Lower Cunliffe, Rishton, where part of the dismembered body of Emily Holland was discovered. The author

On the morning of Thursday, 30 March 1876, Mrs White of Bastwell Terrace, Blackburn, was out walking. In a field at the rear of her home and some one hundred yards from Whalley Road, Blackburn, she came upon a portion of the body of a young child wrapped in newspapers. Minus head, arms and legs, her ghastly find had been deposited in what was a quite open area. The field was overlooked by the rear of property on Bastwell Terrace and in front by a row of substantial houses known as Crescent View. Near at hand were a small plantation and the River Blakewater. The horrified woman called over a passer-by, Richard Dewhurst, a clogger of Whalley Road. Soon after, he hurried away to fetch the police.

PC Rostron of the local force promptly arrived, marked the spot and took the remains in a basket to the police station where they were unwrapped and examined. The torso had been enclosed in two copies of the Preston Herald dated 14 and 18 March 1876, the papers being heavily bloodstained. On closer examination, short dark and white hairs were found attached to the trunk in some quantity.

While the police were still puzzling over the morning’s gruesome find sensational news followed that same afternoon from Lower Cunliffe, Rishton. In that district a man named Richard Fairclough had discovered in a drain the legs of a child wrapped in two copies of the Preston Herald newspaper dated 25 March and 10 November 1875. The legs were found to fit perfectly the trunk from the field at Bastwell, Blackburn, that of a child, female, about seven years of age. An extensive search began to find the missing arms and head.

The post-mortem examination of the trunk earlier in the day revealed that the child had been sexually assaulted prior to killing and dismemberment. In the view of the medical men, her throat had been cut and she had subsequently bled to death. It was all horribly clear – a case of child assault, murder and then, within hours, dismemberment of the victim’s body. The detectives assigned to the case soon discovered the following facts.

Lower Cunliffe, Rishton, where part of the dismembered body of Emily Holland was discovered. The author

The victim’s name was Emily Holland, seven years of age, of 110 Moss Street, Blackburn. She had been reported missing since the afternoon of Tuesday, 28 March, by her worried parents. They were called and identified the mutilated remains of their daughter. The young girl had been coming home from St Alban’s RC school on the 28th about 4.15 pm and Mary Eccles, twelve years of age, stated that she had spoken to Emily around that time in Birley Street which adjoined Moss Street. Emily had said she was ‘going to fetch half an ounce of tobacco for a man in the street’. These words were misconstrued by Mary Eccles and later the police to mean a tramp or beggar who was about in Birley Street at the time. Their true interpretation would only become clear later.

Men in the street, itinerants of every kind, abounded in those days. The Daisyfield and Brookhouse areas of Blackburn had their fair share of them. Mary Eccles described a man she had seen in Birley Street at the time of her conversation with Emily Holland as about forty years old, five feet six or seven inches tall, with dark hair. He was wearing a mixture coat, black dirty trousers and clogs cut open and down at the heels. Other children stated that they had seen such a man in the neighbourhood that day and one child was certain the tramp and the little girl went off together after she returned to him with the tobacco. A number of adult witnesses had noted the presence of such a man and the hunt for him became the first priority of the police under the Lestrade-like Chief Constable Potts.

St Alban’s RC Church, Blackburn, where the Holland family worshipped. The author

The first beggar to be arrested under suspicion of being the murderer of the child was apprehended at Clitheroe but this man was later released as he clearly did not match the description given by the witnesses. That description was rapidly printed and posted throughout the Blackburn area.

During the next few days, with the realisation that such a horrible crime had been committed in their midst, the populace of the town were roused to tremendous indignation and anger. Likewise, the people of Accrington and district, particularly in Rishton where the legs had been found, were outraged at the terrible fate that had overtaken young Emily Holland. The police received the utmost co-operation from the public in their endeavours to trace the man in the mixture coat and dirty black trousers who was the prime suspect in the case. Tramps and beggars were apprehended from as far away as Ormskirk, Leeds, Todmorden and Bolton. Others were taken into custody nearer to hand in Accrington and Blackburn. Many of the ne’er-do-wells probably had petty thieving and the like on their conscience but none, finally, were charged with the murder of the little girl. After a few days they were set free, able to resume their nomadic lifestyles amongst more honest folk.

The post-mortem examination of the remains had revealed, in addition to the evidence of assault and cause of death, that the stomach contained only partially digested food. As her last meal had been eaten around 1 pm on the day of her disappearance and since she had been seen alive at past 4 pm the examining doctors concluded that the little girl had been murdered very soon afterwards. They were also of the opinion that the dismemberment of the body had been carried out by someone who had ‘some skill in amputation’.

The police carried out a search of houses in the Brookhouse district of Blackburn in the hunt for the head, arms and clothing of the victim whilst continuing their investigation of drains, ditches and wasteland in the vicinity of Moss Street, Bastwell and the Lower Cunliffe area of Rishton.

It was now a week since Emily Holland had been butchered and the police ‘tramp theory’ was beginning to look a little thin to an angry and expectant public. There were, even to the layman’s mind, several serious objections to it. In the first place, despite a comprehensive and intense search covering a wide area, no indication of where the murder had been committed could be found. If such a spot were indeed outdoors it would certainly have been discovered within the week by police or public. The inevitable conclusion to be drawn was that the murder and mutilation had been wrought indoors. Yet what secluded lodgings could a travelling tramp be expected to have at his disposal to perform such ghastly business unseen or unheard? And would he then secrete the dismembered remains there for nearly two days before disposing of them and resuming his wanderings? Surely, he would have departed the scene of the atrocity as soon as possible.

Then there was the established fact that the trunk and legs had been found wrapped in copies of local newspapers, one of them more than a year old, which a passing tramp would surely have found hard to come by. The other equally significant fact was the presence of several varieties of short-cut hair found attached to the trunk indicating the remains might have lain awhile on the floor of a barber’s shop or the like. All this pointed to the murder not only having been committed indoors but also by a man who was resident in the district.

The general public were becoming increasingly restless as were the crowds constantly milling around Blackburn police station hoping for first news of developments in the drama. They could see, even if the police could not, that the all-out effort to produce a beggar who fitted the witnesses description and could be shown to have been in the town at the time of the murder was likely to go unrewarded. And even if such a man were to be found it might prove a difficult or impossible task to obtain damning evidence against the wretch.

It was on Wednesday, 5 April, that Chief Constable Potts, who had been collecting tramps like other people collect stamps, finally heard news of what seemed a veritable ‘penny black’. It came from further afield than ever – Ashbourne in Derbyshire. The local superintendent of police, named Whieldon, had been reading the description of the wanted man in the Blackburn case when an unlucky vagrant passed by his window – a man in the wrong place at, for him at least, the wrong time. The fellow was quickly apprehended by the sagacious superintendent and taken into custody. He gave his name as Robert Taylor. (His namesake was to play an important and sensational part in the case at a later date)

Mary Eccles identified Robert Taylor as the beggar she had seen in Birley Street on Tuesday, 28 March, and other juvenile witnesses agreed he was the wanted man. Significantly, certain of the adult witnesses failed to recognise him and stated they doubted he was the tramp they had seen on that fateful day. Not to be dissuaded, the Chief Constable charged Taylor on Monday, 10 April, with the assault, murder and mutilation of the child. He was a pathetic figure. Bewildered, unkempt and shabbily dressed, he stood some five feet seven inches tall. His brother who was brought to identify him duly did so but went unrecognised by Taylor himself. The doctors who examined him stated he was a lunatic and possibly dangerous. The butchering of Emily Holland, however, done with some skill and a deal of cool deliberation, could not be easily ascribed to a frenzied lunatic and popular opinion was that the degenerate had yet to be found. Nevertheless, the police had their man. They were shortly to discover he was the wrong man.

During the course of their investigation the police had searched a number of premises on Moss Street and the streets adjoining. Popular suspicion rested on two shops in particular in the neighbourhood of the dead girl’s home. They were both barbers’ premises. The short-cut hair attached to the torso of the victim was established, at least to the satisfaction of everyone save the Chief Constable, as likely to have originated from the floor of such a shop. At the adjourned inquest Potts had sought to make light of this aspect of the case and it was clear that he himself attached little importance to it. Undoubtedly, it was the restless crowds outside the police station that forced the authorities to take the general suspicion concerning the two shops seriously.

Moss Street, Blackburn, today, looking towards the town centre. The author

Logically, the more suspect shop would have been that of a man named Dennis Whitehead in Birley Street, if only because five single men had lodgings there at the time of the outrage. However, the intense local feeling was directed more towards the other shop and its occupant.

The business located at 3 Moss Street, was run by one William Fish. The ‘shop’ was virtually an ordinary terraced house at the end of the street nearest the town centre about half a mile distant. Fish had occupied the premises for twelve months or more, first living there with his wife and two children. Latterly, the family had moved out to live in a house further down the street at number 162 – on the same side a little way down from the house occupied by the Holland family. The shop at number three was therefore used solely as a workplace at the time of the murder.

William Fish was a small man, approximately five feet three inches tall, who had a fondness for rough tobacco and a pipe. Some twenty-six years of age, he had an unfortunate history. He was born locally in Darwen but his mother had died when he was young and his father was unwilling or unable to look after him. Consequently, he spent his formative years in the Blackburn workhouse till, at eleven years old, he was apprenticed to a barber, the Dickensianly-named Mr Chadwick Bramley whose shop was situated in Northgate, Blackburn.

Fish ran off but subsequently returned to his employer who readily accepted him back to resume his apprenticeship. In 1869 Mr Bramley had cause to regret his good nature for Fish stole £3 from him – a substantial sum in those days – and spent a fortnight behind bars for the offence. On his release he independently set up shop in the town, renting a number of different premises before settling to his trade in Moss Street.

The police first searched Fish’s shop on Saturday, 1 April, soon after the discovery of the torso and legs. The three officers, Detective Swesey, Sergeant Pickup and Superintendent Eastwood, told Fish it was a routine check and that they had no suspicion of him. He was again visited by Eastwood and Swesey the following day and questioned as to his movements on the day Emily Holland had gone missing. His account proved satisfactory. However, in response to increasingly hostile public opinion, his premises were again searched on 3 April by the indefatigable if inept Eastwood, Detectives Holden and Stewart along with the Chief Constable himself. For good measure and at Fish’s invitation the police also searched the family home at 162 Moss Street – all to no avail.

At the end of this third examination of his premises Fish appealed for police protection and Chief Constable Potts obliged by publicly announcing to the crowds gathered outside in Moss Street that nothing had been found and Fish was as innocent as he was of the terrible crime. The police did, however, uncover a very singular piece of circumstantial evidence which to everyone but the Chief Constable incontrovertibly implicated Fish in the murder of the child.

The diminutive barber regularly took a number of local newspapers and these were piled together on a shelf in his shop. Four issues of the Preston Herald corresponding with the dates of those used to parcel the torso and legs of the victim were missing from an otherwise complete set of that paper. Asked to account for the missing copies Fish claimed to have used them to light the fire. Chief Constable Potts, still pursuing his tramp theory almost to the exclusion of common sense, found Fish’s explanation perfectly plausible at the time.

William Fish, vindicated publicly by the Chief of Police, continued to go about his business. During the first few days of the investigation he had readily discussed the murder with the customers in his shop. Now, despite being cleared of any involvement in the case, he found himself hounded by still sceptical neighbours and with no clientele.

As the missing arms and head seemed unlikely to be located in the near future the decision was taken to inter the discovered remains of Emily Holland without further delay. The funeral procession wound its way sadly and silently down Moss Street. Fish sat and watched with the door of his shop wide open, smoking a pipe of his favourite tobacco. (perhaps, in cruel disrespect, that purchased by the little girl for ‘a man in the street’).

Interested but unconcerned, Fish seemed at his ease. No doubt when he learned of the arrest of the deranged tramp Robert Taylor he felt further reassured. Public opinion, however, remained intensely hostile towards him and the police were obliged to renew his acquaintance when they received an extraordinary offer of assistance from an unexpected quarter.

William Fish. Famous Crimes, 1900(?)

Peter Taylor, a painter, of 72 Nelson Street, Preston, had two dogs in his possession. One of these was a springer spaniel and the other a half-bred bloodhound named Morgan. Taylor boasted to his friends that his dogs would soon uncover the missing remains in the Blackburn case – if they were put to the test. To prove his claim he offered their services to Chief Constable Potts and, unexpectedly, the offer was taken up. It was arranged for Peter Taylor to put his dogs to work in the vicinity of the Bastwell area and Lower Cunliffe, Rishton, where the remains had been found.

By then, a reward of £100 from the Home Secretary and a similar sum from the town council had been proffered. The case was receiving nationwide coverage in the press. No doubt Chief Constable Potts accepted the offer of help from Peter Taylor to make it clear to all and sundry that he was still investigating every possibility. Privately, he firmly believed he already had his man in custody.

The two dogs went to work on Sunday, 16 April and, disappointingly, discovered nothing. They returned with their dejected master to the police station whereupon it was decided as a last recourse to try them at the shops of the two barbers, Dennis Whitehead and William Fish.

Detective Livesey took possession of Whitehead’s shop whilst Holden, his colleague, called on Fish and his wife. He asked them to accompany him to the shop at 3 Moss Street. Superintendent Eastwood, with Peter Taylor and the dogs, first searched the Birley Street premises and found nothing to arouse suspicion. They then moved on to Moss Street where Fish, noting the presence of the animals, suddenly became agitated and uneasy. Morgan, the cross-bred bloodhound, had sniffed and snuffled about the place without success, finally wandering into the front bedroom facing the street.

In front of the fireplace he started to bark excitedly and could not be pulled away from the spot without difficulty. Peter Taylor placed his head and body into the chimney opening and reached upward. In a small recess his hand touched upon something. He pulled it down and exposed a bloodstained parcel made up from a copy of the Manchester Courier, its date being obliterated.

The contents of the parcel were in fact various fragments of a human skull, hands and forearms. Though partially burnt, hair was still attaching to the skull. In addition there were small fragments of calico found in the grate matching those of the dress Emily Holland had worn on the day she disappeared. William Fish, stunned and stuttering, denied any knowledge of the parcel and its appalling contents. His wife, however, was deeply affected and had to be supported by the detectives.

At the front of the shop a large crowd had congregated. Though the police had tried to undertake the searching of the premises inconspicuously, news of their activities had spread all too rapidly. The besieging throng was in an ugly mood. There was no possible chance of Fish being removed unmolested from the front of the premises so he was surreptitiously spirited away via the rear of the shop to the police station and the cells. Peter Taylor and the dogs returned to Preston to receive quite an ovation from the townsfolk.

News of the barber’s arrest echoed around Blackburn and the surrounding area. Excitement reached fever pitch. The annual Blackburn Easter Fair taking place that same week was virtually ignored as folk milled around Moss Street and the murderer’s seedy shop. They even visited the house of the victim’s parents where many left money in sympathy. Downstairs, the Hollands’ home was open to the public even though the family were present – save for the utterly distraught mother who was ill and inconsolable upstairs.

The Borough Arms, Blackburn — where prime suspect Peter Taylor found sanctuary on his release by the police. The author

Early on the following day, Monday, 17 April, the police at long last thoroughly searched Fish’s shop. Sure enough, other items of evidence were discovered including, under the coals, a clearly recognisable portion of the child’s dress. Later that day, after being remanded by the magistrates, William Fish confessed to his odious crime.

Chief Constable Potts took down his statement which detailed how Fish had sent the child for tobacco and, on her return, cajoled her into the empty shop and upstairs where he viciously assaulted her. He had cut the near-dead girl’s throat with a razor and she had quickly bled to death. Later, he had cut off the head, arms and legs of his victim. He then parcelled the torso and legs before disposing of them at Bastwell and Rishton. The arms and head were put in the fire in the front bedroom as were pieces of Emily’s clothing. However, a portion remained unburnt and on the Saturday following Fish had wrapped up these grisly remnants and hidden them in the chimney where the persistent bloodhound caused them to be found.

Fish further stated that no-one else had played any part in the horrible proceedings thus completely exonerating the pathetic tramp Robert Taylor who still languished in police custody. He was later released – apparently unaware of the terrible position in which he had been placed. Bewildered, he left the Town Hall escorted by two of his brothers and was heartily cheered by the huge crowd assembled in the street. He tottered gratefully into the nearby Borough Arms public house and once more into anonymity.

After the arrest of Fish the local papers, whose circulation had increased fivefold during the course of the investigation, featured articles castigating the police and the Chief Constable in particular. Not only had the action of the authorities resulted in an accusation being made against an entirely innocent man but the inept searching of Fish’s premises had offered him the opportunity, though he did not take it, to dispose of any incriminating evidence against him.

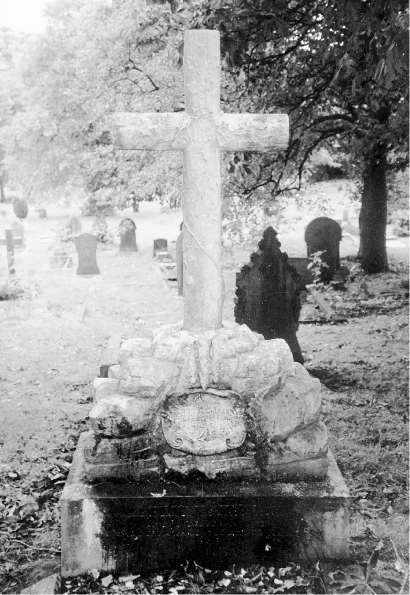

The grave of Emily Holland, Blackburn cemetery. The author

Chief Constable Potts found himself not only the subject of considerable criticism but also something of a figure of fun. A conundrum was composed that posed the question: ‘When was Mr Potts like the beggar Lazarus?’ Answer: ‘When he was licked by dogs!’ Fish too was the butt of many a jest. One such suggested he was a member of the Herring family – ‘those that had to be hung before they could be cured!’

The police returned the keys to 3 Moss Street, to the owner of the property, Mr Walton, on 26 April. With an eye to business he put the place on view to the public at 3d a time. This entrance fee was, he said, to be divided equally between himself, Fish’s family and the family of the victim. It proved to be a profitable enterprise.

Scroll on Emily Holland’s grave. The author

Press from all parts of the country attended the resumed inquest on Thursday, 20 April, when Fish’s confession was first made public. The murderer was apparently full of remorse in the dock but found himself continually hissed and hooted at during the proceedings. He must have been thankful that he was not in the hands of the incensed and infuriated townsfolk.

The trial of William Fish at Liverpool Assizes on Friday, 28 July 1876, was presided over by Mr Justice Lindley. The accused pleaded ‘guilty’ to the charge of wilful murder brought against him. It was established beyond any reasonable doubt on the evidence of the medical witnesses that Fish was not suffering from mania or any other condition that might prevent him from knowing what he was doing. He was duly sentenced to death and on Monday, 14 August, and was executed at Kirkdale gaol. As they strapped his legs together prior to the drop it was said he was overcome with terror. It was a fitting emotion on which to end an unworthy life.