Mrs Westwell, the victim of the crime. Accrington Observer and Times

Any chapter on the above dealing with the Blackburn and Hyndburn areas would be incomplete without some mention of the Susan Westwell mystery which occurred on the night of Wednesday, 24 August 1904.

A special edition of the Accrington Observer and Times was produced on the day following the tragedy, news of which created a sensation in the town. Mrs Westwell was seventy-eight years of age and well-known in her local community. For some thirty years she’d lived at 24 Hyndburn Road, Accrington, opposite Ellison’s Tenement which served as the fairground for the town. Near at hand were Entwisle’s mill and the local gasworks.

It was 6 am on the morning of 25 August when the old lady was found behind the front door of her house in a dying state – her skull fractured, her head battered in by the ubiquitous ‘blunt instrument’ and a blackened right eye with a lump the size of an egg over it. She was unconscious and died within a few minutes of being found.

No blood was found on anything resembling a possible weapon within the property and a number of copper coins were lying underneath the body. Drawers had been pulled open and it seemed the place had been systematically ransacked. Mrs Westwell was fully dressed when found, her bed had not been slept in and the gas was burning bright in the front room downstairs. Significantly, the back yard gate was found unfastened and the back door open a foot or so.

Susan Westwell was said to have been ‘a little peculiar in manner’ and earned a little money supplying hot water and making tea for the millworkers nearby. She was generally regarded, however, as being better off than most and always had loose cash secreted in odd corners about the house. In an old can filled with dry soap packets and the like, was found £5. The fireplace, when searched, revealed a canister containing £1 in copper. In a bucket under the stairs was a piece of paper under which was an old saucer. Under the saucer was found a shilling (5p). Mrs Westwell also habitually carried money in a purse made out of a stocking foot fastened with a safety pin but this was missing.

Mrs Elizabeth Buckley of 7 Grant Street, Accrington, was a friend of Mrs Westwell and called on her on the night of the murder around 9 pm. She had talked with the deceased on her doorstep and noted the presence inside the house of two young men of about twenty years of age – one sitting at the table, the other at the fireplace, but both with their backs to the front door.

Mrs Westwell, the victim of the crime. Accrington Observer and Times

The postmortem examination conducted by Doctor Greenhalgh and Doctor Geddie junior revealed Susan Westwell had been attacked during Wednesday night and had been unconscious some considerable time. Death, not surprisingly, had been the lingering result of a wound at the back of the head where the bone was splintered with flesh adhering to it.

One cottage next door to Mrs Westwell’s was unoccupied at the time of the murder and no undue noise had been heard or noted by the remaining next door neighbour.

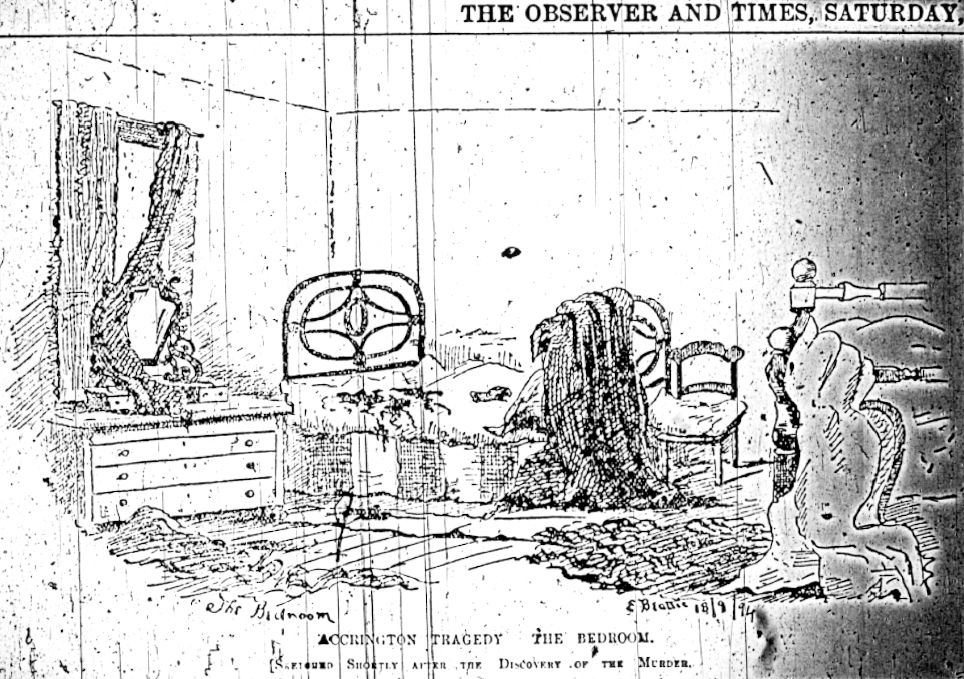

The murder room was described as follows:

The room was sanded over. A chest of drawers and a dresser occupy the two sides of the room and are surmounted by the usual working-class ornaments. Pictures on the wall are scriptural subjects and family photographs. Place of honour though was given to a lithograph of Gladstone.

As to Mrs Westwell’s personality, she was described as ‘careful and thrifty’. Few could excel her in household management. She had very frugal habits, it not costing her two shillings (10p) a week to live besides the necessary three shillings (15p) rent on the property.

The description and circumstances of Susan Westwell’s life are almost as appalling as the old lady’s brutal demise. Life for the citizens of Britain’s well-defined working class at the beginning of the twentieth century was grim and unforgiving. To think that an elderly woman of seventy-eight still had to earn a living then or, at least, was afraid of not doing so, is sad to contemplate.

To read of the very basic living conditions Susan Westwell, like many others, had to endure is one thing. To see the things she no doubt held dear patronisingly referred to as ‘the usual working class ornaments’ and the place of honour given to the lithograph of Gladstone mocked adds bitter insult to injury.

There were few clues as to the perpetrators of the crime and it was commented upon locally that ‘It may forever remain a mystery unless somebody blabs!’ It would appear that the old lady was engaged in money-lending to boost her income and it was one or perhaps several of her clientele that were responsible for her murder. One of her friends stated at the time that she was afraid of being attacked. Yet, on the evening of the crime, she had clearly admitted two young men to the house.

The brutal murder was infact never solved and on 31 May 1939 the house at 24 Hyndburn Road, Accrington, was demolished along with several others taking its secret with it from the dog-days of 1904.

A few minutes before 6 am on Tuesday, 18 September 1894, Richard James Farrar, a yarn-dresser employed at F Steiner and Co, went off to work as usual – quietly closing the door of the family home at 43 Hyndburn Road, Accrington, behind him. Left in the house were his wife, Alice Ann, and children Esther Hannah (8), Ellen (6) and Isabella, just three years old.

Later that morning the nextdoor neighbour heard the children at number 43 screaming. Knocking on the bedroom wall, there was a loud knock in response which seemed to indicate everything was alright. However, as the blinds of the young couple’s house remained drawn and everything had gone strangely, eerily quiet the neighbour again became worried and uneasy.

The key of a neighbouring house was found to open number 43 and a few concerned folk entered the silent property and made their way upstairs. They probably feared the worst by then and they were destined not to be disappointed.

The fully clothed figure of Alice Ann Farrar was draped across the foot of the bed and by her side was an open razor. The three children were in the bed – the eldest, Esther Hannah, quite dead. Her throat had been cut and the jugular vein severed. The other two children had deep gashes in their throats and were bleeding profusely. Yet, by a miracle, they were still alive. Closer examination of the mother showed that she too had a wound to her throat which was described as ‘terribly hacked’ due to the jagged edge of the razor.

The bedroom shortly after the discovery of the tragedy. Accrington Observer and Times

Doctors Cowie and Geddie, having pushed their way through the large crowd that had gathered outside the small terraced house, treated all the parties involved in the tragedy.

A message relayed to Richard Farrar at his work sent him hurrying home. He arrived just as the police were removing his wife in a cab to the police station. He didn’t enter the house but was taken to that of his sister nearby in Steiner Street. The two children who were still alive were rushed to the Blackburn Infirmary. Clearly, as she had been taken to the police station rather than the hospital, the mother’s injuries were not as bad as those of her offspring.

When a weeping, grief-stricken Richard Farrar visited his wife later at the police station she used these words of explanation:

Oh, Dick, it came over me and I could not help it. Something came over me here and said ‘Do it!’ so I went downstairs, locked the front door and put the key on the dresser. Then I went back upstairs with the razor, cut the eldest child while she slept, then the baby and then the other girl. This one struggled with me hard so I kneeled astride her and had to master her in that way. By that time my strength had almost gone. I cut my own throat but I was so weak that I could not cut myself deep enough… Oh, Dick, it’s a bad job! Where are my children, bless them?

Alice clung to her husband and asked him to forgive her.

Alice Ann Farrar was thirty-one years old and had been born and brought up at the remote Top o’th Bank Farm near Bacup. She had married her husband when twenty-one on Christmas day at the Ebenezer Baptist Chapel in the town. The couple lived at Wear Bottom up the valley from Bacup and Dick Farrar worked at the Irwell Spring Dye Works. He soon attained the position of Overseer at a good wage for the times of twenty-six shillings (£1.30) a week. Their first child died at nine months old but even when the the other three children came along the family remained comfortably off in the circumstances.

A shattering blow to the Farrar family came with the closing of the dye works in 1892. Dick Farrar had to think himself lucky when he was offered a position as a labourer at Steiner’s Church works. On his accepting the job, the family had moved to the house in Hyndburn Road, Accrington.

The family’s downturn in fortunes preyed on Alice’s mind. Her husband’s big reduction in wages turned her into a niggardly woman bent on saving every penny wherever and whenever possible. She denied herself meals and gave birth again during this period but the baby died when very young. This seemed to act as something of a last straw to Alice and her psyche became disturbed.

Alice Ann Farrar. Accrington Observer and Times

Melancholy and undue fretting over the slightest domestic problem became natural to her. She developed eccentricities of speech and conduct which so alarmed her husband that he insisted she seek help. Whilst not a matter of fact, it is fairly certain that Alice attempted suicide in her frail state of mind at this time. After the awful events of 18 September 1894, Alice Ann Farrar was sent to a lunatic asylum.

Society in those days was always disposing of its unfortunates in the prison, the workhouse or the asylum and with no welfare state to intervene on their behalf all too many honest hardworking folk, undeserving of such a fate, nevertheless found it impossible to avoid one or the other of the cess pits of humanity awaiting them.

Once her husband’s job went with the closing of the dye works; when she had to cope in reduced circumstances on much reduced housekeeping; when yet another child died in infancy; when her health deteriorated due in part to her own neglect of herself; when the government, as usual, couldn’t have cared less; when there were no social workers, stress counsellors or seemingly a shred of hope left for the future then, not altogether surprisingly, Alice Ann Farrar’s mind boiled over into turmoil and fatal distraction. There must have been many working folk with large families in those desperately hard times who whispered to themselves under their breath… ‘There but for the grace of God go I!’

At Duckworth Hall, Oswaldtwistle, some 200 yards from the Britannia Inn along the old highway leading from Blackburn to Haslingden, stands The Brown Cow inn or beerhouse as it was known in 1880.

In February 1880 The Brown Cow was occupied by seventy-four year-old farmer and beerseller John Garsden and his wife who was at least sixty years of age. The only other person in the household was their fifty year-old cowman and manservant Robert Hartley.

On Wednesday, 11 February 1880, John Garsden travelled to Blackburn with the intention of buying some cattle. The livestock trading must have gone well for he returned about 6 pm that day ‘a little the worse for liquor’. It did not stop him partaking of a drop or two more in his own kitchen during the rest of the evening when the Garsdens had company. He must have been barely able to stand by the end of that long, exhausting day.

At around 9 pm in the evening Robert Hartley went into the front parlour, a room rarely used by the family, to wind up the clock. As usual, there was no fire lit in the room. Careful to place his candle securely on the fireplace he completed his task, removed the candle and left – fastening the door by dropping a hook on the outside into an iron loophole. He lit a fire in the Garsdens bedroom and Mrs Garsden came up to bed, followed uncertainly by her husband. Locking the doors of the premises, Hartley then retired to bed himself.

Mrs Garsden was suffering from a heavy cold and found it difficult to drop off to sleep which proved a godsend when, around 10.30 pm, she became aware of the smell of smoke and something burning. She quickly roused Robert Hartley from his recent slumbers.

The only matches in the house were in the couple’s bedroom and the manservant rushed upstairs whereupon John Garsden, fully awake but still in bed, told him where to find them. He urged the old farmer to follow him downstairs as a fire was suspected.

Opening the door of the front parlour Robert Hartley saw that the fire was raging in the room around a set of drawers. He went to fetch water and tried to douse the flames but it was hopeless and, as he looked on despairingly, the front windows of the parlour burst violently open. The oxygen from the chill outside air fuelled the already established fire turning it into an inferno. Hartley was forced to retreat out of the front door as the leaping flames ushered him back along the narrow corridor.

Whilst the manservant was tackling the conflagration Mrs Garsden had gone upstairs to look to John. By the time they were ready to descend the flames and smoke had cut off their escape route. Mrs Garsden tottered back into a lumber room losing contact with her husband who, coughing and hardly able to snatch a breath, retreated back to the couple’s bedroom…

Neighbours arrived on the scene and tried their best to assist the Oswaldtwistle Local Board fire brigade in their efforts to subdue the flames and rescue Mr and Mrs Garsden. A ladder was put up to their bedroom window. The body of the old man was found beneath the window in a kneeling position. His wife, lying with her face to the floor, was found insensible in the lumber room and carried to a nearby house. Despite great difficulty breathing, Mrs Garsden came round after two hours or so with the aid of Doctor Booth who had been called to attend and seemed to have succeeded in saving her life against all the odds. However, an unkind fate saw the old lady die at 10.30 pm the following evening.

Alice Tomlinson who was the daughter of Mr and Mrs Garsden had found her mother in the lumber room after risking her own life to search upstairs at the time of the fire. She had sinister and alarming news that sometime ago her father had been robbed by a man who, before going to prison for the offence, had threatened to burn the old man to death when he came out. A juryman thought this man had been released in October 1879 after serving twelve months but there was other evidence that he had been released only the previous week.

The Brown Cow inn at Duckworth Hall, Oswaldtwistle, scene of two deaths in February 1880. The author

The identity of the mystery man who had threatened elderly John Garsden was not known and, apparently, police enquiries all came to nothing. If, somehow, he had got into the front parlour of The Brown Cow on the fatal evening of the fire and was responsible for starting it then he achieved his object stealthily and silently some time after 9 pm when Robert Hartley had visited to wind the clock. Then again, carelessness with a candle on the part of the manservant or one of the Garsdens could have been responsible for the conflagration.

Certainly, the death of John Garsden and his wife aroused rumour and suspicion in the neighbourhood at the time. The inquest jury, however, had no option given the circumstances but to record verdicts of ‘accidental death’ in both cases. Had someone got away with murder?

A curious case occurred in November 1929 at Pleasington, near Blackburn. No one truly knows to this day whether farmer Roger Haydock, forty-five years-old, of Old Hall Farm, Pleasington, took his own life or was the victim of a grotesque and bizarre accident. The only witness to the tragic events was the farmer’s collie dog so the circumstances of his death will remain forever an obscure mystery.

Roger Haydock was a married man dedicated to his way of life and the land. On the morning of the incident he’d been cleaning the shippens in the stable at Old Hall Farm. He did not turn up for dinner at midday but his wife was not unduly alarmed and assumed her husband had gone to visit some other nearby farm on business. However, when he had not returned by 5.30 pm she began to worry.

In answer to a whistle, Roger Haydock’s collie dog, which invariably accompanied him, came down the pasture field adjoining the farm buildings alone. James Hindle Hartley, a labourer at the farm, followed the dog as it turned back in the direction it had come. The collie led him eventually to the far side of the pasture field where he found Roger Haydock lying on his back with a gunshot wound in the left breast. The farmer’s waistcoat was open and there were bloodstains on his shirt. A double-barrelled shotgun was suspended on a piece of wire fencing nearby, the wire being between the triggers. The dead man was lying with his feet some thirty-one inches from the fence facing towards the muzzle of the gun and it seemed like he had fallen backwards.

Police Sergeant Thompson attended and later gave evidence at the inquest. He stated that the stock of the gun was in the adjoining field and the muzzle, as described, facing towards Roger Haydock. There was a spent cartridge in the left-hand barrel whilst the right-hand barrel was empty. He noted, somewhat eccentrically, that the farmer was still wearing his cap.

The facts seem to point to a one-in-a-million accident in the affair. Roger Haydock had no doubt been negotiating the wire fence, the top strands of which had been broken, when his gun had caught in the loose wire. Attempting to extricate it, whilst perhaps unbalanced himself, he had inadvertently pulled the trigger and shot himself. No one but the dog knows.

It was said at the inquest that the farmer had ‘no worries’ and therefore no apparent reason to commit suicide so his death would seem to have been an accident. But do any of us really have ‘no worries’? People, when disturbed or depressed, sometimes subdue their real feelings in public very successfully whilst behaving oddly when alone. Roger Haydock’s strange demise will forever have a question mark hanging over it.

Unlike the uncertain end of Roger Haydock the death of Mrs Margaret Pusey Dugdale of Dutton Manor, near Blackburn, was clearly a case of suicide. The urge to put an end to oneself is no respecter of age, wealth, position or circumstances though undoubtedly more prevalent amongst the poor and down-trodden than the titled and diamond-tiaraed. In Mrs Dugdale’s case it is the stated reason behind the ultimate irrational act that intrigues and, perhaps, bemuses.

On Thursday, 7 February 1918, Mrs Dugdale’s husband Adam, a JP, left their home about 9 am to sit on the bench at Blackburn County Police Court. He left his wife in good health and had no misgivings regarding her condition or welfare.

Around noon Mrs Dugdale ventured outdoors. She requested their butler, Edward Bruford, to tell Bailey the gardener to join her up the field to help look for snares. Mrs Dugdale had not been gone long when Infelice Lacey, another gardener at the Manor, went into the house and came across a note from the JP’s wife. It asked the finder to send someone to look for her if she had not returned home by 1.30 pm.

A puzzled Infelice Lacey went about her work and waited till the appointed time when there was still no sign of Mrs Dugdale. Uneasy about the situation Miss Lacey went to look for the missing woman herself. She found her lying in a field opposite the nearby wood.

Hurrying back to the Manor, she telephoned for Doctor Patchett who arrived and pronounced Margaret Dugdale dead. The police, in the form of Police Sergeant Bannister, were soon on the scene. Where the body lay he found a mirror hanging on the top of a fence, a wooden mallet on the ground and, in Margaret Dugdale’s left hand, a humane cattle killer containing a discharged cartridge.

In a basket on the ground was a fully-loaded revolver and pinned to the basket were instructions for disposing of the body. Examining the corpse, Bannister saw the expected large puncture wound in the centre of the forehead where the lethal bolt of the humane killer had grievously penetrated. Clearly, with the loaded revolver as back up, the JP’s wife had come fully prepared to end her life oblivious of that good advice ‘Your life is not your own – keep your hands off it!’

Investigations revealed that the dead woman had basically enjoyed good health save for attacks of rheumatism in the last three years which depressed her at times. However, in May of the previous year an event had occurred which she had never seemed to get over or come to terms with. Her dog, called Fritz, had had to be shot on account of its advanced age and obvious suffering. The fifteen years she had owned him had left an indelible mark on her and the dog’s demise affected her personality to the extent that she became much more withdrawn and reserved – something confirmed by the servants at the subsequent inquest.

Police Sergeant Bannister outlined to the coroner, Mr Haslewood, the probable sequence of events in the case. Appearances pointed to Mrs Dugdale having put the cattle killer to her forehead in front of the mirror and caused the discharge of the cartridge by striking the killer with the wooden mallet found at the scene close to the body. The location she chose to commit the dreadful act was apparently near to where the dog Fritz was buried.

It was at the conclusion of the inquest that the coroner revealed some letters had been left behind by Mrs Dugdale. Though they were not read out Mr Haslewood said they showed how acutely distressed she had become after the loss of her dog.

The coroner also made the very subjective observation that ‘Perhaps she was at a stage of life when women got peculiar ideas into their heads!’ It was a comment unlikely, even then, to endear him to the feminine half of the population. Nowadays, understandably, a public lynching via the assembled media would have awaited him.

The jury in the case of Margaret Pusey Dugdale returned a verdict that the deceased shot herself whilst of unsound mind. It was as well for the coroner, if he was right, that few women at a certain ‘stage of life’ had access to firearms in those days towards the end of the Great War. There would have been a dearth of elderly ladies still able to draw their pensions and an overabundance of cases for him to pontificate upon.

Elizabeth McCartney, eighteen, was the adopted daughter of Thomas Whalley of 17 Atlas Road, Darwen. She had been employed as a weaver at Messrs Catlow’s Olive Mill in the town for some seven years – up to noon on Wednesday, 12 June 1901, when she was summarily dismissed from her employment.

There had been no complaint about Elizabeth’s work and she had been paid what was a fair wage for the times of twenty-two shillings (£1.10) a week so her dismissal seemed on the face of it inexplicable. Its tragic outcome, however, was only too plainly apparent when the young girl was found dead in an outbuilding of 17 Atlas Road, at 5.30 pm on the day they had finished her at the mill.

Doctor Marsden who conducted the postmortem examination was of the opinion that Elizabeth had probably died from oxalic acid poisoning. Extensive police enquiries failed to determine where she had obtained the Schedule 2 poison which she had used to destroy herself.

Thomas Whalley, who had adopted Elizabeth, worked at the same Darwen Mill and his evidence at the inquest threw considerable light upon the affair. It became clear that Elizabeth McCartney had become another tragic victim of the practise of ‘driving’ in weaving sheds.

By way of explanation, there were three systems operating in some cotton mills that amounted to direct incentives for overlookers to ‘drive’ weavers. Firstly, every weaver’s wage was published and placed on the overlookers’ benches. Tacklers, who were paid by commission upon the wages of the weavers under them, therefore knew precisely what each weaver was drawing and formed their own opinions.

The slate system, where overlookers went round on a weekly basis with a slate and recorded the number of pieces woven by an individual weaver on the looms, meant tacklers could identify under-performers and ‘grumble at them in strong language!’ Many a mill girl dreaded the dire prospect each week. Weavers whose wages fell under the average found a circle round their name and earnings and knew only too well that if it happened a time or two more they would be ‘out the door!’ Some found things so intolerable that death seemed preferable to the wear and tear and tension of the sheds.

Paying overlookers by poundage simply allowed them to increase their own wages by squeezing that much more out of their work-people. Naturally enough, they endeavoured to do so.

All of the above were prevalent in the Blackburn and Hyndburn areas at the turn of the twentieth century but not so in the nearby Burnley and Pendle districts. The wretched demise and wasted life of Elizabeth McCartney at least brought the problem of driving to the fore locally and the Northern Counties Weavers’ Amalgamation resolved to campaign to abolish the publishing of wages, the slate system and paying overlookers by poundage on the weavers’ earnings.

In Elizabeth McCartney’s case it is clear that John West, the overlooker who discharged her and considered her efforts were not good enough for him, and Messrs Catlow Ltd had a deal to answer for. Indeed, the coroner at Elizabeth’s inquest said as much when he commented:

This is the worst case of driving in cotton mills I have ever come across and I come across a great many. I must say that morally, though perhaps not legally, I think this girl’s death lies on John West…and on the manager and the master of the Olive Mill.

The jury returned a verdict of ‘suicide whilst of unsound mind’. Driven to destruction by an oppressive system and the greed and callous indifference of those who ought to have known better seems nearer to the mark.