The rebels fighting for freedom called themselves the Army of the People. They were all volunteers and elected Stephen F. Austin as their leader. By now Austin had changed his mind about war. Why?

In 1834, Austin was thrown in jail. All he had done was ask if Texas could become more independent. The answer was no. Austin then wrote a letter to warn his fellow Texians about the Mexican government’s hostility, and for that he was imprisoned.

The Army of the People under Austin marched from Gonzales toward the town of San Antonio de Béxar, or Béxar for short. (Today it is known as the city of San Antonio.) In Béxar, the rebel army planned to face off against Santa Anna’s troops stationed there.

At that point the army included about three hundred men: a ragtag bunch of farmers, shopkeepers, and craftsmen. They hoped to pick up more volunteers on the way. Few had military training. They had no uniforms—they wore buckskin breeches, shoes or moccasins, sombreros, top hats, or coonskin caps. They rode American horses and Spanish ponies, mustangs and mules.

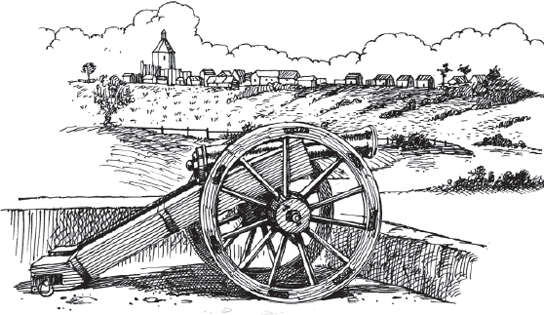

On October 27, 1835, the army arrived outside Béxar. Many thought it was the prettiest spot in Texas they’d ever seen. About sixteen hundred people lived there, mostly Tejanos. The bell tower of the Church of San Fernando rose up between the two town squares. Beyond the town center were mud and stick shacks, and then cornfields. To the east, across the San Antonio River, was the Alamo. About 650 Mexican soldiers were stationed there and in the town. Their leader was General Martín Perfecto de Cós. He was Santa Anna’s brother-in-law.

Inside the Alamo, the soldiers had built a ramp and a platform on what was left of the dome of the Alamo church. They placed cannons there that could fire over the church itself. They had also blocked off streets and set up five cannons in the town squares.

The Army of the People didn’t plan on attacking Béxar. That did not seem possible. Instead, Austin and his men settled in for a siege. A siege is when forces surround an enemy and wait them out.

In time the enemy’s food and supplies will run out and they will have to surrender. For weeks the Army of the People waited, growing more and more undisciplined. Many lost patience and went home to their families. They were replaced, however, by new arrivals from the United States eager to fight and to win themselves land in Texas.

Winter arrived, bringing cold weather and sickness. Stephen F. Austin, who was among the sick, had to travel to the United States to ask for money for the Texian rebels. That left the Army of the People without the popular Austin as leader.

By December, it seemed as if the siege would be called off. Then Texian rebel Ben Milam rode to Béxar. Originally from Kentucky, he’d been a US soldier. He’d fought in the War of 1812, and he was ready to fight again. Milam galloped up to the men and shouted, “Who will go with old Ben Milam” and fight? Milam was just the kind of man the rebel soldiers needed to fire them up. About three hundred men in the army rushed to join him.

At five o’clock in the morning on December 5, 1835, the battle in Béxar began. Milam’s men ran through the cornfields into Béxar. The Mexican artillery opened fire with clouds of grapeshot (clusters of small iron balls). The Mexican soldiers were in uniform and looked like a real army. But most of the soldiers had a gun called the Brown Bess. It was heavy, took a long time to reload, and wasn’t accurate. The Mexican gunpowder was often so weak that musket balls sometimes just bounced off the Texians.

The Brown Bess was no match for the Texians’ long rifles and double-barreled shotguns, which were easier to fire and more accurate. The long rifle also had a much longer range—as far as two hundred yards, twice as long as the Brown Bess’s one hundred yards.

In Béxar, the rebel army moved from house to house. About 135 Tejanos also joined in the fight. In some homes, the rebels only found scared Béxar residents who fled in their pajamas. But in some buildings they found Mexican soldiers. Then fighting would break out with pistols and knives and sometimes bare fists.

The fighting went on for five days. Both sides were exhausted. Ben Milam was killed. About three hundred Mexican soldiers had deserted. General Cós ordered all his remaining troops inside the Alamo. That was a mistake. There was no food or water and no way to defend the fort for any length of time. Cós was ready to surrender.

So the general and his men left on December 15, 1835. The Texians allowed them to keep some of their guns and ammunition, and even gave them a cannon. That way the Mexicans could defend against Native American attacks on the way home.

The Army of the People had won Béxar. The Alamo was theirs. Only five rebels had been killed; about 150 Mexican troops were dead. The rebels were sure they’d seen the last of the Mexican army until spring at least.

They were wrong.