“STILL A WILD BEAST AT HEART”

In March 1912, at the beginning of his career as a popular author, Edgar Rice Burroughs wrote to a magazine editor with his latest idea for a yarn:

The story I am on now is of the scion of a noble English house—of the present time—who was born in tropical Africa where his parents died when he was about a year old. The infant was found and adopted by a huge she-ape, and was brought up among a band of fierce anthropoids.

The mental development of this ape-man in spite of every handicap of how he learned to read English without knowledge of the spoken language, of the way in which his inherent reasoning faculties lifted him high above his savage jungle friends and enemies, of his meeting with a white girl, how he came at last to civilization and to his own[,] makes most fascinating writing and I think will prove interesting reading, as I am especially adapted to the building of the “damphool” species of narrative.1

It was, the editor replied, a “crackerjack” idea. “You certainly have the most remarkable imagination.”2

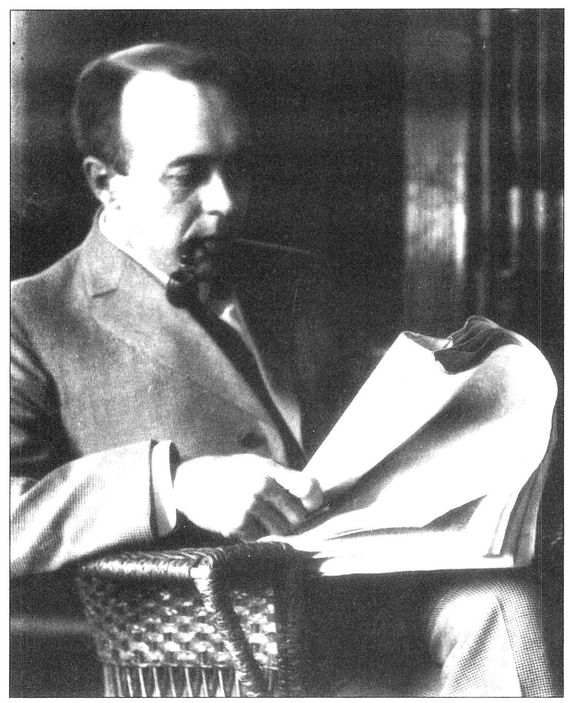

Edgar Rice Burroughs, 1912, © 1975 EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS. INC.

When Burroughs wrote Tarzan of the Apes he was thirty-six years old, married with two young children, and living in Chicago, the city of his birth. He was a sturdy though not especially imposing man, roughly five feet nine inches tall, with strong arms and hands.3 Far from living a life of rugged individualism, he worked in a minor position, giving professional advice to clients for System, “The Magazine

of Business.” “I knew little or nothing about business,” Burroughs later recalled, “had failed in every enterprise I had ever attempted and could not have given valuable advice to a peanut vendor.” To mesmerize clients, he took refuge in vague, portentous pronouncements and impressive if irrelevant charts and graphs. “Ethically,” he admitted, “it was about two steps below the patent medicine business,” in which he had also worked until the passage of the Pure Food and Drug Law in 1906 shut the enterprise down. To make matters worse, his boss was, in Burroughs’s words, “an overbearing, egotistical ass with the business morality of a peep show proprietor.”4

Burroughs thus wrote Tarzan as an act of self-liberation. He hoped to cast off the humiliations of a frustrated, insignificant white-collar worker for the independence of a commercial author with a mass readership. But more than merely a means of making money, the story, he hoped, would serve as an imaginative escape for himself and his readers. After he had become one of the most widely read (if never the highest paid) writers of his day, he made this point explicit. Speaking of the appeal of the Tarzan stories, he declared:

We wish to escape not alone the narrow confines of city streets for the freedom of the wilderness, but the restrictions of man made laws, and the inhibitions that society has placed upon us. We like to picture ourselves as roaming free, the lords of ourselves and of our world; in other words, we would each like to be Tarzan. At least I would; I admit it.5

In his own way, then, Burroughs was as much an escape artist as Houdini. The Tarzan escape emphasized not only freedom but also wildness, not only challenge but also combat, and it proved one of the twentieth century’s most popular and durable, performed by Burroughs himself in twenty-three additional Tarzan books, which were translated into a host of languages, as well as in magazine articles and newspaper serials, and by others in films, radio and television programs, cartoons, games, and toys.

As Tarzan carried escape art into the realm of fictional adventure, his body recalled Sandow’s. Tarzan represented Burroughs’s conception of the perfect man, a spectacular nude figure of strength, beauty, virility, violence, and command who extended many of the

themes popularized by Sandow. Like Sandow’s feats and Houdini’s escapes, Burroughs’s creation must be understood in historical context. Ubiquitous as the name Tarzan has become, the circumstances of his creation have been largely forgotten. If, however, we see both Burroughs’s situation and his protagonist’s in historical context, then we also see more clearly the pressures on manhood in the modern world and the urge to recover a primitive freedom and wildness.

Edgar Rice Burroughs never invited the confusion between creator and character that, as vaudeville headliners, Sandow and Houdini did. Instead, he was always acutely conscious of the gulf between his life as an author and the adventures of his alter ego, Tarzan. He was still more aware that until he was nearly thirty-six (an age at which the major portion of Sandow’s and Houdini’s careers was over) he was not a writer at all and might easily have never written a word of the Tarzan books or the other sixty-eight books, numerous short stories, and articles that he composed before his death in 1950. Had he died in the summer of 1911, just as he attempted his first professional fiction and five months before he started Tarzan of the Apes, he would have been virtually unknown. Even within his extended family, he may well have been regarded as a disappointment. Certainly he was a failure in his own eyes.

“Nothing interesting ever happened to me in my life,” Burroughs wrote in 1929, in the midst of his success. “I never went to a fire but that it was out before I arrived. None of my adventures ever happened. They should have because I went places and did things that invited disaster; yet the results were always blah.”6 This sense of belatedness, which his rueful humor could not disguise, dogged Burroughs from his childhood. Like many men who came of age in the 1880s and 1890s, he seemed born too late. The great adventures of his father’s generation, even of his elder brothers’, were over before he came on the scene. If young Ehrich Weiss had to struggle against the undertow of his father’s decline, young Ed Burroughs felt the pressure to match his father’s success. The very first sentence of the

unfinished autobiography in which he bemoaned his unexciting life declared, “My father, Major George T. Burroughs, was a cavalry officer during the Civil War.”7 George Burroughs’s early adult life certainly did not lack excitement. As part of the Union troops at Bull Run, he had felt a bullet pierce his blouse but, fortunately, not his skin. Four years later, with his new wife, Mary, he watched the bombardment of Richmond in April 1865, and left the service as a brevet major. Three years later he moved his family to Chicago, unquestionably the greatest American city for adventure in the late nineteenth century. In 1871, from the roof of their West Side townhouse near fashionable Union Park, he saw the most calamitous fire in American history tear through the heart of the city. Seizing on Chicago’s position as the capital of the nation’s grain market, George Burroughs entered the distillery business and quickly grew wealthy. After a fire in 1885 devastated his distillery, he shifted his enterprise to the American Battery Company, which made storage batteries, and ultimately assumed the position of president.

Burroughs when a boy of about ten. © 1975 EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS, INC.

Ed Burroughs was born on September 1, 1875 (one year after Houdini, eight years after Sandow), into a decidedly masculine household.

Three elder brothers—ages nine, eight, and three—loomed over him. Two other brothers who died in infancy cast shadows as well: Arthur, born in 1874, who survived only twelve days; and Charles, almost six years younger than Ed, who lived five months. “The earliest event in my life that I can recall clearly,” Burroughs later said, “is the sudden death of an infant brother in my mother’s arms.”8 As the youngest surviving child, Ed aroused considerable anxiety with his boyhood illnesses, which tightened his close bonds to his mother. He made up his first stories and told them to her during the times when he was confined to bed. Burroughs’s father valued a strict Victorian order in his household: meals were punctually served to the sound of a gong; all lights were extinguished when he went to bed. So too did he favor a conservative order in society at large. A staunch Republican, as his son would become in his turn, he attended the trial of the Haymarket bombers in 1887 and received a special permit to witness their execution as the city trembled in fear of violent insurrection—another great if grim adventure.9

Ed grew up a straggler, always far to the rear of his father’s expectations and his brothers’ example. In stature and in substance, he never seemed to measure up. His father stood six feet high, and his brothers were tall as well. The two eldest, George and Harry, graduated from Yale in 1889 and dutifully joined their father at American Battery. Almost immediately, however, Harry developed a serious cough from battery fumes, and a physician recommended a change of climate. The tonic of ranch life in the West was the great restorative for many men at this time, including Theodore Roosevelt, the novelist Owen Wister, and the painter Frederic Remington. The two brothers teamed up with a Yale classmate, Lew Sweetser, whose father and uncle ranked among the leading cattle barons in Idaho; backed by their respective fathers, the young men bought land for a cattle ranch in the southeastern portion of the newly admitted state. In the spring of 1892, sixteen-year-old Ed joined his brothers in what was certainly the most exhilarating six months of his youth. Sent west to escape an influenza epidemic, he seemed to step into the pages of a dime novel. Although the romantic days of the great cattle drives had waned, he could at least bask in their afterglow. He joined in roundups, learned to ride all day and all night, and returned brimming with stories of ornery horses (including one that “Sandow himself

could not have held … when he took it into his head to bolt“) and”likable murderers.”10

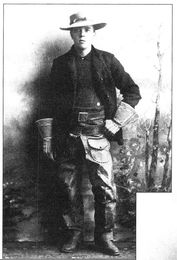

Burroughs in Western garb, Idaho. © 1975 EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS, INC.

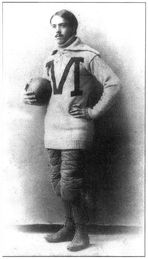

Burroughs in a football uniform, sporting a mustache, at Michigan Military Academy, 1895. © 1975 EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS, INC.

He at least glimpsed possibilities of self-transformation as well. A photograph from the time shows him looking at the photographer with the cockiness of a young cowboy, bulked up by his western garb, hand on hip, broad-brimmed hat shading his eyes as if the photographer’s studio were a dusty street in Dodge City.

Ed’s father wanted less rambunctious models for his youngest son, however. He shipped Ed off to Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, where another older brother, Coleman, was already enrolled. Ed flunked out after a single semester. His father then sent him to Michigan Military Academy, where Ed chafed under the tight discipline. As a plebe, he excelled chiefly in devising pranks and accumulating punishments. He rode in cavalry drill and played football, exaggerating his height by an inch and a half in a team description. He studied not only military tactics and mathematics but languages and literature as well. A drawing he made of Joan of Arc on the flyleaf of his French text gives us a glimpse of his inner imaginings. No slight maid, she is a formidable woman warrior with massive iron breastplates, an hourglass waist, ample thighs, and a conspicuously phallic sword dripping with blood.

Burroughs’s drawing of Joan of Arc, 1895. © 2001 EDGAR RICE BURROUGHS, INC.

Once Burroughs was graduated from Michigan Military Academy in 1895, it was time to gallop on a career, and though he had become an excellent rider, in this effort he found himself bucked and thrown again and again. The military offered the most obvious course, one that might please his father as well as fulfill his own youthful dreams. So when Burroughs failed the examination for West Point (as did the great majority of applicants), the wound to his pride cut deep. He returned briefly to Michigan Military Academy as assistant commandant. Then with impulsive bravado he enlisted in the army, requesting a cavalry assignment in “the worst post in the United States.”11 He got his wish and quickly regretted it. Burroughs may have thought he could recapture his father’s Civil War experience and also the Western cavalry’s glory days (gained at horrific cost to Plains Indians) as he rose in the ranks. But despite occasional chases of renegade Apaches, garrison duty at the Seventh U.S. Cavalry at Fort Grant in the Arizona Territory resembled convict labor far more than it did Buffalo Bill’s Wild West. After a bout of dysentery, Burroughs called on his father to pull the necessary strings to gain an early discharge. His military career had lasted ten months.

From 1897 until the appearance of Tarzan of the Apes in The All-Story magazine fifteen years later, Burroughs seemed inexorably pulled back to Chicago and to the world of business, try as he might to escape it. He took up his harness at American Battery under his father. A year later, when the Spanish-American War broke out in Cuba, he sought a commission. At one point he wrote directly to Theodore Roosevelt to join his Rough Riders, but he was turned down. (His dreams of military glory died hard: as late as 1906 he was inquiring about a position in the Chinese army.) Seeking then the escape route of his elder brothers and to recover the intoxicating summer of his adolescence, he returned on several occasions to Idaho—only to discover that his brothers’ cattle and gold-dredging operations represented not frontier adventure but a financial noose tightening around their necks. He briefly ran a stationery shop in Pocatello, Idaho, then gladly sold it back to its previous owner, concluding, “God never intended me for a retail merchant.”12 His marriage in 1900 to Emma

Hulbert, daughter of a prominent Chicago hotel manager, only increased the pressures of career. He made a final attempt to fit into his father’s designs at American Battery, where he served as treasurer, then fled west once again, with his wife, in an abortive effort to start a new life with his brothers or on his own. Even two decades later, he wrote, “It gives me a distinct sensation of nausea, accompanied by acute depression every time I think of my experience at the plant.” He added sarcastically, “I have about the same pleasant recollections of each and every business connection I had in the past.”13

Back in Chicago after 1904, Burroughs struggled like a character in an O. Henry short story or, more desperately, a Dreiser novel to stay afloat amid the hordes of scrambling white-collar workers who by the end of the decade represented one-fifth of the entire male labor force.14 He started as timekeeper on a construction site, then took “a series of horrible jobs” as salesman. “I sold electric light bulbs to janitors, candy to drug stores and [multivolume sets of the author John L.] Stoddard’s Lectures from door to door … . My main object in life was to get my foot in somebody’s door and then recite my sales talk like a sick parrot.”15 He put in longer stints as an office manager for one firm and then “as a very minor cog in the machinery” of Sears, Roebuck’s enormous mail-order business, supervising a large group of (mostly female) stenographers as they cranked out thousands of letters a day.16 None of these positions suited his restless, independent nature. Attempts to start a small business and thrive as his father had done—in advertising, patent medicine, a correspondence course in “scientific salesmanship”—all failed miserably. The birth of his first two children in 1908 and 1909 quickened his downward plunge. He felt near bottom, financially and emotionally. “I had worked steadily for six years without a vacation,” he later wrote, “and for fully half of my working hours … I had suffered tortures from headaches. Economize as we would, the expenses of our little family were far beyond our income. Three cents worth of ginger snaps constituted my daily lunches for months.” He pawned his wife’s jewelry and his watch to buy food. He “loathed poverty” and loathed himself for being in it. With the damning judgment of a conservative businessman, he wrote: “It is an indication of inefficiency, and nothing more.”17

Burroughs’s frustrations were shared by countless millions; indeed, they would become a prominent theme in twentieth-century American

literature: from Theodore Dreiser’s Sister Carrie to Saul Bellow’s Seize the Day. Willy Loman’s son Biff voiced them at mid-century in Arthur Miller’s play Death of a Salesman when he exclaims: “It’s a measly manner of existence. To get on that subway on the hot mornings in summer. To devote your whole life to keeping stock, or making phone calls, or selling or buying. To suffer fifty weeks of the year for the sake of a two-week vacation, when all you really desire is to be outdoors, with your shirt off. And always to have to get ahead of the next fella.”18

Burroughs tried other, almost parodically marginal businesses with no better success: a sales agency for lead-pencil sharpeners; then, under his brother Coleman, a manufacturer of scratch pads. In the office doldrums, he tried another moneymaking scheme that might have seemed still more chimerical: writing commercial fiction for the “pulps.”

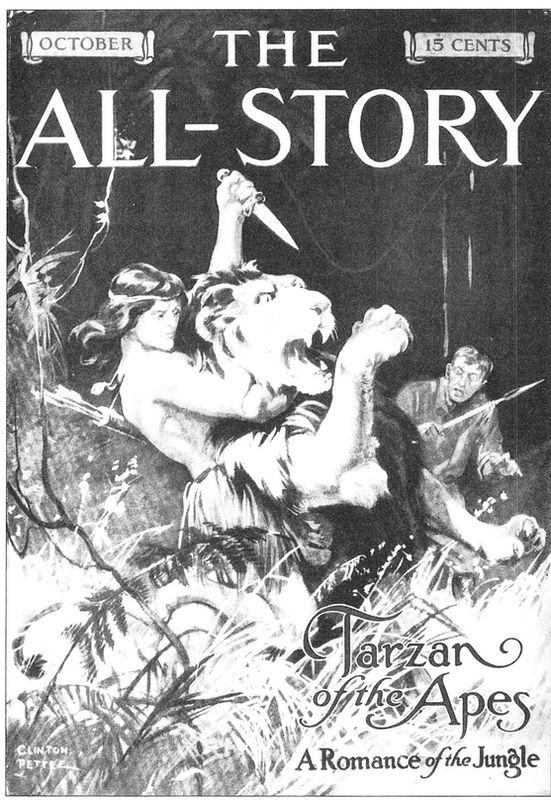

Pulp magazines were so called because of the inexpensive, porous paper on which they were printed. They specialized in stories that were formulaic concoctions, long on twisting plot, offered in doublecolumned monthly installments to a mass readership. Tales of adventure, mystery, war, the Wild West, and science fiction were their stock-in-trade. These attracted a predominantly male following of adolescent boys and both blue- and white-collar men, as well as a significant number of women, as readers’ letters attest. They were read at home, especially on Sundays, while traveling to and from work, and in idle moments on the job. In some respects, writers for the pulps might be compared to performers in the small-time vaudeville in which Harry Houdini began his career. Both worked hard for low wages and tried to entertain a diverse, unpretentious public. If vaudeville was industrialized in its specialized acts, systematized format, and centralized management, pulp magazines were fiction factories dominated by big publishers that demanded from authors a combination of literary facility, stamina, and speed. Pulp writers received as little as a tenth of a cent per word. And just as small-time vaudevillians dreamed of hitting the big-time houses, many pulp writers aspired to break into the “slicks,” the more prestigious mass-circulation magazines printed on smooth stock, such as Collier’s and The Saturday Evening Post, that paid thousands of dollars for a single story. Vaudeville achieved its height between the 1890s and the Great War. But as

successors to the cheap story papers of the nineteenth century, pulp magazines early in the second decade of the twentieth century were just entering their golden age, which continued through the 1930s.19

Burroughs himself derided pulp fiction and claimed to have stooped to it only because he needed the money. Keenly aware of the divide between “good” literature addressing a “gentle reader” and sensational fiction with no cultural pretensions, he knew that the pulps were not aesthetically respectable. In fact, he said he became acquainted with their contents by happenstance, though his quick mastery of their formulas suggests a longer and deeper acquaintance. Because one of his shaky business ventures took advertising in their pages, the office received copies of magazines to check the ads. Burroughs brought some of them home to read. “It was at that time,” he later recalled, “that I made up my mind that if people were paid for writing rot such as I read in some of those magazines that I could write stories just as rotten.”20

His first novel, A Princess of Mars, begun in July 1911 on leftover stationery from his failed enterprises, portrays the adventures of John Carter, a Virginia gentleman, Civil War veteran, and Indian fighter who falls into a trance in Arizona and wakes up on Mars. Carter was a kind of dream self into whom Burroughs poured many of the masculine endowments and accomplishments he most admired:

a splendid specimen of manhood, standing a good two inches over six feet, broad of shoulder and narrow of hip, with the carriage of the trained fighting man. His features were regular and clear cut, his hair black and closely cropped, while his eyes were a steel gray, reflecting a strong and loyal character, filled with fire and initiative. His manners were perfect, and his courtliness was that of a typical southern gentleman of the highest type.

His Mars is inhabited by two races: a reddish one, who resemble earthly humans; and a hideous green one, whose warriors are fifteen feet tall, with an extra set of limbs and curved tusks. Except for ornaments, all go naked, as does Carter himself. He soon falls in love with a beautiful copper-skinned princess, and the first-person account describes his swashbuckling adventures on behalf of her and her people

as he seeks to save her from the cruel, lustful monster who commands the green race. Finally, after slaying multitudes and proving himself the finest warrior on the planet, he has the satisfactions of restoring order, being proclaimed a hero, and marrying the princess. “Was there ever such a man!” she marvels. “Alone, a stranger, hunted, threatened, persecuted, you have done in a few short months what in all the past ages [on Mars] … no man has ever done.” Though the tale ends on a note of longing, its great theme is manly triumph both in combat and in romance.21

So self-conscious was Burroughs about setting down such an extravagant fantasy and about being a writer at all that he wrote surreptitiously and under the pen name Normal Bean (that is, normal brain). He sent the first forty-three thousand words of the story to the editors of The Argosy, one of several magazines in the publishing stable of Frank Munsey, the man who started the modern pulp-magazine revolution. Ten days later, he received a highly encouraging letter from Thomas Mletcalf, an editor of The All-Story, a sister publication. Spurred by Metcalf, Burroughs finished the story the following month and sold it for four hundred dollars. This amounted to barely more than half a cent a word, but in his autobiographical sketch Burroughs still savored the thrill of this, “the first big event in my life.”22

Clearly, such writing tapped both a talent and a need in Burroughs. Aside from a crude “historical fairy-tale” called “Minidoka” that he had concocted for his nephew and niece in Idaho a decade earlier, he appears not to have written fiction before and certainly none of any length. Now it seemed he could not stop. Already, while Metcalf deliberated over the Martian romance, Burroughs wrote a second novel-length story, a medieval swashbuckler called “The Outlaw of Torn.” Then, with an office manager’s precision, he noted that on December 1, 1911, at eight in the evening he began to write the novel that would become Tarzan of the Apes.

To appreciate fully the meaning of Burroughs’s dreams of manly triumph in Africa, we should first look more closely at the magazine he so eagerly left to plunge into pulp fiction. After the scratch-pad business,

like the lead-pencil sharpener agency, collapsed, Burroughs took what turned out to be his last job other than that as a self-employed writer. From shortly after he began writing stories in the summer of 1911 until early in 1913, when he felt his sales could support his growing family, he worked as manager of the business service department of System, a business magazine run by A. W. Shaw. Though Burroughs had almost nothing good to say about any business in which he worked, the experience at System aroused by far his sharpest invective. “I never so thoroughly disliked any employer as I did Shaw,” he remembered, as if rubbing a wound that refused to heal. Perhaps at the root of Burroughs’s disgust lay his sense of fraudulence and incompetence in dispensing business advice in response to individual requests, a service the magazine provided for an annual fee of fifty dollars. “I recall one milling company in Minneapolis or St. Paul who submitted a bunch of intricate business problems for me to solve. Had God asked me to tell Him how to run heaven, I would have known just as much about it.” His boss’s indifference to Burroughs’s lack of qualifications only confirmed the fraud. Burroughs scornfully remembered, “Shaw also had a young man about nineteen giving advice to bankers. This lad’s banking experience consisted in his having beaten his way around the world.”23

In three crucial respects, System was the mirror image of the masculine world of pulp magazines in which Burroughs sought refuge and profit. First, to a startling degree, issues of manliness suffused its depiction of modern business. To read its pages is to discover an ethic of intense work and competition that both shaped and repelled Burroughs—to discover, that is, the “iron cage,” in the sociologist Max Weber’s phrase, from which he strove to escape.24 If magazines such as The All-Story divulged a world of primarily (though not exclusively) masculine fantasy, offering satisfactions denied on the job, System presented an alternative world in which masculine adventure lay at the core of business competition. Second, System proposed a hierarchy of masculine worth and ability that emerged from competition. Whether this hierarchy was due to differences in training and environment or innate differences (an issue that Burroughs explored in Tarzan of the Apes) was a question to which it offered an equivocal response. Third, System was also a magazine of stories. Though all the incidents described in its articles were allegedly true, much of the writing was either

about decisive actions that businessmen had taken or about tales of adventure in the context of modern business.

Many of the narrative devices in the System articles borrowed from fiction. A problem would be introduced by a remark or exchange in direct, “manly” speech, and the story then proceeded with rapid paced action to a clear outcome with a business moral. This was not a magazine concerned primarily with impersonal business processes and economic forces, though it did promise to extract underlying principles that readers could apply to their own situations. Rather, it concerned men who had the power to assess problems, chart their courses, and control events, coming out on top as one of the “big men.” One might well suspect that writers contrived details, concocted dialogue, occasionally invented an informant, or even made up much of the supposedly true accounts of business advice. But even if authentic to the last detail, its stories shared a clear house style designed to appeal to readers seeking entertainment as well as information.

The November 1911 issue of System is one which Burroughs would have seen and, quite possibly, read just as he prepared to put his first Tarzan story on paper. Consider the title. “System” was a word that glittered with magic in the early twentieth century. It carried the promise of a scientific modern order. New system builders were eager to apply methods of rationalization, coordination, centralization, and supervision to ever-larger organizations of people and machines, including vast new office bureaucracies, immense factories, and far-flung financial empires. By this time, the great investment banker J. Pierpont Morgan, Jr., had consolidated and expanded corporations such as United States Steel (1901), International Harvester (1902), and American Telephone and Telegraph (1906). In 1911 Frederick Winslow Taylor, articulating his vision of maximum industrial efficiency, declared, “In the past, the man has been first; in the future the system must be first.” In Highland Park, Michigan, Henry Ford was developing his revolutionary system of production for the Model T car. The skyscraper was the cathedral of this emerging corporate order, the modern electrified factory its palace. And regimented, synchronized movement increasingly constituted its dance. At the very same time that Ford was developing his assembly-line system, Broadway choreographers were creating its inverted image in

the modern chorus line. “It is system, system, system, with me,” declared a leading choreographer, Ned Wayburn, in 1913. “I believe in numbers and straight lines.”25

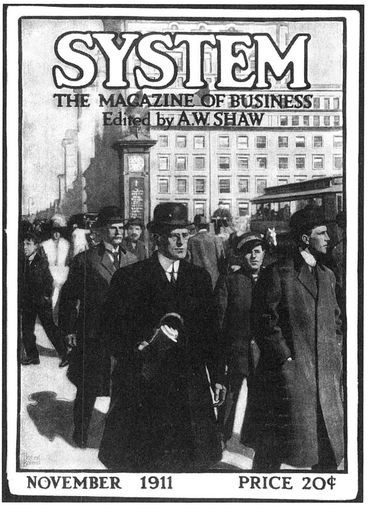

How was one to operate within this modern, urban world of business and stand out? The answer of System’s November 1911 issue began on its cover, which shows a crowd, principally of men, walking in a business district. The man in the forefront, more fully drawn than the others, models the characteristics of the exemplary businessman thriving in the urban corporate world. Well dressed but not ostentatious, bowler snug as a helmet, newspaper furled, and walking stick at the ready, he does not need to look at the clock behind him to know that time is money. Unlike the messenger just to the right, or the stoop-shouldered man at the very center retreating down the street, or the boy with hand in pocket walking into the left margin of the picture, he strides full of purpose on his mission.

The opening article offered inspiring accounts of individual business success as part of a series, “Ideas That Have Been Put to Work.” Breathlessly, the piece begins: “In a flying spark that bridged a broken wire, Edison saw not merely a manifestation of electricity, but the possibility of electric light. In the steam escaping from a kettle of water, Watt saw a power that he harnessed for the development of our industries. So many of the world’s greatest ideas have been suggested by trivial observations that have been adapted to the needs of the hour.”26 The article proposed to apply this heroic view of flashing genius to the world of modern business, with vignettes demonstrating breakthroughs using analogical thinking, even as it stressed the importance of interdependence, systematization, standardization, supervision, and expansion. For example, a manufacturer discovers how to make his sales force a more cooperative team by watching a football game. A store manager at the theater notes the use of a revolving stage and realizes he can apply it to his shopwindows, vastly expanding his possibilities of exhibiting goods with a four-part revolving display. A baker learns from the success of packaged laundry starch to emphasize the hygienic values of packaged bread. These are anecdotes about active, decisive, inventive men, often (though not exclusively) attuned to machinery and certainly to organization. They are adult Tom Swifts, eager to scale the business ladder.

“What Are Profits?” asks the next article, at first glance a dusty

disquisition by F. W. Taussig of Harvard’s economics department. Its real subject, however, is the meaning of manliness in a modern capitalist society. A leading economist, Taussig was the son of a successful physician and businessman who had immigrated to the United States from Prague. He quickly described the hierarchy of manly achievement in the business world and directly addressed the issue of why some men succeed and others fail:

Some men seem to have a golden touch. Everything to which they turn their hand yields miraculously. They are the captains of industry, the “big men,” admired, feared and followed by the business community. Others, of slightly lower degree, prosper generously, though not so miracutousty—the select class of “solid business men.” Thence, by imperceptible gradations, there is a descent in the industrial and social hierarchy until we reach the small tradesman who is, indeed, a business man, but whose income is modest and whose position is not very different from that of the mechanic or the clerk.

The cover of System, November 1911. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Taussig went on to consider whether such varieties in position stem from “differences in inborn abilities” or from “training and environment.” (If Burroughs were reading, his eyes must have widened with interest.) With some qualifications, Taussig answered that at the highest level they are indeed innate: “Captains of industry are doubtless born. So are great poets, musicians, men of science, lawyers. Though there may be occasional suppressed geniuses among the poorer classes, ability of the highest order usually works its way to the fore.” Not surprisingly, he believed that merit thrives in a laissez-faire economy. Still, for those not touched with genius, he acknowledged, other qualities were critical, including “the advantages of capital and connection,” “imagination and judgment,” administrative ability, “courage,” and a body “vigorous in its capacity to endure prolonged application and severe nervous strain.” Surveying the various types of men who succeeded in the business world, he concluded, “Among all these different sorts of persons, a process very like natural selection is at work.”27 Implicitly, this process affirmed the essential rightness of business and other social hierarchies, which he believed reflected fundamental and progressive hierarchies of nature.

After an item on making money from waste, “What’s Your Scrapheap Worth?” there was a piece by Henry Beach Needham, “How to Select the Right College Man.” One might fairly say that System was fascinated with processes of selection—whether of kinds of scrap or kinds of men—with distinguishing the exceptional individual from the mass. The college article noted that a higher proportion of college men were going into business and quoted business leaders who wanted college graduates for executive positions. (One imagines Burroughs squirming, since he was among the more than 95 percent of American men at this time who never attended college.28) The article at one point casually observed that the college man “has survived [in various capacities in Western Electric] because he is ‘the fittest.’” The Darwinian analogy was clearly becoming a commonplace. Enos Barton, chairman of the board of Western Electric and recently retired as its president, declared, “The college … is a sort of

sieve—a coarse sieve wherein the best men are sifted out … . By our method of selection the loafers and the sports are eliminated.”29

In the following piece, “Players in the Great Game,” the subject remains the “big men,” the “men who are factors in the march of progress.” The first figure discussed is Irving T. Bush, who by sticking to one thing (Burroughs squirms again) is worth twenty-six million dollars at the age of forty-three. “Physically, too, Mr. Bush is big—in all some six feet and two inches, with a heart of proportionate size.” He has just given a check for ten thousand dollars to his sales manager. Another “player” in the “Great Game” is Edward R. Stettinius, president of Diamond Match (and later a partner in J. P. Morgan and a key industrialist in the Allied effort during the Great War). He “sits behind his big desk in his big office … . As the conversation progresses, Mr. Stettinius directs it, using a half-burned cigar as a baton … . [H]is movements are quick and vigorous.”30 (Burroughs crunches a gingersnap.)

As a whole, the articles in System depicted a world of big, energetic, masterly leaders—and, implicitly, of smaller, unexceptional followers. It was a view cogently if smugly expressed by one of the largest manufacturers of the day, Cyrus McCormick, Jr., a man born with a silver reaper in his mouth. In answer to a query, “Upon what ideals, policies, programs, or specific purposes should Americans place most stress in the immediate future?” this commander of fifteen thousand workers replied: “Civilization needs leaders, but it is equally essential there should be followers. Nature has so provided that for one man capable of the larger task of brain or brawn, tens of thousands are unequal to it. In the frank recognition of this natural law, and the acceptance of it, and obedience to it, much depends.”31

A different but equally telling perspective emerges from the advertising section of System. The advertisements may also be read as narratives of manliness, which directly speak to readers concerned about their inadequacy. No talent is simply innate, they seemed to say; any man can benefit from training, advice, or nostrums. The System articles focused on the “big men,” but the advertisements promised to aid those who had fallen behind. Many offered correspondence courses and other instruction by mail. (Burroughs would hardly have glanced at these, given that one of his many failed ventures had been a correspondence course in “scientific salesmanship.”)

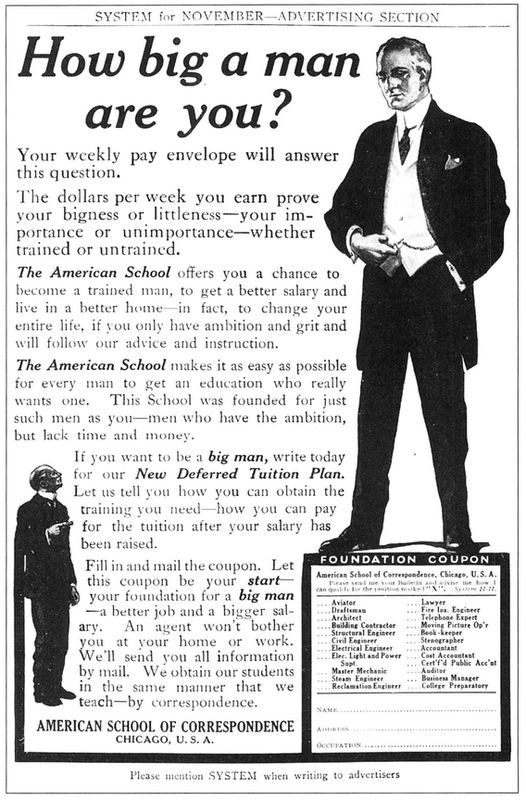

“How big a man are you?” an advertisement for a correspondence school in System, November 1911. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

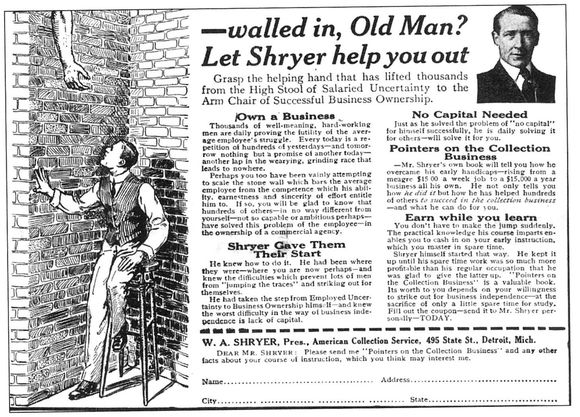

“Walled in, Old Man?” an advertisement in System, November 1911. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

“How big a man are you?” one ad demanded. A large, prosperous, and distinguished-looking man, with his suit coat open to reveal a vest and massive watch chain and with his hand cradling a watch, stands staring down on a smaller, thinner, halding, rumpled, and rather cringing figure. The copy declared: “Your weekly pay envelope will answer this question. The dollars per week you earn prove your bigness or littleness—your importance or unimportance—whether trained or untrained.” The American School of Correspondence promised to make the difference.

Helping hands stretch forth in other advertisements for similar services. “Walled In, Old Man?” inquires one in which a clerk sits on his stool, shut in a corner of high brick walls, while from the top of the picture a strong hand reaches down. “Grasp the helping hand that has lifted thousands from the High Stool of Salaried Uncertainty to the Arm Chair of Successful Business Ownership.” “Go,” exhorts another as a man in suit and tie helps a more modestly dressed man up a rocky, thorny slope, and, by implication, to an office desk and a solidly middle-class life.

“Go,” an advertisement for another correspondence school in System, November 1911. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Burroughs wanted to escape his job at System and the entire world it represented—in many respects, the world of his father’s values, honed to a sharp competitive edge—but he was profoundly shaped by it. And though he claimed to hate business, he approached his new career in commercial fiction like a character out of the pages of System. The magazine celebrated charts and graphs as indexes of scientific efficiency, and from the time he began writing, Burroughs kept a graph of his word output over his desk. (It quickly rose to a peak in 1913, the first year he wrote full-time, with 413,000 words.32) He proved a canny bargainer with magazine editors, publishers, and film companies; a shrewd marketer of syndication and subsidiary rights; and, beginning in 1923, the successful owner of his own corporation, Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.

The story that made this new career possible was Tarzan of the Apes. Writing it, Burroughs discovered his potential as a commercial author and the possibility of a new life (his unpublished autobiography

essentially ends with this new birth). More important, he discovered a rich cluster of themes with immense cultural as well as personal resonance. Their continuing fascination contributes much to Tarzan’s enduring fame.

On every side in the early twentieth century, age-old questions about the basis of individual merit and social hierarchy demanded new answers. Reformers and radicals of various stripes questioned the legitimacy of special privilege and entrenched power. Swept by a flood tide of immigrants, the nation swirled with an unprecedented diversity of ethnicities, religions, and cultures. Extremes of wealth and poverty, power and impotence challenged egalitarian beliefs. The sense that American society was a sharp pyramid, with figures scrambling to reach its summit or at least advance up its steep slopes—the idea projected in the pages of System—pervaded all classes. Those who felt themselves rightfully on top strenuously justified their positions by appeals to hierarchies, particularly those of race (whiteness), gender (masculinity), religion (Protestant Christianity), and putative superiority of body, mind, character, and merit, and they did their best to repel all radical and leveling forces. From their high fortresses, they rolled boulders down on new immigrants, African Americans, agrarian and industrial radicals, feminists, socialists, and anarchists.

Yet their assaults were not merely defensive. The contest between conservatives and reformers over the shape of the American social and economic order took place against a larger international backdrop in which new hierarchies were being violently asserted. Burroughs’s generation had grown up during the great wave of European imperial expansion, when a fifth of the world’s landmass (excluding Antarctica) and a tenth of its population had been seized by European powers, great and small. Britain, whose national symbol, appropriately, was the lion, claimed the largest share: one-quarter of the land and one-third of the people on the globe.33 With the United States’ own frontier exhausted, the excitement of a new global land rush with immense prizes to the victors was hard for many Americans to resist.

Particularly in the flush of the nation’s triumph in the Spanish-American War, expansionists jubilantly proposed to revitalize their numbers by carrying the battle to new realms of empire. The Indiana Republican Albert Beveridge perfectly captured this spirit in his jingoistic paean on the floor of the U.S. Senate in 1899: “God has not been preparing the English-speaking and Teutonic peoples for a thousand years for nothing but vain and idle self-contemplation and self-admiration. No! He has made us the master organizers of the world to establish system where chaos reigns … . He has made us adept in government that we may administer government among savage and senile peoples.” “We will renew our youth at the fountain of new and glorious deeds,” Beveridge declared. Here was “system” with a vengeance.34

This dream of white Anglo-American revitalization and conquest not only transformed American foreign relations; it also profoundly affected American thinking, as is evident in popular fiction. Conspicuous in many popular novels of the early twentieth century are concerns with what might be called geographies of rugged masculinity: regions within which white men of northern European stock reassert their dominance over physical and moral “inferiors,” including incompetents, malefactors, weaklings, and cowards.

One such realm was the West, in which Owen Wister placed his immensely popular and influential novel The Virginian (1902). A historical romance, the story celebrates the adventures of a homegrown noble savage, “a slim young giant, more beautiful than pictures,” who is twice compared to a Bengal tiger. Like so many Westerns (and, as we shall see, other works), it both glories in wildness as the basis of masculine freedom and insists on the necessity of imposing social order. In the heyday of the cowboy in the Wyoming territory, that order was established by the individual man. The code of this society is simple: whether in bets, card games, or horse trades, “a man must take care of himself.” If this code is violated, the gun and the rope are the modes of redress, lynch law and the duel the courts of justice. As the title character declares, “[E]quality is a great big bluff … . [A] man has got to prove himself my equal before I’ll believe him.” Being equal to the occasion is the only kind of equality that counts. Burroughs, who did not remark on many literary works, called The Virginian “one of the greatest American novels ever written.”35

If the Western was one popular genre of masculine adventure, what might be called the Southern became another. Here the most influential work was Thomas Dixon’s The Clansman (1905), a book immediately controversial and now infamous for its vehement espousal of white supremacy and glorification of the Ku Klux Klan. Adapted as a play, it helped to spark wholesale assaults on African Americans in the terrible race riot in Atlanta in 1906. D. W. Griffith created his brilliant, disturbing film version, The Birth of a Nation, in 1915.

The novel has a number of points in common with Wister’s The Virginian: it is also a historical romance with a slender, handsome, raven-haired white Southern hero who reaffirms his manliness in mortal combat in a plot in which lynch law figures conspicuously. Here, too, the story ends with marriages symbolizing the reunion of regions—New England and the West in The Virginian, the North and the South in The Clansman. Unlike The Virginian, however, The Clansman associates wildness and animality not with natural nobility but with African American savagery and immorality. The most flagrant instance occurs in Dixon’s description of the rape of a white Southern virgin by the evil mulatto Gus. The author could not decide which wild beast to invoke:

Gus stepped closer, with an ugly leer, his flat nose dilated, his sinister bead-eyes wide apart gleaming ape-like as he laughed.

…The girl uttered a cry, long, tremulous, heart-rending, piteous.

A single tiger-spring, and the black claws of the beast sank into the soft white throat and she was still.36

At the novel’s conclusion, of course, the men whom Dixon regarded as the South’s and the nation’s proper white leaders reassert their authority against such usurpers. Anything else, Dixon made clear, would pervert morality, politics, religion, history, and biology. In a fair fight, he believed, their triumph was inevitable: “The breed to which the Southern white man belongs has conquered every foot of soil on this earth their feet have pressed for a thousand years. A handful of them hold in subjection three hundred million in India. Place a dozen of them in the heart of Africa, and they will rule the continent unless you kill them.”37 In Dixon’s fervid imagination, the rise of the “invisible

empire” of the KKK was part of the march of visible white empires across the globe.

The far North was a third testing ground of masculinity in the novels and stories of Jack London. A year younger than Burroughs, London had virtually completed his extraordinary career as a writer of popular fiction before Burroughs even got started. He began publishing stories about Alaska in pulp magazines in his early twenties and wrote fifty-one books before his death at the age of forty in 1916. Burroughs both admired London’s fiction and was fascinated by his turbulent life.38 He would certainly have known The Call of the Wild (1903), London’s first great popular success.

Buck, the hero of The Call of the Wild, is a dog rather than a man, a shift in species that allowed London to explore themes of savagery, violence, and primitivism with special power and directness. Half Saint Bernard and half Scotch shepherd, Buck has previously lived as a “sated aristocrat” on a California ranch, “with nothing to do but loaf and be bored.” In the novel’s opening pages, however, he is stolen and sent north to satisfy the demand for sled dogs created by the Klondike gold rush of 1897: “He had been suddenly jerked from the heart of civilization and flung into the heart of things primordial.” The fierce demands of the life of a pack dog in the harsh Northland transform him physically, morally, and spiritually:

His muscles became hard as iron, and he grew callous to all ordinary pain … . He could eat anything, no matter how loathsome or indigestible; and … [build] it into the toughest and stoutest of tissues. Sight and scent became remarkably keen, while his hearing developed such acuteness that in his sleep he heard the faintest sound and knew whether it heralded peace or peril.

At the same time, Buck increasingly recovers the instincts of his wild ancestors and, in reveries, the memory of his primeval companion, early man: “The hairy man could spring up into the trees and travel ahead as fast as on the ground, swinging by the arms from limb to limb, sometimes a dozen feet apart, letting go and catching, never falling, never missing his grip. In fact, he seemed as much at home among the trees as on the ground.” Buck learns to compete in the

“ruthless struggle for existence,” “the law of club and fang.” “He must master or be mastered; while to show mercy was a weakness.”39 Just as the Virginian must ultimately duel the evil cowpuncher Trampas, Buck must engage in a fight to the death with the treacherous husky Spitz. Unalike the Virginian, however, he has no Vermont schoolmarm pleading with him not to fight, and he easily learns to glory in the joy of the kill.

In the course of the story, the Northland pitilessly exposes both animal and human incompetence and weakness. Buck achieves his position as lead dog through his willingness to fight rivals to the death and maintains it through his incomparable strength and sagacity. Dogs are no more created equal in London’s tale than men are in Wister’s.

Like Wister and Dixon, London gave readers a romance, in his case between Buck and his “ideal master,” John Thornton. Thornton, too, has joined the quest for gold, though apparently animated more by delight in the wilderness and joy in the quest than by the riches to be gained. As Buck increasingly responds to the ancestral “call of the wild,” only his love of Thornton holds him back. He hungers for tougher challenges, bigger game. He kills a bear, then a moose, and when he discovers Thornton slain by members of the Yeehat tribe, he kills man, “the noblest game of all.” At the novel’s conclusion, he has been transmuted to legend, the great Ghost Dog fabled by the Yeehats who runs at the head of a wolf pack, “leaping gigantic above his fellows, his great throat a-bellow as he sings a song of the younger world.”40

When Burroughs dropped his infant “scion of a noble English house” into tropical Africa, another harsh and savage realm that would test the character of modern masculinity, he was adapting a well-known theme. As he later recalled, “I was mainly interested in playing with the idea of a contest between heredity and environment. For this purpose I selected an infant child of a race strongly marked by hereditary characteristics of the finer and nobler sort and at an age at which he could not have been influenced by associations with creatures of his

own kind. I threw him into an environment as diametrically opposite that to which he had been born as I might well conceive.”41

To a conservative white American of Burroughs’s background and training, the jungle of Equatorial Africa brought together the starkest possible conjunction of “primitive” indigenous peoples, exotic wilderness, savage animals, and both noble and venal colonial explorers. Burroughs knew little about Africa at this point and later declared that he wrote Tarzan with the aid of only Henry Stanley’s In Darkest Africa (1890) and a fifty-cent Sears dictionary.42 Probably, his deepest direct contact with African culture had occurred on the Midway at the 1893 Chicago world’s fair as he drove by the Dahomey Village in a “horseless surrey” sponsored by his father’s American Battery Company. He would have grown up reading accounts of romantic European explorers, even though he was aware that in the years since his birth, Africa had quickly passed from being the object of the most lofty professions of philanthropy to being the target of the most rapacious imperial greed. More particularly, he would have read extensive newspaper accounts of one of the first modern mass atrocities, the enslavement and death of millions in the Congo Free State under the aegis of King Leopold II of Belgium. Still, Burroughs’s Tarzan remains much more in the tradition of R. M. Ballantyne’s 1862 novel for young readers, The Gorilla Hunters (“I say, boys, isn’t it jolly to be out here living like savages?”), than in that of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness (1902).43 Despite Conrad’s searing depiction of evil at the core of the “civilizing” enterprise, tropical Africa remained in Burroughs’s and the public’s imagination a great arena for white male adventure, one of the last wild places on earth.

To carry the “hereditary characteristics of the finer and nobler sort” into this demanding environment, Burroughs, who took great pride in his Anglo-Saxon ancestry, selected members of the British nobility, John and Alice Clayton, Lord and Lady Greystoke. The story opens in 1888 with John Clayton and his young, pregnant wife bound for West Africa, where he plans to investigate reports that Britain’s native subjects are being exploited and enslaved by another European power (sounding much like Belgium) in pursuit of ivory and rubber. Burroughs cast Clayton from the same mold as his previous hero, John Carter, in A Princess of Mars. Above average height, with a military bearing and regular features, he is “a strong, virile

man—mentally, morally, and physically.” By contrast, the crew of the small vessel on which John and Alice sail from Freetown on the West African coast toward their final destination typify the lowest elements of society, socially, morally, biologically. The officers are “coarse, illiterate,” “swarthy bullies” led by a “brute” of a captain, and the crew that mutiny against their thuggish command are even more villainous and animalistic.44 In their atavistic appearance and savage proclivities, they virtually step from the pages of Cesare Lombroso’s highly influential Criminal Man.45 In Burroughs’s description, their leader, Black Michael, “a huge beast of a man, with fierce black mustachios, and a great bull neck set between massive shoulders,” anticipates the apes that will play such a prominent part in the story. Burroughs poured ice water into Clayton’s veins, allowing him to stroll across the deck of the ship in the midst of the mutiny as casually as he might stroll across the polished floor of a drawing room. After the crew murder the officers, Black Michael sets Lord and Lady Greystoke, together with abundant supplies and provisions, “alone upon … [the] wild and lonely shore,” castaways in a savage land.46

In this setting, English nobility and apes alike respond according to their innate abilities and what Burroughs understood as the nature of their sex. “I am but a woman,” Lady Alice admits, “seeing with my heart rather than my head, and all that I can see is too horrible, too unthinkable to put into words.” Lord Greystoke tries to stiffen her upper lip with the reminder that they carry within themselves both the blood of triumphant forebears and the brains of enlightened Victorians: “Hundreds of thousands of years ago our ancestors of the dim and distant past faced the same problems which we must face, possibly in these same primeval forests. That we are here today evidences their victory … . What they accomplished … with instruments and weapons of stone and bone, surely that may we accomplish also.” He erects a strong haven for their little family. Nonetheless, in the trauma of an attack by a bull ape, Lady Alice’s mind gives way. Throughout the first year of their baby son’s life (and the last of their own), she imagines them back in England and their time in Africa as merely a hideous dream. She dies as peacefully as a fading flower. Lord Greystoke, by contrast, is violently murdered by the huge king ape, Kerchak, who has led a cluster of apes to the Greystoke cabin. These apes belong to a species supposedly superior to the gorilla; yet

within it, as within the human species, Burroughs emphasized innate differences. Lacking nobility of character, intelligence, or appearance, Kerchak rules over his tribe by virtue of his immense strength and fierce temper: “His forehead was extremely low and receding, his eyes bloodshot, small and close set to his coarse, flat nose; his ears large and thin, but smaller than most of his kind.” By contrast, another member of the raiding party, the she-ape Kala, is “a splendid, clean-limbed animal, with a round, high forehead, which depicted more intelligence than most of her kind possessed.”47 Having just lost her offspring, she snatches the Clayton heir from the cradle and claims him for her own. In this way, Burroughs set up a plot with both mythic resonance and modern pertinence. When Kala becomes a mother to the noble waif, a host of issues rushes to the fore of Burroughs’s story: nature and nurture, primate affinities and human capacities, savagery and civilization.

Tarzan was the exemplary fictitious feral child of Burroughs’s and his readers’ time—as he has remained for the ninety years since. Although the fascination with them is age-old, “wild” children have exerted a special interest for Western societies since the eighteenth century, precisely because they seemed to offer special insight into the relationship between human nature and nurture. When, for example, “a naked, brownish, black-haired creature … about the size of a boy of twelve” emerged from the woods in northern Germany in 1724, the discovery was heralded as “more remarkable than the discovery of Uranus.” He appeared alert and seemed to have especially keen hearing and sense of smell. He did not care for clothes but gradually learned to wear them. Dubbed Wild Peter, he became the pet of the royal house of Hanover, then of the duke of Hanover, King George I of England, and subsequently of his daughter, Princess Caroline. The Scottish physician and writer John Arbuthnot eagerly examined him, hoping that Peter might learn to talk, relate his feral experiences, and thus communicate the nature of the human mind in a pure state, uncontaminated by society. Arbuthnot quickly concluded,

however, that Peter was an “imbecile,” incapable of speech due to severe mental retardation. 48

In 1799, seventy-five years after the discovery of Wild Peter, another feral boy of similar age was flushed by hunters in the forest near Aveyron in southern France. Like Peter, he was unaccustomed to clothes and did not speak; unlike Peter, he appeared dull rather than acute in all his senses, especially hearing and sight. The next year he was presented in Paris to the young physician Jean-Marc-Gaspard Itard, who became a pioneer in the education of the deaf and the mentally retarded. Although the Parisian public had flocked to the “savage of Aveyron” expecting to find in him the embodiment of Rousseau’s noble savage, Itard encountered someone quite different: “a disgustingly dirty child affected with spasmodic movements, and often convulsions, who swayed back and forth ceaselessly like certain animals in a zoo, who bit and scratched those who opposed him, who showed no affection for those who took care of him, and who was, in short, indifferent to everything and attentive to nothing.” Itard gave him the name Victor and sought to develop his senses, intellect, and emotions as well as to determine from his deficiencies what humankind owed to education and civilization. He spent five years in this effort, far longer than did Dr. Arbuthnot or any of Peter’s other examiners, and though Itard claimed some successes, Victor remained profoundly a captive of his stunted early life.49

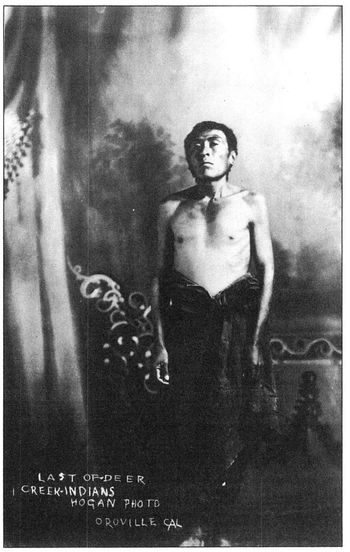

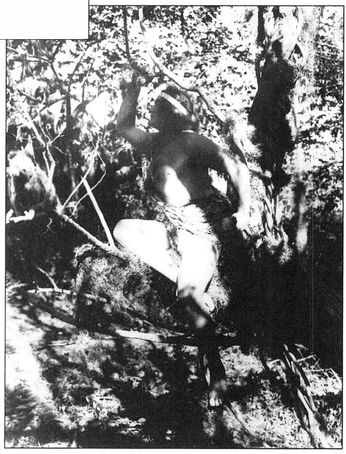

More immediate to Burroughs’s time than this pair of “wild” boys were a pair of “wild” men. At the end of August 1911, a few months before Burroughs began writing Tarzan, butchers at a slaughterhouse near Oroville in north-central California discovered a “wild” man cornered by their dogs. Superficially, at least, his situation resembled Wild Peter’s and Victor’s when they were found. Except for a ragged scrap of canvas, which he wore like a poncho, and a frayed undershirt, he was naked. He was also fatigued, frightened, and starving. And he spoke no language that his captors could recognize. He was not a boy of twelve, however, but a man who appeared perhaps sixty years old. (He was, in fact, about fifty.) But the greatest difference that immediately set his case apart from the feral children’s, long before his intelligence could be assessed or his emotional development determined, was race. When the local sheriff arrived, he perceived the “wild” man

as an Indian. To hold him and at the same time to shield him from the curious stares of people streaming to the jail at Oroville, the sheriff locked him up in a cell for the insane. Despite this setting, his appeared to be a striking case not of individual isolation and retardation, as with Wild Peter and Victor, but of cultural primitivism and isolation from the modern world. Newspapers trumpeted news of this last wild Indian, a figure who seemed to have stepped directly from the Stone Age into the age of airplanes.50

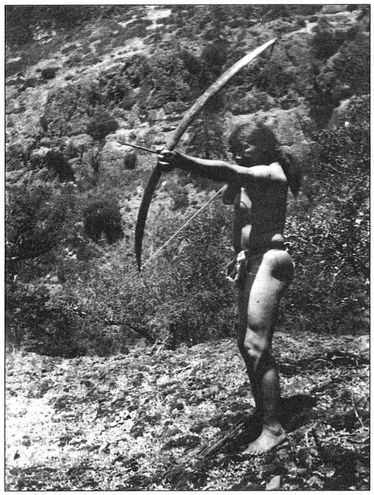

When Alfred Kroeber and Thomas Waterman, two anthropologists at the University of California at Berkeley, read these stories, they thought this “wild” man might be a survivor of the Yahi tribe whose last recorded members had been massacred almost a half century earlier. Two days after the “discovery” of the strange man, Waterman traveled to the Oroville jail. He sat in the inmate’s cell and read down a list of phonetically transcribed Yana words, until at last, with siunini, yellow pine, the man’s face lit up. He was, it gradually emerged, the last surviving member of the Yahi, a southern tribe of the Yana.51 Almost his entire life, he had lived in concealment as part of a tiny and ever dwindling remnant in the foothills of Mount Lassen. For three years, since the death of his mother, sister, and an old man, he had existed entirely on his own. Now he was officially a ward of the federal government. Wearing a shirt, coat, and trousers provided for him but spurning shoes, he traveled with Waterman by train and ferry from Oroville to San Francisco. Until his death from tuberculosis four and a half years later, he lived in the University of California’s new Anthropological Museum near Golden Gate Park, where he demonstrated Yahi crafts such as arrowhead making on Sunday afternoons and worked as a janitor’s assistant during the week. He never revealed his name, but Kroeber called him Ishi, which means man in Yana.

With his gentle, friendly disposition, Ishi played the role of Rousseauian noble savage far better than had Wild Peter or Victor. His reactions to modern civilization aroused keen interest. Traveling around San Francisco shortly after his arrival, he was unnerved by the crowds. The exclamation “Hansi saltu!” burst from his lips: “Many white people, many white people!”52 A few days later, a reporter invited Ishi to attend a vaudeville performance. From his box seat, during the first two acts, Ishi watched the audience exclusively, which to his mind was far more interesting than anything onstage. In time, he

learned white San Franciscans’ names for the people around him: “English, Chinaman, Japanese, Wild Indian, Nigger, Irishman, Dutchman, policeman.” He appeared impressed less with airplanes than with technologies nearer at hand and of direct use to him—matches, running water, roller window shades. According to those close to him, he blamed contemporary illnesses on “the excessive amount of time men spent cooped up in automobiles, in offices, and in their own houses. It is not a man’s nature to be too much indoors and especially in his own house with women constantly about,” he believed.53

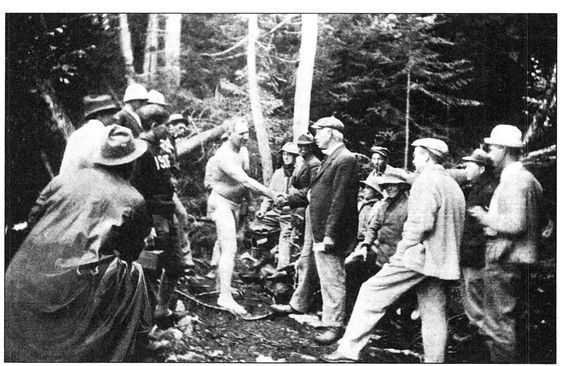

Ishi appealed to the modern longing for a more rugged, “primitive” existence that would revitalize masculinity. This longing emerged most vividly when he returned to his home ground in May 1914, almost three years after his emergence near Oroville. The impetus for the trip came not from Ishi, who was at first reluctant to revisit the place of his ancestors, but from Kroeber, and Waterman, and their physician-friend Saxon Pope. Ultimately, Ishi agreed, and the outing took on the aspect of a male-bonding retreat as much as an ethnographic study. Once back in his homeland, Ishi, who had refused to be photographed without Western dress in San Francisco, reverted to his native breechcloth. Still he refused to shed clothing entirely, even while swimming, unlike his “civilized” companions, all of whom reveled in their nakedness and the opportunity to “play Indian.” 54 As he demonstrated his great skills as hunter and fisherman and his deep reverence for the natural world, he seemed a time traveler from an ancient and alien realm.

Ishi in Oroville, California, August 1911. Photograph by

Hogan. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of

Anthropology. University of California at Berkeley

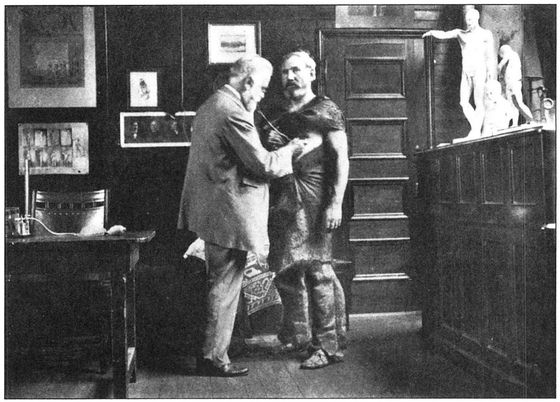

Ishi with bow and arrow. Deer Greek, 1914. Phoebe A. Hearst Museum of Anthropology. University of California at Berkeley

The desire to strip off civilization with one’s clothes and to experience primitive life firsthand in contact with nature was, of course, a masculine Romantic impulse that recurred with astonishing force and variety in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries—from

the French artist Paul Gauguin’s removal to Tahiti to the German nudist movement. In addition, at the time Ishi was discovered, millions of buttoned-up American boys and men were taking to the woods in organizations such as the Sierra Club and the Boy Scouts of America. Ernest Thompson Seton declared, in the first Boy Scout handbook, “Those live longest who live nearest to the ground, … who live the simple life of primitive times, divested, however, of the evils that ignorance in those times begot.” Seton proposed that everyone spend at least one month a year outdoors.55

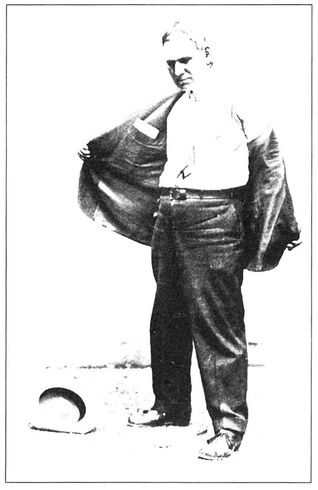

Perhaps the American figure who most grandiosely struck the primitivist pose in this period was a minor Boston illustrator, Joseph Knowles. Beginning in early August 1913, Knowles conducted an “experiment” that both reversed Ishi’s passage from wilderness to modern technological civilization and, more than any contemporary effort, paralleled Edgar Rice Burroughs’s literary experiment in Tarzan of the Apes. What Knowles proposed was to test whether a modern man, stripped naked and without any implements, could enter the woods and live the primitive life successfully, depending solely upon his own individual resources.56 The wilderness he chose was not in Equatorial Africa but in darkest Maine, and he was not a noble foundling but an experienced woodsman and guide on the eve of his forty-fourth birthday. Even so, the rather pudgy, cigarette smoking Knowles made an unlikely exemplar of savage virility. The surprising celebrity he achieved testifies to how much a public adapting to modern technological civilization craved the reassurance that the urban white man could face the elements on his own and triumph.

Knowles’s experiment recalls Sandow’s and Houdini’s feats, even as it resonates with Tarzan. Knowles sought the limelight as assiduously as any vaudevillian, though even he was dazzled by his success. As if conducting a Houdini escape, on August 4, 1913, he stripped off his clothes before reporters and photographers near the Spencer Mountains in northeastern Maine, vowing to stay in the wilderness for two months. He had arranged with the Boston Sunday Post to file weekly reports, written with charcoal on birch bark, chronicling his adventures. The week before, Harvard’s Dudley A. Sargent, the physical-culture expert who twenty years earlier accorded Sandow the title “perfect man,” had examined him. The best Sargent could say

was that Knowles “showed considerable fat, which will aid him in resisting cold.” Still, the doctor struck exactly the note of cultural urgency that Knowles desired: “There is no question that in our advancement from primeval life we have dropped through disuse a great deal of natural knowledge; our artificial life has robbed us of some of our greatest powers and has stunted others.” Under the circumstances, he applauded Knowles’s “attempt to live like a primeval man” as being of both scientific interest and practical value.57

Joseph Knowles stripping for his wilderness experiment, 1913. From Alone in the Wilderness. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Knowles bidding his friends goodbye. From Alone in the Wilderness. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Over the next two months, the activities of the “forest man” became headline news in the Boston Post. Readers learned of his struggle to build a fire, catch trout, and contrive leggings out of moss. On August 24, the Post excitedly titled his dispatch “Knowles Catches Bear in Pit.” The painter turned primitivist furnished readers with a blow-by-blow description of how he caught and killed a young black bear so that he might have its skin as a covering at night and as clothing when he finally reemerged to civilization. Later, he reported how he killed a small deer, grabbing it by its horns and breaking its neck. These exploits were double-edged. On the one hand, they testified to Knowles’s prowess as primordial man, recapitulating the Darwinian struggle by which his ancestors had ascended the ladder of civilization. (“In the wilderness,” he declared, “the one great law is the survival of the fittest.”58) On the other hand, these kills violated the Maine game laws, from which Knowles had unsuccessfully sought an exemption. During his last weeks, he grew worried that game wardens might seek him out and arrest him; he spent his last days in the wild fleeing across the Canadian border so that he would not be taken prematurely.

When, scratched, bruised, thirty pounds lighter, and garbed in animal skins, Knowles emerged on October 4 near Megantic, in Quebec, he looked like primordial man come to life. He seemed to have transformed his very race in the process: a reporter described him as “tanned like an Indian, almost black.” The size and enthusiasm of the waiting crowd stunned him. When he came down the steps from his train, he thought the horde “would tear the skins from [his] body.” It was a foretaste of the tremendous receptions to come. All the way through Maine and down to Boston, crowds cheered his passage. Schools released their charges so that they might glimpse the great man. When he arrived in Boston, once again clad in animal skins,

crowds mobbed him. For a celebration on Boston, Common, they swelled to an estimated fifteen to twenty thousand people. At Harvard, Dr. Sargent examined Knowles again and pronounced him stronger in every respect than before he entered the woods. Afterward, the staff of Filene’s Men’s Store promised to turn him into a modern man once more through “barbering, manicuring, chiropody and complete outfitting in new and fashionable clothes.”

Knowles in wilderness garb as examined by Dudley A. Sargent,. From Alone in the Wilderness. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Knowles’s metamorphoses from civilized to primitive man and back again seemed to fascinate the public as much as had Houdini’s great magical metamorphoses. At a lavish banquet honoring Knowles, Sargent declared, “A dress shirt is not becoming to him with such a splendid body hidden away underneath.” Yet it was Knowles’s ability to inhabit both worlds that captured the public’s imagination. He served as a primitive proxy for modern men, who liked to imagine that they, too, had splendid bodies hidden underneath their dress shirts. Two months after his return, he completed a book based on his dispatches to the Post called Alone in the Wilderness. A rival newspaper, William Randolph Hearst’s Boston American, charged that Knowles

was a fraud who actually bought his celebrated bearskin and slept in a snug, secret cabin while in the woods, but it failed to prick the bubble of his celebrity. Knowles briefly toured on the vaudeville circuit retelling his feat, and his book sold 300,000 copies.59

Burroughs’s “wild child” was of course a fictional hero in an adventure story rather than a historical object of scientific examination. It is doubtful that Burroughs knew of Wild Peter, Victor, or other feral children when he wrote Tarzan. Nor does he appear to have been aware of Ishi or, in the interval between Tarzan’s publication in The All-Story and in book form, to have remarked on the feat of Joseph Knowles. As he later said, the legend of Romulus and Remus suckled by a wolf and of Kipling’s animal stories came more to his mind.60 In time, Burroughs did learn more about the fate of feral children and acknowledged that Tarzan’s adventures were fictional entertainments, not literal possibilities. He wrote in 1927:

I do not believe that any human infant or child, unprotected by adults of its own species, could survive a fortnight in such an African environment as I describe in the Tarzan stories, and if he did, he would develop into a cunning, cowardly beast, as he would have to spend most of his waking hours fleeing for his life. He would be under-developed from lack of proper and sufficient nourishment, from exposure to the inclemencies of the weather, and from lack of sufficient restful sleep.

Burroughs intended Tarzan as “merely an interesting experiment in the mental laboratory which we call imagination.”61

Even with this retrospective caveat, Burroughs’s story could be read in two alternative yet overlapping ways. It might be understood, first, as a novel diversion, an experiment in storytelling that aimed only to entertain. At the same time, Tarzan could be read as an allegory that in miniature recounted and explained why its hero (and those like him) triumphed where others failed. In this sense, the workings of the narrative revealed truths about the reader’s world, not

just the fictional characters’. Although he denied that the events in his imaginative laboratory could literally happen (which many a reader of Tarzan has contested), Burroughs still permitted a considerable area within which the story might be understood to be true.62

In this imaginative laboratory, Burroughs created a figure whose hereditary advantages, as he conceived them, are severely tested in the harsh environment of the African jungle. At the outset his situation in some ways reverses that of Wild Peter and of Victor. Apes rather than cultured savants regard him as developmentally backward, and both his foster father, Tublat, and the tribal leader, Kerchak, argue that he should be abandoned as hopeless. By the age of ten, he can claim some accomplishments, including superior cunning and ability on the ground, but he remains ashamed of his deficiencies, such as his hairless body, “pinched nose,” and “puny white teeth.”63 The name the apes give him marks his difference (and, ultimately, Burroughs believed, his superiority): Tarzan means white skin.

In this way Burroughs sought to test the nature of white Anglo-Saxon masculinity. A literary fantasy rather than a scientific inquiry, Tarzan nonetheless resonated with the social and natural sciences of the day, which were, of course, much more deeply implicated in Western cultural fantasies than their practitioners realized. What was the nature of the human species, and how was it related to other higher primates? And within the human species, was modern Anglo-Saxon man’s putative superiority intrinsic (biological) or extrinsic (the product of collective social and cultural achievements)? Taken out of their environments, how would modern man fare in the wild and “primitive” man fare in modern civilization? Was primitive man, as exemplified by Ishi, passing with the rise of modern civilization? Or was the racial stock that had created modern man in the first place passing? This last view was exemplified by Theodore Roosevelt’s dire warnings of “race suicide” and Madison Grant’s still more extremist The Passing of the Great Race (1916).64 Each view—and at times a combination of both—was widely embraced by European and American scientists at the time. Relations between humans and their fellow primates and between modern and “primitive” man were especially topical when Burroughs was writing.

In many respects, interest in higher primates picked up where interest in feral children left off. (Indeed, both etymologically and biologically,

the line between the two frequently blurred.65) Especially after the publication of Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species (1859) and The Descent of Man (1871), determining human nature became intimately connected with humanity’s relation to fellow primates and their ongoing struggle for existence. What was distinctively human, it appeared, could be illuminated by determining what was common to members of the primate order. How human beings learned could be clarified by discovering how other primates learned in the wild—and, perhaps, in the laboratory. Comparisons were hampered, however, by the difficulty Western scientists experienced in studying chimpanzees and especially gorillas, which were hard to locate, capture, tame, and maintain in captivity.

A pioneering effort in this regard was made by Richard L. Garner, an early researcher of animal speech who claimed to have observed more chimpanzees and gorillas in their natural state than any other white man. In his desire to forge intellectual and emotional links with these primates—and in his persistent adherence to racial categories—he provides to some degree a flesh-and-blood anticipation of Tarzan. Garner, who was born in Virginia in 1848, declared, “From childhood, I have believed that all kinds of animals have some mode of speech by which they can talk among their own kind, and I have often wondered why man has never tried to learn it.”66 Largely on his own, in 1884 he started to study the speech of monkeys and the comparatively few apes (including orangutans, gibbons, gorillas, and chimpanzees) available in American zoological gardens and circuses. He conceived of this task “as very much the same as learning [the speech] of some strange race of mankind—more difficult in the degree of its inferiority, but less in volume.”67 In this effort he made the first phonograph recordings of monkeys and played them to other monkeys to observe their reactions. Reasoning that the primates with the greatest physical development would display the greatest linguistic development as well, he set sail in 1892 for what was then French Gabon and French Congo in Equatorial Africa to study chimpanzees and gorillas “in a state of freedom.”68

To discover firsthand how chimpanzees and gorillas behaved in the wild, outside human cages, Garner placed himself in a cage. He built a small cubicle, six feet six inches on each side, out of steel mesh, painted it a dingy green, covered it with bamboo leaves, and

dubbed it “Fort Gorilla.”69 For 112 days in 1893, he made observations from this outpost. He did not prove so inconspicuous as he had hoped, however, and ultimately he had to rely on secondhand reports to augment his researches.