Space and Movement in Philodemus’ De dis 3: an Anti-Aristotelian Account

Although Epicurus’ main work is entitled On Nature, according to him the main goal of the study of nature (φυσιολογία) is an ethical one. In fact, as he puts it, “if we were not troubled by our suspicions of the phenomena of the sky and about death, fearing that it concerns us, and also by our failure to grasp the limits of pains and desires, we should have no need of natural science” (KD 11). Given this subordination, it is evident, then, that in works about ethical topics physics would only be touched upon, if it had direct implications or offered solutions to a specific ethical problem. It is thus no surprise that there are very few references to physics in the ethical and aesthetic works by Philodemus and other later Epicureans. The area where ethics is most connected to physics is theology.221 In particular physics comes into play when we are dealing with the vexed question of the physical constitution of the Epicurean gods. The problem was already stated by Cicero (ND 1, 68): “suppose we allow that the gods are made of atoms; then it follows that they are not eternal”.

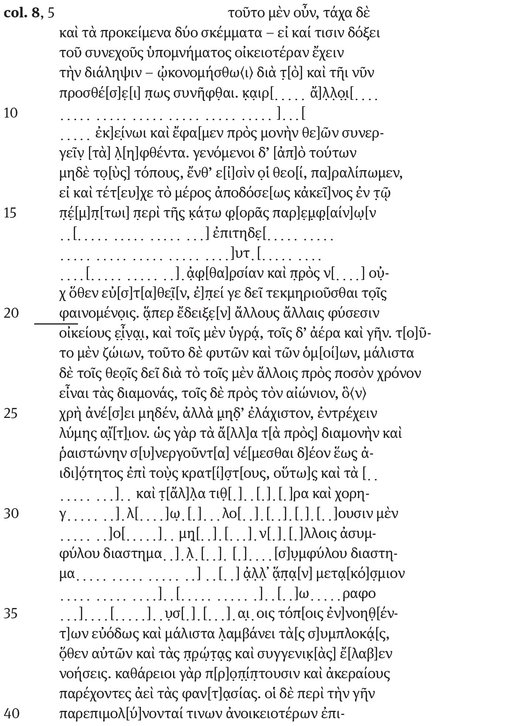

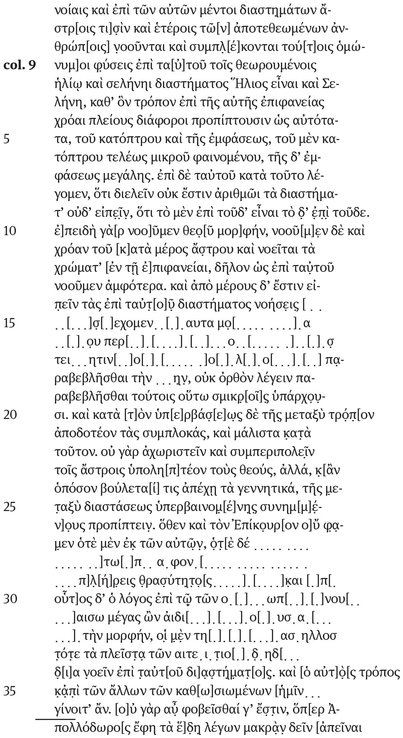

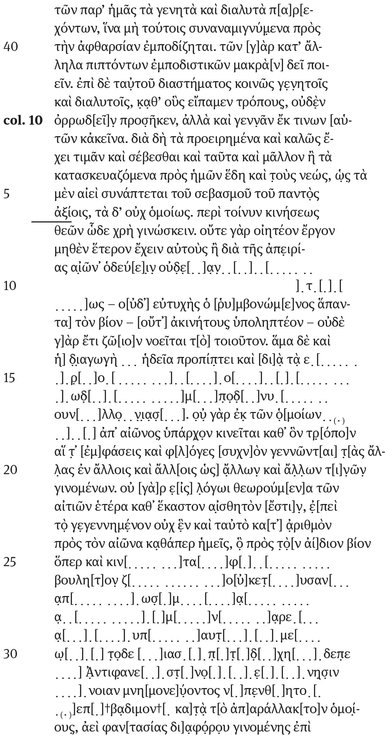

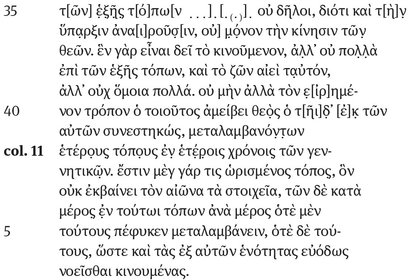

Physical problems continue to surface when Philodemus tries to provide a more detailed account of the life of the gods. In what follows I shall concentrate on two consecutive passages of his On Gods 3, the first discussing the space of the gods (col. 8, 5 – col. 10, 6), the second their locomotion (col. 10, 6 – col. 11, 7). These texts, I believe, will allow us to come to a first if preliminary assessment of Philodemus’ acquaintance with and application of physical doctrines of rival schools. My claim is that he is well aware of very specialized discussions and is even autonomously reworking and adapting them to the purpose of his own exposition. In particular I want to argue that Philodemus in this passage is referring to arguments and expressions used by Aristotle in his Metaphysics and meteorological works.

It is of course impossible to prove that Philodemus had first hand knowledge of these works. Anthologies, summaries and previous Epicurean writers always remain a possible source. A cumulative argument, however, does not seem out of place. In his aesthetic and rhetorical works Philodemus shows himself well acquainted with Peripatetic writings. The most striking example is his extensive use of Aristotle’s On Poets in the fourth book of his On Poems,222 Gigante in his Kepos e Peripatos lists references to Aristotle’s Politics and Rhetoric, as well as to his lost Gryllus, Eudemus, Synagogē technōn and On Philosophy.223 And moving closer to our field of investigation, we not only find Philodemus’ report about Epicurus’ studying of some of Aristotle’s works,224 but also a very likely quotation from Aristotle’s Metaphysics.225 Many passages in his On Sensations seem to answer on Aristotle’s De anima,226 and in On Signs Philodemus engages in arguments bearing on astronomical problems by trying to defend an affirmation endorsed by Epicurus, but previously ridiculed by Aristotle.227 There seems to be a general tendency among the Epicureans to adopt positions previously discarded by Aristotle (and/ or Plato) and structural parallels between the theology of Aristotle and of Epicurus have been stressed both in antiquity and modern times.228 But even in places were they agree on the results, they arrive there by very different arguments.229 Philodemus may thus be seen to follow in the tradition of Epicurus’ own polemics against Peripatetic doctrines,230 but some doctrinal innovations are very likely due to himself.231

In Philodemus’ On Gods several references to Aristotle have been detected. The detailed discussion of Peripatetic arguments on the fear of death in book 1 may be referred to the beginning of Aristotle’s Topica 3.232 In On Gods 3 Aristotle is named explicitly a couple of columns before our passage,233 and Arrighetti has already pointed out that Philodemus’ polemics concerning the motion of the gods are mainly directed against Aristotelian tenets.234

1 The text. Philodemus, On Gods 3, col. 8, 5 – col. 11, 7

The passage under examination consists of two chapters, each clearly marked as such in the papyrus by a coronis at its beginning and its end. The first chapter on the gods’ dwelling-places (col. 8, 5 – col. 10, 6) is introduced by some remarks about the disposition of the whole treatise and previous Epicurean treatments of the subject (col. 8, 5 – 20). The following parts appear to be more original. Philodemus sets out a biological/empirical principle which helps to determine the gods’ dwelling place. It is very likely that he goes on to identify this place with the intermundia which are mentioned in the next lacunose lines (col. 8, 20–34). After that he explains how wrong assumptions came about; in particular he offers a detailed account of the misleading concept formation about star gods (col. 8, 35 – col. 9, 36). The chapter closes with an appeal to Epicurean authority (Apollodorus of Athens, the predecessor of his teacher Zeno) and a generalising statement about the Epicurean view on the question. On the Epicurean account there is not only no danger for the gods’ blessedness in these dwelling places, but they even deserve more worship than our shrines and temples. The second chapter about the gods’ motion and rest (col. 10, 6–11, 7) takes up the wrong beliefs about star gods and starts with a refutation of the idea of endlessly revolving heavenly bodies. Neither restless motion nor complete immobility can be attributed to the gods (col. 10, 6 – 14). Philodemus also excludes another possibility, namely that the gods’ motion is only an illusion created by a succession of similar appearances at subsequent places (col. 10, 17 – 25). In the following heavily damaged lines he seems to come back to Epicurean authors, this time refuting a heterodox view held by Antiphanes (col. 10, 31 – 39). As in the preceding chapter, he closes with a summary of the Epicurean doctrine and an affirmation that with this explanation the gods’ motion is conceivable without any problem.

A common thematic nucleus in both chapters becomes clear if we set aside Philodemus’ auctorial remarks on disposition and his inner-Epicurean discussions: all passages that are not concerned with interpreting Epicurean authorities or dissidents treat physical arguments about the star gods. This is where Philodemus is most original and closest to Aristotle and we shall focus on these parts of the text. For convenience, however, I quote both chapters in full with a selective apparatus followed by an English translation:235

col. 8, 5 coronis 9  e.g. Essler 12

e.g. Essler 12  et

et  Philippson 14

Philippson 14  Hammerstaedt:

Hammerstaedt:  Henry 24

Henry 24  Scotti 25

Scotti 25  Hammerstaedt:

Hammerstaedt:  Scott:

Scott:  susp. Diels 26

susp. Diels 26  Diels 27-28

Diels 27-28  Diels 28

Diels 28  Scott:

Scott:  Diels 33

Diels 33  Diels 35-36

Diels 35-36

Diels:

Diels:  Arrighetti 37

Arrighetti 37  Diels 38 π[ροσπίπ]τουσιν Woodward 42-43

Diels 38 π[ροσπίπ]τουσιν Woodward 42-43  J. Delattre-Biencourt:

J. Delattre-Biencourt:  Scott

Scott  . Woodward

. Woodward

col. 9, 2  Liebich 4-5

Liebich 4-5  Woodward 10 suppl. Scott 12 suppl. Diels 14

Woodward 10 suppl. Scott 12 suppl. Diels 14  D. Delattre 15 init.

D. Delattre 15 init.  Janko 18

Janko 18  Scott:

Scott:  Scotti:

Scotti:  Purinton:

Purinton:  Janko 20 Woodward: ὑπ[έρ]βα[σιν] Scott: μεταξύ[τητι] Arrighetti 25 ὑπερβαινο[μένης] συνη[ Arrighetti: ὑπερβαίν[ων τοὺς] συνημ[έ|ν]ους Scotti: -βαίνε[ιν ἢ μ]ὴ Scott: ὑπ. κ(αὶ) μὴ Diels 26

Janko 20 Woodward: ὑπ[έρ]βα[σιν] Scott: μεταξύ[τητι] Arrighetti 25 ὑπερβαινο[μένης] συνη[ Arrighetti: ὑπερβαίν[ων τοὺς] συνημ[έ|ν]ους Scotti: -βαίνε[ιν ἢ μ]ὴ Scott: ὑπ. κ(αὶ) μὴ Diels 26  Scott [ο]ὐ Janko 27-28

Scott [ο]ὐ Janko 27-28  συνεσ]τῶ[τα suppl. Woodward 29

συνεσ]τῶ[τα suppl. Woodward 29  Karamanolis 30 Diels 33-34 possis [ἀί]|δ[ι]α νοεῖν vel

Karamanolis 30 Diels 33-34 possis [ἀί]|δ[ι]α νοεῖν vel  vel

vel  Scott 35

Scott 35  Henry:

Henry:  Woodward: [θεῶν Essler 36

Woodward: [θεῶν Essler 36  Scotti: [ε]ὖ Philippson

Scotti: [ε]ὖ Philippson  Scott 37

Scott 37  ἀπ]εῖ[ναι Scotti: μ. δεῖν [ποιεῖν] Scott: μ. δ. [ἀπέχειν] Diels

ἀπ]εῖ[ναι Scotti: μ. δεῖν [ποιεῖν] Scott: μ. δ. [ἀπέχειν] Diels

col. 10, 1-2 et  possis:

possis:  Hammerstaedt 4 fin.

Hammerstaedt 4 fin.  Scotti:

Scotti:  Diels 5

Diels 5

Arrighetti 6 coronis et dicolon ante

Arrighetti 6 coronis et dicolon ante  9

9  Henry 11

Henry 11  Henry

Henry  - Scotti 12 Scott 13

- Scotti 12 Scott 13  Diels, cetera Scott τ[ι] Scotti 14 πᾶσ᾿

Diels, cetera Scott τ[ι] Scotti 14 πᾶσ᾿  dub. Essler: πανηδεῖα Capasso 17-18 τῶν

dub. Essler: πανηδεῖα Capasso 17-18 τῶν  τὸ | θε]ῖο[ν] vel. [στοι|χε]ίω[ν] Essler: σ[τοιχεί|ων] Philippson 18

τὸ | θε]ῖο[ν] vel. [στοι|χε]ίω[ν] Essler: σ[τοιχεί|ων] Philippson 18  Scotti 19

Scotti 19  Diels:

Diels:  dub. Philippson 20

dub. Philippson 20  Scotti:

Scotti:  Diels:

Diels:  Scott 22 [ἔστι]ν dub. Essler: [χρόνον] Scott 23 Scott 24 ὃ Essler: ο〈ὐ〉 Philippson: ἕ〈ν〉 Diels 32

Scott 22 [ἔστι]ν dub. Essler: [χρόνον] Scott 23 Scott 24 ὃ Essler: ο〈ὐ〉 Philippson: ἕ〈ν〉 Diels 32  vel

vel  Essler 33 ἐπ[ι]

Essler 33 ἐπ[ι]  [ et μον[ήν] possis 35

[ et μον[ήν] possis 35  Philippson:

Philippson:  Henry 36 [οὐ μόν]ον Arrighetti: [καθό]σον Philippson 39 ε[ἰρ]ημ. Scotti 40 ὅ[στις ἐ]κ Scott: ὃ[ς οὐκ ἐ]κ Philippson:

Henry 36 [οὐ μόν]ον Arrighetti: [καθό]σον Philippson 39 ε[ἰρ]ημ. Scotti 40 ὅ[στις ἐ]κ Scott: ὃ[ς οὐκ ἐ]κ Philippson:  Purinton 41

Purinton 41  Scott: [καὶ τ]ῶν Scotti

Scott: [καὶ τ]ῶν Scotti

col. 11, 7 coronis

[col. 8] Let it be handled, what has been expounded about this question, as well as the two topics presently before us, even if some might think their analysis would be more suitably dealt with here than in the continuous treatise – because they are all somehow connected to the topic of the current addition. [This seems to be] the right moment to [address] other [questions]. (1 line missing) […] to Him (scil. Epicurus) and said that the things received contribute to the stability of the gods. Having stated this, let us not omit the places where the gods reside, although it happens that He (scil. Epicurus) has implicitly presented a part of the explanation in the fifth book (scil. of On Nature), talking about the motion downwards […] aptly […] imperishability and for (missing word) not and thus they enjoy tranquillity, because we have to infer from the appearances.

These (scil. the appearances) demonstrate that every nature has a different location suitable to it. To some it is water, to others air and earth. In one case for animals in another for plants and the like. But especially for the gods there has to (be a suitable location), due to the fact that, while all the others have their permanence for a certain time only, the gods have it for eternity. During this time they must not encounter even the slightest cause of nuisance because of remission (of happiness). For in the same way that one has to attribute to the mightiest as forever having the other things that contribute to permanence and easiness of life, also the […] unsuitable distance […] suitable distance […] every intermundium […] they (scil. the gods) are conceived without problems at […] places and (the mind) best grasps the connections (scil. between the invisible and the visible) from where it (scil. the mind) received the first, congenital ideas about them. For they appear as pure and always producing their impressions without contamination. The others, however, are sullied in the vicinity of the earth by conceptions of some less suitable things and they are conceived as being at the same distances as certain stars and others who have been deified by humans. And beings having the same name [col. 9] at the same distance as the sun and moon are observed, are conjoined with them to be Helios and Selene in the way that on the same surface several different colours appear, exactly as is the case with a mirror and its reflection. There the mirror appears perfectly small, but the reflection large. By ‘at the same distance’ we mean that it is not possible to distinguish the distances by number nor to say that one is at this (distance), the other at another. For since we conceive the form of a god and we conceive the colour of a particular star and the colours are conceived as being on the (same) surface, it is clear that we conceive both as being at the same (distance). And in part it is possible to say that the conceptions at the same distance […] have […] match with the […] it is not correct to say that the (missing word) is matched up with these as they are so small. And one must account for the connections according to transcendence of the intervening distance and most emphatically so. For one must not suppose that the gods are inseparable from and revolve together with the stars, but that, even if the things which generate (scil. the images of the gods) are as far away as anyone could wish, they transcend the intervening distance and appear in a constant stream. Thus we deny that Epicurus […] sometimes out of the same […]. […] full of rashness. […] the same is true for […] who is great, eternal […] the form […] then most of […] conceive of at the same distance. And the same explanation may hold in the case of the other things236 that have been worshipped.

For on the other hand it is impossible (scil. for the gods) to fear – as is stated by Apollodorus when he says that the dwellings have to be far away from the forces in our world that produce things subject to generation and dissolution, lest they become mixed up with these to the detriment of their imperishability. For we must make them out to be far from the hindering factors that clash against each other. However, being at the same distance from things subject to generation and dissolution in general, in the way we have said before, it is proper not to have any [col. 10] fear, but on the contrary it is befitting to generate the former (scil. the dwellings) also from some of their elements. In the view of what has been said before it is appropriate to honour and revere these (scil. the dwellings) as well, and more than the shrines and temples built by us, because they are always in connection with beings worthy of complete reverence, whereas our shrines and temples are not (in connection) in the same way.

As far as the movement of the gods is concerned, one has to understand it in the following way. For it should neither be thought that they (scil. the gods) have no other occupation than travelling forever through infinity, nor […] nor is he happy who is coiling his way all his life. Nor should it be thought that they are motionless. For such a thing is not even conceived as a living being. At the same time their way of life appears as pleasant and because of […]. For (the divinity), which exists from eternity being made up of similar [elements], is not moving in the way reflections or flames are often created one after the other, becoming a different (reflection or flame) in subsequent places. For in the case of objects perceived by the mind there can be no different cause for every single perception, because the result is not for all of its life numerically one and the same like us, which for eternal life […] which also movement […].

[…] Antiphanes […] bearing in mind […] indistinguishably similar, while an appearance different in every instance arises at the successive places […]. Are they not obviously abolishing even the existence of the gods, not only their movement? For what is moving has to be one, not many things at succeeding places (it moves through), and a living being has to be always the same, not many similar things. Nonetheless such a god, who thus consists of the same (scil. elements), changes (scil. his place) in the aforementioned way, while the generating materials successively [col. 11] take over different places at different times. For there is a circumscribed place, which the elements do not ever leave, but from the particular places within it is their nature to take over place after place – sometimes these, sometimes those – so that the units consisting of them are easily conceived as moving.

2 The gods’ dwelling place

Let us start with Philodemus’ guiding principle in establishing the gods’ dwelling place. He begins, in typical Epicurean fashion, with an appeal to phenomena. According to Philodemus we know from experience that every living being has a place suitable for its existence (col. 8, 20 – 23), and thus we may plausibly infer such a place for the gods as well. A similar cosmological argument is put forward in Cotta’s criticism of Epicurean theology:

As for locality, even the inanimate elements each have their own particular region: earth occupies the lowest place, water covers the earth, to air is assigned the upper realm, and the ethereal fires occupy the highest confines of all. Animals again are divided into those that live on land and those that live in the water, while a third class are amphibious and dwell in both regions.237

The examples used by Cotta and by Philodemus partly overlap (animals living in water, on land), and the point made is the same in both instances.238 Philippson suggested that both texts ultimately referred to Aristotle.239 However the idea of living beings and elements being divided across several places has a long tradition. 240

Yet there is another, biological version of this argument, which Cicero explicitly attributes to Aristotle. The context of this biological argument in Cicero is again theological. Its purpose is to demonstrate the existence of the star gods. Like the previous, physical principle it takes a start from the elements (earth, water and air) and their different capabilities not of sustaining but of generating living beings:

Since therefore some living creatures are born on the earth, others in the water and others in the air, it is absurd, so Aristotle holds, to suppose that no living animal is born in that element which is most adapted for the generation of living things.241

The Greek source of this reference is not extant.242 However, the same biological principle is still present in Aristotle’s and Theophrastus’ writings on animals and plants: in On Breathing Aristotle states his own principle of the proper dwelling-place being determined by each animal’s physical constitution:

One is bound to suppose that it is by necessity and for the sake of motion that such creatures are so made, just as there are many that are not so made; for some are made from a lager proportion of earth, such as the genus of plants, and others from water, such as the water animals; but of the winged and land animals some are made from air and some from fire. Each class has its sphere of life in the region appropriate (ἐν τοῖς οἰκεῖοις τόποις) to its preponderating element.243

He reaffirms this principle in a general sense: “any constitution is best preserved in its appropriate region”,244 and extends its function to reciprocity: “the material constitution of anything corresponds in fact to its environment”.245 The same principle is applied by Theophrastus in his Enquiry into Plants. I limit myself to quoting the beginning of book four, where he sets out to explain the geographical distribution of trees and plants special to particular regions and positions:

The differences between trees of the same kind have already been considered. Now all grow fairer and are more vigorous in their proper positions ( ); for wild, no less than cultivated trees, have each their own positions.246

); for wild, no less than cultivated trees, have each their own positions.246

Thus Cicero’s testimony and Aristotle’s own writings attest to two principles of the proper place well established and in wide use within the Peripatetic tradition: a physical one and a biological one. Aristotelian cosmology on the one hand is mainly built upon the physical principle which assigns to each element its proper place. In On the Heavens Aristotle uses it to prove that there can only be one world, not many (276b11 – 21) – thus excluding the existence of the intermundia, the realms of the Epicurean gods – and to define natural motion (279b2),247 which is the basis of his argument in favour of the divine nature of the heavenly spheres. On the other hand Philodemus (like Cicero’s spokesman) takes up Aristotle’s biological principle of the proper place to construct his cosmology.

I suggest that this move is Philodemus’ first step to undermine and demolish the Peripatetic position on the star gods. By exchanging one Aristotelian principle of proper place with the other he turns his opponent’s arguments against him. The passage in Philodemus and the Aristotelian view reported by Cicero bear the closest resemblance. They use the same examples. The elements, water, air and earth occur both in Aristotle and Philodemus, as do the corresponding living beings, plants and animals. Furthermore, the argument points in the same direction: Aristotle in Cicero is talking about the special environment most suited to ensuring the survival and growth of each living being, while Philodemus is concerned with finding this kind of place for the Epicurean gods. Thus he applies the principle which he shares with Aristotle, namely that each living being has a proper habitat suitable to sustaining its life, to the special case of the gods.

It has been a matter of debate whether the way of addressing the question of the gods’ dwelling place and the solution that they live in the intermundia, which was presumably stated in the following lines (cf. col. 8, 33 μετα[κό]σμιον), is Philodemus’ own invention or whether he was following one of his Epicurean predecessors. Our passage is the first attestation of  in this context. Later sources, however, attribute this view explicitly to Epicurus. Their statement is contested

by some scholars who believe that they are not reporting Epicurus’ own words and thoughts, but attributing to him interpretations by later Epicureans.248 I believe that, if not the result (i.e. the intermundia), at least Philodemus’ explanation for determining the gods’ dwelling place should most plausibly be credited to himself. As far as we can tell, he is not naming any authority on that matter and the biological principle of the proper place is first attested as a theological argument in Philodemus’ time (in his De dis 3 and Cicero’s ND 2). Strictly speaking, the same situation applies to the next passage on the star gods, although attempts have been made to identify events contemporary to Philodemus’ time.249

in this context. Later sources, however, attribute this view explicitly to Epicurus. Their statement is contested

by some scholars who believe that they are not reporting Epicurus’ own words and thoughts, but attributing to him interpretations by later Epicureans.248 I believe that, if not the result (i.e. the intermundia), at least Philodemus’ explanation for determining the gods’ dwelling place should most plausibly be credited to himself. As far as we can tell, he is not naming any authority on that matter and the biological principle of the proper place is first attested as a theological argument in Philodemus’ time (in his De dis 3 and Cicero’s ND 2). Strictly speaking, the same situation applies to the next passage on the star gods, although attempts have been made to identify events contemporary to Philodemus’ time.249

3 The refutation of the star gods

The main passages about the star gods are found in Aristotle’s Metaphysics and On the Heavens. Let us start with Aristotle’s definition of god: “We hold, then, that god is a living being, eternal, most good; and therefore life and a continuous eternal existence belong to god; for that is what god is”.250 Two of these divine properties are shared by the Epicurean gods: life and eternity. They will be at the basis of Philodemus’ argument. He is of course following a long tradition within the Epicurean school: the polemics against the star gods go back to Epicurus himself. 251 In fact Philodemus’ argument is twofold. On the one hand he quotes an Epicurean authority, Apollodorus of Athens, to show that the gods cannot be in direct contact with our world, because this would impair their eternal existence (col. 9, 36–42), but this only serves to round off his exposition. In the main part he is not arguing directly against the star gods – they had already been refuted by his masters252 – but instead he provides a physical explanation as to how these wrong assumptions about the divinity of the stars come about. Following the tradition of his school, Philodemus’ argumentation seems not only to rely on Epicurean principles, but also to make use of Aristotelian arguments by turning them against their author. His explanation draws an analogy between optical and intellectual perception to posit the case of an object which is entirely appearance (ἔμφασις). In case of the star gods, Philodemus claims they are mere reflections (ἐμφάσεις) of the real gods. As examples he chooses the sun and the moon, which are in turn identified with the divinities Helios and Selene:

And beings having the same name at the same distance as the sun and moon are observed, are conjoined with them to be Helios and Selene in the way that on the same surface several different colours appear, exactly as is the case with a mirror and its reflection (col. 8, 43 –col. 9, 5).

Philodemus’ whole construction is an analogy to Aristotle’s famous theory of the rainbow.253 We have his own description at the beginning of Meteor. 3, Seneca’s account (QN 1, 3 – 8) and a detailed summary in Aëtius (3, 5). All these sources attribute to Aristotle the main features of the optical phenomenon: imaginary existence (ἔμφασις), very small mirrors, the reflection of colour without shape. By these features Aristotle explains the rainbow as a special reflection of the sun in a cloud of raindrops without any proper existence and likewise Philodemus explains the imaginary star gods as a reflection of the real gods appearing at the same place as the heavenly bodies. In applying this explanation to the star gods Philodemus attains several goals: a) he provides a physical explanation of the common belief in the divine nature of heavenly bodies; b) he demonstrates these beliefs to be wrong because they are based on a wrong interpretation of sense perception; c) he again turns an Aristotelian argument against an Aristotelian doctrine.

The conclusion underlying Philodemus’ argument against the star gods is stated explicitly by Aëtius in regard to the rainbow: “of the things on high some … have real existence ( ) and others come about through appearance (κατ᾿ ἔμφασιν), lacking a real existence of their own … now the rainbow is according to appearance”.254 Seneca goes in the same direction:

“there is no actual substance in that reflecting cloud; it is no material body but an apparition, a likeness without reality”.255 Since both Seneca and Aëtius present this view together with the typical doctrine of visual rays, we may confidently accept it as Aristotelian.256 As Jaap Mansfeld puts it: “Aristotle seems to have been quite prominent and rather exceptional in claiming and arguing that rainbows and halos are optical phenomena, appearances”.257

) and others come about through appearance (κατ᾿ ἔμφασιν), lacking a real existence of their own … now the rainbow is according to appearance”.254 Seneca goes in the same direction:

“there is no actual substance in that reflecting cloud; it is no material body but an apparition, a likeness without reality”.255 Since both Seneca and Aëtius present this view together with the typical doctrine of visual rays, we may confidently accept it as Aristotelian.256 As Jaap Mansfeld puts it: “Aristotle seems to have been quite prominent and rather exceptional in claiming and arguing that rainbows and halos are optical phenomena, appearances”.257

Philodemus continues his explanation with more details. The divine images emitted by the gods from the intermundia seemingly originate from the stars themselves, because when these eidōla pass the outer rim of our universe, that is the sphere where the stars are attached, they lose the information about the distance travelled so far. In this way, when they are perceived by us, they give the impression of being emitted from the same distance as the eidōla from the stars and thus they seem to come from them. As a proof Philodemus adduces an optical phenomenon that shows exactly this characteristic of suppressing the distance between the emitter and another object on the way to the observer:

There the mirror appears perfectly small, but the reflection large. By ‘at the same distance’ we mean that it is not possible to distinguish the distances by number nor to say that one is at this (distance), the other at another. For since we conceive the form of a god and we conceive the colour of a particular star and the colours are conceived as being on the (same) surface, it is clear that we conceive both as being at the same (distance) (Phld. D. 3, col. 9, 5–13).

It is worth noting how Philodemus distinguishes between the form of the god (μορφή), his colour (χρόα) and the colours (χρώματα). This corresponds to Epicurus’ definition of optical perception in the Letter to Herodotus. According to that passage the sense of sight provides two pieces of information about the object: its form (μορφή) and its colour (χρῶμα, Epicur. Ep. Hdt., 49).258 In his comparison, then, Philodemus is making use of a special kind of mirror with two peculiarities: on the one hand it is only reflecting the colour of an object, not its size and form, and on the other hand it gives the impression that the object reflected is situated on the very surface of the mirror. In this way the distance between mirror and reflected object is suppressed, thus making the appearance of the mirror coincide with the appearance of the object.

This is the same optical mechanism Aristotle uses to explain the rainbow. He starts from the principle that very small mirrors would only reflect the colour (χρώματα) but not the size and form (σχήματα) of an object.259 The forming raindrops in a cloud of mist before the rain serve as small mirrors. They are each invisibly small, indivisible to our perception ( ), but together they form a continuous zone of reflection that creates one continuous appearance. However, unlike a normal mirror, each single mirror reflects only the colour of the sun, not its form and size:

), but together they form a continuous zone of reflection that creates one continuous appearance. However, unlike a normal mirror, each single mirror reflects only the colour of the sun, not its form and size:

Now it is obvious and has already been stated that a mirror of this kind renders the colour of an object only, but not its shape. Hence it follows that when it is on the point of raining and the air in the clouds is in process of forming into raindrops but the rain is not yet actually there, if the sun is opposite, or any other object bright enough to make the cloud a mirror and cause the sight to be reflected to the object then the reflection must render the colour of the object without its shape. Since each of the mirrors is so small as to be invisible and what we see is the continuous magnitude made up of them all, the reflection necessarily gives us a continuous magnitude made up of one colour; each of the mirrors contributing the same colour to the whole. We may deduce that since these conditions are realizable, there will be an appearance due to reflection whenever the sun and the cloud are related in the way described, and we are between them.260

Aristotle underlines the very small size of these reflecting drops several times (

, 374a33–34). Seneca provides a similar explanation as to how the many mirrors and reflections give one single appearance:261

, 374a33–34). Seneca provides a similar explanation as to how the many mirrors and reflections give one single appearance:261

Accordingly the countless drops carried down by the falling rain are so many mirrors and contain so many images of the sun. To the observer facing them these images appear confused, and the spaces between individual reflections cannot be discerned, since distance prevents them from being told apart. As a result, instead of individual images a single, confused image is visible from all of them.262

This drop theory seems to be typically Aristotelian.263 The only feature Philodemus has not taken over from him seems to be the theory of visual rays. In this respect he remains loyal to the Epicurean doctrine of the visual eidōla, but apart from that he fully applies Aristotle’s optical mechanism of the drop theory to his case. This is the reason for his insisting on the small size of the mirror (col. 9, 5–6: τοῦ

) and the distinction we noted before between the god’s shape and his colour. Thus I believe that here once again Philodemus is reusing and reworking concepts and explanations originally devised in the Peripatetic school.264 This time he turns them around, not to prove his case, but to explain his opponent’s error.

) and the distinction we noted before between the god’s shape and his colour. Thus I believe that here once again Philodemus is reusing and reworking concepts and explanations originally devised in the Peripatetic school.264 This time he turns them around, not to prove his case, but to explain his opponent’s error.

4 The motion of the gods

The star gods reappear in the next column at the beginning of Philodemus’ next chapter, on the motion of the gods. While Aristotle moves from the motion of the stars – viz. the star gods – to their proper place (Cael. 293a11 – 14), the Epicurean treatment follows the inverse order: both Cicero in his refutation of Epicurean theology and Philodemus start with the gods’ whereabouts and continue with their locomotion.265 The problem Philodemus will have to face, once he has accepted the principle of the proper place, is the same Aristotle discusses in On the Heavens: if we conclude that in order to preserve their everlasting nature the gods must reside in the place most suitable to them, can we ever conceive them to be moving, in so far as this implies leaving this very place and proceeding to another? Aristotle deals with this question in his discussion about the movement of his divine stars. In the light of Aristotle’s theory about the heavenly sphere that contains the divine stars in their proper place, as they revolve in constant motion around us, it becomes clear why Philodemus in between the traditional sequence of topics dealing with the gods’ dwelling place and their motion inserts his refutation of the star gods: apart from the Epicurean gods only these have ever been credited with fulfilling both conditions for divine existence, as they are the only bodies to be said a) to always reside in their proper place and b) to still be in motion. It is exactly these two qualities that Philodemus is trying to claim for the Epicurean gods, while at the same time he is attempting to deny the divine quality to their Peripatetic rivals.

In On the Heavens Aristotle introduces again the principle of the proper place, this time in a compromise version between the physical and the biological position. He holds that it is detrimental for every living being if its elements are not in their proper place:

Instances of loss of power in animals are all contrary to nature, e.g. old age and decay, and the reason for them is probably that the whole structure of an animal is composed of elements whose proper places are different; none of its parts is occupying its own place.266

It is clear then that neither the gods themselves as a whole nor their single elements must ever be in or come to a place not suitable to them. Aristotle solves the problem by introducing circular motion, thus making the stars move from one suitable place to another. In this way, they are constantly moving without ever leaving their proper place:

It (scil. the divine) is too in unceasing motion, as is reasonable; for things only cease moving when they arrive at their proper places, and for the body whose motion is circular the place where it ends is also the place where it begins.267

Some aspects of the underlying cosmology had already been attacked by previous Epicureans. For example the question of the movement or rest of the outer rim of the cosmos and the fixed stars is discussed in Epicurus’ Letter to Pythocles and by Lucretius. In these arguments, references to Aristotle’s On the Heavens and Theophrastus have been detected by Mansfeld.268 According to Aristotle we may infer the existence of imperishable beings from eternal spatial motions, as we observe them in the case of the universe turning round itself and in the case of the eternal motion of the fixed stars and planets. The basic tenet of this part of Peripatetic cosmology may be summarised as follows: “a body which moves in a circle is eternal and is never at rest”.269 Philodemus, following the Epicurean tradition, attacks the idea of the eternal and circular movement of the gods:

for it should neither be thought that they (scil. the gods) have no other occupation than travelling forever through infinity, nor […] nor is he happy who is coiling his way all his life. Nor should it be thought that they are motionless. For such a thing is not even conceived as a living being (col. 10, 7–13).

The argument against the eternal motion of the gods resorts to the notion of a god as a blessed and immortal living being ( ), but in the

second part it also takes in a biological perspective, which in turn is also found in Aristotle: the gods need to move in some way, because movement is a necessary property of a living being: “for the animal is sensible and cannot be defined without motion”.270

), but in the

second part it also takes in a biological perspective, which in turn is also found in Aristotle: the gods need to move in some way, because movement is a necessary property of a living being: “for the animal is sensible and cannot be defined without motion”.270

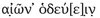

In addition I would like to consider another passage, from Aristotle’s On the Heavens, which may help explain a rare word in Philodemus. In fact, when talking about the eternal motion of the heavenly bodies, Philodemus describes the movement of the planets using the verb ῥυμβωνάω ‘to coil one’s way’. It is attested only in the ancient lexica by Hesychius, Photius, Suda and Zonaras and seems to denote the loops of the outer planets during the periods of retrograde motion.271 The parallel description of the everlasting movement of the universe is the juncture  ‘to travel eternally’ which apparently answers a specific passage in Aristotle’s On the Heavens. Its general context is very similar to Philodemus’ argument: there Aristotle is first describing the region outside our world, as Philodemus was dealing with the gods’ realms in the intermundia, and in a second step both Philodemus and Aristotle address the question of the gods’ motion. In between, however, Aristotle inserts an excursus on the definition and etymology of the αἰών. I suggest it was this passage that inspired Philodemus in the use of his metaphorical expression.

‘to travel eternally’ which apparently answers a specific passage in Aristotle’s On the Heavens. Its general context is very similar to Philodemus’ argument: there Aristotle is first describing the region outside our world, as Philodemus was dealing with the gods’ realms in the intermundia, and in a second step both Philodemus and Aristotle address the question of the gods’ motion. In between, however, Aristotle inserts an excursus on the definition and etymology of the αἰών. I suggest it was this passage that inspired Philodemus in the use of his metaphorical expression.

Changeless and impassive, they have uninterrupted enjoyment of the best and most independent life for the whole aeon of their existence. Indeed, our forefathers were inspiered when they made this word, aeon. The total time which circumscribes the length of life of every creature, and which cannot in nature be exceeded, they named the aeon of each. By the same analogy also the sum of existence of the whole heaven, the sum which includes all time even to infinity, is αἰών, taking the name from ἀεὶ εἶναι (‘to be everlastingly’), for it is immortal and divine.

And (according to the more popular philosophical works) the foremost and highest divinity must be … in unceasing motion, as is reasonable; for things only cease moving when they arrive at their proper places, and for the body whose motion is circular the place where it ends is also the place where it begins.272

My impression is then that both terms are intended to ridicule Aristotelian doctrine:  seems to compare the movement of the divine planets to the coiling of a serpent, while αἰῶν᾿ ὁδεύ[ε]ιν points to the tiresome aspect of a never ending march, which would be quite inappropriate for a blessed star god.

seems to compare the movement of the divine planets to the coiling of a serpent, while αἰῶν᾿ ὁδεύ[ε]ιν points to the tiresome aspect of a never ending march, which would be quite inappropriate for a blessed star god.

5 The perception of the moving gods

The next argument put forward by Philodemus is a crucial passage in Epicurean theology. For my present purpose, however, I am not going to discuss its implications on the problem of the physical constitution of the Epicurean gods.273 Instead I shall try to show its dependence on Aristotelian terminology and thought. Apart from the circular movement, Philodemus also denies another kind of movement to the gods: they are not moving by appearance in the way reflections or flames do, which are continuously created one after the other in subsequent places. In this case he seems in line with Aristotle’s description of the eternal gods: “All things which change have matter, but different things have different kinds; and of eternal things such as are not generable but are movable by locomotion have matter; matter, however, which admits not of generation, but of motion from one place to another”.274

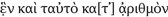

According to Philodemus the reason for this is that for objects perceived by the mind ( ) there can be no different cause (αἰτία) for every single perception of an object. Otherwise the object perceived would not be numerically one and the same (ἕν καὶ ταὐτὸ κατ᾿ ἀριθμόν, col. 10, 18–21).

) there can be no different cause (αἰτία) for every single perception of an object. Otherwise the object perceived would not be numerically one and the same (ἕν καὶ ταὐτὸ κατ᾿ ἀριθμόν, col. 10, 18–21).

The first thing to be noted is the concept of numerical identity. It takes up two definitions by Aristotle, the definition of the one, and the definition of the same. In his Metaphysics Aristotle distinguishes four cases of the ἕν:

Again, some things are one numerically, others formally, others generically, and others analogically; numerically, those whose matter is one; formally, those whose definition is one; generically, those which belong to the same category; and analogically, those which have the same relation as something else to some third object. In every case the latter types of unity are implied in the former: e.g., all things which are one numerically are also one formally, but not all which are one formally are one numerically.275

Our case is the first, the identity of substance. Likewise sameness is divided into three subcategories: something may be the same numerically, in form or in kind:

‘Identity’ has several meanings. (a) Sometimes we speak of it in respect of number. (b) We call a thing the same if it is one both in formula and in number, e.g., you are one with yourself both in form and in matter; and again (c) if the formula of the primary substance is one, e.g., equal straight lines are the same, and equal quadrilaterals with equal angles, and there are many more examples.276

From the Topics we learn that everything which is numerically one ( ) is also numerically the same (

) is also numerically the same ( ), but not vice versa.277 In De anima he denies numerical identity to anything that is perishable.278 With these definitions Aristotle investigates several problems, for example the question, whether the water of the sea remains always the same numerically or the same in its form:

), but not vice versa.277 In De anima he denies numerical identity to anything that is perishable.278 With these definitions Aristotle investigates several problems, for example the question, whether the water of the sea remains always the same numerically or the same in its form:

Does the sea always remain numerically one and consisting of the same parts, or is it, too, one in form and volume while its parts are in continual change, like air and sweet water and fire? All of these are in a constant state of change, but the form and the quantity of each of them are fixed, just as they are in the case of a flowing river or a burning flame.279

To illustrate the alternatives Aristotle puts forward two examples of objects that remain the same only in form, but not numerically. The first example, flowing

water in a river, might remind us of one theory about the physical constitution of the Epicurean gods. According to some scholars the gods consist of streams of images which flow together from various places. Their constitution is thus analogous to that of a waterfall. More interesting, however, is the second example, a stream of fire ( ). The same example is used by Philodemus and it is used in order to make the same point: the gods are not moving in the manner of reflections or flames ([ἐμ]φάσεις καὶ φ[λ]όγες, col. 10, 19), because the result would not be numerically one and the same (

). The same example is used by Philodemus and it is used in order to make the same point: the gods are not moving in the manner of reflections or flames ([ἐμ]φάσεις καὶ φ[λ]όγες, col. 10, 19), because the result would not be numerically one and the same ( , col. 10, 23). Since to the best of my knowledge there is no other parallel for this idea, it seems plausible that what Philodemus has in mind is the text of Aristotle’s Metaphysics here.

, col. 10, 23). Since to the best of my knowledge there is no other parallel for this idea, it seems plausible that what Philodemus has in mind is the text of Aristotle’s Metaphysics here.

To sum up: it is of course impossible to prove that Philodemus had direct knowledge of the Aristotelian works referred to in the course of my paper, namely his Metaphysics and meteorological writings.280 The arguments examined show however a strong familiarity both with the content and the terminology of these works. I believe that these two theological passages give us a rare glimpse on an aspect Philodemus does not betray in his other preserved writings: a sound training in physics and metaphysics, with a focus on Peripatetic doctrine. He was not only aware of his opponent’s views, but he was able to rework and recombine them for his own purpose. By substituting the definition of the proper place in Aristotle’s physics with the definition of the proper place in his biological writings, he paves the way for the idea of the intermundia as a safe residence for his gods. By transferring the Aristotelian drop theory of the rainbow to theology, he is able to explain the wrong beliefs in star gods, prominently held by the Peripatetics. He dwells on the paradox that arises when we impose Aristotle’s doctrine of divine motion on living beings and he uses Peripatetic terminology, concepts and examples to save his own gods from the mere imaginary existence he had previously assigned to the Aristotelian divinity. This might seem like an idiosyncratic theory of space, but his use of previous sources is certainly in line with the method of his master.281 After all, it is a piece of  whose value every Epicurean could acknowledge.

whose value every Epicurean could acknowledge.