though both Lucy and Nettie would struggle to balance work with family, in Henry and Sam they had found men unusually well suited for the new role of feminist husband. The two brothers had been supporting professional women, emotionally and financially, since their teens. “I wish we had another brother for you, Susan,” Lucy teased. “Would we not have a grand household then?” But Howard had moved to England, and George was only twenty-three.

Henry and Sam’s marriages might have felt like a threat to the Blackwells’ clannish bonds, but the addition of Lucy and Nettie actually brought the family closer, at least geographically. Neither sister-in-law considered Cincinnati a convenient base for a lecturing life. Meanwhile Elizabeth and Marian had more space in New York than they needed—even with the addition of Kitty and the return of Marie Zakrzewska with her medical degree. By the end of 1856, Henry and Sam had sold their business and packed up their mother, and nearly all the Blackwells currently on the American side of the Atlantic converged at the house on Fifteenth Street.

Kitty goggled in amazement one autumn evening as fifteen carts pulled up in front of the house, bringing all the Blackwell possessions from Walnut Hills, including the piano and a tin box containing Hannah Blackwell’s precious wedding china. The house was suddenly filled to overflowing. Before long, Sam and Henry would establish new households across the Hudson in New Jersey; for now, though, Elizabeth’s home was a perfect place for the arrival of the newest Blackwell of all.

Kitty was on her way to bed one chilly night when she met Dr. Zak coming downstairs. “Would you like to see a baby?” Zakrzewska asked.

“Yes!” Kitty gasped. “Where did it come from?”

“It came out of a cabbage,” Zakrzewska told her, choosing to defer the start of Kitty’s health education.

“Nothing so nice as a baby ever came out of a cabbage!” the child retorted, rushing upstairs. But there on a pillow in front of the fire was a tiny infant, and Sam was crying out “Don’t you step on my baby!”

On November 7, 1856, Dr. Elizabeth and Dr. Zak had attended the birth of Nettie and Sam’s daughter, a difficult breech delivery eased by the use of James Young Simpson’s discovery, chloroform. “Thanks to our judicious doctors and to our Heavenly Father, all is well with both my Nettie and our tiny,” Sam wrote with relief. Two days later the extended clan gathered at Nettie’s bedside while Sam read out a list of girls’ names. (Nettie was either too generous or too exhausted to object to this being a group decision.) “I was in favor of her being called Mary,” Kitty remembered. But the Crimean War had just ended, and Florence Nightingale was now second only to Queen Victoria as the most famous woman in the world. Regardless of Aunt Elizabeth’s philosophical differences with her illustrious namesake, the first Blackwell of the next generation would be Florence. Nettie and Sam went on to raise five daughters, two of whom—though not Florence—earned medical degrees.

Little Floy was barely two weeks old when one more Blackwell arrived at Fifteenth Street: Emily, home from Europe at last. After Edinburgh she had lingered for months in London, trapped by family drama: Marie’s convalescence and Kenyon’s ill health; cousin Sam’s ill-fated love for Bessie Parkes; business troubles that forced her brother Howard to seek employment in India. All these unlucky Blackwells had looked to Emily for strength—a new and not unwelcome role for the even-tempered sixth sibling. “I have experienced for the first time the strange triumphant happiness there is in standing firm in a storm supporting those who are weaker,” she wrote.

Meanwhile she had attracted respectful recognition in London—at St. Bartholomew’s, Clement Hue had praised her “ardent love of knowledge, her indefatigable zeal in the examination of disease, her sound judgment and kind feeling”—and had finally reached Paris, where she walked in Elizabeth’s footsteps, shadowing prominent surgeons, studying at La Maternité (without mishap) and even visiting Hippolyte Blot, now a father of two. She also came in for the same kind of snark Elizabeth had earlier endured. Punch had chuckled all over again, running a caricature of “Dr. Emily” as a mannish woman in bloomers, squinting diagnostically at a lapdog clutched by a wasp-waisted young maiden. “The surname of the lady is immaterial, and, moreover, it may be hoped, will speedily be exchanged for another,” the item read, “since if to be cherished in sickness is an important object in marriage, a wife who in her own person combines the physician with the nurse must be a treasure indeed.” The joke was too stale to sting.

Confident in her work, Emily could ignore her critics. “The European hospitals will never be closed to women again,” she told Elizabeth. “My studies here will do something to help others.” She was tempted to establish herself in Britain but understood the basic paradox: she was welcome precisely because the “old fogies” assumed that as soon as she completed her studies, she would leave.

Emily reached New York in time for the merriest Christmas the Blackwells had enjoyed in years. The oldest and youngest siblings were absent: Anna was writing chatty dispatches for American newspapers from Paris, Howard was on his way to Bombay, artistic Ellen was now studying painting in Europe with the likes of John Ruskin and Rosa Bonheur, and George was lingering in Cincinnati. Lucy was on the road as usual. But crammed together at Fifteenth Street, the rest of the reunited and expanded clan indulged in roast beef and plum pudding. After dinner, grandmother Hannah and steadfast Marian, Elizabeth and Dr. Zak and little Kitty, Sam and Nettie and baby Florence, Emily and Henry settled snugly in the parlor, singing favorite songs and reading aloud from Robert Browning’s latest volume of poetry, Men and Women. There was a satisfying sense of return from western exile and European experiments to a base from which to launch larger plans.

CARICATURE OF EMILY IN PUNCH, 1856.

COURTESY NEW YORK SOCIETY LIBRARY

Even from France, anti-American Anna could sense the consolidation. “As things have turned out, & the band being now increased by our very excellent and welcome new sisters, I can no longer even wish you all to return,” she wrote with resignation, “but earnestly hope, on the contrary, that you may now really take root.”

* Clark studied successfully in Paris. On the voyage over, she made the acquaintance of Amos Binney, a recent widower. Within two years she married him and suspended her medical career; the couple had six children.