Since the 1500s, when Spanish explorers first came to the New World, Spain had ruled Mexico. By 1820, Mexico had spread down through Central America, up as far north as present-day Oregon, and all the way to the west coast of North America. It included a huge chunk of land called Texas that shared borders with Louisiana.

In 1821, Mexico won its independence. It no longer belonged to Spain. There was a new government with a constitution. The Mexican Constitution was based in part on the US Constitution and granted many of the same rights, including the right to elect members of the government and the right of the states to govern themselves.

Very quickly, English-speaking settlers from the southern United States—from Louisiana, Tennessee, and Alabama—came flooding into Texas. Buying land there was cheap—as low as four cents an acre. People in the United States were said to have caught “Texas fever.”

At first, Mexico didn’t mind the arrival of American settlers. The country needed more people to help defend it against frequent attacks from Native American tribes such as the Comanche and Apache. The Mexicans, however, had a few rules: The settlers from the United States had to become Catholic. They had to swear to be faithful to the country of Mexico. Also, slavery was not allowed in Mexico.

The trouble was that Texians, as these English-speaking settlers were called, didn’t like to follow rules. Some brought slaves along and intended to keep them. The settlers didn’t want to become Catholic. All they wanted was the chance to own land. There was plenty of that in Texas. So they made Mexico their home. They put down roots.

In time, some Texians came to think of themselves as citizens of Mexico. Some married Tejanos—native Spanish-speaking Mexicans—and had families.

In 1832, things changed. A Mexican general named Antonio López de Santa Anna grabbed control of the government. He had been a hero in Mexico’s war for independence against Spain. Now he tossed aside the Mexican Constitution. Santa Anna declared even “a hundred years to come my people will not be fit for liberty,” and made himself dictator. When he took control, several states rebelled—and Santa Anna used force to stop the rebellions and punish the states.

In Texas, both Texians and Tejanos were divided over what to do about Santa Anna. Some Texians, like Stephen F. Austin, favored Texas remaining part of Mexico. They hoped in time Santa Anna would become more reasonable and let go of power. Others, such as Sam Houston, wanted war. They thought Texas had to break free from Mexico and Santa Anna. They wanted independence.

In 1821, Moses Austin had a dream to bring his family and three hundred other settlers to Texas from Missouri. When Moses died, his son Stephen led the new settlers into Texas, where they started a settlement called San Felipe de Austin. Eventually Austin would bring fifteen hundred families into Texas. For a long time, Austin was loyal to the Mexican government. In 1833, worried about other Texians’ growing demands for Texas independence, he went to the government in Mexico City. He asked for Texas to become an independent state that would stay under Mexican rule. Not only was his request denied, but Austin was also arrested. Austin stayed in jail for twelve months. Then he was paroled, but not allowed to go home for another seven months. He left Mexico City a changed man. He said, “Every man in Texas is called to take up arms in defense of his country and his rights.” Today he is known as the Father of Texas. The city of Austin is named after him.

Trouble was brewing in many towns. In Gonzales it boiled over.

The early days in Gonzales had been tough. But by 1835, Gonzales had begun to prosper. There were two small hotels, two blacksmith shops, and several bars. A new schoolhouse was being built, and a man named Almeron Dickinson had opened a hat shop. Native American attacks were not as frequent. The town had even held its first fancy ball.

The citizens of Gonzales had not wanted a war for Texas independence. However, they resented the way they were treated by Santa Anna’s soldiers. The soldiers were lawless. They were bullies. One soldier beat up a man with the butt of his gun.

Sam Houston stood about six feet four inches tall. He cut quite a figure, especially when in the Native American or Mexican clothes that he liked to wear. He became a hero in the War of 1812 and later a lawyer. He served two terms in the US Congress before being elected governor of Tennessee in 1827. He first saw Texas in 1832 and fell in love with it. Houston struggled with drinking and drug problems throughout his life. The Cherokee, who considered him a friend, called him Oo-tse-tee Ar-dee-tah-skee, or “Big Drunk.”

Four days before the Alamo massacre, he signed the Texas Declaration of Independence. It said Texas was free from Mexico. After the territory won its independence, he was elected president of the Republic of Texas twice. When Texas became a state, he served from 1846 to 1859 as one of its senators, and after that as its governor. The city of Houston, Texas, is named after him.

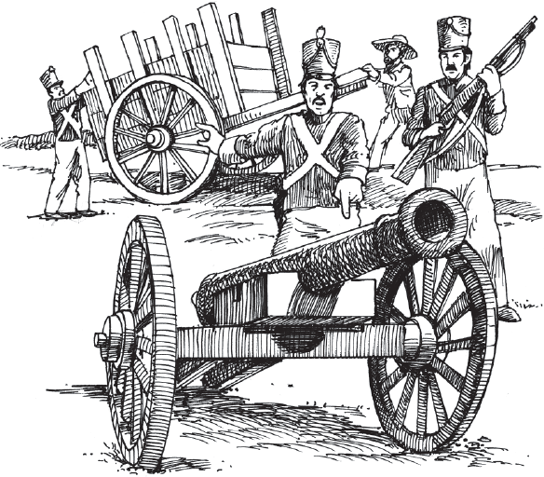

Then one day, more soldiers arrived with an empty oxcart. They demanded the town’s cannon. The message was clear: No one was allowed to have weapons except Santa Anna’s army.

It wasn’t much of a cannon. Just a six-pounder. That meant it shot small cannonballs weighing six pounds each. The cannon did little more than make a loud noise and belch smoke. However, the people of Gonzales refused to give up the cannon. They were taking a stand.

The soldiers rode away, but the townspeople knew they would be back. They sent out a call for help to other towns nearby. They needed more people to defend themselves against the soldiers.

When Santa Anna’s troops returned to Gonzales, about 140 men were ready to defend the cannon and the town. One young woman is said to have offered up her wedding dress to make into a flag. The flag showed a cannon and the words COME AND TAKE IT. This was like a dare to the soldiers.

Texian James C. Neill fired the first cannon shot. After a quick skirmish, Santa Anna’s soldiers retreated. The fighting at Gonzales wasn’t even a real battle. It was all over so quickly. Yet this day—October 2, 1835—was the beginning of the war for Texas independence.