‘Our only hope is to wake the sleeping heroes,’ the Grand Teller said, rummaging about on a high shelf.

‘What?’ Sebastian cried. ‘You can’t be serious. That’s just an old wives’ tale.’

Arwen looked at him quizzically. ‘There’s much truth in old tales.’ She found a carved chest and began to lift it down. Sebastian went to help her, for he was taller than she was, even though he was only thirteen. ‘Thank you, Lord Sebastian,’ she said. ‘You may put the chest on the table.’

Arwen looked at the group of children, crowded together in the tiny room. Tom was passing round the waterskin.

‘I meant what I said,’ Arwen urged. ‘Our only hope is to wake the sleeping heroes. There’s an old spell I’ve kept close for many years, in fear of just this day.’

‘What day?’ Tom demanded. ‘What’s happening? Who are those leathery creatures? And who is the tusked knight? Why are they attacking us?’

‘I do not know,’ the Grand Teller answered. ‘Enemies, that is for sure. I have had troubling omens this last moon, but nothing clear. I warned Lord Wolfgang, but he would not listen.’

‘How did they get in?’ Sebastian asked. ‘I thought the castle was impenetrable.’

Arwen looked shrunken and old. ‘I fear treachery …’ she whispered under her breath.

Another round of blows on the door echoed through the room. Sebastian’s spine stiffened. Those deadly creatures made him feel sick. They didn’t seem to care about having their arms and legs chopped off. And the way they sniffed the air! If he had not been a knight-in-training, Sebastian would have shuddered at the thought.

The wolfhound ran to the door, growling. Then he barked loudly as another blow hit the wood. ‘Shhh, Fergus,’ Tom said, clicking his fingers. The wolfhound went to his side, growling low. Sebastian imagined the bog-men out there, with only a wooden door between their sharp spears and him. He was the only one who really knew how to fight. It would be up to him to hold them off, if they were to break in.

He looked around, wondering if there was any way to escape. The room was roundish in shape, with gnarled and knobbly walls of living wood. Natural cavities and shelves were filled with books, boxes, and jars of seeds, feathers and shells. On the floor was a round hand-woven rug in reds and browns. A small stove was set against one curved wall, with a metal chimney rising up through the ceiling.

Beside a rocking chair was an odd round basket made of willow twigs. A tabby cat stood on a cushion inside the basket, back arched, spitting in warning. Quinn picked it up, soothing its fur with one hand. She rocked the basket with one bare foot, saying to Tom, ‘This is mine, you know. It’s the basket I was found in.’

‘You must’ve been tiny,’ Tom said.

She nodded, looking sad.

An owl was perched on the chair’s back, its ear-tufts erect, its feathers ruffled. It stared at Sebastian with round, golden eyes and he stared back. He had never seen an owl so close.

The only clear way out of the room was a ladder that led to a floor above. Sebastian wondered if there was any way out from there.

The banging on the door intensified. Suddenly the wood cracked. The children all jumped.

‘Do not fear,’ the witch said, opening the chest. ‘The door will hold another minute or two. Now listen to me carefully. You must remember what the spell says.’ She unrolled an ancient-looking parchment and read it, in a voice that quavered.

WHEN THE WOLF LIES DOWN WITH THE WOLFHOUND

AND THE STONES OF THE CASTLE SING,

THE SLEEPING HEROES SHALL WAKE FOR THE CROWN

AND THE BELLS OF VICTORY RING.

Elanor stared at the parchment. ‘But what does it mean? Wolves don’t lie down with wolfhounds.’ Fergus gave a small growl as if to say they certainly did not.

‘And stones don’t sing,’ Tom said. ‘Surely it’s just a nonsense rhyme, like the ones they sing to babies.’

‘There’s a lot of sense in nonsense rhymes,’ the Grand Teller said.

‘But how are we to make it happen, Arwen?’ Quinn asked. ‘We have a wolfhound.’ She patted Fergus on the head. ‘Do we just need to find a wolf? That shouldn’t be too hard.’

‘Making Fergus lie down next to a wolf will be,’ Tom said.

‘And how are we meant to make the stones sing?’ Sebastian demanded. ‘It’s a bag of moonshine!’

Arwen continued reading, slowly.

GRIFFIN FEATHER AND UNICORN’S HORN,

SEA-SERPENT SCALE AND DRAGON’S TOOTH,

BRING THEM TOGETHER AT FIRST LIGHT OF DAWN,

AND YOU SHALL SEE THIS SPELL’S TRUTH.

The children stared at her blankly.

‘But that’s impossible,’ Sebastian burst out. ‘There are no such things as dragons and griffins and unicorns and sea-serpents. They only exist in stories!’

‘Haven’t I told you already that there’s a lot of truth in old tales?’ asked Arwen. ‘Have you not been listening? You need to listen if you are to learn, Lord Sebastian.’

He went red and crossed his arms. ‘It’s a wild goose chase you’re sending us on. An impossible quest!’

‘The world is full of magical things, waiting for us to greet them,’ the Grand Teller replied. ‘You shall not see them with a closed heart.’

In the silence that followed, the banging on the door intensified. Someone out there had found an axe, and was chopping at a crack in the door. Fergus whimpered, his tail tucked between his legs.

‘Even if such beasts were real, how are we meant to catch them?’ Elanor said in a frightened voice.

‘If you are brave of heart, sharp of wit, strong of spirit and steadfast of purpose, there is nothing you cannot achieve,’ the Grand Teller answered. ‘But come. I cannot keep them out much longer. It is the darkest hour of the night and my strength is ebbing. I have some gifts for you.’

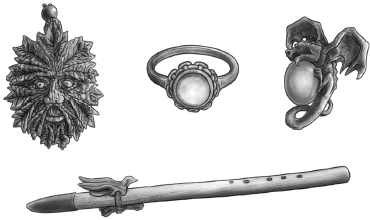

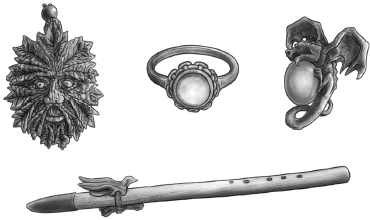

Arwen quickly unknotted the oaken medallion she wore about her neck, carved with the face of an old man surrounded by leaves. She passed it to Quinn. ‘He is carved from bog-oak and is many thousands of years old. He will help you to be wise.’

Quinn hung the medallion around her neck, as Arwen passed her the small bag of tell-stones. ‘Take care of them and bring them back to me,’ she said. Quinn nodded, her turquoise eyes bright with tears. Arwen then opened a chest and drew out a soft white shawl, lacy as a cobweb. ‘This is yours,’ she said. ‘You were found wrapped in it. It’s light, but it will keep you warm.’

As Quinn gratefully accepted the shawl, the Grand Teller gave a ring to Elanor. ‘It’s a moonstone. It’s called the Traveller’s Stone for it protects those that travel, whether by night or day, by land or sea, or in their dreams. It will help keep you safe.’

‘Thank you.’ Elanor slipped the ring on, and the stone glowed, round as the eye of a daisy, and set in small silver petals.

The Grand Teller then handed Sebastian a cloak-pin carved from golden-hued wood, in the shape of a dragon curled around a lump of amber. ‘This is carved from wood from the rowan tree,’ Arwen said. ‘Rowan wood is a powerful protection from evil.’

Sebastian nodded and pinned the wooden dragon to his jacket.

Finally, Arwen tossed Tom a small wooden flute. ‘It’s made from the wood of the elder tree,’ she began, but just then an axe chopped a great hole through the door.

‘Tom,’ she cried urgently, while rolling back her rug, ‘elder wood is very magical indeed. Use it wisely.’ Beneath the rug was a trapdoor. The old woman swung it open, revealing a set of steep steps leading down into darkness. She grabbed a lantern from the table and passed it to Tom, who thrust the flute into his pocket and snatched up his knapsack and bow and arrows. ‘The steps lead down to the harbour. Hurry! You must turn left, left, right, left, left, right, till you reach the Great Cave. Then just follow the water. Be careful. This mountain is riddled with dangerous caves and passageways. You do not want to get lost!’

Tom climbed down the steps, whistling for Fergus, who bounded past him, almost knocking him over. Elanor followed, looking white and frightened. Sebastian turned to beckon Quinn to hurry. She was hesitating, looking back at the old witch, her knapsack slung over one shoulder. The door was breaking apart under the onslaught of axes.

‘Aren’t you coming with us?’

‘I’m too old for such adventures,’ Arwen said. ‘Besides, I must stay and see what I can do to help here. There’ll be people wounded, frightened—’

‘But the bog-men,’ Quinn pleaded, ‘they’ll hurt you.’

‘Not I,’ Arwen replied. ‘Go, my sweet girl. Remember what I have taught you. Remember the spell. Don’t fail me.’

Quinn rubbed away her tears and climbed down the steps. Sebastian grasped his sword tightly, his shield hooked over one arm, and followed close behind her. The trapdoor thumped down above his head, and he was left groping his way down in darkness. Far below his feet, he could see the feeble glow of Tom’s lantern, shining through coiling snake-like roots.

Sebastian gulped. He did not like small, dark spaces. But there had to be a way out, he told himself. He squared his shoulders and kept climbing down.

But the steps kept winding down, down, down, and soon Sebastian’s legs were aching. He heard Elanor’s breath coming in little gasps and wondered if she was crying.

A long time later, Tom’s voice came wavering through the gloom. ‘We’ve reached a passageway. At last. Did she say to turn left or right? I can’t remember.’

‘I don’t remember either,’ Elanor quavered.

‘Left,’ Quinn said.

‘Right,’ Sebastian said.

‘It was left,’ Quinn insisted, impatiently.

‘Right,’ Tom replied. ‘Sorry, I mean, yes, fine, left it is.’

The light veered to the left.

‘Who put you in charge?’ said Sebastian furiously, at last reaching the bottom of the steps.

‘I’m the one with the light,’ came the distant answer. ‘Feel free to turn right if you want!’

The light went on down the left-hand passageway, growing dimmer till it disappeared.

Sebastian stumped after it, promising himself he would pummel that pot-boy to pieces the very first chance he got.