The story of Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell, pioneering and collaborating sister doctors, ends here. But each of their own stories, lived an ocean apart, continued for another forty years.

Elizabeth’s trajectory flattened in England. Her confidence that the rising generation of British medical women—led by Elizabeth Garrett and Sophia Jex-Blake—would welcome her as their mentor and colleague was misplaced. “Miss Garrett, though outwardly pleasant, is bristling with distrust and anxiety,” Elizabeth wrote to Emily from London. Over the next three years, Garrett would score a series of triumphs: the completion of her degree at the Sorbonne in 1870; the expansion of her Marylebone dispensary into the New Hospital for Women in 1872; the respect of physicians including Sir James Paget and the support of powerful philanthropists like Lord Shaftesbury; and the love of a Scottish shipping magnate, James Skelton Anderson, who not only approved of his bride’s career but bought her a carriage as a wedding gift to facilitate it. She had also learned her predecessor’s lesson—to hold other women at arm’s length, lest they reflect poorly on herself—only too well.

Sophia Jex-Blake was achieving a different sort of recognition. Refusing to seek her medical degree on the continent, she pursued admission at the University of Edinburgh. When the faculty insisted it could not allow such disruption for the sake of one woman, she recruited four more. On November 2, 1869—a year to the day after the opening of the Blackwells’ college—Jex-Blake’s group, which later grew to seven, became the first women to join a class of men at a British university. “I do indeed congratulate you undergraduates with all my heart,” Elizabeth wrote, beaming in their reflected light. “I feel as if I must come up to Edinburgh to see and bless the class!” But the Edinburgh Seven, as they became known, looked to Jex-Blake for leadership, and her take-no-prisoners style was the antithesis of Elizabeth’s measured, understated approach. Opposition in Edinburgh reached an ugly climax a year later when the women were pelted with garbage and epithets as they entered Surgeons’ Hall for an anatomy examination. The university eventually prevailed in preventing the women from completing their degrees, but the “Surgeons’ Hall Riot” generated enormous publicity for the cause of women in medicine. Though her confrontational approach alienated many—including Garrett Anderson—Jex-Blake led the way to the founding of the London School of Medicine for Women in 1874.

Elizabeth would serve in ceremonial roles as a consultant to Garrett Anderson’s hospital and on the faculty of Jex-Blake’s college, but these public endorsements masked an unsettling degree of personal antipathy. “Neither Miss Putnam, Miss Garrett, nor Miss Jex-Blake will ever be doctors, that as a woman I feel in the slightest degree proud of,” Elizabeth told Emily. “They are all hard, mannish, soulless; and though they are all doing excellent service as pioneers, and I am happy always to praise them . . . as women physicians such as we wish to see as a permanent and valuable feature of society, I think them not only useless but objectionable.” Such women physicians as Elizabeth wished to see were formed in her own image, devoted to health education rather than clinical practice, and inspired by right living rather than scientific advancement. It did not help that the British often confused her with another notable American doctor, Mary Walker, who had served as both a surgeon and a spy during the Civil War, spent months in a Confederate prison, and received the Medal of Honor. Even more memorable than Walker’s swashbuckling deeds was her personal style—she cut her hair short and wore trousers and frock coats. “I could not have imagined how very wide-spread and profound a mischief that little humbug could have done,” Elizabeth complained bitterly. “I am constantly addressed by her name, in mistake.”

Elizabeth found herself companionless, especially when the Bodichons decamped to Algiers and Barbara’s lively intellectual circle disbanded. She missed Kitty, who had grown from daughter-servant into something more like the proverbial angel in the house. “You can help me so much by taking charge of all my things and telling where they are and reading and occasionally stitching for me and doing errands and keeping my rooms in first rate order and above all loving me very much,” Elizabeth wrote to her in a plaintive rush. Kitty, deeply attached to Henry and Lucy’s daughter Alice, was quietly devastated to leave America behind, but her first loyalty was to Elizabeth; a year after her departure, she joined her in London.

Elizabeth might have spent her life fighting to open a profession to women, but she made it clear that neither career nor marriage was an option for Kitty, who remained suspended outside class or category—a young woman prematurely old, with graying hair, weak eyesight, and compromised hearing. Perhaps to compensate for the life Kitty had been denied, Elizabeth arranged to foster a baby in the fall of 1870, just as Kitty joined her in London. The child—the illegitimate son of the sculptor Susan Durant, a well-connected acquaintance—would be Kitty’s joy for the two years he remained with them.

Bolstered by Kitty’s generous steadfastness—as Alice would later say, Kitty “fitted herself into all Dr. Elizabeth’s angles like an eiderdown quilt”—Elizabeth continued her public quest. Medicine had always been just a pathway toward a morally perfect world, and the world remained far from perfect. She might be the only woman on the British Medical Register, but she had little success—or even interest—in attracting patients. She invested more active energy in the formation, in 1871, of the National Health Society, an organization devoted to the promotion of sanitary practice. Its motto—“Prevention is better than cure”—set hygiene firmly above the arts of diagnosis, pharmacology, and surgery. Over the next three decades, Elizabeth skipped from one cause to the next, always happiest when leading the way toward a better world. Her days were full of committee meetings and long stretches at her writing desk, churning out pamphlets and articles for publication. And though she was no longer spending much time healing the human body, she was no less preoccupied with it. As a physician and a moralist, she saw it as her responsibility to address the corrupting influence of sex.

Elizabeth had arrived in London days before the passage of the third and final Contagious Diseases Act, a measure—intended to curb the rampant spread of syphilis, especially in the military—that inflamed reform-minded women across Britain. The acts placed the burden of public health not on the soldier, whose need for sex was considered natural, but on the prostitute, who could now be arrested, forcibly examined, and confined to hospital if she was found to be infected. Elizabeth was outraged twice over: Not only did the law hold men and women to wildly different standards of sexual behavior, it also failed to condemn the evil of prostitution, punishing its victims instead of eliminating its causes. After her sojourns on the syphilis ward in Philadelphia and among the indigent women of Paris, London, and New York, Elizabeth understood how promiscuity and poverty converged in “that direful purchase of women which is really the greatest obstacle to the progress of the race.” She would leave the issue of eradicating poverty to others, but she was determined to make war on promiscuity. The repeal of the Contagious Diseases Acts became a clearly defined battle.

In the world Elizabeth envisioned, children would learn to venerate chastity at their mother’s knee, growing into men and women who honored the sanctity of procreation. Sanctity, indeed, had eclipsed science in the formulation of her opinions. Louis Pasteur’s recent experiments confirming the concept of germ theory had not yet convinced the general public, including Elizabeth, who could not embrace the idea that amoral microbes might be responsible for disease. Germ theory detached health from virtue—but for Elizabeth the two were inseparable. As a student she had written that ship fever found its victims among the fearful; now she refused to relinquish the conviction that venereal disease was caused by licentious behavior. In order to break the cycle of depravity, it was critical that parents teach the paramount importance of sexual propriety. And therein lay a paradox: in order to promote purity, Elizabeth insisted that parents should talk to their children about sex.

The book she eventually wrote on the topic—Counsel to Parents on the Moral Education of their Children in Relation to Sex—had nothing to do with the reproductive anatomy, though its subject remained incendiary enough that the publisher marketed it as a medical text. Her point was simply that men and women needed to live according to the same sexual standards, prizing the “exquisite spiritual joys” of marital intercourse over the “slavery of lust,” and teaching their children to understand and value the difference. Though Counsel to Parents did touch upon the dangers of autoerotic “self abuse,” its content was otherwise remarkably innocuous. “It might almost be read aloud in mixed company,” Emily wrote, shaking her head at the delicate sensibilities of British publishers. The book, released in 1879, would become the most widely read of Elizabeth’s works.

For nearly ten years, Elizabeth moved restlessly, with Kitty dutifully packing and unpacking in each new lodging, nursing her guardian through repeated attacks of undefined gastric illness, and accompanying her on extended convalescent trips to Europe. It became clear that London was not a healthy home for either of them, and with Elizabeth employing her pen far more than her stethoscope, they had no reason to stay. They settled at last in the seaside town of Hastings, in a trim brick cottage known as Rock House, perched on the edge of the English Channel and close enough to London that Elizabeth could remain active in organizations including the Social Purity Alliance, the National Vigilance Association, and the Moral Reform Union, all of them devoted to the cause of upright sexual conduct. Eventually Anna and Marian would join Elizabeth in Hastings, in a double house with two entrances that allowed them both proximity and distance. The Blackwells, to the end, loved and annoyed each other in equal measure.

Though Elizabeth’s primary message was one of chaste restraint, emphasizing the virtuous influence of wives and mothers in elevating the baser instincts of husbands and sons, she made detours into more eyebrow-raising areas, using her medical credentials to deflect criticism. In a pamphlet entitled The Human Element in Sex, she declared it “a well-established fact” that for happily married women, “increasing physical satisfaction attaches to the ultimate physical expression of love.” Furthermore, she insisted, “a repose and general well-being results from this natural occasional intercourse, whilst the total deprivation of it produces irritability.” It’s tempting to see this as a bracingly direct statement about female libido, but Elizabeth’s point reached straight back to the antique orthodoxy of Hippocrates and Galen. Furor uterinus, wandering womb, hysteria, nymphomania: since the dawn of medicine, men had been blaming female ailments on the unsatisfied uterus. “Let her marry, and the sickness will disappear,” went the ancient adage. In this as elsewhere, Elizabeth did not include herself among the women she counseled. She never ascribed her own irritability to her unmarried state, and never acknowledged that her authority on the health benefits of wifely sex might be questionable.

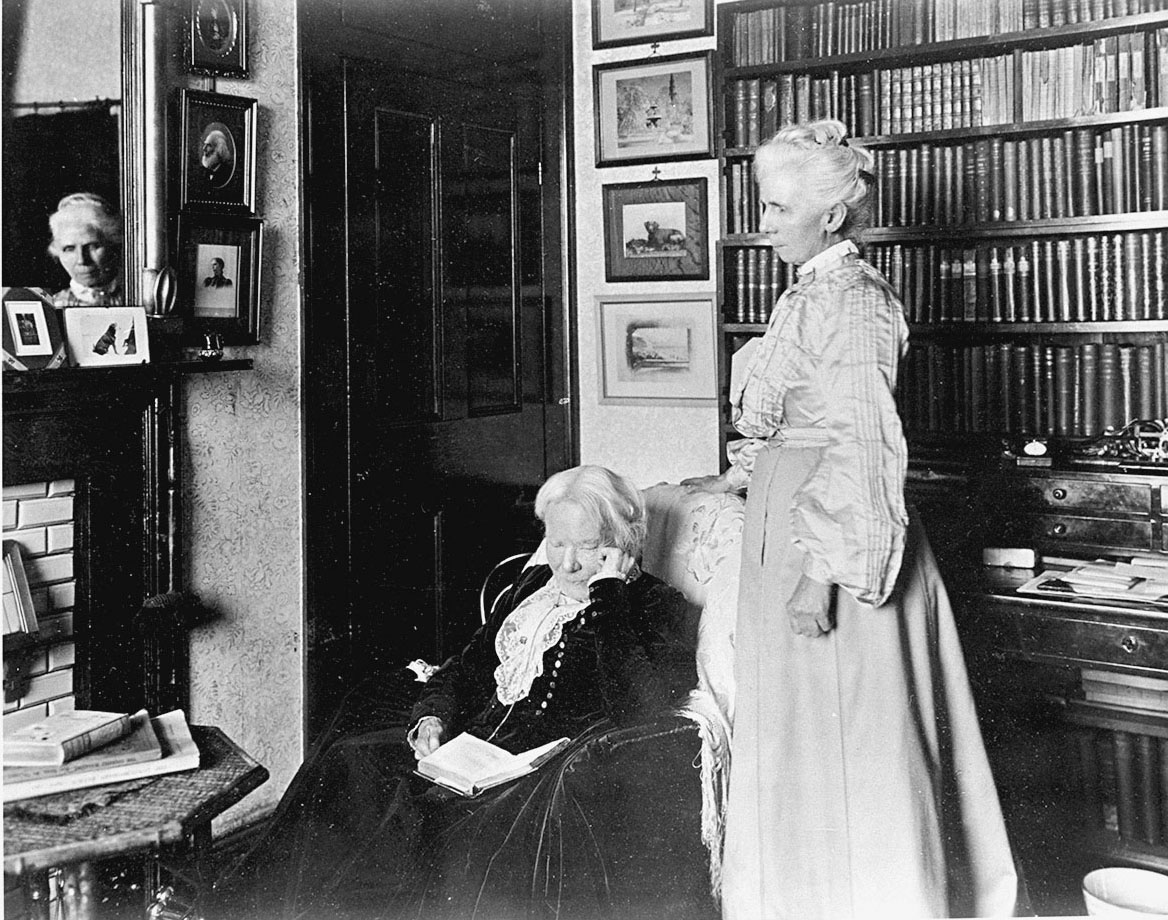

ELIZABETH AND KITTY AT ROCK HOUSE, HASTINGS, CIRCA 1905.

COURTESY SCHLESINGER LIBRARY, RADCLIFFE INSTITUTE, HARVARD UNIVERSITY

Though she endorsed the good-wife-wise-mother ideal, Elizabeth’s work among the poor had made it obvious that there was such a thing as too many children, a point she made in a speech entitled “How to Keep a Household in Health,” delivered just after her return to England. Procreation, she declared, “is largely under the control of established physiological laws, which should be known to parents.” Critics assumed she was endorsing artificial contraception—in the form of condoms (by this time made from rubber as well as animal intestine) or vinegar-soaked sponges—but to Elizabeth, protected sex was just as degenerate as masturbation. The only moral way to limit family size, in her view, was to restrict intercourse to the infertile days of a woman’s menstrual cycle. “From the outset of marriage the wife must determine the times of union,” Elizabeth later wrote. “Through the guidance of sexual intercourse by the law of the female constitution, the increase of the race will be in accordance with reason.” Her serene confidence that a righteous woman could regulate her husband’s sexual needs remained, like much of Elizabeth’s thinking, on a level too idealized for most flawed humans to find useful. Interestingly, in the same pamphlet, she defined a problem few acknowledged: marital rape. “A man who commits rape in marriage is even a meaner criminal than one who exposes himself to the just punishment which is attached to violence outside marriage,” she wrote. She offered no suggestions for women on how to avoid it.

Elizabeth’s moral crusading extended beyond the domestic sphere to the professional one. As her reform work led her further from the laboratory, she began to campaign against scientific advances she found morally questionable. Vaccination, for one. In New York. she had once lost an infant patient whose constitution was not strong enough to withstand the injection of the attenuated virus. “To a hygienic physician thoroughly believing in the beneficence of Nature’s laws,” she wrote in her memoir, “to have caused the death of a child by such means was a tremendous blow!” Wasn’t the first duty of a physician to do no harm? She developed a similar horror for vivisection. In England, she and Kitty grew attached to a series of canine companions, which explained her condemnation of experimentation on animals, but her objections increasingly included what she perceived as unnecessary surgery on human patients as well. For a woman who had come to prize prevention over cure, the idea of resorting to a scalpel seemed like mutilation, a presumptuous trespass on the divine design of the human body.

The one area in which Elizabeth was actively interested in scientific experimentation was, ironically, the realm of spiritualism. As she approached old age, and as new truths clashed unnervingly with her own understanding of the world, she may have craved the kind of existential comfort Anna had always sought in the supernatural. Though she had never shared Anna’s devoted faith in Mesmer’s magnetism or Baron du Potet’s séances—a faith her sister shared with many of the most prominent intellectuals of the era—she had never entirely dismissed it. Confidence in life after death, Elizabeth insisted as she entered her eighties, was “really of tremendous practical importance.” So she devised a plan: she would write down specific memories and seal them away, and after her death her friends would convene to see if her spirit could convey the hidden information to them. She failed to muster much interest in her experiment but followed through with her end of it just in case: “My ‘Test’ is written and safely put away.”

From the beginning, Elizabeth had seen medicine as a tool for showing people how to live: first in terms of opening the profession to women, and later as a way of teaching hygiene, both physical and moral. The girl who had refused to admit when she was sick grew into a woman who refused to accept human imperfection. The quest to transcend it fueled her, but her determination often hardened into a rigidity that drove potential allies away. “Doubt is disease,” she had proclaimed, but to dismiss doubt was to reject all opinions other than one’s own. Her refusal to compromise was the key both to her achievement and to her chronic isolation. She had dreamed of living in her own communal phalanx, but she never found people perfect enough to join her there.

For Emily, the period following Elizabeth’s departure was not easy. In addition to overseeing the details of the infirmary and the college, she needed to reassure her board, staff, and faculty that Elizabeth’s indefinitely extended absence did not signal their imminent failure. In the brief calm after the college’s first commencement in the spring of 1870, she despaired at the prospect of another year alone. “I am utterly unwilling to be so overworked and harassed with detail,” she wrote to Elizabeth, “to live in the midst of students & patients—the interests of my practice and the school interfering & clashing, and my personal life entirely suppressed.” But she saw no alternative.

Soon afterward, in the heat of August, Hannah Blackwell died, her long decline accelerated at the end by gangrene in her foot. Emily, suspended uncomfortably between the roles of daughter and physician, bound Hannah’s jaw with a handkerchief for her laying out. “I cannot describe the shock it gave me to perform that last office,” she wrote to Elizabeth. “The visible family link seemed broken in her loss.” Though they had never provided her with much emotional support, Hannah and Elizabeth had been fixed stars for her to steer by, one the center of the family circle, the other the driving force of her career. Now one was dead and the other distant. As she reached her mid-forties, Emily began for the first time to make her own choices.

Coming to her aid at last was Mary Putnam, her graduation from the Sorbonne having been delayed by the impact of the Franco-Prussian War. Emily had yearned for a competent colleague who shared her commitment to rigorous medical education; Putnam, having triumphed in the vibrant academic atmosphere of Paris, was if anything a more demanding instructor than Emily. Appalled by the caliber of the students she found at the Woman’s Medical College, Putnam caused an uproar by immediately expanding the scope of the curriculum. “I do not know whether she can adapt herself to circumstances and learn to be a good teacher for an American class studying after American modes,” Emily worried. Putnam seemed equally doubtful, dashing off an aggrieved letter to Elizabeth in which she announced the “thorough contempt” in which she held her new students. From England, Elizabeth attempted to mediate, advising Putnam to take things slowly. “It is utterly impossible to attempt to teach unless you are thoroughly in accord with your pupils,” Elizabeth wrote. “Do, my dear Mary, be very prudent and patient!”

Mary Putnam Jacobi—as she was soon to be known after her marriage to the pioneering German-Jewish pediatrician Abraham Jacobi—would become both a passionate scientist and a highly respected physician: a practitioner like Emily rather than a proselytizer like Elizabeth. She stayed on as Emily’s colleague at the college, always pushing for higher standards, and she eventually created a dedicated children’s ward at the infirmary. She wrote scores of respected articles, including one—“The Question of Rest for Women During Menstruation”—that debunked the conventional wisdom and won Harvard’s Boylston Prize. She became the first female fellow of the New York Academy of Medicine in 1880. Nearly two decades after Elizabeth’s departure, having reached a professional height from which she could regard her former mentor as a peer, she addressed Elizabeth with characteristic candor. “It is your mind that conceived the idea of women physicians in modern life, and on a plane at which few have ever thought of it,” she wrote, giving Elizabeth her due. But: “You never really descended from your vision, into the sphere of practical life within which that vision, if anywhere, must be realized. You left that for others to do.”

With Putnam Jacobi and a growing cohort of promising students to help realize the vision, for the first time Emily had space to consider her own domestic happiness. She began to construct a new family for herself. In the fall of 1870, immediately following her mother’s death, she adopted a baby girl and named her Hannah—“Nannie” within the family. “She is a bright sociable affectionate little thing and a wonderful pet,” Emily wrote to Kitty. “She is not exactly a pretty child, but she has pretty eyes.” As an infant, Nannie slept in a nest of cushions on Emily’s examining table; as a curly-blond “chatterpye” toddler, she stood clutching the banister rails and watching the carriages roll by in the street when Emily returned at the end of the day. While Kitty never addressed her guardian as anything but Dr. Elizabeth, Nannie called Emily “Mama,” and as an older child, she signed her affectionate letters with rows of kisses. She would go on to marriage and motherhood and would delight Emily with a quartet of towheaded grandsons.

The youngest Blackwell sister, Ellen, who had shelved her painterly aspirations and now served as Emily’s rather haphazard housekeeper, also adopted a baby: Cornelia, or “Neenie.” Nannie and Neenie would grow up together, often left in Ellen’s charge when Emily was preoccupied at the infirmary and supported mostly by Emily when Ellen—who had a large-hearted but short-sighted habit of accumulating stray orphans—ran short of money.

A hospital was not a good place to raise children. Now that Emily had a child, she could justify a house of her own. In 1873 she moved to 53 East Twentieth Street, a few steps from Gramercy Park, with room for her office, a nursery for Nannie and Neenie, and accommodations for Ellen, Marian, and George. It was a profound relief to be able to leave the infirmary for a home at last. As the moving cart loaded with furnishings rumbled away toward Twentieth Street in the dusk, Emily paused for a moment on the hospital steps, remembering the day that she and Elizabeth had first mounted the brass plate with their two names beside the door. Now it would hang at the new address; even as Emily became head of her own household, Elizabeth’s presence persisted. But the quiet delight with which Emily described the smallest details of her new home was palpable. “They have put down in the hall a sort of oilcloth called Linoleum,” she wrote to Elizabeth. “Mine has a dark red brown ground with a small red & black figure, very neat and harmonious with the carpets.” She planned to invite Henry and Sam and their families for Christmas, reuniting all the siblings who remained in America.

George would soon find a wife—Lucy Stone’s niece, Emma—and start a family of his own; Ellen would escape the city to spend extended periods with Nannie and Neenie at Blackwell properties in the suburbs. But Emily was not alone for long. In 1870 a new student had arrived at the Woman’s Medical College. Elizabeth Cushier, ten years younger than Emily, had come to medicine late, constrained by the care of her younger siblings after the death of their mother. Having spent a disappointing term at Clemence Lozier’s New York Medical College for Women, she found the level of seriousness she sought at the “Blackwell college” under the tutelage of Emily and Mary Putnam Jacobi. Cushier received her degree in 1872, and with the exception of eighteen months of further study in Europe, she never again left Emily’s side. She became an accomplished gynecological surgeon—eventually bringing J. Marion Sims’s fistula repair technique to the infirmary—and taught both obstetrics and surgery at the college as the only female clinical professor. In Cushier, Emily recognized a kindred spirit: an independent woman who approached her responsibility both to her family and to her career with good-natured, unfussy pragmatism and skill. And even as she graduated from Emily’s student to her colleague and then her closest friend, Cushier preserved the deep respect she had initially felt for her first medical mentor.

In the fall of 1882, Elizabeth Cushier moved in with Emily on East Twentieth Street. In her relationship with this new Elizabeth—as senior rather than junior partner—Emily found a steady source of something that had always been scarce: contentment. The two women were as compatible sharing a home as they were sharing an operating theater, and Cushier’s sister Sophie became a more competent helpmeet than flighty Ellen had ever been. “You ought to have a partner like Dr Cushier,” Emily wrote jovially to her niece Alice, “who has just superintended the making of my cloth suit, as she was not content with the unaided efforts of my dressmaker.” Emily was even more admiring of Cushier’s facility with a surgical needle. The two doctors, swathed in blue and white pinafores—“like a butcher’s apron, but a little more dandy”—performed operations at the infirmary regularly, sometimes with a double row of students as an audience. “Dr Cushier is really a skillful surgeon,” Emily wrote, “and very ambitious in that line.” It was her highest praise.

Even the formidable Mary Putnam Jacobi approved. Cushier was “a remarkably lovely woman, spirited, unselfish, generous and intelligent,” she wrote to Elizabeth in England. “I do not know what Dr. Emily would do without her. She absolutely basks in her presence; and seems as if she had been waiting for her for a lifetime.” When Elizabeth—feeling displaced?—clucked over Emily’s isolation from the rest of the Blackwell clan, especially when Emily suffered a bout of ill health, her sister set her straight. “No one could be more kind, devoted, and helpful than Dr Cushier was,” Emily retorted. “There is not one of my own family who could or would have done so much for me.” Cushier, she told Elizabeth, “is like a younger sister or elder daughter to me.”

Emily’s partnership with Elizabeth Cushier was warmed by love. “The last days have been busy ones dearest,” Cushier wrote while Emily was visiting Henry and Lucy. In Emily’s absence, Cushier was not only managing their patients but also having the house painted and polished. “Much as I want to see you dear, I am not sorry you will not be here until next week, for I do not wish you to come into an unsettled house,” Cushier wrote. “By this time next week you will be quietly settled in just what will then be the nicest little house in the world & my own dear doctor what a happy winter we shall have! Shall we not?” They lived together for the last three decades of Emily’s life.

The years passed rhythmically, with hospital practice and college instruction punctuated by summer escapes, first to Henry Blackwell’s property on the south shore of Martha’s Vineyard, and later to Emily and Cushier’s own retreat at York Cliffs, on the coast of Maine. The infirmary and college prospered; in 1876 the hospital moved to new quarters on Livingston Place, on the edge of Stuyvesant Square Park, leaving more room for the college on Second Avenue, and in 1888 the college moved as well, around the corner from the hospital on East Fifteenth Street, to create a more compact campus for its students. The financial strains of the early days faded as generous patrons relieved Emily of the burden of fund-raising; there was even the beginning of an endowment. Two of Sam and Nettie’s daughters, Edith and Ethel, received medical diplomas under Aunt Emily’s supervision.

One April afternoon in 1897, Emily—in her seventies, but still serving as dean of the college—took the opportunity of a quiet Sunday to start a letter to Elizabeth. The city was on holiday; the distant sounds of a parade celebrating the completion of General Grant’s tomb filtered toward them from uptown. “The doorbell has rung but once today, an unheard of calm,” Emily wrote. It had been nearly half a century since her sister sat idle on University Place, wishing desperately for patients to arrive.

It was typical of Emily to bury catastrophe in the middle of home news and the weather. Days earlier a messenger had woken the household in the middle of the night: the college was on fire. Construction debris from the installation of a new boiler had ignited, and the flames had climbed an airshaft to the roof. The building was gutted, all its equipment lost. “On the top floor was a dissecting-room, in which there were several corpses, which were cremated,” the Tribune noted ghoulishly. But the infirmary next door was unharmed, and discipline among the resident staff was so strong that many of the patients slept through the emergency.

“We have taken the next house, and made the best arrangements we can,” Emily wrote. “We shall go to work at once to rebuild.” She had stood by the institution from the beginning; she would not abandon it now. Neither would her trustees, who immediately printed a new appeal. “Women students need as much space to work in and as good material to work with as men do,” the pamphlet insisted. It was in the interests of both skeptics and progressives that the college, “which represents the life work of Elizabeth and Emily Blackwell, is so equipped and endowed, and its standards kept so high, that its diploma represents the best that can be had in medical education.” In the name of both Blackwells, then—the long-absent symbol and the present and active leader—the college was rebuilt and expanded, welcoming an unusually large class the following year. What had once been dubbed “the woman doctors’ college”—“at first in derision, and, later, with respect,” noted The Sun—had achieved a reputation sturdy enough to survive the blaze.