10

TECHNOLOGY: INVENTIONS THAT CHANGED LIFE AND WARFARE

“Technology is a gift of God. After the gift of life it is perhaps the greatest of God's gifts. It is the mother of civilizations, of arts, and of sciences.” — Freeman J. Dyson

One of the great ironies of history is that the greatest advances in technology, thought, and the arts often occur during times of warfare and strife. America's Civil War is certainly no exception to this rule. It saw the introduction or improvement of weapons, inventions, and industrial processes. Technological advances, such as telegraphy, railways, and mass production made it possible to raise, transport, and supply the huge armies that fought the Civil War. In the 1860s, America was in the midst of its Industrial Revolution, being transformed by advancing technology into an industrialized rather than an agrarian society. When war broke out, each side was driven to bring to bear whatever advantages it could. Ultimately, the North, a more industrialized region and the beneficiary of more and greater modern technology, prevailed and won the war. And, as horrible as the Civil War was, the technology advanced and produced during the conflict subsequently helped the United States become the world power it is today.

Like so many other conflicts, the Civil War proved that technological superiority alone is usually not enough to win a war; if it had been, the war would have ended in 1861 and not dragged on for four long, bloody years. Northern technological superiority, however, meant that the war was an uphill battle for the South from the beginning, and a fight that the South eventually was unable to continue.

Many inventions associated with later ages saw their earliest incarnations during the Civil War. Military advances included the introduction of many new types of weapons and equipment, among them land mines, repeating rifles, automatic weapons, revolving gun turrets, armored warships, long-range sniper rifles, railroad artillery, double-barreled cannon, and the first naval mines (many of these weapons are discussed in chapter 13).

Technological advances such as telegraphy, railways, and mass production made it possible to raise, transport, and supply the huge armies that fought the Civil War.

The military also made great advances in the usage of existing types of weapons and equipment, including observation balloons, hand grenades, submarine and semisubmersible vessels, mobile siege artillery, and rockets.

Medical advances included vast improvements in medical care, improved prosthetic limbs, the first orthopedic hospital, improvements in pharmacology, techniques for handling infection and the spread of disease, and anesthetics.

Other technological advances included the first fire extinguishers, periscopes, the first railroad signal system, the first oil pipeline, great advances in photography (see appendix A), improved telegraphy, mobile field communications, canned food, improvements to the factory system, instant coffee, and rudimentary refrigeration.

Technology in the North

In the North, on the eve of the Civil War, more than one million people worked in some 100,000 factories of varying sorts and sizes, which included virtually all of the nation's weapons manufacturers and shipyards. Several parts of the North, especially the New England states and New Jersey, were also noted as being sites of particular innovation and inventiveness.

Northern ability to produce whatever it needed, rather than import it from other countries, simply eclipsed that of the South. A striking example of this is that, in 1860, the textile factories of a single Northern city, Lowell, Massachusetts, had more spindles turning thread than did the entire South.

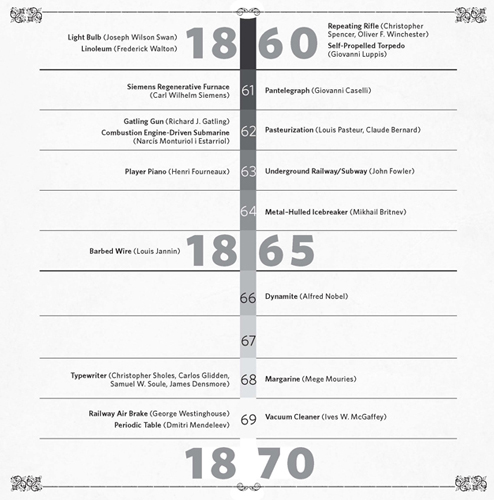

INVENTIONS OF THE 1860s

This time line shows some of the top inventions from the decade of the Civil War. Many of them were at least peripherally military in nature.

Technology in the South

At the outbreak of the Civil War, the South had about 100,000 workers employed in a mere 20,000 factories and workshops. Some of these were very technologically advanced, such as Augusta Powder Works, which produced some of the best gunpowder used on either side. Overall, however, the South probably had about a tenth the industrial capability of the North. This capacity diminished as the war progressed, too, as the South was unable to furnish the raw materials it needed to produce goods in its factories, and Southerners had to become adept at improvisation and devising substitutes as needed.

At the beginning of the war, for example, the Confederacy had only two major metal foundries, Leeds Company in New Orleans and Tredegar Ironworks in Richmond, Virginia. It lost Leeds when Union forces captured New Orleans in April 1862 and, less than a year later, Union forces occupied Tennessee, depriving the Confederacy of its primary source of iron. This left Tredegar, as well as many smaller factories, at a standstill for months at a time for want of raw materials to work with. Nonetheless, throughout the course of the war, Tredegar produced thousands of artillery pieces, as well as armor plating for ironclad warships.

In 1860, the textile factories in Lowell, Massachusetts, had more spindles turning thread than did the entire South.

Southern ironworks produced only a quarter as many cannon as did factories in the North, but this still represented a high level of ingenuity and dedication. A side effect of this was that even the limited numbers of consumer goods that had been produced prior to the war were no longer manufactured in the Confederacy.

Prior to the war, of course, the South was able to import whatever products of technology and industrialization it needed. Indeed, it was technology that had made the institution of slavery profitable by the time of the Civil War. By the early 1800s, slaves could not pick or process enough cotton to make them highly profitable. The invention of the cotton gin, however, allowed far more cotton to be grown and processed by fewer slaves, ensuring the economic viability of the slave-based plantation system, which otherwise would have likely died a natural death within a few generations. Cotton became the world's cheapest and most widespread textile fabric.

Military Technology

Military technology is very reactive and tends to improve only in response to specific threats, conditions, or needs, and technological advances in some areas prompt corresponding advances in others. The heavy rifled artillery pieces of the Civil War, for example—which could blow apart existing masonry fortresses—necessitated improvements in fortification. And the war's deadly weapons in general prompted improvements in many areas, from battlefield medical care to prosthetic limbs for soldiers who had been horribly maimed.

Military tactics, too, had to change in the face of improved technology. Battlefield tactics at the beginning of the war were based on principles little modified since the Napoleonic Wars (1793– 1815). Commanders studied the strategies, techniques, and maxims of those wars, and soldiers on both sides were taught corresponding drill and maneuver from a variety of training manuals.

One of the foremost of these was Rifle and Light Infantry Tactics (subtitled For the Exercise and Manoeuvres of Troops When Acting as Light Infantry or Riflemen), written in 1855 by William J. Hardee, a veteran of the Mexican War who served as a Confederate general during the Civil War. It was better known among soldiers as “Hardee's Tactics” or the “Hardee Manual.” Other contemporary texts included Scott's Tactics, “Casey's Manual” (Infantry Tactics for the Instruction, Exercise, and Maneuvres of the Soldier, a Company, Line of Skirmishers, Battalion, Brigade or Corps D'Armee), “Gilliam's Manual,” and a manual on bayonet fighting that had been translated from the French by Union Gen. George B. McClellan.

Unfortunately, these strategies and tactics assumed an antiquated level of technology in which soldiers bearing smoothbore muskets with limited accuracy and range had to line up on open ground in tight formations within a few hundred yards of the enemy and blaze away at each other in volleys, eventually following up with a spirited bayonet charge. Rifled muskets, however, allowed defenders to shoot apart tightly-packed enemy formations while still hundreds of yards away. Many commanders, nonetheless, persisted in employing the tactics of a previous age right through until the end of the conflict, something that contributed to it being the United States' costliest war ever.

Tactics did evolve, of course, in response to the new technology. Referred to as “skirmisher tactics” or “Zouave tactics,” they emphasized fighting in small groups and loose formations, making good use of cover and charging for short distances before dropping behind cover.

Improvements in Artillery

Industrialization allowed for the manufacture of more powerful, accurate artillery pieces than had ever before existed, and for vast improvements to explosive shells and other types of artillery ammunition. Such improvements included breech-loading mechanisms, rifled barrels, smokeless gunpowder, systems for absorbing recoil, and vastly superior metallurgy.

Many commanders persisted in employing the tactics of a previous age right through until the end of the conflict, something that contributed to it being the United States' costliest war ever.

Cannon makers also developed new ways to construct guns so that they could withstand heavier powder charges, firing heavier projectiles further and with greater velocity. Thomas J. Rodman, for example, developed a process for producing incredibly strong gun barrels by casting successive layers of the tube around a removable metal core that was cooled by water. As each layer cooled, it shrank and further compressed the layer beneath it. Robert Parker Parrott created artillery barrels by wrapping wrought iron or steel hoops around a central tube made of cast iron or steel.

Redoubts, trenchworks, and other forms of modern fortification were used extensively during the Civil War for the first time.

Fortifications and Siege

In addition to modern tactics, soldiers who survived their first experiences in battle learned to take cover behind trees, fences, walls, and anything else available, and to make use of firing pits, trenches, and other means of defense. Although it had existed in a much simpler form since the seventeenth century, trench warfare was adopted and refined throughout the course of the Civil War, foreshadowing the way conflicts of the future would be fought. And, just as the trenchworks were a reaction to highly-lethal small arms, weapons were developed during the Civil War to harry or kill soldiers within such defensive works, including hand grenades and relatively light mortars.

Just as infantrymen had to react to the power of modern small arms, so too did engineers have to react to the power of the newest artillery pieces. Most of the forts in existence when the Civil War began were “Third System” fortifications, planned in the decades following the War of 1812 and constructed according to the canons of the early nineteenth century. These polygonal brick forts were designed to withstand the weapons of an earlier age and not heavy, rifled artillery pieces firing explosive shells; such guns, especially when used in mass, wreaked havoc on the outdated fortifications. Fortifications built during or after the war utilized low, earthen walls that could absorb the force of artillery projectiles, rather than try to resist or deflect them with high stone walls.

After making history as the flash point for the Civil War in 1861, Fort Sumter came under fire again in 1863, this time from Union siege artillery. For twenty-two months, the fort withstood bombardment and was almost completely reduced to rubble. Pounded into small pieces, however, Sumter became even more defensible, and Southern defenders burrowed into the rubble, living in subterranean bombproofs and firing their guns from behind berms of smashed masonry.

Many sorts of obstacles were used on Civil War battlefields, including chevaux de frise, sharpened stakes affixed to logs that were especially effective at impeding cavalry.

Medical Technology

When the Civil War broke out, contemporary medical technology proved unable to adequately cope with the widespread diseases and horrific wounds it would be faced with over the ensuing four years. Blood transfusions, penicillin and other antibiotics, antiseptics, hypodermic needles, X-ray machines, and innumerable other innovations that could have helped save innumerable lives did not yet exist.

More soldiers actually perished from disease than from any other causes during the Civil War. In general, for every man who died from wounds, there were two who succumbed to disease.

In 1861, the U.S. Army Medical Corps consisted of a mere ninety-eight surgeons and assistant surgeons (in the mid-nineteenth century, doctors were usually referred to as surgeons). Its equipment consisted of a few dozen thermometers, no microscopes (not until 1863), and no working knowledge of devices like the laryngoscope, stethoscope, or ophthalmoscope.

Hypodermic syringes did not exist either. When painkilling drugs had to be administered, they were generally rubbed or dusted into open wounds, or administered in pill or solution form. Morphine and other opiates were the most common sorts of painkillers, and many soldiers became addicts as a side effect of their widespread usage; after the war ended, they could easily obtain such drugs at local drugstores.

By the end of the war, surgeons had learned much about wounds, diseases and drug addiction—much more than they ever could have learned spared the horrors of the war—and medical technology advanced as a result of their knowledge.

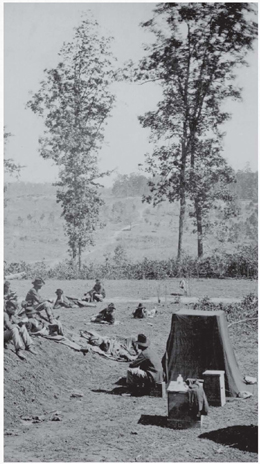

Patients, doctors, and volunteer nurses at Carver Hospital in Washington, DC.

Hospital design was one area of improvement. During the era of the war, new hospitals were designed as a series of pavilions connected by covered or enclosed walkways. Soldiers were separated based on their particular wounds or afflictions, reducing the spread of disease. Modern hospitals are based on this model today.

Advances were also made in areas peripheral to the treatment of wounds and illness. Improvements in photography, for example, allowed for wounds and their treatments to be studied by doctors after the war.

Because many families wanted their dead loved ones shipped home, great strides were also made in the science of embalming during the Civil War. A whole new profession concerned with embalming developed during this period, and families who could afford it could hire an “embalming surgeon” to preserve the body of a dead soldier and bring it back home for burial.

The role of medical personnel on the battlefield changed, too, and one important concept advanced during the war was the idea that doctors, nurses, and orderlies were neutrals who should not be shot at or taken prisoner.

Medical Training

Medical schools were common during the Civil War but, unfortunately, many of them provided little practical training. In the nineteenth century, training for surgeons typically consisted of three thirteen-week semesters of medical school. Some fairly good medical schools did exist, mainly at established colleges and universities, such as Princeton and Yale. Programs at such schools lasted one or two years and consisted almost entirely of classroom instruction, with just a few weeks of medical residency. Training during each year was identical and, consequently, some students did not bother to study a second year, although this was generally recommended.

No sort of medical licensing boards existed, however, so little could be done to regulate doctors. In fact, no training or certification of any sort was required for someone to call themselves a surgeon or doctor, and quacks and incompetents were not uncommon.

Causes of Death and Injury

Although battlefield injuries were among the most dramatic and horrible ways soldiers were killed, more actually perished from disease than from any other causes during the Civil War. In general, for every man who died from wounds, there were two who succumbed to disease. In camps and prisons alike, soldiers suffered the effects of overcrowding, inadequate waste disposal, malnutrition or even outright starvation, and parasitic infestation, all factors that caused diseases like influenza and cholera to spread almost unchecked.

Wounds, of course, were not to be underestimated. Because no sorts of antibiotics or antiseptics were available, even a minor wound could easily become septic or gangrenous, killing a soldier within days or requiring the amputation of an infected limb.

Nearly nineteen out of every twenty wounds were inflicted by small-arms fire and the worst of these were caused by cone-shaped, soft lead rifle slugs called minié balls. Minié balls could be fired at much higher velocity than the round musket balls of a generation before and were far more destructive to internal organs. Such projectiles would also flatten out upon impact with the long bones of the legs and arms, blowing them into splinters and requiring them to be amputated. Even wounds that did not require amputation or were not immediately fatal often became infected and ultimately proved mortal.

Amputation

During the Civil War, three out of four operations performed on soldiers by surgeons were amputations. It might seem to a casual observer that surgeons were taking the easy way out with amputation, that they were indifferent or incompetent, or that limited resources forced them to simply remove limbs rather than perform more delicate surgery. Unfortunately, while some contemporary doctors were truly incompetent, even the best doctors simply had no choice but to remove limbs irreparably mangled by minié balls, explosive shells, and other weapons of the age. Bones shattered by bullets had no chance of regenerating.

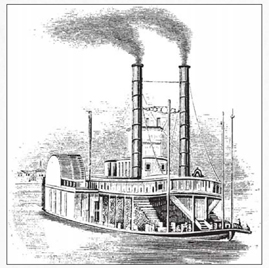

Paddlewheel steamers were used extensively for commerce along America's rivers and inland waterways. During the war, such vessels were used for ferrying troops, as hospital boats, and were sometimes armed and used as warships (although they were not generally considered sturdy enough for this role).

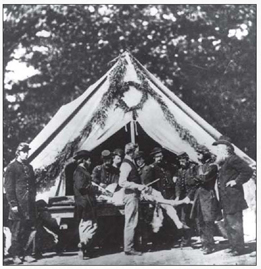

This famous Civil War image shows Union doctors performing an open-air amputation at a hospital tent at Gettysburg. Although amputation was common, this scene is likely posed and not taken during actual surgery.

Surgery in the field was usually performed in makeshift field hospitals, sometimes on operating tables consisting of a few boards laid across a pair of barrels. Chloroform was often available (more so in Union hospitals than those of the Confederacy), and a rag or sponge soaked with it would be held over the face of the soldier being operated on. This was in itself a dangerous procedure, and could result in chloroform poisoning if not removed often enough. In the absence of chloroform, a few shots of whisky might do; in any case, some sort of anesthesia was usually administered, and it was uncommon that nothing was available but a bullet or stick to bite down on. When no anesthetic was available, the risk of a soldier dying from shock was much greater.

The entire amputation process generally took about fifteen minutes, although some doctors were noted for performing amputations even more quickly.

Amputation usually consisted of the following steps. First, the surgeon would cut off blood flow to the afflicted limb with a tourniquet. Then, after selecting the place where he would have to cut through the limb, he would slice through the surrounding flesh and connective tissue with a scalpel. He would then use a “capital saw”—a tool with replaceable blades that looked much like a hacksaw—to saw through the bone. Once the limb was completely removed, the surgeon would toss it onto a pile of other arms and legs and sew up the major veins and arteries with sutures (silk thread in the North, cotton thread in the South). The soldier would immediately be removed so another could take his place. The entire process generally took about fifteen minutes, although some doctors were noted for performing amputations even more quickly.

Amputation was most effective if performed immediately after a wound occurred. Mortality rate for soldiers who received an amputation within twenty-four hours of being wounded was 25 percent, a rate that doubled to 50 percent for soldiers who received an amputation more than a day after being wounded. Nonetheless, and as horrible a solution as it was, amputation saved the lives of many soldiers for whom there otherwise would have been no hope at all.

Medical Transportation

Medical personnel had to deal with greater numbers of wounded soldiers than they ever had before, and, as a result, numerous means of transporting the injured were developed.

Ambulances were among the most common. Two-wheeled varieties provided a very bumpy ride, and many severely wounded soldiers died after being transported in them. Four-wheeled ambulances were also used, and these provided a more comfortable ride. Horses were preferred to mules for ambulances, as they provided steadier service.

Steamboats, train cars, and barges were also modified as conveyances for the wounded. Converted passenger cars could carry up to three-dozen wounded soldiers, the least seriously wounded in stretchers hung from the ceilings and the most severely injured on wooden slats inserted across the seats.

Farm Technology

Agriculture in the United States had been transformed in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Improved understanding of chemistry helped fertilization and livestock feeding practices; productivity was increased through improvements in plant and animal breeding; inventions like steam-powered grain-threshing machines, sugar mills, and the cotton gin radically improved the yield of crops that had once been highly labor-intensive. Canals, railroads, and steamboats allowed surplus produce to be shipped into the growing urban areas, encouraging farmers to increase their production for profit.

Horse-powered farm machinery dominated American agriculture throughout the nine-teenth century and reached the height of its effectiveness during this period. Elaborate horse-powered agricultural equipment increased labor productivity immensely and allowed new land to be brought under cultivation. Teams of horses pulled cultivators, harrows, mowers, plows, hay rakes, and reapers; activated combines and threshing machines; and performed many other useful tasks.

Rail Transportation

In 1861, most of the country's railroad tracks and rolling stock, along with the workshops needed to manufacture and repair them, existed in the North. As a result, the Union was able to use the railways as a significant tactical, strategic, and logistical tool.

The South had fewer miles of rail line, much less rolling stock, an inability to replace either, and handicaps in maintaining them. But, the Confederacy used the railways to accomplish a handful of impressive results, including their victory at the first Battle of Bull Run and the transfer of Lt. Gen. James Longstreet's corps in time for the Battle of Chickamauga, widely considered a master stroke. As Jeffrey N. Lash explains in Destroyer of the Iron Horse, however, a differing philosophies between Northern and Southern generals led the latter to not fully consider railways to the extent that their adversaries did, nullifying even the limited resources at their disposal.

Indeed, many otherwise exemplary Southern generals (notably Joseph Johnston, who had a strong background in railway construction, technology, and design) had a blind spot when it came to the possibilities offered by the railways. Some Confederate generals did try to make the most of railway resources, and Leonidas Polk was their most proficient rail general. Overall, however, this inability to exploit such an important resource tarnishes to a great extent the popular notion that Confederate generals were vastly superior to their Union counterparts.

This deficiency was, however, not limited to the Confederacy. Several high-ranking Union generals also failed to use rail to its fullest advantage, among them Maj. Gen. Henry Halleck, Maj. Gen. George McClellan, and Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans.

When used properly, railways could be used to quickly transport fresh troops to a new theater, evacuate worn units, or supply garrisoned areas. As a result, rail lines were often military targets. Quick ways to disrupt rail transit—employed especially by raiding troops—included tearing up railway tracks and ties, tipping over locomotives and cars, and blowing up railway bridges. Possible disadvantages to these methods were that they could make a section of line unusable to the side doing the destruction (which was not an issue if they would not have opportunity to use it anyway), and that their effects could be undone with relative ease once the vandals had retreated back to their own lines. Indeed, some Union army engineers made prefabricated bridge components and reached the point where they could replace demolished bridges within twenty-four hours.

Some Union army engineers made prefabricated railroad bridge components and reached the point where they could replace demolished bridges within twenty-four hours.

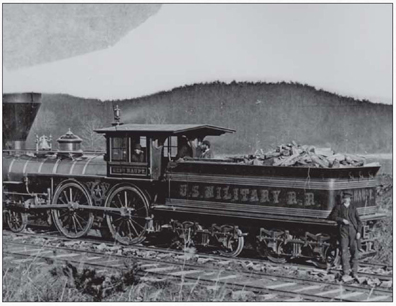

The “General Haupt” was an engine built for the a U.S. Military Railroad in 1863. Railroads were a quick way to transport troops and supplies.

More lasting methods of disrupting rail traffic included pushing rolling stock off bridges or into ravines; packing wood or coal in or around rolling stock and igniting it; and pulling up railroad ties, heating them in a fire, then wrapping them around trees to make the ties permanently unusable (a method employed by Sherman's troops when marching through Georgia in 1864).

Railroad equipment was expensive and its destruction could prove costly. In 1861, a heavy locomotive cost $9,000 and a passenger or freight car cost $2,200. As the war progressed, prewar costs became moot, and a new locomotive could not be had in the South at any price in the latter half of the war.

Communications

Many new forms of communications were developed prior to and during the Civil War, most notably the telegraph, while other innovations of the period were not widely used. For example, in 1843, Scottish physicist Alexander Bain invented a facsimile machine that could send a copy of image or printed material over telegraph lines. A working version of the system called the Pantelegraph was built in 1861 in Paris by Italian physicist Giovanni Caselli, and four years later he launched the world's first commercial telefax service between Paris and Lyon.

Telephones were invented eleven years later and came into limited use in 1877, during the last year of Reconstruction.

The amount of mail being sent increased dramatically during the war, as thousands of soldiers and their families tried to stay in touch with each other. One measure the Federal postal service employed to cope with this increased demand was to divide posted materials into first-class, second-class, and third-class mail. During this period, the postal service also began to provide free delivery in cities.

A wide array of daily and weekly newspapers were available during the Civil War, providing citizens detailed coverage of the war that had previously been unavailable.

The famed but short-lived Pony Express reached its peak during the Civil War. Established on April 3, 1860, in hopes of winning a mail contract, the courier service strove to deliver mail from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, California, about two thousand miles, in a mere ten days.

Pony Express employed some eighty riders during its brief tenure, including the famous “Buffalo Bill” Cody. Each rider rode seventy to eighty miles at a time, stopping to change horses at stations along the route, which were built at intervals of about ten miles. Despite its success, the Pony Express lasted little more than a year-and-a-half—until October 24, 1861—and was rendered obsolete by the linking of the East and West Coasts by telegraph, a considerably faster and cheaper means of communication.

Telegraphy

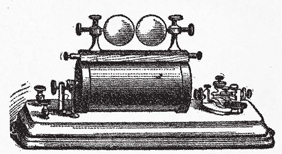

Message transmission during the nineteenth century was fairly simple. An operator used a key or switch to send short pulses of electricity to the telegraph line from a battery. Messages were sent by dispatching these pulses in patterns that formed codes representing letters and numbers.

Inventors Samuel Morse and Alfred Vail made great improvements to this early sort of receiver and modified it to print dot and dash symbols corresponding to electric pulses of short and long duration, creating what became known as Morse code. In 1844, Samuel Morse sent his first famous message, “What hath God wrought,” from Baltimore to Washington, DC. His receiver was widely adopted, and telegraphy soon achieved a central role in communications. Western Union was founded shortly thereafter to provide telegraphy services and had extended its lines to California by 1861.

Telegraphic transmission was facilitated by relays, electromagnet receivers that operated switches and allowed power from a local battery to key a further length of telegraph line. At the time of the Civil War, relays were the only form of amplifier available to telegraph engineers.

Because telegraphers could easily distinguish and transcribe Morse's dot-and-dash signals onto paper by hand, devices for recording signals directly onto paper, used earlier in the century, were largely abandoned. New methods, however, were devised by other inventors.

Publications and Print Media

People learned about the major events of the war through a wide variety of publications. In many cases, newspaper stories were sensationalized, inaccurate, or even outright fabrications, and soldiers often commented that what was going on around them bore little resemblance to what the newspapers and newsweeklies were reporting. Nonetheless, people on the home front were better informed about what was happening on the battlefields than in previous conflicts.

Contemporary news publications tended to be much smaller than their modern counterparts in both length and dimensions. “Tabloid”-size publications were more common for mainstream daily publications than today, and many dailies were eight pages long (that is, two folded broadsheets, each comprising four pages) or shorter. Southern papers, in particular, shrunk in size along with available resources in general, and were often printed on less-than-ideal materials. Because of a shortage of newsprint, for example, one 1863 edition of the Opelousas Courier was printed on wallpaper.

Civil War-era news publications were also text-heavy, and frequently the front pages included no illustrations. There were exceptions to this, most notably Frank Leslie's Weekly (a.k.a., Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper), and when such publications did include artwork, the most common sorts were engravings and lithographs of scenes from the war, maps, and political cartoons.

During the war, reporters near the front would file their stories with their newspapers via telegraph. Because telegraphy was subject to so many vicissitudes, such as lines being cut by enemy raiders, reporters developed an “inverted pyramid” style of story writing, in which the lead paragraph of a story included its most critical information, and each subsequent paragraph contained information of decreasing importance. Thus, even if only the first paragraph went through, a newspaper might still have the basis for a story. This is the basic format used in most print news stories to this day.

CIVIL WAR PERIODICALS

Following are some of the periodicals available to people during the Civil War or the period of Reconstruction that followed it. A number of these publications are still read today and some have historic copies available online or on microfiche at libraries, particularly in the areas where they were originally published. There are many others that existed only briefly, in some cases after being founded during the war but unable to prevail during it.

A publication's affiliation with a particular city is noted (unless such information is obvious from the name or is not relevant), as are the dates publications were founded and, if applicable, when they ceased publication.

Names given are those in use during the era of the war and, in some cases, their names changed at some point before or after the conflict, often due to mergers with other publications (for example, the Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser was part of the Baltimore News-American when it folded).

Northern News Publications

» Baltimore American and Commercial Advertiser (1773–1986)

» The Detroit News (1873–Present)

» Harper's Weekly (1857–1916)

» Hartford Evening Press (Connecticut, 1856–1868)

» Hickman Daily Courier (Kentucky, 1859–Present)

» Frank Leslie's Weekly (1852–1922)

» National Police Gazette (1845–Present)

» Newark Daily Advertiser (1832–1904)

» New-York Daily Tribune (1842–1866)

» The New York Herald (1840–1920)

» New York Tribune (1866–1924)

» New York Semi-Weekly Tribune (1853–1866)

» The New York Times (1851–Present)

» Philadelphia Inquirer (1829–Present)

» Oregonian Weekly (1850–Present)

» Rochester Daily Union and Advertiser (1860–1885)

» Rochester Evening Express (1859–1882)

» Rutland Herald (1794–Present)

» The True Union (Baltimore, 1849–1861)

Southern News Publications

» Alexandria Gazette (Virginia, 1834–1974)

» Arkansas Gazette (1819–1991)

» Army & Navy Messenger (Petersburg, Virginia, 1863–186?)

» Charleston Daily Courier (1852–1873)

» The Charleston Mercury (1825–1868)

» The Chattanooga Gazette (1839–1866)

» The Weekly Southern Guardian (Columbia, South Carolina, 1857–1865)

» The Nashville Daily Press (1864–1865)

» Nashville Daily Times and True Union (1864–1865)

» The Galveston News (1842–1861)

» The Galveston Daily News (1865–Present)

» Galveston Tri-Weekly News (1863–1873)

» Galveston Weekly News (1845–1893)

» The Houston Daily Telegraph (1864–1866)

» The (Houston) Tri-Weekly Telegraph (1855–1870)

» The Louisville Daily Journal (1830–Present)

» The Mobile Daily Register (1849–1861)

» The Sunday Delta (New Orleans, 1855–1863)

» Opelousas Courier (Louisiana, 1852–1910)

» The Post and Courier (Charleston, South Carolina, 1803–Present)

» Republican Banner (Nashville, 1837–1875)

» Richmond Enquirer (1815–1867)

» The Southern Enterprise (Greenville, South Carolina, 1854–1870)

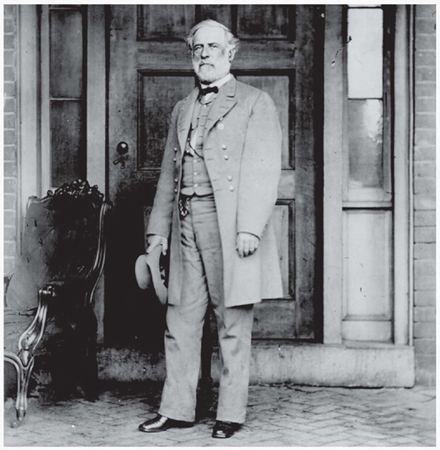

Mathew Brady, arguably the best-known Civil War photographer, took this portrait of Confederate Gen. Robert E.Lee days after Lee surrendered to U.S. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant in Virginia in April 1865.

Photography

Photography emerged as a significant new medium during the Civil War. Photographers followed in the wake of the armies and provided a visual record of units in the field, troops in camp, and the aftermath of battles. Photographers provided coverage of the war, its participants, and its effects that had not previously been possible.

Indeed, after the Battle of Antietam in September 1862, the Army of the Potomac held the field, allowing Northern cameramen to thoroughly photograph the aftermath of the encounter. And, in the days following the battle, photographers recorded Lincoln's visit to McClellan's headquarters and then followed the Union army across the Potomac and into recaptured Harpers Ferry, Virginia.

George N. Barnard served as official photographer of the Chief Engineer's Office. This photograph, taken outside of Atlanta in 1864, shows his equipment.

Notable Civil War-era photographers included William R. Pywell, Alexander Gardner (who photographed Richmond after it was destroyed by Federal troops), Timothy H.O'Sullivan (who accompanied the Union army in the western theater and recorded the course of its operations), and, perhaps most famous of all, Mathew Brady (who had employed both Gardner and O'Sullivan until 1863).

Beginning in 1845, Brady had made daguerreotypes of several famous Americans and published them in 1850 as The Gallery of Illustrious Americans. By 1860, he was making a good living through his three daguerreotype studios, two in New York City and one in Washington, DC.

War offered Brady new opportunities. At the expense of nearly his entire fortune, he outfitted a score of photographers with camera equipment and mobile darkrooms and sent them off to cover all fronts of the war. Contemporary equipment was too primitive to take action shots but the thousands of photographs they took depicted the war in a shocking, brutal way. Brady's name appeared on all of the photographs, in keeping with the convention of the day, something that has helped identify the work of his studios (for example, more than a third of the one hundred known photographs of Abraham Lincoln bear Brady's name).

Official military photographers, too, added to the pictorial archive of the war. For example, George N. Barnard, official photographer of the Chief Engineer's Office, created the best photographic record of the war in the West and made many pictures of Atlanta, Georgia, just prior to its destruction by fire upon Sherman's departure from the city.

Terms

ABATIS: An obstacle made from sharpened stakes or timbers, especially for blocking roads and impeding cavalry.

AMBROTYPE: An underexposed, negative photograph on a glass plate that appeared positive when set against a black background. Used primarily for portraits, glass photo plates had been invented in 1851 by Englishman Frederick Scott Archer.

BANQUETTE: A small mound of earth below the crest of a parapet that allowed shorter soldiers to fire over it more easily.

BARTON, CLARA: This “Angel of the Battlefield” played a significant role in providing medical care throughout the course of the Civil War. Her wartime activities included collecting and distributing supplies to soldiers, caring for the wounded, and gathering identification records for soldiers who were missing or dead. In 1881, she founded the American Red Cross, basing it to some extent on the Swiss-based International Red Cross.

BLUE MASS: A widely-used sort of medicine during the war that typically took the form of a blue or gray tablet and was used to treat disorders as diverse as tuberculosis, constipation, toothache, parasitic infestations, and birthing pains. Ingredients for one formulation included thirty-four parts rose honey, thirty-three parts mercury, twenty-five parts althaea, five parts licorice, and three parts glycerol, and most included the blue chalk or dye that gave it its namesake color. This term was also used, after the name of the medication, for the mass of men who would turn out for sick call.

CABLEGRAM: A telegram sent via undersea cable, a service that began to appear reliably in the late 1860s.

COTTON GIN: A device for removing seeds from cotton fiber. Devices for removing the seeds from long-staple cotton had long existed but were ineffective at removing seeds from the short-staple cotton of the Americas, a task that had traditionally been performed by slaves. In 1793, Eli Whitney invented a machine for removing the seeds from short-staple cotton. This device consisted of a boxed, revolving cylinder set with spiked teeth that could be turned by a crank, pulling the raw cotton through small slots and thereby separating the seeds from it. At the same time, a rotating brush operated pulleys, and a belt removed the cotton lint from the spikes. Many variations on Whitney's design appeared over the following years, including horse-drawn and water-powered gins, which radically speeded up the ginning process and lowered production costs.

DAGUERREOTYPE: Invented by Frenchman Louis Daguerre in 1837, this first practical means of photographic reproduction created detailed images on silver-plated copper sheets. Although popular, this process was also expensive and time-consuming, and was soon replaced.

DIPLEX: An innovation that allowed two telegraph signals to be transmitted simultaneously in the same direction.

DUPLEX: An improvement in telegraphy that allowed signals to be simultaneously transmitted from opposite directions over the same line.

FASCINES: Bundles of branches or saplings used to line earthworks or trenches.

FERROTYPE: See tintype.

FIRESTEP: See banquette.

FIRING PIT: A shallow pit dug out by hand and used to protect one or more infantrymen in combat. Veteran soldiers learned to begin digging such defense works whenever they stopped for an extended period of time and then continued to improve upon them as time and resources allowed.

“LAUDABLE PUS”: A term used by nineteenth-century doctors to describe the pus that formed in a wound after surgery or amputation and thought to be a beneficial sign of healing. In actuality, of course, it was a sign of massive bacterial infection, which often proved fatal.

OPERATOR: Since the 1840s, a telegraph operator.

PLANK ROAD: A road wide enough for two wagons, one side of which was dirt and the other side of which was covered with thick wooden planks. Conventions of the day dictated that heavily-laden wagons had right-of-way on the plank-covered side and that less full wagons should move on to the dirt side. As with other dirt roads, the parts not covered with timbers often became mud tracks in wet weather.

QUADRUPLEX: A combination of diplex and duplex technology that allowed a total of four messages, two coming from each direction, to be sent simultaneously along a single telegraph line and invented by Thomas Edison in 1874.

SWITCHBOARD: An term used in the 1860s to describe telegraphy routing equipment.

TAKE AN IMAGE: A period term that meant to have a photograph taken.

TELEGRAM: A term that came into use about 1850 to describe a message sent by telegraph. Prior to this, such messages had been variously called telegraphic dispatches, telegraphic communications, and telegraph messages.

TELEPHONE: Until being applied to Alexander Graham Bell's invention in the 1870s, this referred to a kind of non-electronic megaphone used for carrying music or voices over a distance.

TINTYPE: A photograph made by exposing a thin, blackenameled metal plate coated with a chemical compound called collodion. Small tintypes were the most common and inexpensive form of portraiture prior to the Civil War.

TRENCHES: Narrow, deep holes excavated to protect infantrymen. Ideally, a trench would be deep enough so a man could stand erect within it and still not be exposed to enemy fire. To fire from within a trench, a soldier would step up onto a one- to two-foot high parapet called a firestep. Civil War trenchworks, especially around besieged cities, often stretched for several miles, anticipating the style of warfare now most often associated with World War I.