Platonic Ethics and Politics in Themistius andJulian

After he rose to the position of Emperor in 362 CE, Julian did not include his former teacher,388 Themistius, in his strategy for political reform, particularly as it was informed by religious principles, despite the fact that Themistius was one of the leading pagan orators and philosophers of the second half of the fourth century CE. Although Julian filled several offices with pagan officials who were philosophically educated, he seemingly overlooked Themistius.389 Then again, Themistius didn’t fare for the worse either: as Constantius II’s former panegyrist, he was appointed in 355 to the senate of Constantinople,390 was its chairman from 357, and from 357 or 358 until the end of 359 was even proconsul of Constantinople,391 a position he retained under Julian.

Several reasons account for the distance between the former student and his teacher. It may be very important that Themistius, despite his lifelong avowal of paganism, advocated for tolerance392 of Christianity whereas Julian connected the restoration of the old Hellenic cult with increasing restrictions on Christianity.393 Beyond that, scholarship has continually emphasized differences in their political theory.394 What hasn’t been considered however, is that these differences refer back to a difference in their interpretations of Plato. More precisely, that Themistius’ political theory is based on the paradigm of Republic with a few Hellenistic elements (the king is a philosopher, he is god-like, and his main virtue is ϕιλανθρωπία), whereas Julian used the Laws with elements from Iamblichus’ philosophy (the king is only a guardian of the godly laws and needs help from gods, demons and philosophers, and his main virtue is piety, or εὐσέβεια).

This thesis will be demonstrated primarily by using Julian’s Letter to Themistius, supplemented with citations from other works by Themistius and Julian.395

1. Themistius and the philosophers’ kingdom ofPlato’s Republic

Julian’s Letter to Themistius ostensibly precedes a letter from Themistius to Julian (Jul. Or. 6.1.253c1f.)396 after he was appointed as Caesar in Gaul on November 6, 355.397 In it he supposedly wrote that God had appointed him to this position that Heracles and Dionysos had held before him, both philosophers and kings who had purified the earth and sea from increasing wickedness. Julian should “shake aside every thought of leisure and comfort” and, after he had traded the vita contemplativa in for the vita activa (Jul. Ep. 9.262d), accomplish even bigger things than the lawgivers Solon, Pittacus, and Lycurgus (253c–254a). In the surviving oratories of Themistius,398 Dionysius and Heracles were not mentioned in connection to the Platonic philosopher-kings whereas Solon, Pittacus, and Lycurgus, who were counted among the seven wise men, were praised that they didn’t discuss logic, ideas, and astronomy theoretically but rather “enacted laws and taught what must be done and what may not be done, what should be chosen and what should be avoided” and established and stipulated that man as a member of a community is “obligated to care for the laws and the constitution of his native country,” something they had demonstrated practically through their work as emissaries, in the army, or as politicians (Them. Or. 34.3).

Thus, in his letter, Themistius put forth the higher order of the vita activa over the vita contemplativa and a theory of kingship in which he legitimized the contemporary empire against the backdrop of the Platonic philosopher-kings of the Republic. According to Themistius, both the philosopher and the king, the former as theoretician and the latter as practitioner, have the same goal: do something good for humanity; however, the king has the power that the philosopher lacks (Them. Or. 1.9a7-c3). Plato thought that both figures align themselves with same paradigm of the god of the universe, whereby the philosopher has “speech and knowledge” (λόγος καὶ ἐπιστήμη) at his disposal and the king imitates him with “action and deed” (πρᾶγμα καὶ ἔργον) (Or. 2.34b5-c4). Contrary to what Plato suggests, however, philosophers should not be kings, but rather—in the Aristotelian sense—they should stand as advisors by the sides of kings, who should follow their advice (Or. 8.107c2-d3). With reference to the Platonic comparison of the philosopher with a dog, it is the philosopher’s job to differentiate between friend and foe, between the virtuous and the vicious, to curb vice through admonishment and in this way to care for justice and harmony in the state (Virt. 459.24–35).399 This comparison shows the philosopher as a guard, from whose circle, according to Plato the philosopher-king emerges. Therefore, in the end, according to Themistius the philosopher’s charge is the same as the emperor’s, but through official oration. And conversely, the more the ruler follows philosophical advice, the more he becomes a philosopher. Thus Themistius praises almost every emperor explicitly as a philosopher and as the realization of the Platonic philosopher-king (e.g. Constantius, Or. 2.40a4-b2; cf. 34b7–9).400

Consequently, one can say that the Aristotelian dichotomy between advisory philosophy and executive politics is determined by the factual political role of philosopher and king. At the heart of this dichotomy lies the implicit focus on the ideal of the philosopher-kings in Plato’s Republic: In the end, the king should act like a philosopher and the philosopher should think like a king.401 Often his speeches include the call from the Republic (Pl. R. 6.486b10–487a5) for a philosophical soul which he applies to the king: he must be young, congenial, have good powers of comprehension, a good memory and be the friend of the cardinal virtues of wisdom, justice, fortitude, and moderation (Them. Orr. 8.104d7 f.; 17.215b9-c2; 34.16.223.17–21).

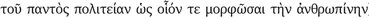

In his philosophy, Themistius argues—following his father and teacher, Eugenius and perhaps referencing Porphyry402—for a harmonization of Plato and Aristotle and sees the goal of philosophy in political philosophy; for Plato the “primary content, end point and high point” of all λóγοι is the “approximation of god as far as it is humanly possible (ὁμοίωσις θεοῦ κατὰ τὸ δυνατὸν ἀνθρώπῳ)” (Or. 2.32d3 – 6 with b9-c3). 403 This is in Middle as well as Neoplatonism the standard formulization of the summum bonum. Plato pursued mathematics, astronomy and metaphysics in order to “bind the human assets with the godly assets and to allow the human πολιτεία to emulate the πολιτεία of the universe to the greatest extent possible (πρὸς τὴν  )” (Or. 34.5.215.12–20). This shows that according to Themistius, the individual’s ὁμοίωσις to god is transferred to politics: The human πολιτεία is the ὁμοίωσις to the cosmic πολιτεία.

)” (Or. 34.5.215.12–20). This shows that according to Themistius, the individual’s ὁμοίωσις to god is transferred to politics: The human πολιτεία is the ὁμοίωσις to the cosmic πολιτεία.

According to Themistius, Aristoteles differentiates himself from Plato through a larger diversity of interests and level of detail, but all of his work refers to human goodness and is dependent upon it (Them. Or. 34.6.215.26–216.3). According to Aristotle, the goal of virtue is not the knowledge (γνῶσις), but rather the practice (πρᾶξις) (Or. 2.31b10-c7, d6–32a4).404 Philosophizing is nothing more than “practicing virtue” (ἐργάζεσθαι ἀρετήν) (31d5–6). Aristotle taught the subordination of ethics (Or. 34.6.216.3–11) and even cosmotheology to politics: The unmoved mover and all the stars would conduct political philosophy in that they “preserve nature as stabile and unscathed for all eternity (ῥυομένους τὴν ὅλην φύσιν ἀκλινῆ καὶ ἀκέραιον δι’ αἰῶνος)” (216.13–16). Thus for Themistius the Aristotelian cosmotheology is the model for human governance. For Themistius both Plato and Aristotle see theology, metaphysics, and general theoretical philosophy not as ends in themselves, but to be conducted for the sake of practical and political philosophy.

In Themistius’ “political theology” the emperor is the “flawless, perfect image of god (ἄγαλμα τοῦ θεοῦ)” in that, like god he is able to do more good than any other humans and imitates god in his domain (Them. Or. 1.9b4-c1). The ruler’s ὁμοίωσις to god consists solely in φιλανθρωπία, the virtue to do good for humanity, since he cannot share the other qualities of god such as eternal life and omnipotent powers (Or. 6.78d7– 79b2). The rule of the emperor should be an image of the cosmic order of god, determined by justice, peace, and goodness (Or. 15.188b5–189a7). In particular, in the stoic sense the emperor expresses the “law animate” (νόμος ἔμψυχος) and functions on earth as the “emanation” (ἀπορροή) of god and his φιλανθρωπία (Or. 5.64b4–8). In particular he mitigates the written law if it leads to undue hardship in individual cases (Or. 1.15b3–8). In contrast, the law-abiding subject desires to “live according to the law” and “emulate the king and pay attention to his behavior” (In Met. 12.20.8f.; 23).

This “political theology” has Dio Chrysostom as a model. In his first oration On Kingship, Chrysostom ascribes the earthly kingship to the rule of Zeus: Both are bound together through the “single statute and the single law” (ὑφ’ ἑνὶ θεσμῷ καὶ νόμῳ) and “partake in the same πολιτεία” (τῆς αὐτῆς μετέχοντας πολιτείας) (Dio, Or. 1.42–45). In his Borysthenitic Discourse, he appeals to Plato and Homer, calling the cosmos the “best kingship (βασιλεία)” of Zeus, which is governed “in accordance to the law with friendship and unity” and is the “model” (παράδειγμα) for earthly kingship (Or. 36.29–32). Even  as a central virtue of the king is predetermined by Dio insofar as the king rules over many people and is loved by them (Or. 1.15; 17–18). According to Themistius, however,

as a central virtue of the king is predetermined by Dio insofar as the king rules over many people and is loved by them (Or. 1.15; 17–18). According to Themistius, however,  is not determined by the number of the king’s subjects, but rather according to his similarity to god. Dion links the stoic theory of κοσμόπολις in which humans are bound to the gods solely through a law of rationality, to the Platonic idea that the summum bonum in ethics and politics is the ὁμοίωσις to god.405 Themistius takes this Platonic-stoic amalgam but expands it with Aristotelian cosmotheology through which the πολιτεία of the gods can also be interpreted.

is not determined by the number of the king’s subjects, but rather according to his similarity to god. Dion links the stoic theory of κοσμόπολις in which humans are bound to the gods solely through a law of rationality, to the Platonic idea that the summum bonum in ethics and politics is the ὁμοίωσις to god.405 Themistius takes this Platonic-stoic amalgam but expands it with Aristotelian cosmotheology through which the πολιτεία of the gods can also be interpreted.

2. Julian and the rule of law of the Platonic Laws

In his Letter to Themistius, Julian responds to his former teacher beginning with his privileging of the vita activa over the vita contemplativa. According to Julian, the philosopher could be “through the education of philosophers, even if it’s only three or four, of greater benefit to many people than several kings together” (Jul. Or. 6.11.266a5-b1). In this way almost all philosophical schools harken back to Socrates whereas during Alexander’s victories, virtue increased neither in any polity nor in any individual (10.264c3-d8).

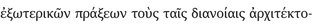

In this sense Julian’s letter corrects Themistius’ interpretation of Aristotle’s Politics 7.3: According to Themistius, Aristotle praises good action (εὐπραγία), specifically the practical life (πρακτικὸς βίος) and the “architects of good deeds” (καλῶν πράξεων ἀρχιτέκτονας), which he ostensibly identified with kings (Arist. Pol. 7.3. 1325b14–16, 21–23). Julian wrote out the apparently abbreviated citation: “We most correctly use the word ‘act’ of those who are the architects of public affairs

by virtue of their intelligence” (

),be it the lawgivers, the political philosophers and “all those who act according to intellect and reason (

),be it the lawgivers, the political philosophers and “all those who act according to intellect and reason ( )” and not “those who do the work themselves and those who transact the business of politics” (

)” and not “those who do the work themselves and those who transact the business of politics” ( ) (Jul. Or. 6.10.263d1–264a1).

) (Jul. Or. 6.10.263d1–264a1).

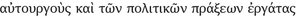

With a detailed citation from Plato’s Laws406 about Cronus’ regime and its interpretation, Julian sums up his Neoplatonic image of kingship (Plat. Lg. 713c5–714a8; Jul. Or. 6.5.258a4-d7): Since Cronus recognized that no human can master human affairs without hubris and injustice, he established out of philanthropy that no man should be kings and rulers over people, but rather introduced a “better, god-like race, the demons.” According to Plato, this myth means that there is no relief from evil for any city “if a mortal rules instead of a god,” therefore one must “imitate (μιμεῖσθαι) with all means the way of life that existed at the time of Cronus; and insofar as immortality is in us ( ) one ought to be guided by it in our management of public and private affairs, of our houses and cities, calling the distribution of intellect (νοῦ διανομήν) law (νόμον).”

) one ought to be guided by it in our management of public and private affairs, of our houses and cities, calling the distribution of intellect (νοῦ διανομήν) law (νόμον).”

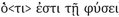

Julian interprets this myth with an eye to the king’s nature and virtue: “Even when one is by nature (τῇ φύσει) human, he must in his conduct (τῇ προαιρέσει) be godly and demonic by banning everything mortal and brutish from his soul, except what must remain to safeguard the needs of the body” (Jul. Or. 6.5.259a–b2). Here Julian employs Neoplatonic doctrines, specifically the doctrine of two human natures, the doctrine of scala virtutum and of summum bonum: man is, as he shows in his Oration to Helios, a “dual conflicted nature in which soul and body are compounded into one, the former godly, the latter dark and gloomy” (Jul. Or. 11.20.142d5–7).407 Through his conduct or moral decision, the προαίρεσις, a human can turn toward the rational “godly” part of his soul and come to a ὁμοίωσις to god, if he progresses step by step on the scale of virtues to the highest level of virtue that it is possible for him to achieve. According to Porphyry who was the first to systematize Plotinus’ scale of virtues, the human who purifies himself in the sense of cathartic virtue, is one who is a “demonic human or also a good demon” and the purified human, who occupies the theoretical virtues and whose soul is active in and to the intellect is a “god” (Porph. Sent. 32.89–93).408

According to Julian, Aristotle agrees with this interpretation of the Laws when he argues against the kingship as the best form of government, stating that a king can also have bad progeny and in this case would require “a virtue greater than belongs to human nature (μείζονος ἀρετῆς ἢ κατ’ ἀνθρωπίνην φύσιν)” to not bequeath his kingdom on his children (Jul. Or. 6.7.260d4–261a4 with Arist. Pol. 3.15.1286b22–27). A kingship requires “more than a man is capable of,” namely a “demonic nature” (Jul. Or. 6.7.260c5-d4). Instead of that, one may only cede the kingdom to the law— what Aristotle calls “intellect without ambition (ἄνευ ὀρέξεως νοῦς)”—and not to any man, because even in the best of men the intellect is bound up with appetite (θυμός) and desire (ἐπιθυμία), “the most ferocious animals” (Jul. Or. 6.7.261d2–6 with 261b5-c2 and Arist. Pol. 3.16.1287a28–32).

According to Julian, laws are only just if the lawgiver has purified his intellect and soul (τὸν νοῦν καθαρθεὶς καὶ τὴν ψυχήν) and if he theoretically recognizes the “nature of the state (τὴν τῆς πολιτείας φύσιν)” and the “naturally just (τὸ δίκαιον  )” and unjust (Jul. Or. 6.8.262a1-b3). The perfection of the entire political system derives from the personal perfection of the lawgiver and his theoretical knowledge of ideas. He is in the position to “carry the knowledge of ideas concerning the correctly composed state and justice from there to here (ἐκεῖθεν ἐνταῦθα μεταφέρων)” and to determine common laws for all citizens independent of whether they are friend, foe, neighbor or relative (262b3 – 6).

)” and unjust (Jul. Or. 6.8.262a1-b3). The perfection of the entire political system derives from the personal perfection of the lawgiver and his theoretical knowledge of ideas. He is in the position to “carry the knowledge of ideas concerning the correctly composed state and justice from there to here (ἐκεῖθεν ἐνταῦθα μεταφέρων)” and to determine common laws for all citizens independent of whether they are friend, foe, neighbor or relative (262b3 – 6).

It is likely that this idea comes from Iamblichus.409 In a letter to Agrippa, he called law the “king of all” and the “good for all in common (κοινὸν ἀγαθόν)” without which there could be no goodness. The law’s essence dictates what is good and forbids what is bad, extends to all kinds of virtue and pervades the entire public administration and individual way of life (Stob. 4.77.223.14–24).410 The “official who should oversee the laws (τὸν προϊστάμενον τῶν νόμων ἄρχοντα),” the “preserver and guardian of the laws (σωτῆρα καὶ φύλακα τῶν νόμων)” must be “completely purified regarding the highest correctness of the laws (εἰλικρινῶς ἀποκεκαθαρμένον εἶναι πρὸς αὐτὴν τὴν ἄκραν τῶν νόμων ὀρθότητα)” and as far as it’s humanly possible, must be “immune from corruption (ἀδιάφθορον),” must not allow himself to be misled by ignorance, deceptions of frauds, and may not give in to violent influence or unjust excuse (223.24–224.7).

It is likely that by the “preservers and guardians of the laws” Iamblichus was referring to the  of the Laws upon whom the oversight of the laws and also a partial legislative process is incumbent if existing laws need to be expanded or revised.411 The “complete purity regarding the highest correctness of the laws” probably refers to the pure intellectual understanding of intelligible good as it is manifested in the given laws. Proclus, referring to Plato’s explanation of νόμος as νοῦ διανομή, describes the legislative process as becoming a “particular intellect (νοῦς τίς ἐστι μερικός)” (Procl. In R. 1.238.22–25): the intellect through which the transcendental godly intellect is communicated to souls and through which they become “noeric” and perfect (Procl. In Alc. 65.20f.; In Tim. 2.313.3f.). One could thus say that for the Neoplatonists the laws are the transformation of the intelligible idea of good and just in rationally comprehensible, propositional commandments and prohibitions and that in this way the godly intellect actualizes itself in the intellect of humans and the human community.

of the Laws upon whom the oversight of the laws and also a partial legislative process is incumbent if existing laws need to be expanded or revised.411 The “complete purity regarding the highest correctness of the laws” probably refers to the pure intellectual understanding of intelligible good as it is manifested in the given laws. Proclus, referring to Plato’s explanation of νόμος as νοῦ διανομή, describes the legislative process as becoming a “particular intellect (νοῦς τίς ἐστι μερικός)” (Procl. In R. 1.238.22–25): the intellect through which the transcendental godly intellect is communicated to souls and through which they become “noeric” and perfect (Procl. In Alc. 65.20f.; In Tim. 2.313.3f.). One could thus say that for the Neoplatonists the laws are the transformation of the intelligible idea of good and just in rationally comprehensible, propositional commandments and prohibitions and that in this way the godly intellect actualizes itself in the intellect of humans and the human community.

This also explains the fundamental difference between Julian and Themistius even though they both call on Plato: Unlike Themistius, Julian does not determine the king to be the “law animate (νόμος ἔμψυχος)” that stands above all other laws, corrects existing laws, and decrees new ones. Rather, in the sense of Plato’s Laws, he subordinates the king completely to the law, before which all are equal412 with his legitimacy coming from his rationality.413 While Themistius speaks factually to the ideal of the philosopher-king from the Republic, Julian pursues the Laws’ second-best constitution414 of the rule of law as the model for his politics. Julian thus rejects the role of philosopher-king that Themistius ascribes to him and places the law as the ideal ruler in the center of politics. He asks the philosophers and, through them, the gods for help, willingly subordinating himself to the philosophers as advisers who by virtue of their “godly, demonic nature” are more suited to be νομοφύλακες, or guardians of the godly laws.

In addition, there is a certain tension between the fact that Julian, due in particular to his factual positional power as Caesar and later as the sole Emperor, is

“ranked above” the philosophers (Jul. 6.267d1) and that in a certain sense, he is the only  (6.7.261a6) since he, in contrast to the philosophers can politically accomplish the actual observation of the laws. Precisely because of the ruler’s voluntary subordination to the law and his claim of originating from the godly intellect any particular decision achieves a similar validity as that of the Hellenistic god-king since this is not contingent on his birth, but rather is based on the necessity of the godly law and on the advice of philosophers, who interpret the godly law according to their deeper understanding of ideas. In this sense he is the only politically legitimate

(6.7.261a6) since he, in contrast to the philosophers can politically accomplish the actual observation of the laws. Precisely because of the ruler’s voluntary subordination to the law and his claim of originating from the godly intellect any particular decision achieves a similar validity as that of the Hellenistic god-king since this is not contingent on his birth, but rather is based on the necessity of the godly law and on the advice of philosophers, who interpret the godly law according to their deeper understanding of ideas. In this sense he is the only politically legitimate  since he preserves the godly law and its reason according to the interpretation of proven experts.

since he preserves the godly law and its reason according to the interpretation of proven experts.

3. Julian and the Platonic “laws” of piety andmoderation

Not only the constitutional framework of Julian’s kingship, but also laws he enacted are based on the Laws. It’s often pointed out that the most striking characteristic of Julian’s politics is his religious policy. O’Meara415 has already pointed to some of the similarities between Julian’s religious policy and Plato’s Laws: old religious traditions take precedence over new ones; local gods are accepted and integrated into the religious system; piety has a political function and is publicly promoted.

Julian’s second Panegyric in Honour of the Emperor Constantius (Or. 3), presumably given in 359 when he is Caesar, documents this eminent meaning of piety quite well.416 Here, piety (εὐσέβεια) is the emperor’s most important virtue: It is a “sprout of justice (τῆς δικαιοσύνης ἔκγονος)” which belongs to the “more godly form of the soul” therefore one may “not depart from the lawful worship of the gods (ἐννόμου θεραπείας)” nor condemn the worship of “something higher (κρεῖττον)” (Jul. 16.70d2–6).417 Even a commander or king must “serve god like a priest or a prophet with due respect” and not see such a service as unworthy of his person (Jul. 14.68b7-c2). Thus according to Julian, the emperor should not only formally occupy the traditional office of pontifex maximus but should be a practicing priest himself through his personal conduct. Julian did this later as Emperor, which brought him the criticism and derision of his contemporaries (Amm. Marc. 22.14.3).

The “Mirror of Princes” of the second Panegyric in Honour of Constantius (Jul. 3.23–33.78b–93d) contains a catalog of virtues which refers back to Dio (Dio Or. 1.15–32). Like Dio, Julian divides the catalog between duties to the gods (ἐπιμέλεια θεῶν) and duties to men (ἐπιμέλεια ἀνθρώπων). In a more narrow sense this means  such as proper conduct in war toward the city and rural

populations and toward officials and soldiers. The first virtue is piety which means not only piety toward the gods but also piety toward one’s parents whether they are living or already deceased, good will toward one’s brothers, holy awe (αἰδώς) of the gods of kinship and clemency (πρᾳότης) toward foreigners and suppliants (Jul. 28.86a3 – 6).

such as proper conduct in war toward the city and rural

populations and toward officials and soldiers. The first virtue is piety which means not only piety toward the gods but also piety toward one’s parents whether they are living or already deceased, good will toward one’s brothers, holy awe (αἰδώς) of the gods of kinship and clemency (πρᾳότης) toward foreigners and suppliants (Jul. 28.86a3 – 6).

This expanded definition of piety harkens back to a law from Plato’s Laws. The preface to the legislative part in the Laws describes the task of σώφρων, which, through ὁμοίωσις θεῷ (“being like god”) accomplishes εὐδαιμονία. Being σώφρων requires the correct honoring of the gods (θεραπεία θεῶν) in sacrifices and prayers (Lg. 4.716d4-e1)—in a descending order from the Olympic gods and patron gods of cities, to subterraneous gods, demons and heroes down to the family gods (717a6-b5) —, then “honoring parents who are still alive” since everything that one has in terms of property, body and soul one has received from them and owes them the oldest and greatest debt, and then the honoring of deceased parents (717d6–718a6). Finally, there is the duty toward offspring, relatives, friends, fellow citizens and the “services to foreigners that the gods demand” (718a7f.; 5.729b–730a). Julian replaces the pious respect of children with the good will amongst brothers, perhaps because neither he nor Constantius had children and their different relationships to their brothers (Constantius to Constans and Julian to Gallus) could be a good starting point for a critique of “impious” emperors. In the end the emphasis is on care for foreigners, the so-called φιλοξενία, a counterpoint to the relief for the poor which Christian rulers traditionally practiced.418

In his polemical satire Misopogon, in which Emperor Julian engages with the Antiochenes’ rejection of his religious restoration policies and the politically controlled economic activities in Antioch in the winter of 362/363,419 Julian justifies his political activities with two laws from Plato’s Laws: “The great, perfect man in the polis” who has earned the “virtue’s victory prize” is the one who not only doesn’t commit an injustice himself, but rather who also deters others from committing an injustice by reporting their injustices to the rulers and officials (ἄρχοντες) and, together with them, seeks punishment, or he’s the one who not only possesses moderation, prudence and all other virtues, but who can also “share (μεταδιδόναι)” them to others (Jul. 25.353d5–354a6; Plat. Lg. 5.730d2-e3). The latter is the teacher of virtue, the former is a kind of “informer” whose actions are morally praiseworthy because he moves to punish the wrongdoer and morally improve him,420 or averts further injustice and harm from the community.421

According to the second law from the Laws, the rulers (ἄρχοντες) and the elders must practice “awe (αἰδώς)” and moderation (σωφροσύνη) “so that the masses who look up (ἀποβλέποντα) to them follow (κοσμῆται)” (Jul. 354b6-c2; see Plat. Lg. 5.729b5-c2). Julian adds to Plato’s named elders the “rulers (ἄρχοντες)” or officials because for him the officials in particular must make their subordinates virtuous through their particular model of virtue. In the Platonic sense, the virtuous individual is the personal model of virtue for those who are not yet virtuous; they have to look to the virtue of the virtuous individual and to imitate him– similar to the way in which particular beautiful things look to the idea of beauty and attain their beauty from there. In a topical manner of speaking “moderation, the σωφροσύνη, is the κόσμος of the soul”, thus its “adornment” or its “organization.” This “organization” refers to the subordination of the non-rational to the rational part of the soul or, as Porphyry stated, “the agreement of the desiring part of the soul in accordance with the deliberation” (Porph. Sent. 32.11 f.). Like the catalog of virtues of the second Panegyric in Honor of Constantius, Julian’s definition of  begins with piety and implies being law-abiding.422 This is because

begins with piety and implies being law-abiding.422 This is because  means “to know that one must be subservient (δουλεύειν) to the gods and the laws” (Jul. Or. 12.9.343a3f.).

means “to know that one must be subservient (δουλεύειν) to the gods and the laws” (Jul. Or. 12.9.343a3f.).

To summarize, the Platonic Laws urge Julian to piety in ways that extend not only to the gods, but also to family, relatives, and all people insofar as they are foreign or in need of protection, and beyond that to the didactic duty of those who are virtuous to educate the less virtuous through punishment, instruction and personal example. The role of the officials as mediators of virtue is stressed so that, according to the cited passage from the Laws, a hierarchy of virtuous individuals results: the “perfect man of the polis” at the top, then the officials, and finally the mass of subjects. This trichotomy has a distant resemblance to the Republic. To imagine the self-subordination of the ruler to the gods, philosophers and the law in Julian’s Letter to Themistius means that the virtue of the “perfect man” at the top of the polis is no higher ranked virtue than that of his officials or subjects. It is merely obedience to the gods, philosophers and laws, something he shares with the officials, and together they have the political authority to lead the subjects to obedience.

4. Conclusion

Julian, unlike Themistius, does not maintain a formal dependence on the Platonic Republic for his image of society which identifies that ideal image with the social and political reality of the actual society in 400 CE. Rather Julian attempts–in alignment with the Neoplatonic reform program—423 to take the “second-best” constitution from the Platonic Laws in order to reform the politics and society of his time. This means a no less ambitious project than the Republic, which is distinguished by the largest possible community sharing all goods (for example the well-known communities of women and children), attitudes and value judgments, and even sentiments.424 Instead of that, in the polis of the Laws both private property and family are allowed. Common laws and education allow a community of many individuals, their attitudes and emotions regarding the common good.

From the point of view of a reform program which is modeled by the Laws, Themistius’ assertion of a nearly realized Republic seems like propaganda and flattery, as Julian’s first reaction to Themistius’ letter shows. He takes Themistius’ comparison of him to Dionysius, Heracles and the ideal of the philosopher-king—with the necessary politeness of the letter—for mere flattery or even lies (Jul. Or. 6.2.254b2f.). At the same time he takes Themistius’ philosophical arguments seriously and attempts to refute them. In the end he asks him, along with all philosophers, for help with his political challenge (Jul. 6.13.266d5–267a2). His stance toward Themistius can be described as ambivalent at best.

Conversely, Themistius may have felt thoroughly misunderstood. Because his theoretical orientation toward the philosophy kingdom of the Republic, which he freely avoids in favor of an Aristotelian dichotomy between advice giving philosophy and advice following politics is nothing more than a conventional topos of his panegyric. At the same time it might have been his strategy to show the emperor his real challenge with the exposition of his political ideal, in order to offer him his advice or even his critique. According to Themistius’ self understanding the accomplishments and challenges of philosophers include advice, critique and education of the people, as well as of his ruler, and the politically active creation of peace in war and harmony among the people (Virt. 44–47.458–462).425 This is apparently a challenge from the emperor, which the philosopher, even though he has no political power, takes on solely through his speeches and his public example.

In this sense Themistius has the same effect as the “great, perfect man in the polis” cited in Julian’s Misopogon. He is not only himself virtuous, but he is also capable of teaching others about virtue even if it is through the conventions of the panegyric and within the confines of his political position. And Themistius fulfills the task of philosophy defined by Julian in his Letter to Themistius and when he asks for Themistius’ help as a philosopher. However, as we’ve seen even if one accepts this partial agreement, Themistius still diverges from Julian in the theory of kingship and above all the role that piety plays for the king. Thus it is not surprising that Julian sought philosophical advice more from Maximus of Ephesus and Priscus who, in the tradition of Iamblichus, taught the connection between theurgy and philosophy and who supported his preference for divination, sacrifices and other ritual practices. With his balanced and tolerant paganism, Themistius hardly came into consideration as an advisor and educator, even if Julian still valued him as a former teacher. For these reasons Julian could hardly entrust him with a higher office, even if he didn’t revoke the one he already had. Despite their partial agreement the distance between the leading panegyric of the second half of the fourth century CE and the last pagan emperor was seemingly mutual.