Chapter 4

The rise of the modern welfare state

Let us continue our exploration of the evolution of the public sector and the rise of the modern welfare state. The historical backdrop for our discussion begins with the devastating depression that swept across the globe in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Leaders in the industrialized countries watched helplessly as the value of their country’s assets seemed to evaporate almost overnight. Meanwhile, national industries collapsed and millions of citizens found themselves unemployed and destitute. As we shall see, these terrible events would compel policymakers in Western democracies to develop new administrative systems and governing approaches.

Believed to have originated in the United States with the stock market crash of October 1929, the Great Depression quickly became the most pervasive economic crisis of the 20th century. Consumer spending and investment plummeted, causing steep declines in industrial output. As economic conditions worsened, countless workers were laid off. A massive deflation in the value of liquid assets caused capital markets to dry up. Befuddled governments hastily erected a series of protectionist policies in an attempt to shield their domestic markets from further international contagion. These measures mainly took the form of beggar-thy-neighbour policies such as tariffs on imports and currency devaluations. The adoption of these stop-gap remedies seemed to make the situation even worse. By the mid-1930s the world economy had plunged into a deep economic depression. The absence of any overarching administrative apparatus or coherent policy strategy resulted in massive gaps in the manner in which national relief provisions were administered among the people in the various countries that were affected. As growing numbers of citizens fell into further distress, Western governments faced intense political pressure to respond with drastic and permanent solutions.

While the precise causes of the global depression remained debatable, the economic ideas espoused by English economist John Maynard Keynes received wide attention. Keynes asserted that an economy moves in cycles, in very specific ways. He believed that aggregate output, and consequently employment, was a function of aggregate demand. He attributed rises in unemployment, therefore, to a shortage of private capital investment and spending in the economy. Keynes attributed this phenomenon to short-sighted privateers, whose investment decisions were often guided by irrational expectations and fears about future profitability. Negative expectations, he asserted, lead to declines in investment spending, thus bringing declines in demand and output, which cause unemployment to rise.

Keynes’s ideas contributed substantially to the emergence of the field known as ‘macroeconomics’. This new field shifted the focus from individual to the aggregate behaviour of economic actors in a country as a whole. Keynesian economists proceeded according to the belief that it was possible for national governments to collect and analyse large sets of economic data and predict crises prior to their occurrence. Armed with this knowledge, governments could then intervene in the economy by using specific sets of fiscal policy tools. For example, governments could increase public expenditures during the onset of economic recessions to help fuel growth, and reduce government expenditures when encountering economic booms in order to reduce pressures on inflation. Governments in Western industrialized countries later adopted a comprehensive set of new regulatory systems and policies aimed at preventing future crises.

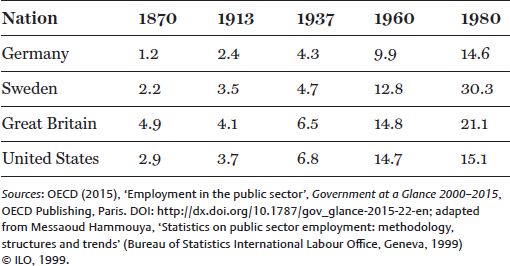

The widespread application of Keynesian ideas by various governments across the industrialized world, ranging from the United States to Europe to Japan and Australia, led many to refer to the period from 1945 to the 1970s as ‘the golden age of managed capitalism’. The American ‘New Deal’ and ‘Great Society’ programmes that were adopted under presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt (FDR) and Lyndon B. Johnson, the programmes of Swedish social democracy, and the welfare programmes introduced by the Labour Party in Britain from 1945 reflected a historic political consensus that was shared across Western democracies (Table 1). This period was characterized by the development of exchange rate regimes to promote stable international markets and the expansion of welfare states to protect labour and the working poor. Let us look at some of the conditions that influenced the rise of modern welfare states in specific countries.

Table 1 Year of introduction of various social services in selected nations

In his book Supercapitalism: The Transformation of Business, Democracy, and Everyday Life, former United States Secretary of Labor, Robert B. Reich, provides a lauding overview of the ‘golden age of managed capitalism’: ‘The economy was based on mass production. Mass production was profitable because a large middle class had enough money to purchase what could be mass produced. The middle class had the money because the profits from mass production were divided among giant corporations and their suppliers, retailers, and employees. The bargaining power of this latter group was enhanced and enforced by government action. Almost a third of the workforce belonged to a union. Economic benefits were also spread across the nation—to farmers, veterans, small towns, and small business—through regulation (of railroads, telephones, utilities, and small business) and subsidies (price supports, highways, federal loans).’

Germany

Germany was one of the first nations to respond to the economic crisis of the 1930s with a series of spending initiatives for new programmes and projects directly aimed at ameliorating the country’s rampant unemployment problem. In the years leading up to the war, however, the face of German welfare policy and the country’s responses to the depression took a dramatic turn. Unemployment insurance, for example, was eliminated and replaced with a broader public works programme.

At the end of the war, Germany was divided into two separate states. West Germany was allied with the Western powers while East Germany became associated with the Eastern European Soviet bloc. These countries had radically different political and economic systems, as well as distinct administrative structures and welfare states. Whereas Eastern Germany adopted the Soviet-inspired command and control—centralized top–down—administrative model, West Germany adopted a more public-centric administrative system like that of most Western-style democracies.

Challenged with having to integrate large numbers of refugees, war veterans, and victims into society in the years immediately following the end of the war, West German leaders were compelled to both reconsider and reconstruct the country’s entire social welfare system. Historic social welfare legislation was introduced as a major part of the nation’s new constitution in 1949 known as ‘The Basic Law’. The Basic Law guaranteed a host of social protections to each citizen through the establishment of a ‘social state’ (Soziale Rechtsstaat). In many respects, the administrative architecture was inspired by the ‘Bismarckian welfare state’ discussed in Chapter 3. The Basic Law mandated that key elements of the national welfare state would apply universally throughout the nation. At the same time, allowances were made within the Law for local governments to apply their own discretion in the way certain social services were administered.

From 1950 to 1969, West Germany experienced soaring economic growth that helped fund the massive expansion of its social welfare system. A highly complex civil service apparatus was responsible for managing and overseeing a vast array of public provisions. While sharing a commitment to democracy and a market economy with countries such as the United States, West Germany gave its government a much more prominent role in the country’s economic affairs. While the market remained the principal mechanism by which most resources would be allocated in German society, the welfare state played a vital role in moderating many of the negative consequences associated with no-holds-barred free market competition. Under a ‘historic compromise’ between the political left and right, Germany’s leaders adopted a ‘social market economy’. Under this arrangement, the state assumed a formal role in facilitating business–labour wage compromises by providing workers with a variety of publicly funded social provisions. A number of social policy measures were achieved through the collective bargaining process. These included, for example, expanding social security provisions to greater numbers of citizens, increasing the amount of public housing available to working families, and adopting provisions for paid vacation time for employees. New legislation also mandated periodic adjustments to public pensions to reflect changes in wages and salaries.

In the 1950s, statutory health insurance was extended to larger groups of citizens, including students, farmers, and those with disabilities. By 1960, the total health expenditure, both public and private, accounted for 4.7 per cent of Germany’s GDP. As health costs skyrocketed in the 1970s, however, the government felt compelled to enact a Health Cost Containment Law. The federal health finance and budget commission known as ‘Concerted Action’ (Konzertierte Aktion) was established to oversee a series of cost containment measures. Since it lacked sufficient political power to impose any serious cost containment measures, its activities proved to be largely symbolic.

Sweden

In the first three decades following the end of the Second World War, Sweden was applauded for sustaining one of the most comprehensive welfare systems in the capitalist world while simultaneously boasting high levels of productivity and economic growth. During the period from 1932 to 1976, a succession of centre-left Social Democratic governments consistently supported the expansion of social provisions. A broad political consensus was forged between those on the country’s political right and left as they came together in support of common public policy agendas. Most notably, a historic compromise was reached between labour and business groups pertaining to areas such as workers’ pensions, labour wages, and corporate taxes. As a result, Swedish workers enjoyed some of the most generous pensions offered anywhere in Europe, while the country’s businesses and stockholders benefited from some of the lowest corporate tax rates in the industrialized world.

As Swedish industry expanded, and the economy flourished in the years following the Second World War, Social Democratic governments continued to support the expansion of the Swedish welfare state. Accordingly, Sweden’s public sector bureaucracy and the administrative system increased in both size and scope. Inevitably, additional pressures were placed on public expenditures. Indeed, public sector spending as a share of GDP continued to grow steadily into the next decade. The 1955 National Insurance Law, for example, extended medical cash benefits (funded by sickness funds, taxes, and government subsidies) to all Swedish citizens. Public education, generous pension benefits, comprehensive healthcare, and social insurance for the unemployed were all extended under Sweden’s state-supported collective bargaining system. These costly social provisions were funded largely through a combination of progressive taxes on workers’ marginal incomes and direct employer contributions.

As the Swedish social welfare system continued to expand throughout the 1960s and 1970s, administrative costs continued to escalate. As a result, a heavy financial burden was placed on the country’s taxpayers, with Swedish citizens becoming among the highest taxed in the capitalist world. Over time, Swedish voters predictably grew disenchanted with the government’s financial management strategies and high taxes. In the general election of 1976, after nearly forty-four years in power, the Social Democrats finally faced defeat. The new conservative-leaning government was resolved to reduce the high costs associated with Sweden’s welfare state, which had been developed under Social Democratic leadership over nearly half a century. However, conservative leaders found it politically untenable to deliver on their promises. The Social Democrats regained power in the election of 1979 and vowed to resume their commitment to the Swedish people. Having returned to power after only three years, Social Democrats enjoyed more than a decade of further uninterrupted rule. Throughout the 1980s, Swedes continued to enjoy high living standards and generous welfare benefits and services. More than 30 per cent of the workforce was employed in the public sector. Perhaps equally compelling is that nearly 60 per cent of the nation’s GDP was spent on welfare provisions. Despite growing political pressures in the mid-1980s for the left-leaning government to rein in government expenditures in the face of increasing public-sector deficits and inflation, the Social Democrats made few adjustments. In fact, they managed to increase the child benefit allowance and extend unemployment benefits. While they were ultimately forced to accept modest cost-containment measures in the base amounts used to calculate certain social benefits, the Swedish welfare state remained largely intact from 1982 to 1991.

The United States

The days immediately following the stock market crash of 1929 proved to be among the darkest in American history. The nation’s financial markets plummeted and millions became unemployed. The election of FDR in 1932 and the introduction of the New Deal reshaped American social welfare policy on a historic scale. In his first hundred days in office, the fiscally minded president introduced a series of modest policies aimed at ameliorating the effects of the crisis. Over the next eight years, however, his administration adopted a more ambitious and aggressive set of government-led initiatives aimed at stabilizing the country’s economy. In an effort to create new jobs and provide new sources of hydroelectric power to boost the economy, FDR worked with Congress to approve funding for the Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA). Established in 1933, this federally owned corporation became the nation’s first regional planning agency. Employing countless engineers, civil planners, and workers, the TVA oversaw the construction and management of massive infrastructural projects, including dams and waterways that were aimed at promoting new development in agricultural areas. At the same time, agricultural subsidies were introduced to help boost commodity prices, which had fallen during the crash of 1929.

With the passage of the National Industrial Recovery Act in 1935, workers were empowered with a new set of collective bargaining rights, which allowed them to organize for higher wages, new benefits, and improved working conditions. Most importantly, however, the Act established a new federally supported Public Works Administration. Unprecedented in scale and scope, this became an important part of FDR’s comprehensive government-led ‘demand management’ programme to revive the economy. Nearly $6 billion was allocated to fund large-scale public works programmes including the construction of new highways, waterways, bridges, hospitals, and educational facilities. Most of the funding was issued through contracts with private firms, in order to support private business growth, create new employment, and bolster the purchasing power of consumers.

During the same period, FDR established the Works Progress Administration (WPA) as part of his grand vision for the country’s economic recovery. Perhaps the best-known of the New Deal programmes, the WPA ultimately provided a variety of employment opportunities to those who would have otherwise been marginalized. Most of the WPA workforce consisted of unskilled labourers who were employed to work on small-scale construction and improvement projects. Under the leadership and supervision of social worker Harry Hopkins, millions of jobs were created, covering a myriad of projects related to public roads, government buildings, parks and recreation, as well as reforestation. Many Americans, however, were relegated to performing menial and unessential jobs and tasks. Additionally, the government commissioned thousands of murals and sculptures which adorned public buildings across the country. Additional funds were earmarked for the theatrical and performing arts. The WPA was later placed under the Federal Works Agency as part of the 1939 Reorganization Act, before being completely phased out in 1943.

The establishment of America’s entitlement system became the crowning achievement of the New Deal. In 1935, FDR signed the Social Security Act, which provided public pension support to millions of retired Americans and also established the country’s first national unemployment insurance scheme. The Social Security Act was designed not only to prevent suffering but also to alleviate it. The programme’s designers sought to improve the lives of those already living in poverty through the introduction of government transfer payments to those in dire need of relief. Much of the funding associated with relief programmes for the poor was provided through the 1935 Aid to Dependent Children Act, which established the programme later known as Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC).

The New Deal policies and programmes fuelled the expansion of the American federal government. It soon became apparent that the executive branch would need to be restructured to successfully implement many of its policies and mandates. A select committee on Administrative Management, popularly known as the Brownlow Committee, was established to create a more tightly structured and coherently managed administrative apparatus. A leading public administration scholar (and former New York City official) by the name of Luther Gulick was invited by FDR to help organize this comprehensive effort. FDR sought Gulick’s counsel when developing strategies for improving the function and operation of America’s public administration system.

In 1937 Gulick and his well-known British colleague, Lyndall Urwick, published ‘Papers on the Science of Administration’ related to Gulick’s work on the Brownlow Committee. Building upon Frederick Taylor’s scientific principles and methods emphasizing ‘the one best way’ approach, as well as Henri Fayol’s functional analysis of administrative management, Gulick and Urwick introduced seven essential functions of management. Presented under the acronym POSDCORB, these essential functions consisted of Planning, Organizing, Staffing, Directing, Coordinating, Reporting, and Budgeting. The characteristics of POSDCORB as discussed by Gulick and Urwick are as follows:

‘Planning, that is working out in broad outline the things that need to be done and the methods for doing them to accomplish the purpose set for the enterprise; Organizing, that is the establishment of the formal structure of authority through which work subdivisions are arranged, defined, and coordinated for the defined objective; Staffing, that is the personnel function of bringing in and training the staff and maintaining favorable conditions of work; Directing, that is the continuous task of making decisions and embodying them in specific and general orders and instructions and serving as the leader of the enterprise; Coordinating, that is the all-important duty of interrelating the various parts of the work; Reporting, that is keeping those to whom the executive is responsible informed as to what is going on, which includes keeping both the executive and subordinates informed through records, research, and inspection; Budgeting, with all that goes with budgeting in the form of planning, accounting and control.’

America’s entrance into the Second World War created millions of employment opportunities. In the years following the war, with its industrial base intact, America led the world in industrial productivity. As the American economy flourished throughout the 1950s, unemployment became less of a political concern. By the 1960s, however, mounting public concerns over America’s unequal distribution of wealth (particularly in parts of the rural South and urban North) inspired the nation’s progressive politicians to return to the issue of poverty alleviation. A number of landmark public sector programmes were adopted under the Democratic presidential administrations of John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, aimed at assisting America’s working and indigent poor. The Johnson administration’s ‘Great Society’ and ‘War on Poverty’ programmes became the centrepieces of this effort. A major entitlement programme, Medicare, was introduced, guaranteeing health coverage to those 65 years of age and older. Medicaid was unveiled soon after, extending basic health coverage to poor American families. Over the next few years, additional federal programmes were introduced, ranging from housing subsidies and school lunch programmes to family planning and women’s support services. The federal government attempted to break the cycle of poverty by extending additional public services to children and their parents. The 1964 Equal Opportunity Act, for example, provided federal financial support for educational and job training programmes, as well as creating new sources of funding for early age educational programmes such as Head Start.

Box 4 Clash of the intellectual titans

In 1952, the American Political Science Review featured an article that would ignite a fiery discussion between Dwight Waldo and Herbert Simon, then two of the leading heavyweights in the field of public administration. The much discussed Waldo–Simon dispute helped crystallize the growing polemic in the field between fact-based, ‘hard science’-oriented approaches, stressing ‘what is the case?’, and normative lines of inquiry emphasizing ‘what is to be done?’ In the APSR article, entitled Development of Theory of Democratic Administration, Waldo emphasized the ‘limitations of science’ by sharply challenging the reigning belief in ‘efficiency as the central concept in our science’. Waldo insisted that ‘efficiency’ should not be treated as a universal axiom, but rather as a contested value that must be explored and debated on philosophical grounds. Indeed, Waldo believed that ‘the established techniques of science are inapplicable to studying’ the things he considered to be the essential elements of public administration—‘thinking’ and ‘valuing human beings’. ‘Questions of value’, Waldo reasoned, ‘were not amenable to scientific treatment.’ Contrastingly, Simon sought to emphasize an empirical, science-based approach to both administrative analysis and decision-making. In so doing, he asserted that logical-positivist-driven administrative ‘science’ should take precedence over value-based approaches. Through his writings on Administrative Behavior, Simon would distinguish himself as an organizational theorist as opposed to a pure public administration scholar. Indeed, he would later be heralded as one of the leading figures of modern (scientific-based) organizational theory both within the field of public administration and beyond.

During the late 1960s and early 1970s, the costs associated with many of these social programmes began outpacing existing financial means. The government ran large deficits, and it increased taxes. The conservative leadership of President Richard Nixon attacked Johnson’s War on Poverty as a source of uncontrollable government spending. Moreover, conservative economists such as Milton Friedman and Herbert Stein convinced the Nixon administration that many of the social programmes adopted during the Johnson era helped support a culture of welfare dependency.

The 1970s proved to be a tumultuous time in American history. During this period, America faced rising unemployment, high inflation, and declining economic productivity. Attempts to bolster economic output through increased public spending on public programmes (consistent with Keynesian demand-management strategies) only seemed to make things worse. As a result, welfare expenditures were viewed as a luxury that the government and the middle class could no longer afford to support.

Britain

The founding principles underpinning the modern British welfare state were outlined in The Beveridge Report released in 1942. Officially known as the Social Insurance and Allied Services Report, it would serve as a general ‘main blue print’of the 1945–51 Labour government’s historic welfare state initiative. It has been suggested that the economic details contained within this historic document were designed in consultation with John Maynard Keynes. This helped boost the document’s credibility in the eyes of influential politicians in parliament. Moreover, the report cemented the British government’s guarantee of a ‘national minimum standard’ of economic security to its individual citizens. While insisting that basic economic security was a political right conferred by citizenship, Lord Beveridge simultaneously expressed concerns over the potential for free rider abuse and the propensity for creating a culture of ‘welfare dependency’. He insisted, therefore, that reciprocal responsibilities be placed on citizens to provide for themselves whenever possible.

Beveridge believed that government not only had the responsibility, but also the ability, to eliminate poverty by providing basic levels of public support to those whose livelihood and earning power was disrupted by structural economic changes and crises. Toward those ends, The Beveridge Report addressed five ‘giant evils’ that he claimed ‘no democracy can afford for its citizens’ in modern society: ‘want, disease, ignorance, squalor, and idleness’. Beveridge argued that these five ills represented a threat to the overall well-being of British society. He insisted that they must be eradicated in order for democratic society to continue to thrive. Beveridge asserted, however, that government needed to adopt the proper means for addressing these social ills in a manner that would not obstruct or stifle personal initiative—nor encourage welfare dependency. Many of Beveridge’s ideas (though not all) helped shape the values and goals underlying the modern British welfare state. While some claim that Beveridge’s direct involvement in most programmatic details was rather limited, the influence of his core principles in guiding the direction of policymakers is difficult to dispute.

In the years following the Second World War, the government adopted a universal social insurance scheme covering all British citizens. Under its comprehensive framework, workers made individual contributions from their weekly paychecks in exchange for a wide range of social provisions. These included universal health and medical coverage, unemployment insurance, senior pensions, maternity support, workplace injury insurance, and burial cost supplements. Of the five evils named in the report only the condition of ‘want’ was addressed directly. That said, the report helped lay the foundation for the passage of subsequent legislation covering the remaining evils of ‘disease, ignorance, squalor, and idleness’. Moreover, the report extended the political definition of ‘liberty’ from ‘freedom to speak, write, and vote’ to ‘freedom from want, disease, ignorance, squalor, and idleness’. Perhaps most importantly, The Beveridge Report directed people’s attention towards the importance of adopting a comprehensive welfare system (Box 5).

Box 5 Main legislative measures inspired by The Beveridge Report

In the 1970s the British government confronted a combination of international financial shocks, high inflation, and increasing levels of unemployment. The Labour government initially responded with state-led demand-management strategies, which ultimately proved ineffective. In 1976, Britain’s economy deteriorated to the point where an International Monetary Fund (IMF) bailout was required to keep the country’s currency from completely collapsing. In the months that followed, public officials and citizens alike began raising serious questions about the affordability of maintaining the current welfare state and, more generally, about the proper role and function of government in the economy. When Margaret Thatcher assumed power in 1979, she noted that in nearly 70 per cent of British households, at least one family member received some form of cash welfare benefit. Determined to roll back state expenditures for social welfare spending, Thatcher’s Conservative government waged a concerted assault on the country’s public sector. We will examine this more closely in Chapter 5.

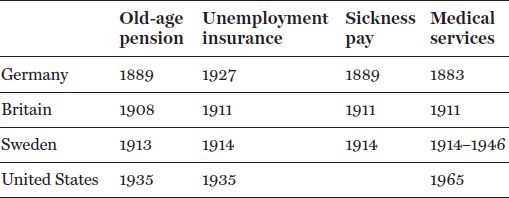

The administrative systems that developed in the late 1800s were inadequate to address many of the complex political and public problems of the industrialized world. The evolution of the modern welfare state reflects the dynamic nature of contemporary society. As societies have become more democratic, citizens have placed increasing demands on government to provide more public services (Table 2). In order to meet the growing demands and expectations of an increasingly complex society, government bureaucracies and public administration systems have been compelled to expand. In the 1980s, conservative-leaning political movements in both right-of-centre and left-of-centre political parties began mobilizing against ‘big government’ and its twin redistributive engines—high taxes and large deficits.

Table 2 Government employment, 1870–1980 (as percentage of total employment in selected nations)