5G | BARCODES AND RFID TAGS

BARCODES

AS MUSEUMS BECOME more reliant on technology and integrated collection management systems (CMS), the idea of barcoding the objects in a collection has become increasingly attractive and practical. Barcodes are essentially a form of data that can be scanned and read by a machine. Most often, the data is represented by a set of parallel lines and spaces of different widths. Each line correlates with a letter, number, or symbol that when scanned by a device is translated into recognizable data.

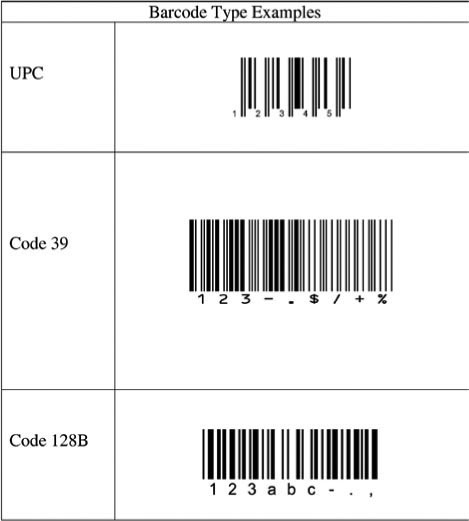

There are multiple barcode fonts available, and several suitable for barcoding collection objects are included in this chapter. Each font has a unique (and proprietary) association between characters and lines. When choosing a barcode font, a museum must consider the type of data being encoded to ensure that each character has a correlating line in the barcode (FIGURE 5G.1). The most common font is Universal Product Code (UPC), which consists only of numbers and can be found in most retail establishments. Code 39 includes numbers 0 to 9, letters A to Z, and a set of six common symbols. Code 128, which has three subsets (A, B, C), includes numbers 0 to 9, letters A to Z in both upper- and lowercases, and most common symbols. Each of the three subsets include a slightly different combination of these features, with Code 128B being the most inclusive.

FIGURE 5G.1 BARCODE TYPE EXAMPLES. CREATED BY AUTHOR.

Considerations for Use

Integrating barcodes with a CMS is useful for a variety of reasons. It can save time previously spent on entering data manually and increase efficiency by accomplishing more data entry in a shorter period of time. A barcode system can increase accuracy because using a scanner minimizes the human error inevitable in manual entry. Barcodes may improve tracking of collection objects and can create a recordable chain of custody. Another benefit is that many collection database systems allow for the integration of barcodes, creating an additional layer of information and object history.

Barcodes are particularly useful for institutions considering a collection move or for those with multiple campuses. They are an excellent resource for large collections or museums with extensive storage facilities. They can be used for temporary projects or as a permanent labeling system for cataloging collections, labeling storage spaces, and tracking collection records. The flexibility, relative simplicity, and reasonable cost of implementing a barcode system makes it a viable option for institutions of all types and sizes.

The practicality of introducing a barcode system is unique to each institution. The most important consideration is whether the implementation of barcodes will save time and create a more efficient system. If the effort and cost to integrate for a short-term project are extensive, but there is no long-term benefit, then barcodes might not be the best option. However, if creating a barcode system will add a needed layer of information or benefit future collections projects, the expense and effort might be worth it, even for a smaller undertaking or collection. The cost of barcoding, both monetarily and in terms of labor and training, should be considered carefully. Many barcode systems have yearly subscription or maintenance fees, and fonts must be purchased. These factors may outweigh the long-term benefits to an institution and should be carefully considered within the scope of collection management strategy and departmental sustainability.

Institutions should investigate whether their current CMS has the capacity to integrate a barcode system. This could be as simple as designating an unused field in a collections management database for barcodes or as complex as pulling data from a CMS into software to generate custom barcodes. In most cases, creating a separate system specifically for barcodes is not cost-effective in the long term, though some museums have found this approach satisfactory for short-term or one-time projects, such as a collection move.

Considering the implementation of a barcode system inevitably leads to the assessment of a collection’s data. The prospect of a data build-out can be daunting because it often underscores existing collection problems or areas in need of work. However, perfect data and a complete inventory are not prerequisites for barcoding. Depending on the system chosen and the database fields used, relevant data groups might need to be standardized or streamlined. If there is a plan to assign barcodes to locations, facilities, or other things not strictly within the collection, then the build-out might be more extensive. It is possible to prioritize and to focus only on data useful to the new barcode system.

Implementation

The first step in implementing a barcode system is choosing which set of characters or data will make up the barcode number itself. A barcode number must be a unique identifier associated with a specific ob ject and its record. This can be either a completely new set of characters, assigned specifically for bar-coding purposes, or an existing field of data, such as an accession number or catalog number. Institutions can purchase premade barcodes or software that generates random barcode numbers. Premade barcodes can be assigned to individual objects in the collection, usually by adding the barcode number to a previously unused field in the database, or as a second identification number.

Alternatively, there are several types of software that pull data fields from databases, which can be formatted to create custom barcodes. Most collection databases automatically assign a unique identifier key to each record as it is created. This helps the computer distinguish between records, even if the data within them change. The key can often be displayed as a field in the database, and it makes a good candidate for a barcode because it is a unique identifier already associated with an object. Some institutions opt instead to use an accession number or catalog number as the barcode number because that is also a unique identifier already associated with an object and record. This can be especially helpful if a tag is separated from an object, as most barcode interfaces allow for manual entry of numbers. It is important to keep in mind that not all barcode fonts can support all characters. For example, if an institution creates a barcode based on its accession number system that include numbers or symbols, then Code 39 or Code 128A/B must be used.

Once produced, barcodes can be printed on most materials including archival paper, polyethylene tags, and acid-free labels. Archival laser print labels are easy to find but are more suitable for outer packaging because the printer ink can smear or transfer to other surfaces. A popular choice for many museums is a thermal transfer printer, which uses heat to melt carbon particle toner onto a label substrate. Thermal transfer printed barcodes last longer, do not smear, and can be printed on materials other than paper. Several archival companies sell acid- and lignin-free adhesive labels for use in thermal transfer printers. Something to consider when printing barcodes is that certain materials allow for a slight bleeding of ink. If the barcode font is too small, this bleed may render the barcode unreadable by the scanner. Testing new brands or types of paper and labels before printing large batches will help avoid costly mistakes. Another common issue is having too large a font, which can result in a barcode being cut off midway or wrapped to another line. Barcodes will not scan unless the complete code is on one continuous line, though most will still scan if the label is upside down or sideways.

Printed barcodes are read by scanners, which come in a variety of types. The most practical type for collections management are handheld scanners, which are small, portable, allow for greater flexibility, and minimize the need to handle objects. Handheld scanners can be individual components, part of pre-made barcode sets, or attachments to devices such as tablets or smartphones. Scanner attachments can be particularly useful if an institution’s CMS has an application or mobile component, or if the use of mobile devices has already been integrated into collections management practice.

Barcodes should never replace physically marking an object with its accession number or catalog number. Although it is possible to affix barcodes directly to objects using conservation grade materials, it is complicated, time-consuming, and not always successful. A far better option is to have barcodes closely associated with an object. Barcodes can be affixed to an artifact tag attached to the object, printed on a card next to the object, attached to an object container, on an adjacent scan sheet, or storage mat, etc. There is always the risk of a barcode being lost or disassociated from its object. This is the main reason that all objects should retain a physical number. However, having additional information on a barcode label also lessens this risk. Many institutions choose to have an object’s name, maker, accession number, and even its home location on the same label as the barcode. It is important to remember that if a barcode number is changed in the database or system, the physical label must be reprinted or it will not scan.

RFID TAGGING

Radio frequency identification (RFID) is another technological tool used to augment CMS. RFID uses radio waves to transmit and read data, sending it back to a central system that records any changes. There are two main types of RFID tags—battery-powered (also known as active) and passive. Active RFID systems use tags that contain a battery and are mainly found in the form of either a beacon or a transponder. Passive RFID tags do not contain their own power source but instead use electromagnetic energy emitted by a scanner to send data. An RFID tag is essentially made up of a microchip and antenna; an active tag also contains a circuit board and battery. The tags usually contain a conductive material such as copper, as well as silicone and a plastic housing. Most are quite small, though active tags tend to be larger to compensate for the extra components. The signals that RFID tags emit are processed through readers, which decipher the information and send it back to a computer. The readers may be handheld or stationary, and in museums, they are often located near points of entry.

Considerations for Use and Implementation

For most collection management, an active RFID system is preferable because active tags continuously emit data, creating an up-to-date, live stream of information, and have a longer range than passive RFID tags. Those in the form of beacons constantly emit signals to the reader, while the transponder type emits a signal when in proximity to a reader. It is important to note that most batteries for active RFID tags have a three- to five-year life span, and as of 2018, replacement batteries were not available on the market. Once an active RFID tag has run out of battery, the whole piece must be replaced.

Passive RFID tags can be useful for institutions interested in tracking objects within smaller ranges, such as a gallery or storage area. They have the advantage of a longer life span and are available in a variety of tag materials and sizes, some of which are quite inexpensive. Unlike active tags, passive RFID tags can be inserted into live animals and plants, making them ideal for tracking living collections.

An RFID tag can store much more information than a barcode, and RFID tags have the ability to track changes in movement, temperature, humidity, and light levels. They can be programmed to send alarms and interact with complex security systems. Like barcodes, RFID tags have unique identifiers that connect directly to an individual record and object. Although this allows for a specific tracking of one object, most RFID systems are separate from existing collections databases. This means any identifying information must be duplicated, and newly generated information integrated into an existing system. However, RFID tags have many benefits, including the ability to be read without a direct line of sight. Most scanners can read an RFID tag through a wooden crate or packing material, and several tags can be scanned at once. This can be beneficial because objects do not have to be handled frequently or unpacked to be scanned.

At this time, the cost to implement a complete RFID tagging system is prohibitive for most museums. Unlike barcodes, it is nearly impossible to implement a RFID system without the help of an outside company, though all offer customized products. As a result, some institutions have chosen to set up systems on a small scale or in stages. Tagging select objects only and setting readers up in only a few galleries can be a cost-effective way to determine whether or not RFID tagging is a viable option. It can be useful if lenders have specific requirements or if an institution has a concentration of valuable objects.

There is some debate regarding whether RFID can compete with signals from other systems, and whether the beacons and transponders are secure from outside readers. If many tags are present in a small area, it is possible to have tag collision, in which the reader picks up multiple RFID tag signals at the same time. This can be resolved through programming, in which the tags submit signals at different intervals. The problem of reader interference, in which multiple readers either interfere with each other’s signals or try to read the same RFID tag at once, can be solved in a similar way. These concerns are specific to an institution’s setup and the various companies providing RFID tagging and can often be rectified with trial and error. Institutions with metal walls or liquid specimens may also have difficulties with RFID tags reading properly and should verify that their chosen RFID company has tags specifically designed to combat this. It should be noted that RFID tags do not differentiate between their intended scanner and any other scanner. As a precaution, sensitive data, such as valuations, should not be included in a tag’s data. It would also be wise to physically remove RFID tags containing identifying data from any collection objects traveling beyond the institution’s boundaries and scanners. •

REFERENCES

Peak-Ryzex. “Barcode comparison chart.” Available at: https://www.peak-ryzex.com/articles/different-types-of-barcodes (accessed July 22, 2019).

IDAutomation. “Barcoding for beginners and barcode FAQ.” Barcodefaq.com. Available at: https://www.barcodefaq.com/barcoding-for-beginners/ (accessed July 22, 2019).

RFID Journal. “Get started.” Available at: https://www.rfidjournal.com/get-started (accessed July 22, 2019).