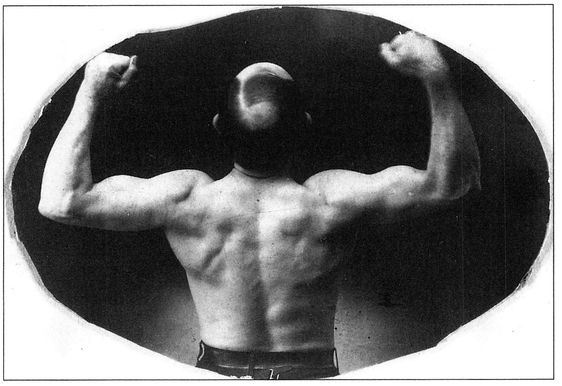

In 1904 a balding, compactly built banker in Muncie, Indiana, posed for the camera on his forty-fifth birthday. It was not a conventional birthday portrait, however. For the occasion he stripped to the waist, flexed his biceps, and had himself photographed from behind. His business life was sedentary, but during the next forty years he kept up various physical regimens, ranging from lifting light weights to deep-breathing exercises. His name was Albert G. Matthews, and he was my great-grandfather; he died nine days before I was born.

I first saw this portrait in a family album as a child, and it prompted questions that fascinate me still. My initial response was surprise: What was he doing? Other male relatives in photographs showed their bodies, if at all, only in swim trunks as they squinted at the camera, usually holding a fish. Later I wondered, What was his sense of his body, and how was it shaped by the technologies and culture of his time? What models of strength did he admire? What dreams and anxieties did this image contain? Family photographs were one of the earliest ways by which I learned the importance of visual evidence in history, and in retrospect, I can see that this photograph was the first historical fragment that led to this book.

Many years later, I sifted through some thirteen thousand photographs

at Harvard University devoted to the most famous of all Albert Matthews’s contemporaries (ten months his senior), the man who was president when his birthday portrait was made in 1904, Theodore Roosevelt. Here the sense of theatricality that I had first glimpsed with my ancestor burst forth on a colossal scale. Crucial to Roosevelt’s success was his ability to turn prized characteristics of manliness into spectacle, literally to embody them. The camera and the pen were essential aids in that effort. Born in 1858 to one of the richest and most socially prominent families in New York, Roosevelt created his own stirring drama of childhood adversity overcome in an account of how he transformed his “sickly, delicate,” asthmatic body into the two-hundred-pound muscular, barrel-chested figure of a supremely strong and energetic leader. His Autobiography, first published in 1913, included illustration of Roosevelt in positions of executive authority (assistant secretary of the navy, governor of New York, president of the United States) carefully balanced with portraits of him active and outdoors (on horseback, returning from a bear hunt in Colorado, with hand on hip as Rough Rider colonel in the Spanish-American War, and holding a rifle “in winter riding costume”).1

Albert G. Matthews on his forty-fifth birthday. 1904

The photographic archive showed that Roosevelt had practiced

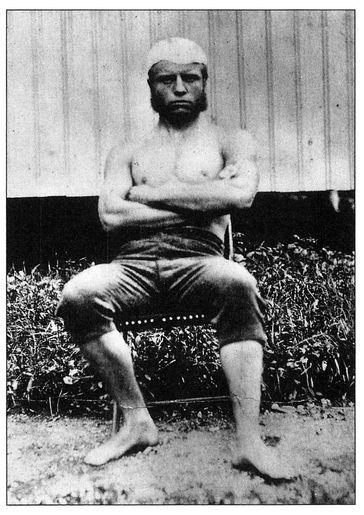

such poses assiduously, and no American of his generation or president before or since—not Lincoln, not Kennedy, not Reagan—developed a broader repertoire. Once past his childhood, when he was pictured in the unisex white dress, long hair, and bonnet worn by upper-class children of the time, he seems to have determined never to appear before the camera in a pampered guise again. In a routine physical examination as a Harvard undergraduate, he learned from Dr. Dudley A. Sargent, the college physician and the nation’s leading authority on physical education, that he had “heart trouble” and should lead a sedentary life, taking care not even to run up stairs. Roosevelt replied that he could not bear to live that way and intended to do precisely the opposite.2 A photograph from about this time shows him outside the Harvard boathouse wearing rowing togs, bare-chested and barefoot, his jaws filled out with a beard, his biceps bulged by his fists.

Theodore Roosevelt as a Harvard undergraduate in rowing attire. Theodore Roosevelt Collection. Harvard College Library

From his college days to the end of his life, Roosevelt appears to have considered no hunting trip complete without recording it either in the field or in a photographer’s studio. For his first book, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman (1885), based on his adventures in the Dakota Territory, he struck various attitudes, holding a rifle and wearing a fringed buckskin outfit in the style of Buffalo Bill and sporting the holsters, pistols, chaps, and broad-brimmed hat of the ranchman. In 1898, upon his return from Cuba, where he had led his regiment of Rough Riders in victorious charges up Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill, he instantly memorialized his achievements in portraits that displayed a commanding martial bearing. In 1904, the year my great-grandfather posed for his birthday portrait, Roosevelt repeatedly jumped a fence on horseback until a Harper’s Weekly photographer caught just the right dynamic image for the upcoming presidential campaign.3 After his presidency, a stage of life in which most of his successors have done nothing more strenuous than golf, he threw himself into new activities—with photographers always at the ready. He recorded his exploits as big-game hunter and explorer (including obligatory poses with animal trophies) in Africa in 1909. Four years later, after his fiercely energetic but unsuccessful “Bull Moose” campaign against William Howard Taft and Woodrow Wilson, he headed for uncharted wilderness and big game once again, this time in Brazil, where he nearly lost his life. He spent his last years, also before the camera, stumping on behalf of the U.S. military effort during the Great War and itching to be in the thick of battle himself.

Many historians exploring manliness in this period have stopped with Roosevelt. But my pursuit has taken me further. And it has led to three immensely popular artists who entertained Americans in the two decades between 1893 and 1914: the strongman Eugen Sandow (1867–1925), the escape artist Harry Houdini (1874–1926), and the author of Tarzan of the Apes, Edgar Rice Burroughs (1875–1950). Sandow, Houdini, and Burroughs’s Tarzan all acquired immense national and international fame. They literally became part of our language, which suggests that the cultural need for the metaphors they supplied was great, as was the power with which they entered into the lives of their audiences. Viewed in conjunction, these figures assume still greater significance: they expressed with special force and

clarity important changes in the popular display of the white male body and in the challenges men faced in modern life.

Although Sandow’s name is no longer a household word, he is still revered as the father of modern bodybuilding and a pioneer of physical culture. In his heyday as a vaudeville performer, his position was even more exalted. Physical-fitness experts and journalists alike hailed him as the “perfect man,” and his unclad body became the most famous in the world. He established a new paradigm of muscular development and attracted countless followers, ranging from the reformed “ninety-seven-pound weakling” Charles Atlas to the poet William Butler Yeats. His significance for cultural history is still greater. His display of his physique provides a fresh point by which we can assess the changing standards of male strength and beauty that may have inspired men like Albert Matthews to inspect their own bodies in private.

Sandow’s celebrity has faded, but Houdini’s hold on the popular imagination remains strong even today, though the nature of his feats and the context of his career have been obscured. For the general public, his name dominates the history of magic—to the intense annoyance of many conjurers and magic historians, who rank others superior. Wildly erroneous myths about him persist, such as that he died performing his “Chinese Water Torture Cell” escape (as does Tony Curtis’s character in the 1953 Paramount film Houdini). Meanwhile, there has been little effort to place him in full historical and cultural context as not only the most brilliant escape artist in the history of illusion but also a magus of manliness, known for some of the most audacious displays of the male body in his time.

Burroughs’s fictional character Tarzan is best known of all, but, again, in ways that obscure the significance of his creation. As the subject of twenty-four books written by Burroughs over thirty-five years, and of roughly fifty films, four major television series, a radio serial, and comic books, Tarzan and his adventures have been adapted in ways that hardly resemble the original. The persistence of his popularity testifies to enduring cultural fantasies about manly freedom and wildness. And an examination of the cultural milieu at his first appearance in Frank Munsey’s All-Story magazine in 1912 illuminates important, if forgotten, aspects of American life a century

ago. It reveals why a story about an immensely strong, incomparably free, indomitably wild noble savage could so entrance men who felt locked in the “iron cage” of modern urban, corporate life.4

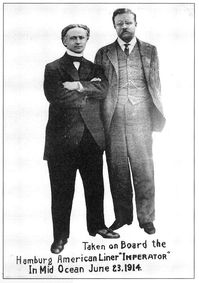

The spectacles of the male body mounted by these three figures built on values embodied in men such as Theodore Roosevelt. In fact, at various points in their careers, all three sought to associate themselves directly with Roosevelt. As a confused young man in 1898, Burroughs wrote to Roosevelt to volunteer for the Rough Riders; he received a gracious but firm refusal. In 1905, at the height of his international prestige, Sandow met with Roosevelt, then president, to discuss their mutual support of the physical-fitness cause. As for Houdini, after entertaining the ex-president on a transatlantic voyage in 1914, he eagerly distributed hundreds of copies of a photograph of himself and his new “pal,” in which five other men had been carefully airbrushed away.5

Nonetheless, the popular spectacles created by Sandow, Houdini, and Burroughs take us far beyond Roosevelt’s performances of manliness, expressing even deeper fantasies and anxieties. All three laid great stress on the unclad male body in ways that Roosevelt would have found unimaginable. This element was crucial to their novelty and impact. They contributed to a new popular interest in the male nude as a symbol of ideals in peril and a promise of their supremacy, as a monument to strength and a symbol of vulnerability, as an emblem of discipline and an invitation to erotic fantasy. In the guise of entertaining, they reasserted the primacy of the white male body against a host of challenges that might weaken, confine, or tame it. Popular spectacles of the female body in this period usually revolved around issues of subordination and transgression, but the overriding theme for these three men concerned metamorphosis. They repeatedly dramatized the transformation from weakness to supreme strength, from vulnerability to triumph, from anonymity to heroism, from the confinement of modern life to the recovery of freedom.

These images of manliness were obviously images of whiteness as well. Neither Sandow, nor Houdini, nor Burroughs was a racial extremist by the lights of his era, any more than Roosevelt himself, who famously invited Booker T. Washington to dine with him at the White House (and infamously issued dishonorable discharges to 170 African American soldiers in the “Brownsville affair”). Yet like Roosevelt, all

three shared—and to various degrees contributed to—the highly racialized views that mark and mar this period. In science, popular literature, art, and daily life, the bodies of African American and Native American men had been frequently displayed, even fetishized, while their dignity and worth were denied. Significantly, the popular exaltation of the white male body took place at the very time when Plains Indians, supposedly a “vanishing race” following the massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890, were forced onto reservations little better than prisons and African Americans were brutally subjected to segregation, disfranchisement, and lynchings. It is as if white American men sought to seize the “primitive” strength, freedom, wildness, and eroticism that they ascribed to these darker bodies to arm themselves for modern life.

Harry Houdini and Theodore Roosevelt on board the liner

Imperator, June 1914 …

… with their fellow passengers. Library of Congress

Manliness is a cultural site that is always under construction, of course, but in this period it seems to have been undermined on a number of fronts and demanded constant work in new arenas to remain strong. Many men born too late for the Civil War wondered how they would fare in a similar test of courage, and some, like Roosevelt, plunged into the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars as opportunities to prove themselves and to build American manhood.6 Alarmed by the “new immigration” from southern and eastern Europe, composed principally of Catholics and Jews, some Americans worried that the “enterprising, thrifty, alert, adventurous, and courageous” immigrants of past generations were being replaced by “beaten men from beaten races; representing the worst failures in the struggle for existence.”7 At the same time, reports warned that Americans of Anglo-Saxon stock were declining markedly in physical vigor and, by failing to reproduce themselves in sufficient numbers, might ultimately commit “race suicide.”8 Keenly aware of the passing of the frontier, many Americans believed that a nation of farmers was rapidly becoming a nation of city dwellers. Roosevelt’s fervent commitment to conservation represented one attempt among many to stay close to the wild lest it be extinguished. Even those such as he who occupied the most privileged positions often worried that society’s comforts might weaken their bodies and their wills. Anglo-Saxon Protestants from refined and intellectually cultivated classes were thought to be especially susceptible to neurasthenia, that distinctively modern, characteristically American disease of nervous weakness

and fatigue. The founder of this medical specialty, George M. Beard, placed high among its manifold causes excessive brain work, intense competition, constant hurry, rapid communications, the ubiquitous rhythm and din of technology. At the turn of the century, neurasthenia appeared to be reaching epidemic proportions.9

Above all, perceptions of manliness were drastically altered by the new dynamics created by vast corporate power and immense concentrations of wealth. Fundamental to traditional conceptions of American manhood had been autonomy and independence, which had to be recast in a tightly integrated economy of national and international markets. Titanic corporations arose with incredible swiftness in all areas of industry: Standard Oil, United States Steel, Pennsylvania Railroad, General Electric, Consolidated Coal, American Telephone and Telegraph, International Harvester, Weyerhaeuser Timber, U.S. Rubber, Pittsburgh Plate Glass, International Paper, Du Pont de Nemours, American Sugar Refining, Armour, United Fruit, American Can, Central Leather, and Eastman Kodak. By 1904, about three hundred industrial corporations had gained control of more than 40 percent of all manufacturing in the United States.10

And at the head of these new companies stood a greatly expanded, highly bureaucratized managerial class. Clerical workers, no more than 1 percent of the workforce in 1870, had swelled to more than 3 percent by 1900 and nearly 4 percent by 1910. These nascent “organization men” (and some women) increasingly worked in large buildings where the offices were as hierarchical and rule-bound as armies. A writer in The Independent worried, “The middle class is becoming a salaried class, and rapidly losing the economic and moral independence of former days.”11

Factory workers, for their part, were the foot soldiers in this expanding industrial force. The period 1890–1914 was pivotal in the struggle between them and management over control of production within factories. Skilled workers had treasured a certain autonomy in setting the pace, organization, and distribution of wages for their work, an autonomy they had earned because of their superior knowledge of their craft. As Big Bill Haywood of the Industrial Workers of the World liked to boast: “The manager’s brains are under the workman’s cap.”12 The new corporate industrial order massively assaulted this power and the ethic of manly pride and brotherhood among

workers that sustained it. Through intense mechanization, division of labor, and “scientific management,” industrialists endeavored to dominate all aspects of production and to reduce the workers’ bodies to components in a gigantic machine.

Americans were in the forefront of this corporate revolution. Whereas in 1870 Britain provided 32 percent of the world’s industrial output (followed by the United States at 23 percent and Germany at 13 percent), in 1913 the United States provided an immense 36 percent (Germany and Britain distantly trailed at 16 percent and 14 percent, respectively).13 Yet to contemporaries, this industrial growth felt not like an orderly process but like a wild, careening ride. Wall Street panics in 1873 and 1893 began two of the greatest depressions in American history, and smaller depressions in 1885 and 1907 jolted the economy. By the mid-1880s supporters of labor and capital alike had come to fear that the strains of the new industrial society might erupt in large-scale riots, even a class-based civil war.

Industrialization accelerated major demographic shifts that were also altering the arenas in which manliness might be exercised. The nation’s population continued to be the fastest growing in the world, leaping from fewer than forty million in 1870 to roughly sixty-three million in 1890 and nearly ninety-two million in 1910. This increase was partly due to unprecedented numbers of immigrants, amounting to 16 percent of the population in 1881–1900 and a staggering 24 percent in 1901–1920.14 The new arrivals clustered mostly in America’s cities, particularly along the manufacturing belt from the Northeast to the upper Midwest. In 1910 in New York, Chicago, Boston, Cleveland, Detroit, and Providence, more than one in three residents was foreign-born.15

Yet even as the population grew, more and more men deferred marriage; in fact, one historian has called this period “the age of the bachelor.” In 1890 an estimated two-thirds of all men aged fifteen to thirty-four were unmarried, a proportion that changed little through the first two decades of the twentieth century. In cities the proportion was higher still, forming the basis for a flourishing urban bachelor culture that included a growing gay subculture. In many respects, this bachelor culture represented a pocket of resistance to—or at least a refuge from—the responsibilities of family and community, the demands of women, the discipline of work, and the pressures of a more

regulated society. In boisterous play and aggressive competition, bachelors could enjoy a continuity between boyhood and manhood. They played or watched sports and reveled in contests of physical skill and decisive triumph. At the beginning of this period, their great hero was no exponent of manly rectitude such as Roosevelt became, but boxing’s brawling heavyweight champion John L. Sullivan. In newspapers and pulp fiction, they avidly read adventure stories about other heroic men, from Eugen Sandow to Tarzan. Many also indulged in pursuits that more respectable elements condemned: heavy drinking, swearing, gambling, engaging in casual sex with women—or other men.16

These urban bachelors had several female counterparts, including the working-class “tough girl,” the radical needleworker, the shop clerk, the typist, and the “New Woman.” The last was a capacious term for middle- and upper-class women who in various ways conducted themselves with a new independence and assertiveness, whether by shopping in department stores, smoking in public, playing tennis, expressing interest in sexuality, earning advanced degrees, entering traditionally male professions, calling for social and political reforms, or agitating for the ballot. Self-development, not self-sacrifice, was the New Woman’s watchword. As one woman writer succinctly put it, “The question now is, not ‘What does man like?’ but ‘What does woman prefer?’” Although neither the term “feminism” nor its full expression emerged until the end of this period, it was already clear that many women were refusing to be bound by traditional notions of women’s domestic sphere.17

As the structure of both work and urban life changed dramatically, so too did the forms of leisure and communications by which people found release from and perspective on their worlds. Many commercial enterprises offered attractions calculated to appeal to broad popular tastes across different classes, ethnicities, and genders, and they grew into big businesses with some of the same characteristics of systematization, centralization, and managerial control that defined corporate industries. As they intersected, they created the conditions for a new society of spectacle that seemed to ease some of the deep divisions in America’s new urban, industrial life. It is here that Sandow, Houdini, and Burroughs flourished.

Vaudeville theater, one of the most popular new entertainments

and the springboard for both Sandow’s and Houdini’s careers, emerged in the 1880s. It represented an extraordinarily successful effort to unite a fragmented theatergoing public: it combined the format of the variety show with standards of morality and settings of refinement that placed it decisively apart from the concert saloons and burlesque houses where variety shows had flourished. With as many as ten or twelve acts, sometimes in continuous performance throughout the day, vaudeville triumphed by offering “something for everyone.” “If one objects to the perilous feats of the acrobats or jugglers,” observed a critic in 1899, “he can read his programme or shut his eyes for a few moments and he will be compensated by some sweet bell-ringing or sentimental or comic song, graceful or grotesque dancing, a one-act farce, trained animals, legerdemain, impersonations, clay modeling, the biograph [moving] pictures, or the stories of the comic monologuist.”18 Whether in small-time houses or big-time theaters, vaudeville performers prided themselves on being able to engage diverse audiences of men, women, and children from both working-class and middle-class backgrounds in cities and towns across America. Even so, theirs was an industrialized art in which the vaudevillians worked along regional circuits that were dominated after 1900 by the United Booking Office, which spanned the continent.

Sport experienced a similar transformation into commercial entertainment. As once local, informal, and unregulated games became big business, they were systematized and put under managerial control. Yet they did not succumb to bureaucratic rationalization; the most popular sports, boxing and baseball, offered stirring dramas of individual prowess and communal aspiration that some fans treasured for their lifetimes. These professional sports, as well as college football, were heavily freighted with ambitions to revitalize American manhood. Even while seeking to reform their abuses, elite spokesmen extolled the value of these sports in instilling strength, skill, toughness, endurance, and courage. Writing in the dignified pages of The North American Review in 1888, Duffield Osborne simultaneously advocated replacing bare-knuckle fighting with regulated glove boxing and defended pugilism, with its “high manly qualities,” as a bulwark against the emasculating tendencies of modern life. Without such antidotes to “mawkish sentimentality,” he warned, civilization would degenerate into “mere womanishness.”19 Four years later,

“Gentleman Jim” Corbett defeated John L. Sullivan in the first heavyweight championship bout fought with padded gloves and timed rounds under the Marquis of Queensberry Rules. When the African American Jack Johnson won the title in 1908, however, it became abundantly clear that many fans thought revitalization should be for whites only. They raised an insistent call for a “Great White Hope” who could defeat Johnson, which was finally answered by the hulking Jess Willard in 1915.20

The transformations in popular theater and sport were sustained by profound changes in journalism. In the country as a whole from 1892 to 1914, the number of daily newspapers rose by more than a third, from 1,650 to 2,250, an all-time high; and their size expanded and circulation doubled. In the vanguard of change marched the great metropolitan newspapers. In 1892 ten papers in four cities had circulation bases higher than 100,000; in 1914 more than thirty papers in a dozen cities could make such a claim. Publishers, led by Joseph Pulitzer and William Randolph Hearst, increasingly encouraged the practice of what was called the New Journalism, by which they hoped to attract as diverse a readership as possible. They offered at low prices a bulging combination of sensational stories (such as those about Houdini’s flamboyant escapes), serious news coverage, reportorial stunts, personal interviews (often with vaudeville and sports celebrities), civic crusades, and lavish illustrations. When newspapers were organized into spaces and departments devoted to sports, fashion, Sunday magazine supplements, and special columns, they acquired a variety format that resembled a vaudeville bill. And like vaudeville, these newspapers self-consciously aspired to be the “voice of the city,” speaking for as well as to its myriad residents. They expressed this ambition both in their publications and, frequently, in their very offices, exemplified by the Pulitzer Building, which, upon its completion in 1890, surpassed Trinity Church as the tallest structure in New York City.21

The birth of the modern metropolitan daily and Sunday newspaper was accompanied by that of the modern, low-priced, mass-circulation magazine. Previously, inexpensive magazines had enjoyed only fleeting success. But in 1893 S. S. McClure founded an illustrated monthly magazine bearing his name that offered both fiction and articles and sold for only fifteen cents rather than the thirty-five

charged by his self-consciously genteel rivals. Other magazines, such as Cosmopolitan and Munsey’s, cut their prices still further, and a host of new ten-cent magazines followed in their wake. In 1896, on the strength of his success, Frank Munsey revamped his story weekly, The Argosy, printed it on cheap, porous wood-pulp paper, and launched the modern pulp-fiction magazine. In the next few years he created a stable of such magazines, including The All-Story, in which Tarzan first appeared. By 1903 Munsey, could fairly estimate that the ten-cent magazines had gained 85 percent of the entire magazine circulation in the country. Offering a wide variety of stories and articles, abundant illustrations, and a lively tone, such magazines represented a significant cultural challenge to established competitors. The editor of The Independent snobbishly defended his magazine’s concentration on the “comparatively cultivated class” in magazines and newspapers, saying it was “the only audience worth addressing, for it contains the thinking people.” But publishers such as McClure, Munsey, Pulitzer, and Hearst, like vaudeville impresarios such as B. F. Keith and F. F. Proctor, staked their fortunes on their ability to hold a mass following by giving the people plenty of varied materials at low prices.22

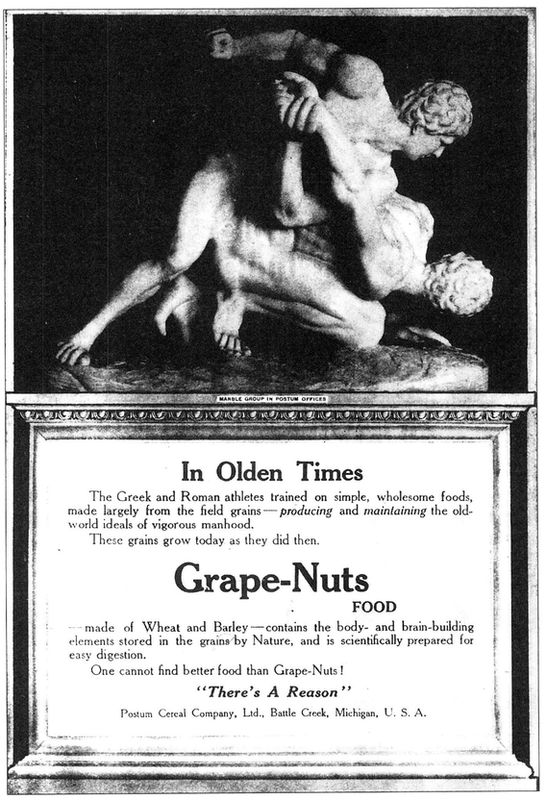

A number of factors held down the costs of mass-circulation magazines and newspapers, including technological breakthroughs in papermaking, typesetting, printing, and binding. But in their development, revenues from advertising were indispensable. Between 1892 and 1914 advertising in newspapers and periodicals increased by roughly 350 percent, and most of it was from local sources, especially the new department stores. Yet magazines, long the messengers for correspondence courses and patent nostrums, now were key sites for national advertising of standard brands from Victrolas to Grape-Nuts. Older “polite” magazines had once prided themselves on avoiding advertising, but for mass-circulation magazines in the early twentieth century the situation was fundamentally different. “There is still an illusion to the effect that a magazine is a periodical in which advertising is incidental,” explained an advertising executive in 1907. “But we don’t look at it that way. A magazine is simply a device to induce people to read advertising.”23

Associated with these transformations in the popular theater, sports, and the press, as well as with the expansive commercial culture as a whole, was the continuing proliferation of photographic images.

The passion for studio portraits, awakened with the rise of photography, not only seized people of all classes but helped to make possible a new celebrity culture. Innovations in photographic reproduction and display changed individuals’ very apprehension of themselves and the world. In 1888 George Eastman introduced his Kodak camera, initially a toy for the wealthy but a device that quickly demonstrated its potential to make virtually everyone an amateur photographer. At about the same time, between 1885 and 1910, the halftone, a new, cheaper technique of photoengraving that permitted the direct reproduction of photographs in newspapers, magazines, and books, effected a visual revolution.24 Finally, the new mass medium of the movies grew with dazzling speed from Thomas Edison’s peephole kinetoscope of 1893 (in which Sandow made an appearance), to large-scale motion-picture projection in 1896 (which was frequently the concluding diversion on vaudeville programs), to D. W. Griffith’s controversial two-and-a-half-hour epic of white supremacy, The Birth of a Nation, in 1915. What had begun as a novelty became a consuming national pastime.

Recovering classical manhood through Grape-Nuts, an advertisement in The All-Story, December 1911. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

These popular spectacles were crucial in both maintaining and subverting gender categories. Indeed, one of the most striking elements was that men’s and women’s bodies were displayed and dramatized as never before in popular theater, sports, photography, fiction, film, and advertisements. Recent studies have highlighted aspects of this process, especially as it affected women. In the popular theater, for example, spectacle could be used to address quite different audiences for vastly different purposes. Burlesque, expelled from “legitimate” theaters and vaudeville houses, offered leg shows for working-class and lower-middle-class men. By contrast, vaudeville theaters, looking to attract middle-class families as well as members of the bachelor subculture, offered women a broader range of roles. Many of these were constraining, but others allowed for freedom, independence, and self-expression that laid the groundwork for an emergent feminism. By the second decade of the twentieth century, protesting women, including socialists, trade unionists, and suffragists, had taken this sense of theatricality from the stage to the streets to gather support for their causes.25

Historians have paid less attention to the importance of the male body in popular spectacles—and, especially, challenges to the exposed

white male body—as expressing the meaning of manliness in this emergent urban, industrial order. That subject lies at the heart of this book. My approach is highly selective. I have chosen to focus on Sandow, Houdini, and Burroughs in order to see how they reveal popular aesthetic and cultural patterns. In a context dominated by the rise of corporate capitalism, the changing character of work, the advent of a skyscraper civilization, and the emergence of the New Woman, they helped to create the Revitalized Man. As a model of wholeness and strength, this figure ostensibly stood above the political conflict and class strife of the period, inviting a broad and diverse public of men and women, blue-collar and white-collar workers, to celebrate common gender ideals. The appeal of Sandow, Houdini, and Tarzan could unite followers of John L. Sullivan and Theodore Roosevelt; readers of newspapers as diverse as Richard Kyle Fox’s National Police Gazette, Hearst’s and Pulitzer’s metropolitan dailies, and the socialist Masses; admirers of Burt L. Standish’s Frank Merriwell at Yale and Jack London’s The Call of the Wild; and fans of the illustrator J. C. Leyendecker’s Arrow Collar Man and the painter George Bellows’s savage boxers.

Sandow, Houdini, and Burroughs’s Tarzan can thus illuminate much about the place of popular culture at the advent of modern society. They help us to understand more about how the shift to an advancing technological civilization was communicated to and apprehended by publics in North America and abroad. They tell us about how modernity was understood in terms of the body and how the white male body became a powerful symbol by which to dramatize modernity’s impact and how to resist it. They reveal the degree to which thinking about masculinity in this period meant thinking about sexual and racial dominance as well. They also tell us that hopes and fears, aspirations and anxieties are often difficult to distinguish. Perhaps every dream is the sunny side of some nightmare; perhaps every cultural wish has a dark lining of fear.