Jubilee Mill, 1887, Gate Street, Blackburn – front view. The author

The year 1912 was memorable both nationally and locally. In the town of Blackburn a new police station and Sessions House were opened on Northgate, a statue in memory of William Henry Hornby, the Borough’s first mayor, was unveiled by his son in Limbrick and a reconstructed County Court came into use.

It was a time when theatres and music halls which had hitherto been the main sources of entertainment began to suffer as moving pictures and cinemas grew in popularity. The Union Workhouse on Whinney Heights like many other such countrywide institutions of filth, undernourishment and cruelty was in decline from its Dickensian heyday. The National Insurance Act and Old Age Pensions Act together with other government reforms were beginning to bring about the downfall of the workhouse ‘palaces of despair’. However, locally, the biggest news early in the year was surely Blackburn Rovers winning their first Football League Championship, a triumph which eclipsed even their five previous F A Cup successes – the last of them in 1891.

The year also saw, in April, that greatest of all maritime disasters – the sinking of the Titanic. In fact, two men from the town, Jonathan Shepherd and Thomas Teuton, lost their lives along with 1,502 others on the luxury liner when one watertight compartment too many belied its name on the freezing cold night of 14 April 1912.

On a lighter note, it was also a year of record asparagus prices and entertaining news from Osaka, Japan. A busy street near the museum garden was the scene of unprecedented excitement and alarm. From a drainpipe by the pathway a long ominous-looking snout protruded. It was unnoticed at first by passers-by until, suddenly, it commenced to snap viciously at their legs. The unexpected shock caused to unsuspecting Oriental pedestrians can only be imagined. Even in these benighted days of all too frequent assaults and muggings no one remotely expects to be accosted via drainpipes in the street but such was the fate of the unlucky citizens of Osaka that distant spring day.

Jubilee Mill, 1887, Gate Street, Blackburn – front view. The author

Jubilee Mill, Blackburn – side view. The author

The fearsome snout was secured with ropes by the authorities and, in the absence of any other alternative ideas, it was decided a tug-of-war pull on the ropes was the best option. Several desperate heaves later, a large crocodile was finally dragged into view. It transpired that the reptile had escaped from its cage at the museum in September 1910 and thereafter, for eighteen months or more, had been exploring the drainage system of the city. Who would have been a sewage worker in Osaka in those days if they’d known about the maneater lurking beneath the city’s manholes? Locally, on a very much more sombre note, 1912 was also the year of the long-forgotten murder in the mill.

Jubilee Mill in Gate Street off Eanam in Blackburn had been built in 1887. In 1912 it was owned by Messrs John Taylor Ltd and was to be the scene of a horrific murder rather than any celebrations during its twenty-fifth year of existence.

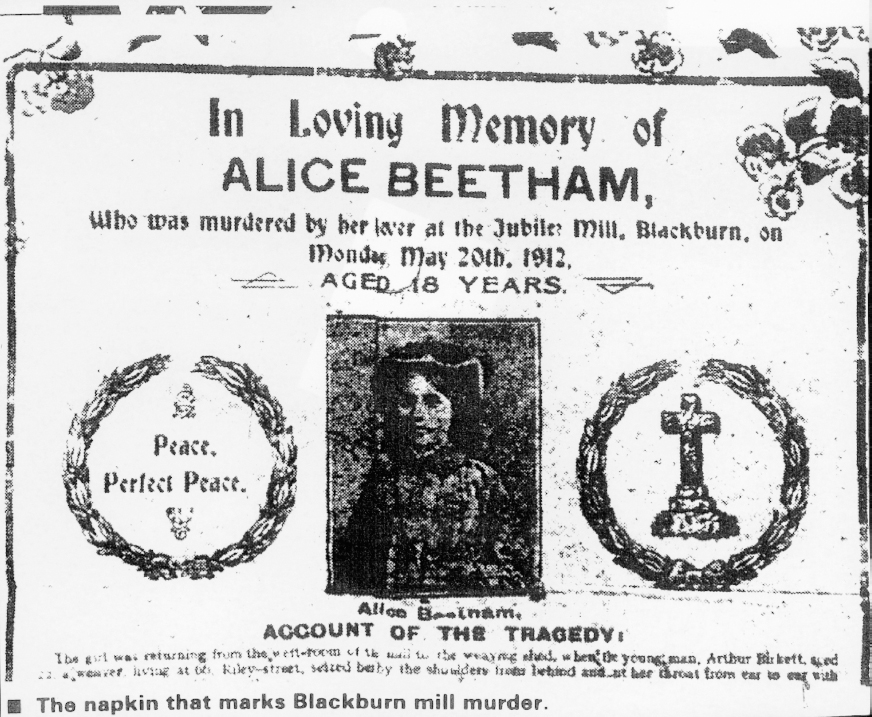

On Monday, 20 May 1912, at 9 am, young pretty Alice Beetham was going about her work as usual in the busy mill. Eighteen years old, of dark complexion and good-looking, Alice had a cheerful disposition and was a favourite with everybody who knew her. She was returning from the weft room when, suddenly, as she came through the weaving shed door, she was seized by a fellow worker she knew well –twenty-two year old Arthur Birkett.

Before Alice realised what was happening Birkett, razor in hand and murder in mind, cut her throat in a single vicious movement. As Alice dropped to the floor, blood gushing from the horrendous wound, Birkett turned the razor on himself opening two wounds in his own neck.

Panic ensued amongst the mill workers at the awful realisation of what had happened in their midst. Susie Tattersall of Coddington Street and Edith Rimmer of Artillery Street got hold of Birkett who had also fallen to the ground. They tried to pull him away from the vicinity of his victim but only succeeded when weaver John Dewhurst arrived to assist them and prevent Birkett from inflicting any further damage on himself.

The mill manager, Mr Smith, rushed to the scene and examined Alice Beetham. She was quite dead and, to his horror, Smith discovered her head was very nearly severed from her body. The strength and ferocity of Birkett’s fatal assault was all too clear to the shocked and shaken man. When he had recovered sufficiently, Smith turned his attention to the perpetrator of the crime nearby. He found that Birkett was bleeding profusely yet, despite the two wounds in his neck, he seemed to have missed the front of his throat. Smith bandaged Birkett’s wounds and immediately sent for the authorities. Later, searching the weft room, he found a razor by the rails on the floor.

An ambulance arrived and Arthur Birkett was taken away promptly to the infirmary. Subsequently, Alice’s body was removed to Copy Nook Police Station. Mr Smith found it impossible to keep the mill working after the morning’s events and eventually shut up shop telling everyone to go home. Truth be told, he had no inclination to carry on working himself after what he’d seen. The terrible recollection of Alice Beetham’s head barely attached to her body was already beginning to haunt him.

Arthur Birkett’s mother was at work ten minutes away at Audley Bridge Mill when she heard of the tragedy at the Jubilee. Totally unable to take in what she’d been told and in a state of shock, she immediately left her work and hurried home as fast as she could. The local press, Beckham-like on the ball, were quickly on her trail.

A Telegraph reporter questioned the distracted, tearful woman (enthusiasm and the prospect of a ‘scoop’ momentarily perhaps getting the better of sympathy and sensitivity) shortly after her arrival home at 54 Riley Street, Blackburn. Attended by several concerned neighbours she said she was at a loss as to how such a thing should come to pass. Her son had said nothing to her though she had noticed that he had been unusually quiet and a little depressed since the previous weekend. ‘Always a good lad at home’, he’d been passionately fond of the young girl he’d killed and they’d been stepping out together since Easter that year. Mrs Birkett made the, perhaps telling, observation that her son had been teetotal during this period of courting.

It transpired that Alice Beetham had come to tea at the Birketts’ home a fortnight before the murder when she and Arthur seemed very happy and fond of each other. As Arthur Birkett, according to his mother, had been out of sorts over the last weekend it was clear something traumatic had occurred recently to upset the course of true love in their relationship. Whatever it was, it was enough for Alice to break off the affair on Thursday, 16 May, little realising her decision was her death warrant and she was to die just four days later.

Alice Beetham, the murdered girl. Northern Daily Telegraph

The day after the murder an inquest was opened at 9.30 am at Copy Nook Police Station, Blackburn, which attracted quite a crowd outside. The main business was the formal evidence of identification. Present were the East Lancashire coroner Mr H J Robinson and Superintendent Hodson of the Blackburn Borough Police. Dixon Grimshaw was the foreman of the jury.

The father of the dead girl, Thomas Edward Beetham, who worked as a driller in a small foundry, gave his evidence. He had had the wretched task of identifying Alice’s body at the police station after the crime and he confirmed it was his daughter. That was quite enough for the coroner who immediately adjourned proceedings till Friday week at 9.30 am in the Town Hall.

While Arthur Birkett’s condition improved in the infirmary queues of folk flocked to the Beethams’ house at 24 Billinge Street, Blackburn, during the next few days following the murder – all requesting to see the body. The situation rapidly became heated and intolerable, so much so that the police had to be called in the evenings after the factories had closed to keep the crowds back. People came from all over the town and the surrounding districts in such numbers that, eventually, Mr and Mrs Beetham stopped admitting everyone save friends and close acquaintances. By 24 May they, like everyone else interested in the case, heard the news that Arthur Birkett was rapidly recovering and ‘quite out of danger’.

The ‘Editor’s Postbag’ of the Northern Daily Telegraph of 24 May contained the following appeal pending Alice’s funeral…

I devoutly hope that when the young innocent creature, the victim of the dreadful tragedy at Blackburn, is borne to her grave on Saturday there will be respectful restraint shown by spectators and that there will be no crushing and following crowds nor any exhibition of undue vulgar curiosity. Let the cemetery, for the time, be left to the relatives and immediate friends to bury their dead in peace. One other hint, don’t let the photographers have to show men with their hats on, hands stuck in pockets and pipes in mouths as the cortege passes as was the case on Saturday last at Colne when the Titanic’s Bandmaster Hartley (of splendid memory) was buried. Let every man, who is a man, show his sympathy and respect by uncovering as the funeral goes on its sad way. Many there will be who will pray that she shall Rest In Peace.

Not since the funeral of little Alice Barnes twenty years ago had there been scenes and a demonstration of public interest and sympathy such as occurred in the town of Blackburn at the funeral of the once radiant and beautiful Alice Beetham.

All morning folk viewed the body at 24 Billinge Street, and young girls added any number of small bunches of flowers to the large wreaths sent by workers at the Jubilee mill, friends and relatives. The coffin, placed in the front kitchen of the house, was swamped by the tokens of tender regard. A collection held at the mill raised a record sum part of which was given to Alice’s family and the rest purchased the workers’ wreath of red and pink roses surrounded by arum lilies, lilies of the valley and white carnations intermingled with fern and ivy leaves. Arum lilies, one from each member of the family, were strewn on Alice’s body as it lay in the smart coffin of polished panelled oak with silver fittings. On the plate was inscribed ‘ALICE BEETHAM, Died May 20, 1912, Aged 18 years. R.I.P.’

A memorial card was prepared for the family. On one side was a cross with ivy intertwined and the lines…

In thee have I hoped

O Lord,

I shall never be

confounded

The other side featured prayers of the Roman Catholic Church to which Alice belonged.

Scales and Son of Copy Nook had been chosen to arrange the funeral which took place on Saturday, 25 May 1912. It was a fine and sunny day for the most part with temperatures around 58° Fahrenheit or thereabouts.

‘In Loving Memory of Alice Beetham’. Northern Daily Telegraph

A spotlight of sunlight greeted the Beetham family as they emerged from the house that day. Alice’s mother was quite obviously distraught and had to be practically carried to the coach supported by her husband and Father Cobb. Once inside, she swooned and became weak and faint. A glass of water temporarily revived her.

Alice’s father was also showing signs of great emotion and her two little sisters, Lizzie and Isabel, sobbed out loud crying ‘Oh, Alice! Oh, dear!’ Nearby, six-year-old brother Joseph quietly sobbed too.

The solemn procession left the house at 2.20 pm. All along the route to Blackburn cemetery, situated off Whalley New Road, crowds lined the way and all the men present did indeed remove their hats and caps. Alice’s mother was still in a state of collapse, unaware of the constant stream of ‘outsiders’ trailing from the railway station to witness events that day and, maybe, pay their respects to her daughter. Amazingly, a special two-minute tram service had been laid on from the town centre to the cemetery and every single car was full.

With crowds gathered as far as the eye could see, a short service took place in the Catholic chapel before the procession wended its way to the graveside. Alice’s mother had to be supported again and was almost in a state of stupor as the last rites were read. She was not alone as many of the mourners present were also, to a greater or lesser degree, overcome. At 54 Riley Street, Blackburn, Arthur Birkett’s home, the blinds were drawn both up and downstairs.

On Thursday, 30 May 1912, Birkett appeared before the Borough Police Court charged that he ‘feloniously, wilfully and of malice aforethought did kill and murder Alice Beetham in a weft warehouse at the Jubilee mill, Gate Street, Blackburn, at about 8.45 am Monday, May 20, 1912’. Birkett looked pale and ill having only been discharged a little earlier that day from the infirmary. He was subsequently remanded in custody.

On the resumption of the inquest it was all too clear to the jury that there was a case to be answered by Birkett. A verdict of wilful murder resulted in him being committed for trial at the Manchester Assizes with all the witnesses in the case bound over to appear. A dazed, silent and somewhat bewildered Birkett was led away purposefully from the dock. He was transferred from the police station later that day to Preston gaol.

Arthur Birkett – quiet but pleasant. Northern Daily Telegraph

The trial of Arthur Birkett took place at the Manchester Assizes on 5 July 1912 before Mr Justice Bucknill. Counsel for the prosecution was the forty-two-year-old, short, rotund and already very well respected Gordon Hewart together with A R Kennedy. Hewart had a reputation for clarity of thought combined with cool and deadly presentation of evidence that boded ill for any defendant. He was later appointed Solicitor-General by Lloyd George in 1916 after turning down the Home Office. A knighthood followed and the post of Attorney-General in 1919.

It was as Attorney-General that Gordon Hewart took the leading prosecution role in the trial of Ronald Vivian Light at Leicester Castle Court in the legendary case of the Green Bicycle murder in 1920. This crime is probably second only to the Wallace murder case in Liverpool in January 1931 in terms of unbeatable puzzlement and mystery. Mr Lindon Riley, instructed by Blackburn solicitor Harry Backhouse, appeared for the defence.

Arthur Birkett, wearing a dark navy-blue suit and black tie, pleaded ‘not guilty’ to the charge of murder in a firm voice. Gordon Hewart for the prosecution outlined the case… Birkett thought himself deeply in love with Alice Beetham, they’d been ‘walking out’ together. Mrs Lily Wragg, a weaver at the same mill and a joint friend, would say that after the couple had fallen out Birkett had visited her announcing Alice had ‘chucked’ him. Lily Wragg and her husband then heard Birkett say he would ‘Chop her … head off!’ Lily had told him not to be so silly. Birkett then said he and Alice had been to the pictures where a film had shown two lovers quarrelling. He’d enquired of Alice ‘We’re not like them, are we?’ She hadn’t replied but simply shook her head. Birkett commented ‘I hope the next one she gets she will like!’

One day early in May 1912, continued Gordon Hewart, Arthur Birkett had conversed at the Jubilee Mill with a woman called Slater. He’d said ‘It’s surprising what some men will do for women…There is only one girl for me and if I don’t get her I will have no one!’ Slater agreed that Alice Beetham was indeed a good girl ‘no matter who gets her!’ Hewart then went on to describe the course of events leading up to the murder and ended his preliminary address devastatingly with the words – ‘It was a cool, premeditated, deliberate act, the details of which were clearly and accurately recollected by the prisoner himself!’

The defence pleaded eloquently on behalf of the accused and for mercy to be shown in his case but they faced impossible odds – a watertight prosecution case put to the jury by a master of the art of bringing a defendant’s sins irrefutably home to him.

The judge’s summing-up was generally against Birkett. He told the jury that the only question they could ask themselves was whether the crown had made out to their satisfaction that Birkett was guilty of wilful murder done knowingly and maliciously. In the absence of an explanation by him to the contrary they were entitled to infer that he did it willingly and of malice aforethought.

The jury retired for just fifteen minutes before finding Arthur Birkett guilty as charged. Donning the black cap, the judge told him he had been found guilty of a very cruel murder which had been premeditated and determined. Mr Justice Bucknill stated that he thoroughly agreed with the verdict and went on to tell Birkett ‘You have forfeited your life. Make peace with your Maker, I implore you!’ A young woman then screamed piercingly and fainted dramatically at the back of the court. At the same time Birkett collapsed and had to be carried below by two warders. The ongoing serial in the local Northern Daily Telegraph at the time was suitably titled ‘Fate and The Man’.

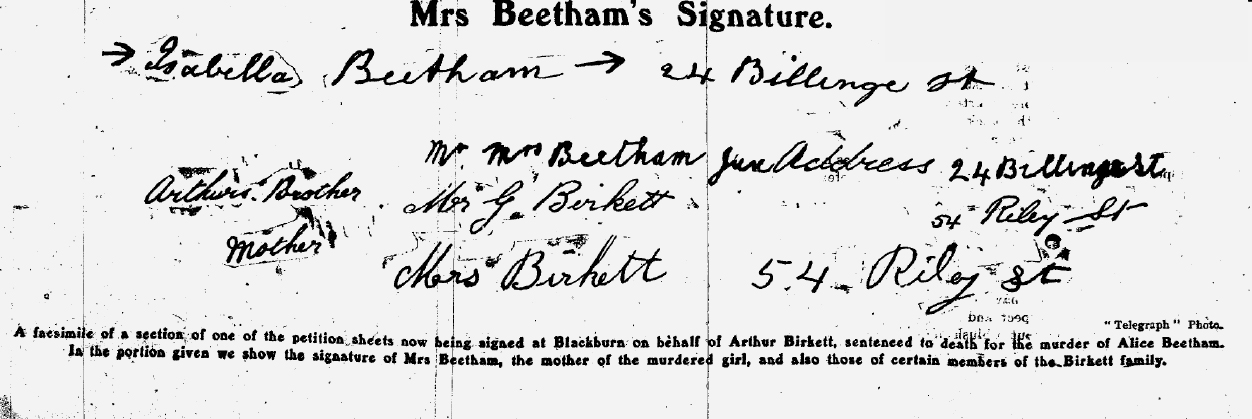

By 15 July petitions instituted to save Arthur Birkett had been signed by over 50,000 people. Amongst them was Mrs Beetham, the mother of the dead girl, who had added her signature two days earlier. Alienating hate from her shattered and broken heart she somehow summoned the grace, courage and forgiveness to do so. How many of us could have done the same, I wonder? Letters for and against a reprieve appeared in the press and by 18 July the petitions, now signed by some 66,000 folk, went off to the Home Office.

Birkett: A petition for reprieve signed by Mrs Beetham, the mother of the murdered girl. Northern Daily Telegraph

At Strangeways prison on 17 July Arthur Birkett was visited by his mother, Mrs Beetham and, oddly, one Jack Grierson – a well-known entertainer of the day. The whole party exhibited signs of grief and distress on emerging from the meeting which lasted over three-quarters of an hour. It took place in the library of the gaol.

Birkett repeatedly asked Alice’s mother whether she’d forgiven him and was told ‘Rest assured. I have forgiven you long since!’ Birkett eventually calmed down and said he was very thankful for her visit. Mrs Beetham murmured ‘Poor lad, poor lad!’ again and again. All Birkett would speak of initially was Alice but, finally, he enquired regarding the petitions saying he would like to be spared if only for the sake of his mother. Absurdly and inadequately, he said he was sorry for the ‘trouble’ he’d caused. At the parting of the ways no one could speak for they were so full of emotion. Birkett got up to go and finally found his voice, apologising for not shaking hands as it was not permitted by the prison authorities.

The Home Secretary, Reginald M’Kenna, replied to the petitions he’d received on Birkett’s behalf on 20 July. There were, he concluded, insufficient grounds to justify his advising His Majesty to interfere with the sentence of the court in Birkett’s case. At 8 am on Tuesday, 23 July 1912, Arthur Birkett was duly hanged on a dismal, rather cold day. Ellis was his executioner and five or six thousand folk waited while his fate was sealed. They milled around expectantly outside the prison gates till it was all over. The body was later interred within the precincts of the gaol.

The scene in Riley Street, Blackburn, at the time of Arthur Birkett’s execution. Northern Daily Telegraph

A warder putting up the notice announcing the sentence of death on Arthur Birkett had been carried out. Northern Daily Telegraph

The crowd at Strangeways gaol reading the notice of Birkett’s death. Northern Daily Telegraph

On the morning of the execution a service was conducted at 54 Riley Street, Blackburn, by the vicar of St Thomas’s, the Reverend F G Chevassut. Safe In The Arms Of Jesus and God Be With You Till We Meet Again were among the hymns that rang out from the sombre congregation. A Salvation Army officer stood on a chair in the street to address the assembled crowd and Alice’s mother, family and friends appeared in the doorway engendering much emotion in everyone present. There was an ‘elegy’ printed later in the papers that ran…

Mourn for the maid, the lad

and his doom,

Weep at the warp that tore

in the loom,

Wail for the wool that

wove such a pass,

Greet o’er the graves of

love and the lass.

O weave not, Black Fate,

such fabric again

Of love-stricken youth and

his lady disdain

By J Walsh, Blackburn.

The baleful and long-forgotten murder in the mill was perhaps a blueprint for the Guy Fawkes night killing in Rishton fifteen years later in 1927. Arthur Birkett and Fred Fielding were almost certainly of a type – selfish obsessives both. They failed miserably to understand that true love never kills but nurtures – whether returned in kind or not…

Love seeketh not itself to please

Nor for itself hath any care;

But for another gives its ease

And builds a Heaven in Hell’s despair

William Blake, 1794