NINETEEN ’83

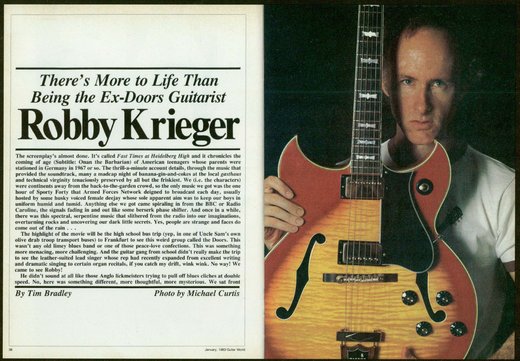

Robby Krieger details the origin of the Doors’ biggest hits,

Les Paul contemplates life as a one-armed bandit and

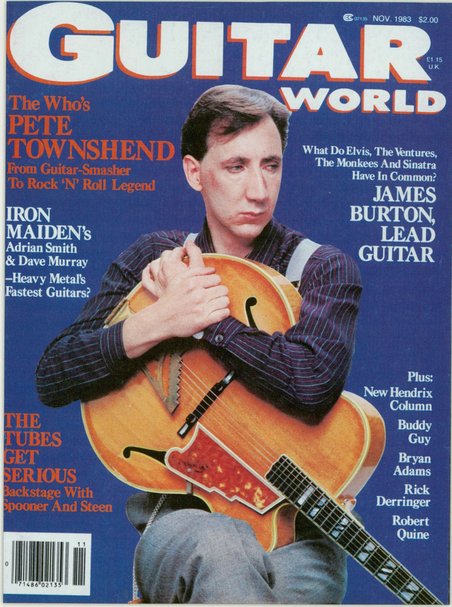

Pete Townshend gives birth to the “windmill.

Dear Guitar World,

By my calculations, approximately 3.5 percent of Guitar World is devoted to musically usable and worthwhile information. The rest is a mindless hodge-podge of equipment and rehashed anecdotes. Find some writers who can probe or some musicians who can articulate. Both would be great!

—Bob Chief

JANUARY Doors guitarist Bobby Krieger enters a new phase of his musical career, but happily reflects on his glorious past.

COVER STORY BY TIM BRADLEY PHOTO BY MICHAEL CURTIS

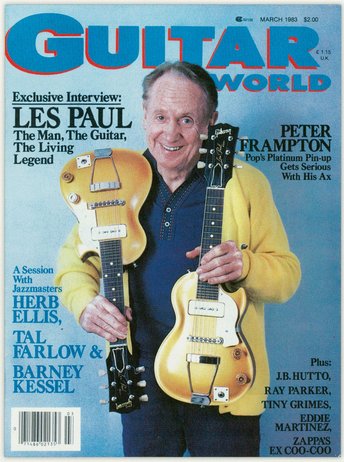

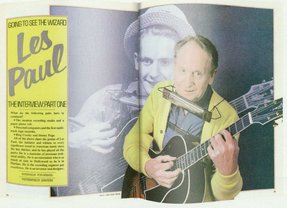

MARCH Legendary guitar inventor/ tinkerer Les Paul never stopped innovating—even when a 1948 car crash almost cost him an arm. “I figured, if they’re going to amputate my arm, I’ll play the guitar with one hand. To do that, I conceived the synthesized guitar, which you play with your left hand.”

COVER STORY BY PETER MENGAZIOL; PHOTO BY JOHN PEDEN

MAY Jaco Pastorius, one of the all-time great bass players, frowns on being called an original.

COVER STORY BY PETER MENGAZIOL PHOTO BY JONATHAN POSTAL

JULY Dixie Dregs leader Steve Morse talks about his gear, his guitar-playing philosophies, his influences...and his Georgia farm.

COVER STORY BY BILL MILKOWSKI PHOTO BY JONATHAN POSTAL

SEPTEMBER Toto guitarist and hired gun Steve Lukather offers advice on getting out of a session before it’s too late.

COVER STORY BY TIM BRADLEY PHOTO BY JOHN LIVZEY

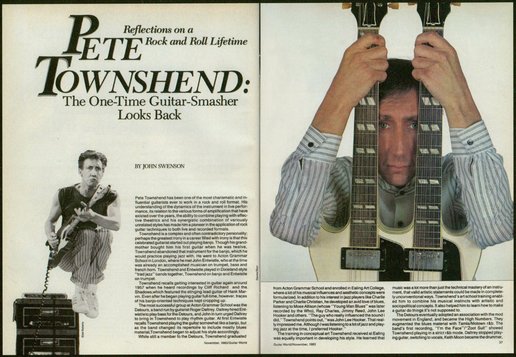

NOVEMBER The Who’s Pete Townshend comes clean about where the “windmill” came from. “The first time I swung my arm was after seeing Keith Richards do it the night before. But he must have just done it that one time and never did it again, so it developed into my trademark.”

COVER STORY BY JOHN SWENSON; DAVIES/STARR

JAN. 1983

VOL. 4 / NO. 1

Robby Krieger

The Doors guitarist recalls the formation of the legendary California rock band as well as the origin—and subsequent chart-topping success—of “Light My Fire.”

After high school came a year at the University of California at Santa Barbara, where Krieger majored in “keeping out of the Army,” he told writer Tim Bradley. “By that time, I had gotten more into flamenco and was actually giving lessons at the school.”

Krieger made the switch to electric guitar after seeing Chuck Berry perform at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium. He transferred to UCLA after the year at UC Santa Barbara and decided to major in physics. He had also come to a musical fork in the road. On the one side, he was playing in a band called the Psychedelic Rangers with drummer John Densmore, a buddy from University High School in Los Angeles. And on the other, he was also into Indian music. “They even had an Indian music class at UCLA at the time, which I took. I had a sitar and a sarod and took a lot of lessons on them. I even went to the Ravi Shankar school out here, which was called the Kinnara School. This was during Ravi’s heyday. He had about 10 teachers and millions of guys coming in with sitars.”

It was this interest in Eastern culture that indirectly led to the construction of the Doors. “John [Densmore] and I were doing his meditation class taught by a guy who had been a disciple of the Maharishi’s in India. Ray Manzarek, the Doors’ organist, happened to be in the class too. At that time, Ray was just forming a group with his brothers called Rick and the Ravens, and Jim Morrison was going to be the singer. They asked John to be the drummer and a couple of weeks later, they decided they needed another guitar player. John brought Jim over to my house and we hit it off good. So we rehearsed and that was it. At first, I never really thought anything would come of it, but after a couple of rehearsals and a couple of gigs, I thought we were incredible! I thought we were as good as anybody out there and I had no doubt that we would make it.”

Because of the overpowering presence of Jim Morrison and Krieger’s own mild-mannered and soft-spoken nature, it is not widely realized that many of the band’s greatest hits were from the Krieger quill: tunes like “Love Me Two Times,” “Touch Me” and one of the all-time greatest songs, “Light My Fire.”

“I never even thought about writing until one day Ray said, ‘Hey, you guys, we need some songs! Everybody go home and write some songs!’ So I went home and wrote ‘Light My Fire’ and ‘Love Me Two Times.’ Those are the first two songs I ever wrote, and it’s been downhill ever since. [laughs] They took about an hour or so. What I had for ‘Light My Fire’ was just the basic song and Ray added the [hums the famous organ signature intro] and we all arranged it together. That’s why it said ‘written by the Doors’ on the albums, because we all sort of worked on the songs together. As soon as we worked up ‘Light My Fire’ and played it at a few gigs, I knew it was a smash.”

With “Light My Fire,” the Doors went from being just a club band to being headliners. “It happened so fast that we were booked into a club date at Steve Paul’s The Scene in New York for six weeks. We were still in there when the song hit Number One on the charts. We could have been playing giant places and here we were stuck at The Scene making 20 bucks a night. One of the highlights of the whole Doors thing for me was when I was listening to the radio in 1967. They were doing the Top Five countdown and ‘Light My Fire’ had pushed out the song ‘Cherish’ [by the Association] for Number One. It was a thrill for Elektra Records, too; they’d never had a Number One song. They were going nuts. It climbed very slowly because they didn’t have enough records to ship out.”

Zappa Plays Van Halen

Dweezil Zappa was just 13 years old when this photo was taken; in it, he’s clutching a Kramer Voyager guitar that was given to him by Eddie Van Halen. It all started when Eddie attended a performance of Dweezil’s band at a high school arts festival. Dweezil’s ax kept going out of tune, so Eddie offered him this guitar featuring the patented Eddie Van Halen vibrato bar. “I’ve radically altered the finish since this photo was taken,” says Zappa. “I did some painting on it.”

MARCH VOL. 4 / NO. 3

LES PAUL

A Guitar World field trip to the master guitar innovator’s New Jersey home offers a glimpse into the history of recorded music.

AFTER A FEW EXITS ON Route 17 from New York to northern New Jersey we found Les’ secluded estate. Even if you didn’t know the exact address there were clues all around that told you which house it was—mainly the stacks of old speakers, the empty cartons with “GIBSON” on them, the old turntable lying in the sun and the unused studio baffle, all out in his back yard.

Les’ house is a living archive. In one room is the record cutting lathe that Les fashioned out of an automobile flywheel. That’s where he began his experiments with overdubbing via acetates. In another room is a test rig that he still uses to develop guitar pickups. Upstairs lie rows of guitars in cases; some are prototypes, some stock models and some are legends. The living room now houses the first eight-track recording studio ever built, a separate entity from the main recording studio in another part of the building. The house is in controlled disarray; new equipment is being installed and the older, vintage gear Les swears by is being refurbished and incorporated into this new studio. It’s a tinkerer’s paradise but a suburban housewife’s nightmare.

Les’ two great loves, music and invention, began when he was nine. “I started out two things in parallel at the same time: electronics and playing the piano, the drums, the saxophone, the harmonica—that was first—and the banjo and the guitar. This came at the same time I built my first crystal set, and from that my first amplifier.” So began Les Paul’s interest in music and the means for its reproduction.

Before dabbling in “recording,” Les tried to produce “multiples,” in his own terminology—in a very “acoustic” manner, using the only playback method at his disposal. “By 1928 I was punching holes in my mother’s piano roll, making multiples,” said Les. “Multiple recordings, sure! Punch a hole in the piano roll and the key goes down. When it was a wrong note, I found the right note. Then I found out that with some tape I could plug the hole back up again, punch it somewhere else. I was making my first multiples way back! The first that I’ve got on disk were about 1933.”

SEPTEMBER / VOL. 4 / NO. 9

The Def Leppard axman sings the praises of his new partner, Phil Collen.

WHEN GUITAR WORLD caught up with Def Leppard’s Steve Clark for the first time, Phil Collen had replaced Pete Willis on guitar and the band’s third album, Pyromania, was a chart-topping success fueled by its three Top 40 singles, “Photograph,” “Rock of Ages” and “Foolin’.”

“The band was starting to get a bit lazy,” Clark told writer Joe Lalaina, “but now that Phil has joined, his enthusiasm has rubbed off on everybody and has given the band a new lease on life. Our guitar playing is also more adventurous than it was when Pete was sharing guitar duties with me. Pete and I were usually chuggin’ along playing the same riffs. Phil has a different approach—we tend to play across each other.

“The style we adopted on Pyromania is not to play the same parts during a song. If you take one guitar away our music just wouldn’t sound proper. When we play different riffs that blend together it improves the sound incredibly.”

Also evident on Pyromania is the newfound approach to guitar harmonies adopted by Clark and Collen. “Guitar harmonies are a bit dated now, which is why we didn’t want to do them on Pyromania,” says Clark. “We did them on the last album, but we didn’t want to get in a rut of being a guitar harmony band. So on the current album we do them on the chords instead—I think that’s taking the harmony thing a step further.”

When asked about his influences, Clark had one very specific answer. “When I heard Jimmy Page, I said, ‘Dad, I want a guitar.’ What I liked so much about him was that he played amazing riffs with so much style and feel. From the moment I heard Page, I knew his type of music was what I wanted to play.”

As for what the future holds for Def Leppard, Clark commented, “Maybe we’ll add a keyboard player for our next tour. But no matter what happens, we’re not going to let the success of Pyromania get to our heads—no way.”

Muddy Waters Dies; Blues Legends Pay Respect

Delta blues legend Muddy Waters died on April 30, 1983, and Guitar World writer Rafael Alvarez was among those at the funera chapel on Chicago’s South Side where the great bluesman lay in rest during the first week of May. Among the many musicians who attended was George Thorogood, who commented. “It’s a great loss, of course.” In the parking lot behind the chapel, a visibly shaken Johnny Winter—“too depressed to talk,” according to his manager—sat in the back of a black limousine before being ushered into the chapel for the start of the 7 P.M. service on May 4. At the Restvale Cemetery burial service the following morning, B.B. King offered these words: “It’s like losing your father. It’s going to be years and years before most people realize how great he was to American music.”

NOV. 1983

VOL. 4 / NO. 11

Pete Townshend

Guitar World’s first cover story with the Who legend sees him reflecting on his many trademarks: feedback, windmilling and smashing guitars.

The Detours—the school band led by Roger Daltrey and featuring John Entwistle on bass and Pete Townshend on guitar—eventually adopted an association with the mod movement in England, and became the High Numbers. Soon after, Daltry stopped playing guitar and switched to vocals, Keith Moon became the drummer and the name changed again to the Who. The group steadily improved, developing a style centered around the astonishing instrumental technique of Townshend, Entwistle and Moon. Townshend experimented with rhythm guitar patterns, using feedback and distortion ingeniously.

“As the level went up,” said Townshend, “as people started to use bigger amps and we were all still using semi-acoustic instruments, feedback started to happen quite naturally.” He played a Rickenbacker guitar because the Beatles used it and “I liked the look of it.” His strange, almost non-musical approach to sound sculpture became tremendously influential.

Though his use of feedback was a trademark he developed on his own, much of Townshend’s visual style was patched together from a number of influences. He was a shrewd observer of the pop world and when he saw something that looked good he would often adapt it to his own style. Even his windmill chord-playing style, where he would swing his arm in an exaggerated circle above his head, and which earned him the nickname “Birdman,” was picked up from something he noticed Rolling Stones guitarist Keith Richards doing one night.

“The first time I swung my arm,” said Townshend, “was after seeing Keith the night before swinging his arm like a windmill. I thought I was copying him, so when we did a gig with them later I didn’t do it all night, and I watched him and he didn’t do it all night either. ‘Swing me what?’ he said. He must have just gotten into it as a warming-up thing that night, but he didn’t remember and it developed into my sort of trademark.

“There’s a lot we’ve pinched from the Stones—abso—lutely nothing from the Beatles, funnily enough—but the Stones were a local band for us. I saw some of their first gigs at Richmond, and all the girls I was going out with at the time were in love with one or the other of them. I was just a Rolling Stones substitute.”

Then one night something happened which was to change the course of history for both Townshend and the Who. The band was playing at the Railway Tavern, which had a low ceiling, and during one of his follow-throughs Townshend accidentally struck the neck of his guitar against the ceiling, cracking it. At first he was saddened by the loss of his costly instrument. Then he got mad. “I proceeded to make a big thing out of breaking the guitar,” he said. “I pounced all over the stage with it and I threw the bits on the stage and I picked up my spare guitar and carried on as if I had really meant to do it.”

Townshend’s guitar demolition quickly became the focal point of the group’s kinetic stage presentation. An early fan, Speedy Keen, who later went on to play in the Town-shed-produced group Thunderclap Newman, recalled the Who’s impact at that time. “The Who had become legendary. Townshend would go into the local music store and buy 10 Rickenbackers—in those days a Rickenbacker guitar meant real class; they cost about three hundred quid and anyone who owned one stood apart—and he would bust them all up in a week, then take ’em back without paying for ’em. This caused quite a stir at the time, for a guy to get three grand worth of guitars and bust them up.”

The basis of the live sound that would make the Who famous was established, but Townshend was still working out songwriting strategies, composing at home by multi-tracking on tape recorders. Townshend was less interested in becoming a great guitar player than in coming up with a great sound for the Who. His attitude toward the guitar was more of a composer’s than a soloist’s. “At the beginning, it was really more of a situation where I felt that the only way I was ever, ever going to make myself felt was through writing. So I really got obsessed with writing rock songs, and I probably concentrated far more on that than on any other single thing in my life.”