Every theater is in some way a globe. In the event of an impromptu street performance, for instance, people will naturally form a circle or semicircle around the performer. This spontaneous, if not instinctive, configuration has inspired theater architects and theater practitioners throughout the ages. Actor-director Louis Jouvet (1950) wrote that only the theatrical edifice can convey an idea of what theater really is, regardless of historical and cultural specifics. When alone in a theater, Jouvet explained, one may feel the space and be “englobed” (englobé) by it, and the lone spectator will then feel his own spatiality; he will be a space in a space.1 For Etienne Souriau (1950), in spherical theaters the fictitious universe emanating from the actors irradiates the audience, “englobing” spectators in an infinite sphere.2 In an inspiring essay published in 1998, philosopher Denis Guénoun postulated that theater is constitutionally global:

Au théâtre, s’exhibe une idée (une vue) de la cité rassemblée. C’est en quoi il est un théâtre du monde: la Cité se regarde comme analogue du cosmos—et le théâtre figure son unité sphérique—le Globe.3

[In the theater, an idea (a view) of the city assembled is exhibited. This is why it is a theater of the world: the city sees itself as analogous to the cosmos—and the theater presents its spherical unity—the Globe.]

Guénoun hypothesizes that the degree of circularity of a theater—stage and auditorium included—reflects a specific political climate. The rounder the theater is, the more communal and democratic its environment; conversely, the more it is quadrilateral, the more confrontational and authoritarian the regime that regulates it. In the theatrical arena, spectators see and experience themselves as a political collectivity. Drama is not political in and of itself, Guénoun argues, but rotund theatrical spaces are.

Theater happens in a theatrical space identified as such by those who have convened for the occasion of theater, spectators and actors alike. To be sure, theatrical spaces metamorphosed throughout the ages. Ancient Greek theaters have little in common with the enclosed theater houses we know today, except, of course, that spectators still watch actors enacting an action for them. As much as space is of the essence of theater, so is time. Every production being unique, theater happens in the moment. “Le théâtre n’existe qu’au moment où il a lieu [Theater only exists in the moment it takes place],” writes Jacqueline de Jomaron (1992).4 A play cannot be staged identically twice. A script in the form of a printed text may extend the lifespan of a play, but it will not reproduce a specific production; we all know this. We know that theater happens in a theatrical space once and for all. And the rest may well be silence, as Hamlet proverbially concludes in his tragedy.

If theatrical time flies, one can safely propose that some theatrical spaces outlive a unique production and may also host its future iterations, as well as other plays. Granted, a theatrical space may be dismantled after a single performance, as was often the case for itinerant troupes.

I will focus here on those permanent theatrical spaces that had historical significance, and that defined theater in France in the ancien régime. The Comédie Française is one such space. That the Holy See of French theater once dictated theatrical taste in the provinces and abroad is without question. The plays of Corneille, Racine, Crébillon, and Voltaire were translated, adapted, and staged in most of Western Europe in the eighteenth century. There was a French theater in Denmark, one in Vienna, and another in Saint Petersburg. Likewise, French neoclassical poetics traveled well and far. Rapin’s Réflexions sur la poétique, and d’Aubignac’s La pratique du théâtre were translated into English in 1674 and 1686. They instigated imitations by Rymer, mitigated endorsement by Dryden and contention by Howard; later in Germany, Lessing also reacted critically after reading Diderot’s essays on theater. The export of French theater constituted only one aspect of the multicultural cross-fertilization of theatrical practices in the ancien régime. Foreign troupes performed in Paris as well. The case of Italian actors rejuvenating French theater in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries has been made on countless occasions. Molière and Marivaux were indebted to Italian playwrights and actors. Less well known is the recent discovery of the short-lived presence of an English troupe in Paris in the early seventeenth century, most likely sponsored by the Prince of Wales.5 After the accusation of barbarism suffered by Shakespeare’s plays in the period, adaptations of the Shakespearean repertoire were staged in Paris; suffice it to mention Ducis’s renditions of Hamlet in 1769 and Le Roi Léar in 1783, followed a year later by Macbeth. The predominant Eurocentrism in dramatic settings of seventeenth century plays was criticized a century later. In fact, dramatic borders expanded considerably in the eighteenth century with such plays as Voltaire’s Alzire (1736) whose dramatic action takes place in sixteenth century Peru, and L’orphelin de la Chine (1755), not to forget Lemierre’s successful tragedy La veuve du Malabar (1770). As this all too brief sketch aims to highlight, French neoclassical theater stood at the crossroad of cultures, exporting itself, importing foreign troupes, incorporating dramatic traditions, and staging distant places, gradually respecting their local color. While neoclassical theater traveled and welcomed foreigners at home, the so-called théâtre à la française remained within the borders of the kingdom. In fact, foreigners visiting Parisian theaters, as well as many French spectators, mocked early French theater houses for not being global enough—indeed, the théâtre à la française was a rectangle.

This essay will not concern itself with French “classical,” or “neoclassical,” theater conceived as a text prescribed by neo-Aristotelian poetics. The Théâtre classique has long been a restrictive category defined by the trinity of Corneille, Molière, Racine, and by the rules of the three unities of time, space, and action dictated by Aristotle’s epigones. Corneille, Molière, and Racine were much more than playwrights delivering future canonical texts to a troupe; they took an active part in the overall conception and staging of their plays as actors in the case of Molière, or as declamation and acting coach in the case of Racine. The famous three unities were certainly Aristotelian in principle, but they were adapted to the reality of theatrical practices and constraints of the early modern French stage. And this was true of most aspects of dramatic structure; for instance, the division of plays into acts can be attributed to the influence of Horace, but it can similarly be explained by the necessity to snuff candles every so often lest the smoke obstruct the visibility of the stage. In its day, seventeenth-century theater was not a fixed entity with absolute rules, an ossified repertoire presented in a grand locale. Classical theater was a construction in progress, and so was its pantheon, the Comédie Française. A theater without an epicenter, a theater in the making, is what interests me. It is not until 1782, that the Comédie Française occupied a building designed specifically for theatrical representations. It was then that a theater was conceived and built for the first time in French theatrical architecture as a virtual globe. From the rectangle to the globe, is the title of the drama that follows.

Created in 1680 by the fusion of the troupes of the Hôtel de Bourgogne and the Hôtel Guénégaud, the Comédie Française, the royal theater, has long emblematized the excellence of French classical theater and served as the keeper of the repertoire for generations of spectators. At its beginning, the royal theater was a far cry from the well-groomed theater it has become. In the early seventeenth century, Paris had only one permanent theater house, the Hôtel de Bourgogne, owned by the Confrères de la Passion since 1548. Despite a monopoly to stage theatrical performances granted to the Hôtel de Bourgogne troupe, the actor Montdory opened the Théâtre du Marais in 1634 in a jeu de paume, the ancestor of the indoor tennis court. The overall design of both theaters was an elongated rectangle flanked by loges occupied by seated spectators, with a narrow and deep stage at one end and several tiers of seats at the other. Although the tiers of seats were referred to as the amphithéâtre, their disposition did not imitate the semicircular shape suggested by the name. Presumably, the amphitheater was significantly elevated above the ground level. Before it was renovated in 1647, The Hôtel de Bourgogne was approximately thirty-three meters long and thirteen meters wide. The stage had two levels, with the main stage being 13.6 meters wide and 10.6 meters deep and elevated a meter above the ground. Between the stage and the tiers of seats, an expanse of fourteen meters by nine meters constituted the parterre, where spectators stood for the whole duration of the play, sometimes for four continuous hours. Although this configuration, called théâtre à la française, was dominant at the time, it did not satisfy all spectators. The oblique visibility from the lateral loges was a common source of complaint, and so was the impropriety of the parterre where riotous outbursts often interrupted performances.

Exactly when the quadrilateral configuration was abandoned in the Bourgogne and Marais theaters under the influence of Italian architects and theater designers is still a matter of speculation. However, in 1641, Richelieu had a private theater built whose conception privileged the curvature of the French rectangle structure into a U-shaped structure called à l’italienne. When in 1660 Molière’s troupe had to be relocated after the destruction of the Petit Bourbon where it had been performing, it moved to the Palais Royal, built by Lemercier for Richelieu. Expelled from the Palais Royal after the death of Molière in 1673, the troupe occupied the Hôtel Guénégaud. In 1679, the already weakened troupe of the Hôtel de Bourgogne lost two of its main actors, the Champmeslé couple, to Guénégaud. The following year, La Thorillière, the director of Bourgogne died and the royal authorities seized the opportunity to fuse the two troupes into one.

As of October 1680, the royal troupe of the Comédiens du roi was the only troupe allowed to act in French in Paris and its environs. First hosted in the Hôtel Guénégaud, the royal troupe moved to a jeu de paume whence it was dislodged again in 1687, because the clergy deemed the theater too close to the Collège des Quatre Nations, a school built by Mazarin to host students from territories annexed during his ministry. The troupe finally settled in yet another former jeu de paume, the Hôtel des Comédiens du Roi located in the rue des Fossés St Germain. The new theater opened its doors in 1689. Nothing on the facade, save an inscription reading “Hôtel des Comédiens du Roi, entretenus par Sa Majesté, 1688,” indicated the function of the building and distinguished the edifice from those abutting it. Theater was primarily conceived as an interior performance under the aegis of the monarch, not yet as a freestanding public building announcing its function. The interior was the work of François d’Orbay, architect of the king.

The interior design revealed a fusion of the rectangular théâtre à la française and the théâtre à l’italienne, the latter being manifest in the curvature of the rear loges. However, the parallel benches of the amphitheater did not follow the curvature of the theater. The building was 17.55 meters wide by 35.10 meters long. The last balconies of the three tiers of loges extended beyond the auditorium and encroached on the stage. Those balconies, which intruded on the acting space, created a proscenium where actors declaimed their lines facing the audience. In addition, two rows of benches encumbered the stage limiting the acting space to a mere rectangle five meters by four meters until 1759. The presence of wealthy and noble spectators on the stage confirmed that the show was as much theirs as the actors’ and that the theater was as much a social parade as an art. In fact, the annexation of a large segment of the acting space by spectators points to the preeminence of the social spectacle over the theatrical spectacle. This is well rendered by Montesquieu in the Persian Letters. In the twenty-eighth letter, the unforgiving Persian Rica describes the show within the show at the Comédie Française:

Tout le peuple s’assemble sur la fin de l’après-dîner et va jouer une espèce de scène que j’ai entendu appeler comédie. Le grand mouvement est sur une estrade, qu’on nomme le théâtre. Aux deux côtés, on voit, dans de petits réduits qu’on nomme loges, des hommes et des femmes qui jouent ensemble des scènes muettes. . . . Ici, c’est une amante affligée, qui exprime sa langueur; une autre plus animée, dévore des yeux son amant, qui la regarde de même.6

[Toward the end of the evening, everyone assembles and goes to perform in a sort of show, called, so I have heard, a play. The main action is on a platform, called the stage. At each side you can see, in little compartments called boxes, men and women acting out scenes together. . . . Here there may be a woman unhappy in love, who is expressing her amorous yearnings, while another, with greater vivacity, may be devouring her lover with her eyes, and he looks at her the same way.]7

In Rica’s description, the multitude of mimed scenes played out silently by the audience members rivaled with the theatrical performance. The copresence of actors and spectators on stage and the show within the show contributed to the amalgamation of the dramatic space (fiction) and the theatrical space (stage and auditorium). In fact, the permeability of fictitious worlds and reality echoed the ambivalence of theatrical terms as illustrated in the excerpt from the Persian Letters. For instance, the substantive théâtre referred both to the acting area and the entire edifice. In the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the modes of representation on and off stage and the agents of the spectacle were diffracted and multiplied, as were the acting codes—from the stylized acting practices of the actors to the codified and varied social interactions of the spectators among themselves. The interior architecture of the theatrical space was of paramount importance, and architectural designs progressively aimed to congregate the many scenes and diverging points of view into one dramatic scene on stage and one spectatorial point of view directed at the proscenium. For many architects, the ellipse seemed to be the most appropriate configuration to achieve the unification of gazes.

The curvature of the rectangle of the théâtre à la française into an elliptically shaped auditorium was a long process that mobilized architects and theorists of theater alike in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. While the U-shaped theater was certainly an improvement over the rectangle, it still proved to be visually and acoustically poor. In his Dissertation sur la tragédie ancienne et moderne (1748), Voltaire complained about the configuration of French theaters and remarked that French plays were better served on foreign stages. He added: “Il serait triste, après que nos grands maîtres ont surpassé les Grecs en tant de choses dans la tragédie, que notre nation ne pût les égaler dans la dignité de leurs représentations [It would be unfortunate if, after our great masters have surpassed the Greeks, in so many ways in tragedy, our nation could not equal them in the dignity of their representations].”8 The final victory of the moderns over the ancients in the long quarrel that opposed the two parties in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries would come, according to Voltaire, when French theater architecture finally did away with the rectangular jeu de paume and celebrated the grandeur of the repertoire in a space that matched its magnificence. Just how Greek and circular French theaters should be was a point of contention.

Turning to the origins of theater in ancient Greece to modify and perfect the architecture of French theaters proved to be problematic for several reasons. According to the Abbé d’Aubignac, the ancients had built amphitheaters throughout their conquered territories as a token of their noble and civilizing intentions toward the inhabitants of annexed provinces. The military might deployed for conquest was balanced by the construction of amphitheaters. In d’Aubignac’s view, theaters legitimated conquests since they brought felicity to conquered peoples “par tout le monde,” throughout the world.9 Yet, the many Greek theaters did not survive the test of time. Built by men to resist the accidents of history, Greek and Roman amphitheaters turned out to be as mortal as their architects, d’Aubignac remarked. The furor of time, he explained, was seconded by divine reason in the destruction of ancient theaters because the spectacles they hosted were in contradiction with the humanity and the Christian doctrine promulgated in the Gospels. The partial destruction and burial of ancient amphitheaters under strata of debris and years of oblivion were therefore providential. When ancient amphitheaters were unearthed centuries later, they appeared in d’Aubignac’s description as hideous, amorphous and quasi-motionless corpses. However, the little life that remained in them sufficed to generate new theatrical forms and designs germane to reason and the teaching of Christ. From a defunct all-too-human global theater, an anointed national theater was reborn. The architecture of ancient theaters was thereafter of little relevance, d’Aubignac concluded, for the establishment of a modern French theater which would outdo the magnificence of its imperfect, albeit global, ancestor.

In addition to its religious shortcomings, the political function of theater in ancient Greece was also problematic for d’Aubignac and his contemporaries. D’Aubignac, for instance, considered that the republican subjects of Greek tragedy made them inappropriate for a seventeenth century audience:

Ainsi les Athéniens se plaisaient à voir sur leur Théâtre, les cruautés et les malheurs des Rois, les désastres des familles illustres, et la rébellion des Peuples pour une mauvaise action d’un Souverain; parce que l’Etat dans lequel ils vivaient, étant un gouvernement Populaire, ils se voulaient entretenir dans cette croyance, Que la Monarchie est toujours tyrannique, dans le dessein de faire perdre à tous les Grands de leur République le désir de s’en rendre Maîtres, par la crainte d’être exposés à la fureur de tout un Peuple, ce que l’on estimait juste.10

[Thus, Athenians enjoyed seeing in their theater, the cruelty and the misfortune of kings, the disasters of illustrious families, and the rebellion of the people against the wrong-doings of a sovereign; because the state under which they lived, was a popular government, they wanted to keep believing that Monarchy is always tyrannical, in order that the dignitaries of their republic lose the desire to control them, by fear of being exposed to the ire of the whole people, which was deemed just.]

Greek tragedy, for d’Aubignac, was largely antimonarchical, and so was the architecture, that hosted it. The vastness of ancient amphitheaters accommodating the multitudes assembled for the celebration of the Republic was obviously ill suited for a monarchical state. In the eighteenth century, Marmontel reiterated the critique of Greek amphitheater architecture:

Le théâtre a sa perspective: le nôtre est nécessairement moins vaste que celui des grecs . . . au lieu d’une nation assemblée, c’est un petit nombre de citoyens; au lieu d’un grand cirque en plein ciel, c’est une assez petite salle.11

[Theater has its perspective: ours is necessarily less vast than that of the Greeks . . . instead of a national congregation, it is a small number of citizens; instead of a large amphitheater in the open, it is a rather small theater.]

For Marmontel, as for many of his generation, Greek theater summoned the entire city to engage in a communal political act whereas French theater was a moral amusement, which pleasantly engaged select spectators individually. Individual moral edification rather than collective political education necessitated only a small edifice designed for that purpose.

The architecture of ancient amphitheaters was therefore inimical to a modern French audience so close to the actors that words alone could carry the whole of the spectacle and convey moral education. Plays could propagate a moral education because, as Marmontel explained, morals can be reduced to a transportable set of rules while, by contrast, politics is by nature contingent. Since, for Marmontel, passions and moral amendment are universal, unlike the political and religious historicity of events narrated in Greek tragedies, he concluded that Greek theater was but a “local opinion” while “notre théâtre est le tableau du monde [our theater is the picture of the world]” (6:313). Hence, the “immense circle” of ancient theaters was paradoxically more topical than global. On the contrary, the smaller elliptical shape of the French theater where passions ruled characters and morality reigned victorious, englobed the whole of humanity.

Published in 1782, Patte’s Essai sur l’architecture théâtrale provided the scientific basis for the dismissal of the circle as the perfect theater design. His demonstration was based on the acoustic and visual theories of his time. Schematically, Patte believed that sound travels forward, sideways, and upward from its source of emission, not backward or downward, thus ruling out the circle as the best acoustic design. The ellipse then proves to be the most suitable geometrical figure, since all lines starting from a point A as they strike the circumference of the ellipse are redirected to a single point B.12 If A is the stage and B the auditorium, then a sound emitted in A traveling in a straight line will necessarily end in B. In a semicircle, on the contrary, the line starting in point A as it strikes the circumference in a point B will be reflected in a point E; the trajectory from the same point A to a point C will be reflected in a point F, and so on. In that case, the voice of the actor located in A will not be directed at one single point, the auditorium, but lost in a multitude of points. In order to concentrate and maximize sounds emitted from the stage and directed at the auditorium, the ellipse is therefore the most appropriate geometrical figure. With regard to visibility, three conditions must be met: one, spectators should not be too far from the acting area; two, the height of the highest loges must be proportionate to the size of the opening of the stage so that all angles will be superior to thirty degrees; three, nothing must obstruct the visibility of the stage.

Patte’s remarks on ancient theater reiterate the critique of Marmontel. The gigantism of amphitheaters was contrary to his theory of proximity, and the distance between the stage and the auditorium was not conducive to sound despite ancient technical efforts such as acoustic vases. For Patte, the main difference between Greek and French theaters was their function: Greek theaters were built to accommodate thousands of spectators, hence the need for masks, acoustic vases, and cothurni, which transformed actors into colossal and disfigured statues, according to many critics. French theaters, by contrast, were built to maximize the voice and the visibility of the actors without mutilating their appearance to make them seen and heard from a distance. More importantly still, ancient amphitheaters did not allow the division of the auditorium along social lines, as was the case in French theaters with the parterre reserved for the poorer spectators, symbolically located below the loges occupied by the wealthiest. For Patte, the elliptical configuration was scientifically, aesthetically and socially the best. Yet, an increasingly strident critique of elliptical theaters was being heard. In 1773, Mercier regretted that the spherical design of ancient theaters had been compressed in French theaters: “on a resserré la sphere de la salle [The sphere of the theater has been compressed].”13 He maintained that his contemporaries had a “superstitious admiration” for ancient theaters. Rochefort, the editor of the 1785 edition of Brumoy’s Théâtre des Grecs, went so far as to identify the French theatrical experience as a private and solitary reading experience. Greek spectators, on the contrary, were animated by the communal spirit of the polis; going to the theater was a political act.14 As the eighteenth century unfolded, the global theater design offered the promise of social and political change, at least in theory.

In the second half of the eighteenth century, during the so-called retour à l’antique, architects debated the merits of the circularity of theater buildings. In 1749–50, under the aegis of Marigny, brother of Madame de Pompadour, the architects Soufflot and Dumont and painter Cochin visited the ruins of Herculaneum and studied in situ the architecture of ancient theaters. Their educational tour prompted reforms in many areas of pictorial and architectural arts. The authority of traditional sources of knowledge as Vitruvius’s De Architectura was put to the test of empirical research. In the Encyclopédie, for instance, Jaucourt criticized Vitruvius’s description of ancient theaters as architecturally inaccurate.15 The publication of voluminous texts rich with plates depicting ancient amphitheaters motivated numerous projects to rejuvenate French theaters. In 1765, Cochin published his Projet d’une salle de spectacle pour un théâtre de comédie. After precautionary paragraphs reminding his readers that his was only a conjectural project, Cochin reiterated the old complaint about the rectangularity of French theater houses. With the amphitheater seats located far from the stage, spectators could hardly hear or see the actors. Similarly, spectators seated in the lateral loges had to endure excruciating neck contortions to see the play. Cochin advocated the reconfiguration of theater houses as ovals so that most spectators would see and hear actors equally well. In his project, the number of loges reserved for persons of quality went from 168, the number of loges at the Comédie Française, to 132. The parterre of Cochin’s theater had room for an additional three hundred people compared to that of the royal theater. This design redistributed the allocation of space from the aristocratic loges in favor of a more plebeian audience. Although the project and its promise never materialized, its significance as a signal of changing theater architectural trends remains important.

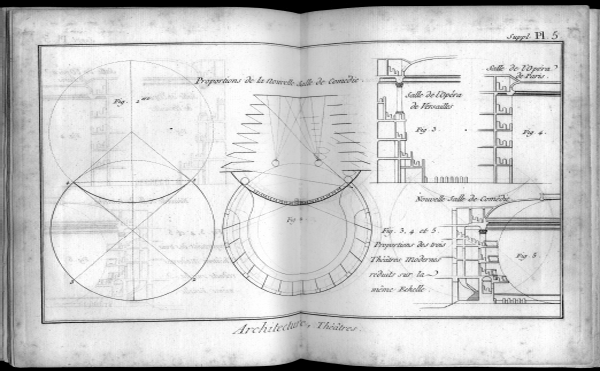

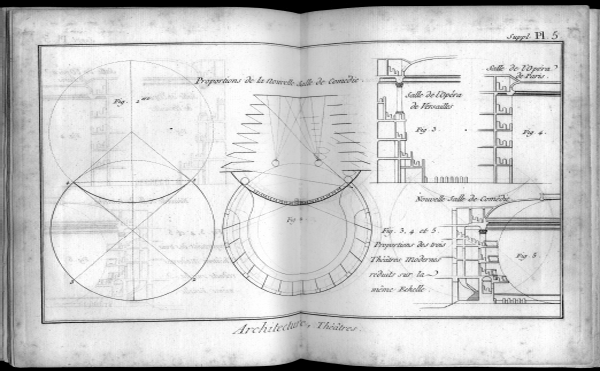

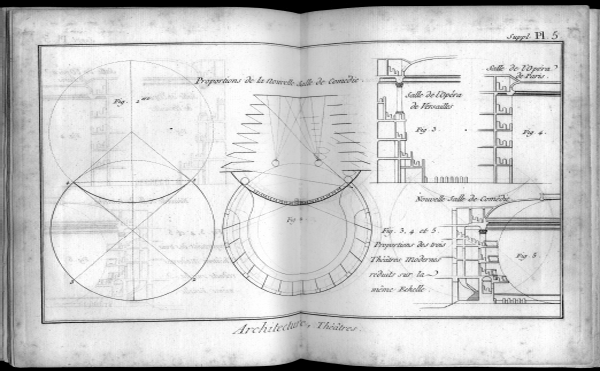

A concert of voices periodically denounced the insufficiencies of the obsolete Hôtel des Comédiens du Roi. From the late 1750s until the opening of the new Théâtre Français in 1782 (the future Théâtre de l’Odéon), myriad architectural projects flooded the desks of the Directeurs des Bâtiments du Roi (Directors of the King’s Buildings), Marigny and later d’Angeviller. Most of the submissions prior to 1770 proposed a convex facade for the new theater. Architect Jean Damun wanted to build a theater à la grecque, transposing the architecture of Greek amphitheaters to the French capital. A similar inspiration guided the architectural logic of two collaborators, Charles de Wailly and Marie-Joseph Peyre, whose project for a new theater was completed in 1782 after many major amendments. In their initial project of 1767–69, de Wailly and Peyre envisioned a convex facade whose curvilinear exterior and dome not only harmonized with the rotundity of the auditorium but also contained it. The rotund theater stylistically detached from linear neighboring buildings stood out as an edifice with a specific destination. This heightened visibility possibly prompted a revision of the project, which now privileged a decidedly massive and linear exterior while maintaining the innovative rotundity of the auditorium. De Wailly’s guiding principle, as stated in his Echelle des théâtres, consisted of two circles, one for the stage and one for the auditorium, intersecting in the proscenium. As Daniel Rabreau judiciously pointed out, de Wailly added to the bidimensional horizontal section of the auditorium its circular elevation, so as to represent its spherical volume. The spherical volume of the theater can be deduced from the cross-section in the lower right corner of the illustration.16 In the drawings of the theater, the auditorium was represented as a globe. Furthermore, in designing the Place de l’Odéon as a semicircle, de Wailly projected that the virtual continuation of the circle inside the theater would go through the proscenium, precisely where the two interior circles intersect. Thus, dramatic, theatrical and urban spaces were united in a virtual circle. In 1794, during the Revolution, de Wailly envisaged converting the semicircular Place de l’Odéon into an amphitheater with the facade of the theater serving as a backdrop for the political tribune located in front of it.

FIGURE 5.1 De Wailly, L’Échelle des théâtres, published in the Recueil de planches pour la nouvelle édition du dictionnaire raisonné des sciences, des arts et des métiers, 1778 (courtesy, The Herman B. Wells Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana).

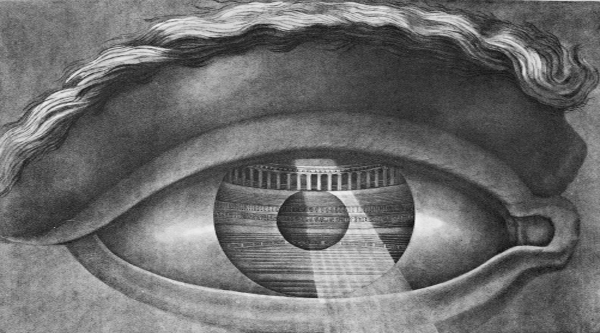

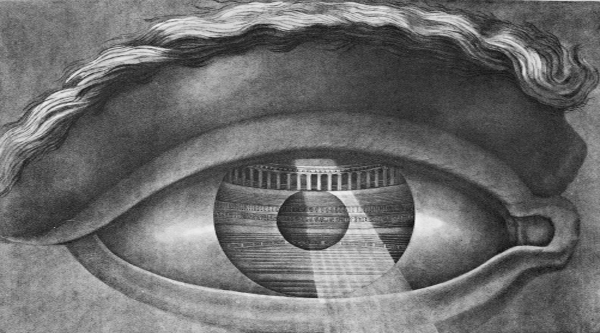

The fascination for the globe is also found in Ledoux’s Architecture considérée sous le rapport de l’art, des moeurs et de la legislation published in 1804. Ledoux is well known for his design of the theater of Besançon. His theories are replete with circular and spherical geometrical forms. The “Présentation symbolique de la Salle de Spectacles à travers la pupille de l’oeil” (Symbolical presentation of the theater through the pupil of the eye) exemplifies his architectural premise as the eye of the spectator reflects back and encapsulates an empty auditorium. Having meticulously debunked the rectangle and the ellipse, Ledoux stated, in a Rousseauesque tone that the purpose of theater is to see everything and to be seen by all. In an epiphanic style, the architect-poet finds in nature the ideal form, the circle. “Peuples de la terre accourez à ma voix; obéissez à la loi générale. Tout est cercle dans la nature [Peoples of the world, hear my voice; obey the general law. Everything is a circle in nature].” A long list of natural circles follows, such as the circles made by a stone thrown in water or the orbital rotation of the planets.17 Nature itself is a global theater, albeit an idealization of theater:

FIGURE 5.2 Claude Nicolas Ledoux, Coup d’Œil du Théâtre de Besançon, published in L’Architecture considérée sous le rapport de l’art, des mœurs et de la législation, 1804 (courtesy, The Fine Arts Library, Indiana University, Bloomington, Indiana).

C’est-là, oui, là où l’homme rendu à son état primitif retrouve l’égalité qu’il n’aurait jamais dû perdre. C’est sur ce vaste théâtre, balancé dans les nues, de cercles en cercles qu’il se mêle au secret des dieux. . . . c’est un peuple formé de cent peuples divers, c’est le point de réunion des droits respectifs des humains.18

[It is here, yes, where man returning to his original state regains the equality which he should never have lost. It is on this vast theater, floating in the air, from circle to circle that he communes with the secrets of the gods. . . . It is a people formed of a hundred different peoples, it is the meeting point of the individual rights of humans.]

The state of nature of theater, so to speak, is a circle encompassing all of humanity. The globe is a theater, and the theater is a globe. But, a global theater, it seems, remains only the dream of a visionary architect. The constraints of architecture invariably denature the idealized global theater of nature. In eighteenth-century theater design, the globe remains an ideal to attain, an architectural desire never satisfied.

It may be the case, as the history of theater architecture shows, that the rectangle and the circle respond to contrary political climates as Denis Guenoun suggested. The increasing curvature of theaters may have paralleled (or instigated?) political and social changes in France in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. But it should be remembered that as the auditorium became progressively rounder, order was imposed on the audience. In the new Comédie Française, spectators were no longer standing and interfering with the actors, but seated in silence. What is more, dramatic illusion and theatrical reality became separated by an invisible fourth wall as spectators were no longer allowed on stage. Yet, the globe serves as a fiction of origins, a natural theater of sorts before it materializes into a text and a building. The globe is the metaphor of theater par excellence. This is Rousseau’s lesson. To the question, “Ought there to be no Entertainments in a Republic?” he replies:

Au contraire, il en faut beaucoup! C’est dans les Républiques qu’ils sont nés. . . . Mais n’adoptons point ces Spectacles exclusifs qui renferment tristement un petit nombre de gens dans un antre obscur; qui les tiennent craintifs et immobiles dans le silence et l’inaction. . . . C’est en plein air, c’est sous le ciel qu’il faut vous rassembler et vous livrer au doux sentiment de vôtre bonheur. . . . Mais quels seront enfin les objets de ces spectacles? Qu’y montrera-t-on? Rien, si l’on veut. . . . Donnez les Spectateurs en Spectacle; rendez-les acteurs eux-mêmes; faites que chacun se voye et s’aime dans les autres, afin que tous en soient mieux unis.19

[On the contrary, there ought to be many. It is in Republics that they were born. . . . But let us not adopt these exclusive Entertainments which close up a small number of people in melancholy fashion in a gloomy cavern, which keep them fearful and immobile in silence and inaction. . . . It is in the open air, under the sky, that you ought to gather and give yourselves to the sweet sentiment of your happiness. . . . But what then will be the objects of these entertainments? What will be shown in them? Nothing, if you please. . . . Let the Spectators become an Entertainment to themselves; make them actors themselves; do it so that each sees and loves himself in the others so that all will be better united.]20

This passage, which has been read too many times as a denunciation of theater, may be stating the condition of its regeneration. No architecture, no object, just a multitude united in a configuration allowing everyone to see him or herself in everyone else. Is there a better way to achieve visual contact and universal communion than by forming a circle? Probably not. But, it takes just one person to leave the circumference and step into the circle to have the possibility of theater, and of politics. Some may hope with Rousseau that the wise will not take that step but rather continue to watch the comedy unfolding from the periphery. So many of us have already moved from the periphery to the center that the dire need of spectators is felt by philosophers like Rousseau, and by luminaries like Ledoux, whose global auditorium is eerily deserted. We have all become actors leaving the audience empty. The word theater comes from the Greek Theatron, the place from which one sees. As the auditorium of the main French theater was revamped into a globe in the late eighteenth century, the edifice and its function were simultaneously renamed Théâtre Français, parting with the old Hôtel des Comédiens du Roi. The new name is symptomatic of a concerted effort on the part of architects and theater professionals to extricate the term théâtre from its semantic ambivalence: stage or entire edifice? Regenerating theater by resurrecting its original meaning of auditorium may have been the dream of eighteenth-century architects. The world had been a stage; perhaps, it was time for the globe to become a theater for all.

Notes

1. Jouvet, “Notes sur l’édifice théâtral,” 10–11. Translations are mine unless indicated otherwise.

2. Souriau, “Le cube et la sphère,” 66–67.

3. Guénoun, L’exhibition des mots, 24.

4. De Jomaron, “Note au lecteur,” 11.

5. Howe, Le théâtre professionnel à Paris 1600–1649, 193.

6. Montesquieu, Lettres persanes, 172.

8. Voltaire, “Dissertation sur la tragédie ancienne et moderne,” 70.

9. Abbé d’Aubignac, La pratique du théâtre, 44.

11. Marmontel, “Eléments de littérature,” 6:318–19.

12. Patte, Essai sur l’architecture théâtrale, 16.

13. Mercier, Du théâtre, v.

14. Théâtre des Grecs, 1:233–34.

15. Encyclopédie, s.v., “Théâtre des Grecs.”

16. Rabreau, Le Théâtre de l’Odéon, 83.

17. Ledoux, L’architecture, 1:223.

19. Rousseau, “Lettre à d’Alembert,” 5:114–15.