The formation of a translation market is tied to the emergence, beginning in the seventeenth century, of intellectual production in vernacular languages and to the correlative development of the book market.1 The process of cultural construction of national identities that began at the end of the eighteenth century and the industrialization of print production beginning in the early nineteenth century led to the development of national markets, concentrated around a few cities such as Paris, Leipzig, London, and to the rapid expansion of translation.2 Translations, like exportations, circulate principally from the center toward the periphery.3 This asymmetry does not simply reflect the size of the markets. Political and cultural factors take part in structuring the circulation space for written texts, as, for example, in the competition among nations for cultural hegemony or in the symbolic capital accrued in a literary or scientific domain.4 Translation is, in fact, mediated by agents, both individual and institutional: translators, publishers, critics, booksellers, literary agents, and representatives of state agencies. For these agents, translation can fulfill various functions in the economic, political, and cultural realms. In addition to the formation of national identities and the development of the book market, two factors contributed to the appearance of specialized agents: immigration and the teaching of languages.

Among the books that are translated, literature occupies the primary position. Because of the role it has played in the construction of national identities, notably through the codification of the language and the formation of a canon, the translated literature market is also the one in which intercultural exchanges are the most diversified. As in the case of literary publishing, literary translations are subject to political and economic constraints, against which relative autonomy has been achieved since the nineteenth century.5

In that period, French literature occupied a dominant position in the world system of translation. That position began to decline after World War II, and especially starting in the late 1970s when the era of globalization began, marked by the increased domination of English.

The Nationalization of Literature and the Formation of a Translation Market

French literature long occupied a hegemonic position in the world republic of letters.6 A vernacular language that, like Italian, had already given rise to a few written works in the late Middle Ages when Latin reigned as lingua franca for scholarly Europe, French acquired a double political and literary legitimacy in the French kingdom in the sixteenth century with the 1539 Villers-Cotterêt edict that made it the official administrative and legal language, and with du Bellay’s La deffence et illustration de la langue françoyse, ten years later, which argued for its enrichment against the domination of Latin. This period saw the expansion of translations of ancient works. In the seventeenth century, the monarchial policy of linguistic unification throughout the realm raised French to the status of national language, delegating the role of codifying it to the Académie Française. That was the moment of the “birth of the writer.”7 The power of the absolute monarchy, its policy of supporting literary and artistic production that would guarantee its influence in the courts of Europe, and the development of the book market within the realm all contributed to making French the language of culture among the European elite in the eighteenth century.8

It was to counter the domination of French that national literatures in vernacular languages developed beginning in the late eighteenth century, from Scotland through Germany to Italy.9 The movement was led by the intellectual bourgeoisie (the Bildungsbürgertum in Germany), which pitted against the aristocratic European court culture national traditions created for that purpose.10 It was embraced in France during the Revolution, which laid the foundations for a national secular culture, and then with De l’Allemagne by Madame de Staël, published at the time of the empire’s collapse. The creation of university chairs in foreign literatures in 1830 instituted the “paradigm of the foreigner” that would henceforth structure the perception of translated literature as representative of a national culture, removing literature from the universal.11 It was only from that time on, and in direct relationship to these “foreign literatures” that the notion of “French literature” developed, according to a principle of division that would be transposed from higher education to publishing, with the appearance, beginning in the late nineteenth century, of series of foreign literature distinct from French literature, such as Stock’s “Bibliothèque cosmopolite.”

The nationalization and vernacularization movement in literature was linked directly to the industrialization of publishing, and to the spread of literacy and education. Translation, which became by 1850 the main mode of circulation for texts within the emerging international book market, played a major role in the formation of the national literary fields.12 It functioned to establish a core of works, a literary canon in the vernacular language, to make the vernacular language into a national language, and to provide writing models for emerging literatures.13 Whereas Balzac had been read in his time in French throughout Europe, the international circulation of Zola’s work occurred more through translation, which allowed it to reach a readership beyond the cultural elite who mastered French. At that time, French literature enjoyed unequalled prestige, from Russia to Latin America. In 1867, the Italian publisher Treves launched a literature series meant for a broad audience, which, until 1916, included translations of 136 French works (among them Balzac, Flaubert, Maupassant, Anatole France, Zola, and Bourget), as compared to seventy-five English, forty-four German, and thirty-four Russian works.14 Originating in England but spreading into southern Europe via France, the serial novel, appearing first as installments in periodicals, was the vehicle for popularizing literature in Italy as in Spain.15

In the second half of the nineteenth century, intercultural exchanges became increasingly structured by the nation-states that attempted to control the expanding book market. The Berne Convention, adopted in 1885 at the initiative of the Société des Gens de Lettres and taking up again the 1793 French legislation on literary property, was the first attempt at international regulation of this market to curb unauthorized editions. The French organizational model for the world of letters, with its professional associations (Société des Auteurs Dramatiques, Société des Gens de Lettres), spread into other countries as well.16

But France found its position weakened by its defeat to Germany in 1870, the consequences of which indelibly marked the collective consciousness. Under the Third Republic, these consequences favored the emergence of a nationalism that took the place of religion, increasingly privatized in the areas of morality and education until the separation of church and state in 1905. Literature was assigned the mission of education and illustration for the national culture. In the face of the republican conception of the nation, arising from a mix of northern and southern cultures and integrating all the denominational communities (Catholic, Protestant, Jewish) on the basis of the principle of voluntary inclusion and secularism, there emerged a nationalism along the German model, based on “race” (in the old sense of a community considered as a lineage) and blood; these two competing conceptions were refracted in the literary field.

The popularity that the Russian novel and Scandinavian literature enjoyed in France in the late nineteenth century, and the subversive uses to which some of the Symbolists put them, led in effect to a xenophobic reaction among certain French writers, which was not unrelated to the position they took in the Dreyfus Affair and to their investment in the development of a reactionary nationalism, embodied by the monarchist league Action Française, founded in 1904.17 In addition, Paris had become one of the places of choice for the literary and political avant-gardes (Russian and Italian futurism, for example) and a haven for political refugees. Moreover, the creation of the Republican University in 1896, which introduced true degree programs in letters and sciences, made the city a draw for foreign students, whose numbers multiplied in this period.18 Many of these immigrants subsequently became intermediaries between France and their culture of origin or other cultures, helping to renew the options in the French literary field and to increase the number of translated languages.19 French would become the language of choice for some of them, from Samuel Beckett to, more recently, Milan Kundera, through and including Eugène Ionesco, to name only the best known, who, in return, were annexed to French literature.

Directly following World War I, the policy of pacification promoted the internationalization of the world of letters. Thus the primary objective behind the 1921 creation of the PEN Club was to bring together writers devoted to peace and freedom to defend intellectual values against nationalism. Prompted by Philippe Berthelot, secretary general of the French Ministry of Foreign Affairs, a number of French writers, among them Anatole France, André Gide, Paul Valéry, and Jules Romains, joined their English counterparts. Exporting French books abroad became one of the missions of French foreign policy. The creation of the League of Nations in 1924, and the establishment of its own commission for intellectual cooperation undoubtedly helped to intensify such exchanges.

Embedded within the book market and interest-based relations, international literary exchanges were promoted especially by actors in the literary field who occupied key positions in publishing and official proceedings, and who managed to preserve a certain autonomy for these exchanges with respect to economic and political constraints. In France, in periodicals such as La Nouvelle Revue Française, founded by André Gide and published by Gallimard, and Europe, published by Éditions Rieder with Romain Rolland as its patron, an intercultural dialogue opened thanks to the contributors’ linguistic skills and international networks, not without incurring virulent attacks from the nationalist populist camp.

In the 1930s, the number of titles translated into French increased significantly, from 430 in 1929 (which represented 3.8 percent of all the books published that year) to more than one thousand in 1938 (13 percent of books published).20 More than half the translations were literary works. Among the source languages, English had the highest share (increasing from one-third to almost one-half), followed by German, Russian, Italian, and Spanish. In 1931, Gallimard created its Du Monde Entier series, which would become one of the most important series of foreign literature (in 1972, it could boast of 320 authors, sixteen of them Nobel laureates, representing thirty-five countries). It was in this period that Gallimard began to introduce France to American literature, one of the sources for developing new narrative techniques. We know that Sartre drew inspiration from the novels of Dos Passos and Faulkner for La nausée (published in 1938, translated into English as Nausea). He also declared obsolete the device of the omniscient narrator, to be superseded by internal focalization of the narrative (adopting the characters’ points of view). Another source for revitalizing fiction techniques, Kafka’s The Castle, appeared in French from Gallimard in 1938.

Unlike French publishing, American publishers did not have staff specializing in translations, which made intermediaries necessary. The Bradley Literary Agency performed that function in the interwar period. This was the agency that sold the rights for Faulkner, Dos Passos, and Steinbeck to Gallimard. In exchange, Gallimard entrusted Mrs. Bradley with representing its rights in the United States. By that time, the era of bestsellers had begun. In 1939, a French translation of Gone with the Wind sold more than 800,000 copies.

Until that moment, French literature had played a central role in the formation of an international canon, along with English and German literature. Five French writers numbered among the canonized authors most translated throughout the world: Alexandre Dumas, Honoré de Balzac, André Maurois, Georges Simenon, and Jules Verne.21 French literature was by far the most translated literature into Italian, for example, representing an average of 133 titles per year between 1923 and 1928 (nearly 60 percent of which were fiction), as compared to twenty-nine from English (a third of them fiction) and sixteen from German (very few of them fiction). But beginning in the late 1920s, French lost its hegemony in Italy: the number of literary translations from other languages, German and English in particular, increased significantly.22

World War II interrupted the internationalization movement. The number of translations into French fell to 119 in 1941 (compared to more than one thousand in 1938, as stated earlier). The German cultural policy in occupied France was aimed explicitly at shattering French cultural hegemony. Regulating the flow of translations was one of the cornerstones of this policy. Thus, only eleven French authors were authorized to be translated into German.23 The titles that were translated served an overtly political objective. The majority of them dealt with the war and France’s defeat. Only two books of fiction were translated, Monsieur des Lourdines by Alphonse de Châteaubriant and Manon by Jean de La Varende, novels that, beyond rewarding the authors for their fidelity to the occupying power, were meant to illustrate France’s agricultural vocation in a Europe unified under the aegis of Nazi Germany. At the same time, translations from German rose in this period, accounting for one-third of all translations into French (113 out of the 322 appearing in 1942).

On the other hand, intellectuals exiled to the United States contributed to making French literature better known there.24 In 1942, Jacques Schiffrin, the founder of the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, became partners with Kurt Wolff, Kafka’s publisher, who had founded Pantheon Books, and published Resistance writers such as Gide, Aragon, and Vercors. After the war, this publishing house became one of the major importers of French and German literature to the United States.

Exchanges and Struggles for Hegemony Between France and the United States

The second half of the twentieth century marked a new era that saw the world book market become progressively freer and more unified. American hegemony gradually came to assert itself over this market, while French hegemony declined.25 This process was part of a wider movement toward free economic exchanges between states, initiated by the United States within the framework of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), signed in 1947. In 1946, the Blum-Byrnes agreements had already opened the French market to American cultural products.

From 1949, when French publishing regained its prewar production rate, until 1958, translations represented about 10 percent of the books published in French, that is, an average of 1,023 books per year for the decade, which placed France third among translating countries.26 A few translations appeared on the best-seller list published in 1955 by Les nouvelles littéraires. Le petit monde de don Camillo by Giovannino Guareschi, translated from Italian in 1951 by Éditions du Seuil, claimed a big lead with 798,000 copies sold by 1955. The success of some best-sellers, such as J’ai choisi la liberté (I Chose Freedom) by Victor Kravchenko (503,000 copies) and Le zéro et l’infini (Darkness at Noon) by Arthur Koestler (450,000 copies), was directly related to the political climate of the Cold War. In 1957, Le journal d’Anne Frank had only sold 30,000 copies, but by 1970, it had sold 800,000.27 Even though translations into French represented thirty languages, as early as 1946 more than half the books translated were from English, and that share peaked at two-thirds in 1949. With a decade average of 224 titles per year until 1958, books translated from American English represented 28 percent of translations into French, ahead of translations from German (137), Italian (55), and Russian (47). If the success of an author such as Hemingway (translations of For Whom the Bell Tolls and The Old Man and the Sea sold more than 200,000 copies by 1955) and Boris Vian’s decision to publish four of his novels under the pseudonym of Vernon Sullivan (the first was J’irai cracher sur vos tombes, appearing in 1946) attest to the prestige that American literature had acquired, the arrival of mass market literature, for which Kathleen Winsor’s novel, Forever Amber became the symbol, provoked opposition on the part of the Gaullist right as well as the Communist left against what was perceived as economic imperialism. Beginning in 1948, the policy of promoting French literature abroad was reorganized around two principles: defending the French language worldwide and promoting French culture, for which the book was considered one of the most important vectors.

In the 1950s, Paris remained a place that drew writers from all countries. Henry Miller, Richard Wright, James Baldwin, and Chester Himes found a kind of freedom there that the United States did not offer them. A number of authors fleeing the Communist regimes of Eastern Europe settled in Paris, while newly established legal and illegal translation circuits permitted the importation and very politicized reception of works by authors who stayed behind and by the generations that succeeded them, from Boris Pasternak to Witold Gombrowicz.28

According to UNESCO’s Index Translationum, books translated from French then represented more than 10 percent of all translations worldwide. The new trends in postwar French literature, existentialism followed by the nouveau roman, enjoyed worldwide distribution, thanks to strategies developed by a new generation of French publishers and the professionalization of intermediaries, such as Japan’s French copyrights office, founded in 1952. In the United States, they were introduced thanks to very committed mediators such as Jacques Schiffrin and then his son André, who in 1962 became the head of Pantheon Books, where he published Foucault, Sartre, and Duras;29 Richard Seaver, who published William Burroughs, Henry Miller, and the Beat Generation at Grove Press, and who introduced Beckett, Ionesco, and Genet to American readers; and the literary agent George Borchardt, whose career we will trace briefly.

Originally French, Borchardt came to the United States at nineteen to learn English and, through a New York Times want ad, first found a position at the Bradley Literary Agency, which had sold the rights to Albert Camus’s L’étranger (The Stranger) after World War II for an advance of $350. George Borchardt was quickly encouraged to start his own agency by Paul Flamand, founder of Éditions du Seuil, a publishing house that opened before the war. Flamand was beginning to diversify his catalogue and promised to let Borchardt represent his titles. Borchardt also obtained the rights to General de Gaulle’s Mémoires de guerre, published by Plon, and the exclusive right to represent Éditions de Minuit, another young publishing house, established clandestinely during the war and becoming the home of innovative postwar literature by publishing the works of Samuel Beckett and the nouveau roman. That was how George Borchardt introduced the French avant-garde to the United States in the 1950s. He acted as the agent for all of Sartre’s works, beginning with Les mots (1964, published in translation the same year by G. Braziller), and also sold titles by Eugene Ionesco, Beckett, and Marguerite Duras, as well as Histoire d’O (1954, translated the same year by Olympia Press). When he first tried to place Beckett’s books, he received letters calling the prose unreadable and the author a pale imitation of Joyce. He finally turned up a small publisher, Grove Press, that agreed to pay two hundred dollars in advance for En attendant Godot, as part of a larger thousand-dollar deal for three books: Molloy, Malone meurt, and En attendant Godot. When he offered Elie Wiesel’s La nuit to Blanche Knopf, she told him he was wasting his time, that this author would never find a readership in the United States. Nevertheless, the book was published in English in 1960 and became the biggest best-seller for translations in the United States: more than ten million copies have been sold (including three million of the new translation by Marion Wiesel, published in 2006).

Borchardt did not limit his catalogue to literature. He also focused on the human sciences, coming into their own in France in the 1960s. After Tristes tropiques by Claude Lévi-Strauss, which appeared in translation in 1961 from Criterion Books, and Les damnés de la terre (The Wretched of the Earth) by Frantz Fanon, translated by Grove Press in 1963, he represented Barthes’s work for Seuil and Foucault’s work for Gallimard. Borchardt’s agency was thus responsible for more than two thousand French book translations in the United States. It contributed to the “French Theory” trend that began in the 1960s and would lead to the deconstruction of the literary canon.30

In this period, publishing experienced unprecedented growth worldwide. Between 1955 and 1978, the number of books published in France, Germany, and Japan tripled (from 10,364 in 1957 to 31,673 in 1977 for France);31 it multiplied six times in the United States (from 12,589 to 85,126 titles). In 1974, the publisher Robert Laffont remarked, “Paris is only one stop now in the circuit of literary capitals, of which New York has become the center.”32

This growth in American production reinforced the supercentral position of English in the world system of translation. At the end of the 1970s, 45 percent of translations worldwide came from English, while other central languages, German, French, and Russian, represented between 10 and 12 percent according to the Index Translationum. Eight languages, including Spanish and Italian, occupied a semi-peripheral position, representing from 1 to 3 percent. With a share of less than 1 percent in the international market, all the other languages occupied a peripheral position.33

Regarding the number of copies of translations in circulation, the distribution was even more unequal. Henceforth production in English would have something of a monopoly on mass-market books, best-sellers, popular literature, romances, and thrillers. While popular literature was not insignificant in translations from French in the 1960s, the latter became concentrated around “upmarket” literary products and around the social and human sciences, with the success of “French Theory,” whose global diffusion was mediated by its reception in the United States.

The Position of French in the World Translation Market in the Era of Globalization

This evolution coincided with changes in the publishing world, notably concentration and internationalization, favored by the neoliberal turn of the 1970s, which saw the abandonment of the theme of development in favor of globalization, with a view toward opening borders to the free circulation of goods and capital. A global book market developed, with its own proceedings, such as the international book fairs (each cultural city henceforth hosts one, from Peking to Ouagadougou to Guadalajara), and professionalized actors: representatives for foreign rights in publishing houses, literary agents, specialized translators.

The rise in translations is an indicator of the intensification of exchanges in this new period: between 1980 and 2000, the number of books translated worldwide went from 50,000 to nearly 75,000 (including new editions and reprints) according to UNESCO’s Index Translationum—that is, an increase of 50 percent. The annual average of translated books increased by 20 percent between the 1980s and the 1990s. This intensification was accompanied by a diversification of exchanges, as evidenced by the appearance of languages rarely present in the translation market in the past, notably Asian languages, but also by the growing domination of English. Its share rose to 59 percent of translations in the 1990s, while Russian’s fell from 11.5 percent in 1980 to 2.5 percent after the collapse of the Berlin wall. German and French maintained their positions, representing 9 percent and 10 percent of the total, respectively.34

In this configuration, French remained the second central language. Its place in the global translation market can be estimated according to several indicators. First, the share of translations from French into other languages; second, the share of translations into French among all the books translated worldwide; third, the relationship between the number of translations from French and into French. Analysis is based on the data provided by the Index Translationum on the number of books in translation published every year, and by the Syndicat National de l’Édition on the number of contracts signed annually by French publishers to acquire or grant translations rights.35

The first language translated in the United States and the United Kingdom (followed very closely by German), French places second after English in many countries in terms of titles translated. According to Index Translationum statistics, that is especially true in Romance-language countries such as Italy, Spain, Brazil, Argentina, and Romania, as well as Arab countries and Israel. On the other hand, in the Netherlands, Sweden, and, since 1989, in most of Eastern Europe (Poland, Hungary, Czechoslovakia), French follows in the third position after English and German. French and German are closely tied in Japan and Korea (where their share is ten times less than that of English).

After a decline in the mid-1990s, the number of translations of books from French into other languages reestablished its ascending curve. Though it has lost its hegemony to the supercentrality of English, French seems to have regained its centrality as compared to languages other than English in the world system of translation by strengthening its position in Europe (translations into Spanish, Italian, and German, the first languages translated from French in the European market, seem to have increased) and by conquering the Asian market. Although incomplete, the data from the Syndicat National de l’Édition, on the number of contracts granted by French publishers for the translation of books into various languages, provides an idea of the present situation: among languages translating from French, Romance languages come first, ahead of English and German, which were also outstripped by Korean and Chinese between 2001 and 2005 (see table 19.1).

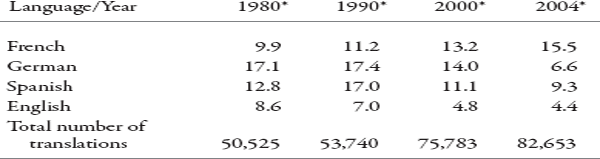

On the other side, French is one of the three languages (with German and Spanish) into which the highest number of books was translated in terms of absolute numbers. In 2004, it achieved first place. After a decline in the mid-1980s, the share of books translated into French in the global market increased steadily, from close to 10 percent in 1980 to 13 percent in 2000, and then to 15.5 percent in 2004, while the shares of books translated into German and into English declined (see table 19.2).36

In fact, the growth in translations into French was two times higher than the international average: the annual number of translations into French, including new editions and reprints, doubled between 1980 and 2000, according to Index Translationum data, going from five thousand to about ten thousand, to reach nearly thirteen thousand in 2004. About three-quarters of those translations appeared in France. Translations produced in Quebec doubled as well, going from 346 in 1980 to 862 in 2000 (and to 865 in 2004). The same evolution occurred in Belgium, but more slowly, with 200 books translated in 1980, growing to 426 in 2004, while Switzerland remained stagnant at around 250. In the countries of the Maghreb, where a certain number of houses were publishing in French, translations from Arabic into French began to increase. In contrast, there was only a single title translated (from English) into French in the Ivory Coast in 2004, Vandana Shiva’s Protect or Plunder? Understanding Intellectual Property Rights, from the publisher Éburnie in Abidjan (there were no titles in other African francophone countries, but that may be a problem with the data).

TABLE 19.1 Languages with the highest number of contracts for translations from French (in decreasing order)

1996 – 2000 |

2001 – 2005 |

|

Spanish |

Spanish |

Italian |

Italian |

Portuguese |

Portuguese |

English |

Korean |

German |

Chinese |

Korean |

English |

Greek |

German |

Japanese |

Greek |

Chinese |

Russian |

Romanian |

Japanese |

Dutch |

Romanian |

Polish |

Polish |

Turkish |

Dutch |

Russian |

Turkish |

Czech |

Czech |

Bulgarian |

Bulgarian |

Hungarian |

Serbian |

Catalan |

Hungarian |

Danish |

Catalan |

Arabic |

Arabic |

|

Source: Syndicat National de l’Édition.

TABLE 19.2 Changes in the share of translations into French, German, Spanish, and English in the global translation market

* Numbers are expressed as percentages.Source: Index Translationum.

With regard to France, this development in translation does not mechanically reflect the growth in the book market. In the first place, the share of translations in the national production increased appreciably, going from no more than 10 percent in the 1960s (fewer than two thousand titles) to 14 percent in 1970 and from 15 percent to 18 percent between 1985 and 1991 (which represents, in absolute figures, an increase of more than 50 percent in books translated per year, from about three thousand to forty-four hundred new titles).37 By comparison, it was 3.3 percent in Great Britain at that time, whereas it reached 25 percent in Italy,38 which confirms that the translation flow circulates mainly from the center toward the periphery. The rate of translations into French continued to increase before declining early in the second millennium: in 2005, it was at 15.9 percent, which still represents twice as many new translated titles as in the early 1990s.39

Conforming to the global trend, it was the number of translations from English into French that experienced the greatest increase in absolute numbers: they more than doubled. After English, German was the language most translated into French, but it seems to be outstripped by the late 1990s by Italian and indeed even by Japanese, if we consider the number of acquisition contracts signed by French publishers (see table 19.3). This strengthening of exchanges with Asian countries, already evident from contracts in the other direction, may seem paradoxical at a time when the European Union was forming. On the other hand, Eastern European countries’ entry into Europe and the development of publishing in those countries favored exchanges with Western Europe, following the apparent lack of interest immediately after the collapse of the Berlin Wall.40

TABLE 19.3 Languages with the highest number of contracts for translations into French (in decreasing order)

1997 – 2000 |

2001 – 2005 |

|

English |

English |

Italian |

Japanese |

German |

German |

Japanese |

Italian |

Spanish |

Spanish |

Dutch |

Dutch |

Chinese |

Chinese |

Portuguese |

Portuguese |

Swedish |

Russian |

Russian |

Swedish |

Arabic |

Greek |

Turkish |

Hebrew |

Hebrew |

Czech |

Norwegian |

Arabic |

Polish |

Hungarian |

Greek |

Polish |

Hungarian |

Romanian |

Czech |

Turkish |

Romanian |

Norwegian |

Source: Syndicat National de l’Édition.

The ratio of translation flows between French and the other central or semi-peripheral languages is an indication of its centrality. Not considering English, there were more titles translated from French into other languages than the reverse, which attests that it has kept a central and dominant position in the world system of translation. However, the ratio of translations from English into French and from French into English practically doubled during the period, which shows that the increase in the former was not matched in the other direction. On the other hand, in relation to German and Spanish, the ratio of translation flows declined, which confirms the earlier report of a relative weakening of the centrality of French in the 1990s, recouped at the beginning of the second millennium.41 In 2006, French publishing houses sold six times more titles for translation than they acquired.

French Literature or World Literature?

In this world system of translation, literature, on which we will focus in what follows, is the category of books most translated; it represents about half of all translations worldwide. Between 1980 and 2004, nearly 9.7 percent of literary translations produced worldwide were from French, but the share of literature translated from French declined in the global translation market from the beginning to the end of this period, falling to 7.7 percent in 2004, whereas the share of literature translated from English increased from one-half to two-thirds.

On the strength of its past prestige, French literature still boasts six of the fifteen most translated authors worldwide. Among the ten writers most translated from French are Jules Verne, Alexandre Dumas, Honoré de Balzac, Charles Perrault, Albert Camus, and Antoine de Saint-Exupéry—that is to say, authors of scholarly classics or children’s literature, in addition to three graphic fiction writers (René Goscinny, Hergé, and Albert Uderzo). From the perspective of total number of translated titles, however, contemporary “literary fiction” now prevails over the classics.

In the world of U.S. publishing and journalism (and in those countries most oriented toward the United States, such as Israel and the Netherlands), there is talk of the decline of French literature nevertheless.42 According to the publishers and literary agents whom I queried, this decline is primarily manifested in the demise of France’s sanctioning powers in the global republic of letters. In the past, the Prix Goncourt was sufficient for obtaining translation offers even before the winning book had been read, no doubt thanks to the international success of a few prizewinners that became best-sellers worldwide, namely Simone de Beauvoir’s Les Mandarins in 1954, André Schwartz-Bart’s Le dernier des justes in 1959, and Marguerite Duras’s L’amant in 1984. For about fifteen years now, however, the winning book has not even been mentioned in the New York Times. What is more, there were no best-sellers translated from French into English until Suite française by Irène Némirovsky, a story of the “exodus” of the French civilian population during the 1940 German invasion by a Jewish writer who died in deportation in 1942, though its success in the United States has helped to make French literature more visible. Despite high expectations, Les bienveillantes by Jonathan Littell, an American by birth who writes in French and who won the 2006 Prix Goncourt for this novel, which describes the horrors of World War II from the viewpoint of a Nazi officer, gained a mixed critical reception when it appeared in the United States as The Kindly Ones in 2009. Significantly, these two novels are set within the framework of World War II. The historical dimension constituted their main attraction. They distinguish themselves in this way from a kind of French writing criticized as self-absorbed by publishers who expect a work of fiction “to tell a good story.” Nevertheless, Jean-Philippe Toussaint’s La salle de bain was a true best-seller in Japan (it appeared in English in 2008 but has had a more limited reception in the Anglo-American world). Another best-seller in the United States was L’élégance du hérisson by Muriel Barbery. Is the opposition between Anglo-American literature’s knowing how “to tell stories” and French literature’s abstract formalism enough to explain these developments? That would suppose that “French literature” or “American literature” form a unified whole; whereas on the contrary, it is a matter of two markets structured by an opposition between large-scale distribution based on the criterion of short-term profitability, on one hand, and on the other, small-scale distribution projected over the long term according to the principle of accruing symbolic capital (building a “backlist”), where intellectual criteria prevail.43 These national markets are embedded within a global market, which is itself doubly structured by this same opposition, along with the already mentioned cleavage between center and periphery.44 If, at the pole of small-scale production, upmarket publishing in the United States has adopted the French model, the consecrating power in this global space has undeniably shifted, since the 1970s, at least in part from Paris to New York (although Paris still remains one of the centers of the world system of translation).

But the major change is that the large-scale distribution sector has increasingly imposed its profitability criteria on the small-scale distribution sector of the global book market. Because of its stability, publishing has become a coveted sector among large communication groups and others that have, in turn, imposed their model of short-term profitability over intellectual value.45 The rationalization process, through the integration of production and distribution, is disrupting this sector’s traditional economy where artisanal methods still prevail. Whereas traditional publishers have sought to balance the losses for more difficult books with a few successes, the shareholders of large groups increasingly demand that profitability be calculated per publication.

The effects of this process are most dramatic in the United States, where the greatest concentration of book distribution is through bookstore chains, as opposed to France, for instance, where a network of independent booksellers still exists. In a system of continual overproduction, books classified as upmarket find themselves having to compete with best-sellers and popular literature for access to sales outlets. The big chains, which privilege the mass market, can decide to “skip” this or that title, so that not a single copy of a book will be available in the chain’s twelve hundred stores. Furthermore, large communication groups purchase spots for their books in the bookstore windows or near the counters. And finally, the number of pages the press devotes to literary criticism tends to be diminishing, in the United States as in France and elsewhere, which further reduces the chances for upmarket literature to reach the public.

In the United States, these developments have negative consequences for translated literature.46 Little valued, translations are often not presented as such: the fact that the book is translated is not indicated on the cover. For all these reasons, upmarket contemporary literature translated from French finds itself increasingly confined to the non-profit sector in the United States, as illustrated by Dalkey Archive Press (Raymond Queneau, Michel Butor, Pierre Klossowski, Nathalie Sarraute, Jean Echenoz, Jacques Roubaud, Annie Ernaux), the New Press (Marguerite Duras, Claude Simon, Jean Echenoz, Patrick Chamoiseau, Marie Darrieussecq, Antoine Volodine), Archipelago Books (Pierre Michon), Open Letter (Mathias Enard), and a few small independent houses such as David R. Godine (Georges Perec, Patrick Modiano, the 2008 Nobel Prize winner Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio, Jean Echenoz, and Sylvie Germain), Green Integer (Olivier Cadiot, Jacques Roubaud, Andrée Chédid), Arcade (Amin Maalouf, Andrei Makine, Jean Rouaud), and Seven Stories (Annie Ernaux, Assia Djebar). But within the large groups, certain publishers with upmarket literary imprints also consider translation a means by which to combat the domination of English. One told me, “I think networking and word of mouth is very important for discovering books to translate from foreign languages. It is very important to do that in this country and into the English language in general because I do believe there is a kind of imperialism of the English language throughout the world and publishing translations is my way of combating that.”

Nevertheless, it is the best-sellers and mass market genres (romances and thrillers) that have contributed most to the increase in translations worldwide. If we consider the language of origin as an indicator, linguistic and cultural diversity is almost nonexistent at the mass-market end of publishing, where, as I have already suggested, English has a virtual monopoly. Conversely, diversity is higher in the small-scale distribution sector, which attempts to counter the economic imperialism of the mass market with an alternative form of globalization, based on the diversification of exchanges between cultures.

The publishing sector where linguistic diversity is greatest, literature is also the sector in which the rate of translations is generally highest: in France, at least one out of three works of fiction published in a given year is a translation, and if English dominates among fiction translations into French, it is relatively underrepresented in the small-scale production sector, to the profit of other languages.47 Indeed, in the foreign literature series of the great French publishing houses, such as Gallimard, Le Seuil, Fayard, and Albin Michel, we find works translated from twenty or thirty languages and from thirty or forty different countries. Moreover, the mediators for foreign literature have diversified in France since the late 1970s, with the creation of Actes Sud, which translates from thirty-six languages, and other small publishers such as Bourgois, Métailié, Corti, Verdier, La Différence, and Jacqueline Chambon, who have specialized in the translation of Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, German, as well as Eastern European languages (Éditions de l’Aube) and Asian languages (Picquier). Linguistic diversity has increased partly because government policies on state subsidized translation have expanded since the 1980s. One of the special features of the French policy is that funding is allocated not only for the translation of French into other languages, but also for works of contemporary literature and human or social sciences translated into French. Between 2003 and 2006, the Centre National du Livre, which is a branch of the Cultural Ministry, has awarded grants for works translated from more than thirty languages.

Accordingly, Paris retains consecrating power for the literature of semi-peripheral or peripheral languages, to which it grants access to the international scene. As in the past for the Russian writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the 1970 Nobel laureate in literature, the French translation served as a springboard for the Albanian author Ismaël Kadaré, the winner of the first Man Booker International Prize in 2005. The same was true in the early 1980s for Manuel Vásquez Montalbán, the Spanish innovative author of mystery novels. In these two cases, moreover, the works were subsequently translated from the French translations, which became the standard reference.

The central languages are mediators: a book has a better chance of being translated from a peripheral language into a central language or into another peripheral language if it has already been translated into a central language. Beyond the obvious consecrating factor that a previous translation represents for a work, the issue of linguistic competence also comes into play. Publishing houses in the United States generally have editors who know French and/or English, more rarely German, but for the other languages, competence is lacking. “French is my gateway language,” an American editor explained to me in reference to acquiring the rights for a Korean novel that she had read in the French translation. In this respect, French plays a role in maintaining cultural diversity in the global book market.

How to explain the gap between the large-scale and small-scale distribution sectors from the standpoint of linguistic diversity? The prevailing function of entertainment at the mass-market end is countered in various ways by literature’s didactic, identity-defining, or strictly aesthetic functions in the small-scale distribution sector. The identity-defining function can apply to a nation, region, or gender, to a social, religious, or ethnic group. Having played a central role in the construction of national identities, literature is still firmly rooted in these traditions in many countries, even if the international circulation of literary works, by way of translation especially, has permitted the formation of a relatively autonomous world republic of letters.48

Moreover, state involvement in cultural exchanges can reinforce the identification of a language with a nation or a country, to the detriment of regional and immigrant languages. This issue frequently provokes controversy during international book fairs or exhibitions. For example, at the 2008 Salon du Livre de Paris, where Israel was the featured guest, organizers were accused of having invited only authors writing in Hebrew, whereas Arabic is the second official language of the country, and works in Russian, English, and other languages are also published there—yet it should be noted that this phenomenon is not specific to Israel: in France and in other countries, there are also writers writing in other languages who are not included in the national culture. In 2007, the fifty-ninth Frankfurt Book Fair, where Catalonia was the featured guest, was boycotted by a number of writers because initially only authors writing in Catalan had been invited, whereas many authors residing in that region write in Castilian; the organizers were accused of favoring Catalan separatist nationalism.

Recognition on the national level has long constituted at least a necessary if not sufficient condition for access to the international scene. This has led to the exclusion of minorities and oppressed groups. The national canons were indeed constructed by those who held all the best assets for attaining literary success and consecration power, that is white men from families rooted for more than one generation in the national culture, established in the national cultural centers (or even just in the nation’s capital in a centralized country such as France), and with relatively abundant cultural capital at their disposal.49 The awarding to the black writer René Maran of the Prix Goncourt in 1920 provoked a general outcry in France. Not until after World War II was the Goncourt won by a woman, Elsa Triolet, Jewish and an immigrant from the Soviet Union, no less. That was in 1945, the same year that women obtained the right to vote in France. Marguerite Yourcenar was the first woman to enter the Académie Française, in 1982. If Charles Plisnier, a Belgian, won the Goncourt in 1937, writers from the former colonies had to wait until the 1980s to find consecration at the center of the francophone world, and it was often through a collective identity strategy—“women’s literature,” “negritude,” “francophonie”—that they managed to penetrate the literary and publishing fields, well before some of them achieved individual recognition through publication in collections of French literature.50 Léopold Sedar Senghor’s election to the Académie Française in 1983, and Assia Djebar’s in 2005; the Prix Goncourt awarded to Tahar Ben Jelloun in 1987, to Patrick Chamoiseau in 1992, to Amin Maalouf in 2006, and to Marie NDiaye in 2009; and the Prix Renaudot awarded to Ahmadou Kourouma in 2000 and Alain Mabanckou in 2006, all indicate a change.

An outcome of decolonization, this change is undoubtedly also the result of the growing incorporation of literary exchanges into the global market of translation and of the shift from Paris to New York as the center of literary consecration, which led to a transformation in the modes of access to the “universal.” The new awareness that engendered affirmative action policies and theories of deconstruction brought about the relativization of the national canons. This was conceptualized through the notion of “diversity.” Writers and especially women writers, immigrants, those from the former colonies, or racial “minorities,” garnered increasing attention from publishers, especially in the United States. From this perspective, the year 1992 marked a turning point, with the Nobel Prize going to Derek Walcott, the Booker Prize to Michael Ondaatje, and the Prix Goncourt to Patrick Chamoiseau. Toni Morrison won the Nobel Prize the following year. That same year, French book policy was redefined in order to include all French language authors, regardless of nationality. In 1993 as well, Michel Le Bris devoted issue number 11 of the journal Gulliver to “World Fiction,” a concept he imported from the United States. Fourteen years later, noting that the Goncourt, the Grand Prix du Roman de l’Académie Française, the Renaudot, the Femina, and the Goncourt des Lycéens had all gone to writers from “outside France,” Le Bris issued a manifesto, with the writer Jean Rouaud, affirming the emergence of a “world literature in French,” a notion that they oppose to the term “francophone.” Published in Le Monde on March 15, 2007, signed by forty-four writers, it gave rise to a work published by Gallimard that same year under the title Pour une littérature-monde. The manifesto was criticized for, under the pretext of defending the periphery against the center, promoting a traditional conception of fiction against a more innovative and experimental approach.51 It was certainly a strategy for adapting to the trends in the world market of translation, and especially in the Anglo-American book market.

Among the thirty or so contemporary French language writers most translated and reissued in English since the 1990s according to a database built by the French Bureau du Livre in New York (which is incomplete), one-third are women. With regard to origins, one-third of them are Québecois (they are mostly translated by Canadian English-language publishers), four are from former colonies or overseas territories (Tahar Ben Jelloun, Assia Djebar, Patrick Chamoiseau, and Maryse Condé), and two are immigrants (Andrei Makine and Marek Halter).

This development has been accompanied by a dissolution of the very notion of “French literature” in the Anglo-American market. It is significant that, among the authors translated from French, those who are not identified as such seem to garner the most interest from publishers, who sometimes go to great lengths, moreover, to conceal the source language, as in the case of Milan Kundera, the only French language writer on the shortlist for the first Man Booker International Prize in 2005. Similarly, the title of Andrei Makine’s book Testament français was translated as Dreams of My Russian Summers, thus obscuring the reference to France.

This seems to indicate a tendency toward denationalizing literary production in the world market of translation, which is largely a result of the ideology of globalization and the interest multinational companies have in abolishing cultural boundaries and national traditions to better impose worldwide best-sellers. It is reinforced within the small-scale distribution sector by the conception of “world literature,” and by the strategies of a new generation of writers concerned with ensuring in advance the translatability of their works.52

In France, this tendency should, logically, lead eventually to questioning the separation between “French literature” and “foreign literature(s)” that continues to organize higher education and upmarket publishing, and that would more accurately be designated as “literature in French” (which can include authors from other countries, for instance writers from the former colonies) and “translated literature” (which can draw from national writers). That is already the case in a prestigious collection like “Fiction & Cie” from Éditions du Seuil (which, in addition, has a foreign literature collection).53 However, as a result of the process of linguistic specialization, the existence of series of foreign literature ensures, as we have seen, a high degree of diversity in the languages of origin. Abolishing the distinction between French and translated literature would certainly have an adverse effect there. On the other hand, the diversity of languages of origin does not guarantee cultural diversity with regard to the inclusion of minorities and oppressed groups, which are still excluded in many countries from national recognition.

Translation does not only reveal changes in the book market but also in the collective cultural unconscious. Notably, the representation of the other is constructed there. Translations have participated directly in the construction of national identities and international cultural relations. As we have seen, it is through the paradigm of the “foreign” that translated literature is distinguished from French literature in France, on the basis of an identification between language, nation and country that has excluded minorities and colonized peoples. Even if national cultures do not form homogeneous wholes, the differing receptions of the same works from one country to another attests to the endurance of national cultures. But what translation has done, it can also undo. While the nation-states, France above all, continue to see it as a means for gaining recognition for their existence, it is at the same time a powerful tool for denationalization, as much for the multinationals that produce worldwide best-sellers as for the defenders of minorities who would promote “world literature.” French literary publishing continues to play a very active role in maintaining cultural diversity according to language of origin, since it serves, as we have seen, as a mediator for works written in peripheral languages, granting them access to translation into central languages such as English or semi-peripheral languages such as Spanish. But because of the relative decline in its consecrating power, this mediating role is increasingly destined for invisibility in the context of globalization.

—Translated by Jody Gladding

Notes

1. Lucien Febvre and Henri-Jean Martin, L’apparition du livre.

2. Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities.

3. Johan Heilbron’s “Toward a Sociology of Translation” proposes an approach to the world system of translation beginning with the center-periphery model that Wallerstein applied to the economy and with De Swaan’s transposition of it into a world system of languages in “The Emergent World Language System” and Words of the World.

4. Lawrence Venuti, The Scandals of Translation; Pascale Casanova, The World Republic of Letters; Johan Heilbron and Gisèle Sapiro, “Outlines for a Sociology of Translation.”

5. Pierre Bourdieu, The Rules of Art; Gisèle Sapiro, “The Literary Field Between the State and the Market.”

6. Casanova, The World Republic of Letters.

7. Alain Viala, Naissance de l’écrivain.

8. Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson, Literary France: The Making of a Culture.

9. Anne-Marie Thiesse, La création des identités nationales.

10. Norbert Elias, The Civilizing Process.

11. Michel Espagne, Le paradigme de l’étranger.

12. I refer to the concept of “literary field” as elaborated by Pierre Bourdieu, that is, a social space endowed with its own rules, relatively independent of economic and political constraints; see Bourdieu, The Rules of Art.

13. Itamar Even-Zohar, “The Position of Translated Literature Within the Literary Polysystem”; Pascale Casanova, “Consécration et accumulation de capital littéraire. La traduction comme échange inégal.”

14. Enrico Decleva, “Présence germanique et influences françaises dans l’édition italienne aux XIXe et XXe siècles,” 198.

15. Jean-Yves Mollier, La lecture et ses publics à l’époque contemporaine, 71–84.

16. Gisèle Sapiro and Boris Gobille, “Propriétaires ou travailleurs intellectuels?”

17. Christophe Charle, Naissance des “intellectuels” and Paris, fin de siècle, chapter 6.

18. Victor Karady, “La migration internationale d’étudiants en Europe, 1890–1940.”

19. Blaise Wilfert, “Cosmopolis et l’homme invisible.”

20. According to the data in the Bibliographie de la France, gathered for the period 1929 to 1971 by Claire Girou de Buzareingues, “La traduction en France,” 268.

21. Daniel Milo, “La bourse mondiale de la traduction,” 98.

22. Decleva, “Présence germanique,” 201–5.

23. Gérard Loiseaux, La littérature de la défaite et de la collaboration. On this period, also see Gisèle Sapiro, La guerre des écrivains.

24. Jeffrey Mehlman, Emigré New York; Emmanuelle Loyer, Paris à New York; Laurent Jeanpierre, Des hommes entre plusieurs mondes.

25. This evolution occurred first in the art market, as Serge Guilbaut has shown in How New York Stole the Idea of Modern Art.

26. Numerical data drawn from the study by Jean-Yves Mollier, “Paris, capitale éditoriale des mondes étrangers,” 380.

27. According to Buzareingues, “La traduction en France,” 271.

28. Ioana Popa, “Un transfert littéraire politisé.”

29. André Schiffrin, A Political Education.

30. François Cusset, French Theory.

31. Milo, “La bourse mondiale de la traduction.” In 1970, the USSR declared the same number of titles as the United States—that is, 79,000, according the UNESCO data; Robert Escarpit, “Situation du livre français,” 31.

32. Robert Laffont, Éditeur, 151.

33. Heilbron, “Towards a Sociology of Translation.”

34. Gisèle Sapiro, ed., Translatio, chapter 3.

35. UNESCO’s Index Translationum, which relies on national bibliographies, inventories all published translations, new editions included. Since the 1990s, the Syndicat National de l’Édition has calculated the number of contracts signed by French publishers with their foreign colleagues to acquire or sell translation rights, according to a classification by language. The accuracy of this data is limited because it depends on what publishers declare, which varies from one year to the next. As with the Index data, I use it here for information purposes only.

36. See Sapiro, ed., Translatio, 77, figure 3.

37. La quinzaine littéraire, April 1, 1966; Claire Girou de Buzareingues, “Les traductions en 1979,” Livre-Hebdo, February 17, 1981; Valérie Ganne and Marc Minon, “Géographies de la traduction,” 79.

38. Ganne and Minon, “Géographies de la traduction,” 64 and 79.

39. Fabrice Piault, “Littérature étrangère: la pente anglaise,” Livres-Hebdo, May 19, 2006.

40. Popa, “D’une circulation politisée à une logique de marché.”

41. Sapiro, ed., Translatio, chapter 3.

42. See, for example, Donald Morrison, “The Death of the French Culture,” Time, December 3, 2007.

43. Pierre Bourdieu, “La production de la croyance,” and “A Conservative Revolution in Publishing.”

44. Gisèle Sapiro, “Translation and the Field of Publishing,” and Les contradictions de la globalisation éditoriale.

45. André Schiffrin, L’édition sans éditeurs and The Business of Books.

46. For a more systematic comparison of the French and American publishing fields from the standpoint of literary translation, see Sapiro, “Globalization and Cultural Diversity in the Book Market.”

47. The share of translations in new romance novels reached 42.7 percent in 2005, according to Piault, “Littérature étrangère.”

48. Casanova, The World Republic of Letters.

49. For France, see Christophe Charle, “Situation du champ littéraire”; Gisèle Sapiro, “Je n’ai jamais appris à écrire.”

50. Hervé Serry, “La littérature pour faire et défaire les groupes.”

51. Camille De Toledo, Visiter le Flurkistan ou les illusions de la littérature monde.

52. Emily Apter, “On Translation in a Global Market.”

53. Hervé Serry, “L’essor des Éditions du Seuil et le risque littéraire” and “Constituer un catalogue littéraire.”