2

WHERE PEOPLE LIVED: LIFE IN CITY, TOWN, AND COUNTRY

“Throughout the ages, big cities have fascinated people because they concentrate many ways of life, displaying splendor and misery on a stage for the entire world. In nineteenth century America, the drama of the scene increased when intensified urbanization and rapid industrialization exposed people to modern life.” — Gunther Barth, City People

America was not a widely urbanized country at the time of the Civil War but, as a result of the Industrial Revolution, its cities were multiplying and expanding. In the decades after the war, technology advanced rapidly, allowing farms to be tended by fewer people and creating more factory jobs in urban areas. These factors caused the nation to move toward becoming an urban, rather than a rural, society.

Where People Lived in the North

Northern society was more urbanized than the South in the middle of the nineteenth century. Virtually all of the nation's largest cities were located in the North, including the three largest, Chicago, New York, and Philadelphia, along with Boston, Cincinnati, Baltimore, and St. Louis (although the latter two were in “border states” with populaces that had significant pro-Southern sympathies). Some 5.5 million Northerners were city dwellers, about a quarter of the 22 million people living in the Union states. Most of the balance, about 16.5 million people, lived in towns or villages or on farms.

Where People Lived in the South

Southern society was far less urbanized than in the North, and only about 10 percent of the population, less than a million people, lived in cities, while the balance, just over eight million, lived in small towns and villages and on plantations and farms.

Southern cities, such as Charleston, New Orleans, and Richmond, tended to be smaller, less industrialized, and less congested than urban areas in the North.

Country Life

At the onset of the Civil War, rural people lived on farms as well as in small communities such as plantations, villages, and communes.

In 1860, the average American farm was about sixty acres in size and about a half mile away from a neighboring farm. This distance varied widely by region; farms in the West tended to be farther away from each other than farms in the East, and in newly-settled states or the territories it was often possible to go many miles without encountering any sort of homestead.

People settled in the new states and territories for a wide variety of reasons, often because land was cheap and plentiful. While many settlers embraced the isolation of rural life, many others suffered from loneliness, and periodic social events with their neighbors became very important. Another way people tried to off set the solitude and isolation of rural life in the nineteenth century, especially in the decades after the Civil War, was through the foundation of small villages, sometimes referred to as “rural neighborhoods.”

Farmhouses

Far too many regional and economic differences allow for a brief description of a “typical” nineteenth-century farmhouse but there are a number of general characteristics that could be found in many of them.

For one thing, because air conditioning had not yet been invented, houses were generally constructed with lots of windows and narrow rooms to encourage air circulation. For the same reason, many houses also included summer kitchens in outbuildings or well-ventilated areas separate from the main house, in order to keep the home and main kitchen from getting too hot during the summer months.

FARMHOUSE FEATURES

A Nineteenth century farmhouse often included these features:

» wooden construction

» narrow rooms and lots of windows (for good air circulation)

» multiple exterior doors (for air circulation and to serve as emergency fire exits)

» a summer kitchen

» a root cellar

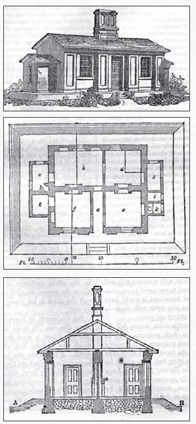

Godey's Lady's Book was famous for house plans. This is a modest cottage.

Houses were also generally constructed with several exterior doors, and even a modest home might have one door on each side. One reason for this was because, as with ample windows, a number of doors helped facilitate good ventilation. Just as important, however, was that wooden houses were prone to catching fire and people wanted plenty of ways to get out of them. While there were fire departments in some cities at this point in time, country folk were on their own if faced with such a calamity.

Many houses were also built with root cellars, which were used primarily for storing the vegetables that families would eat during the winter.

The most large and prosperous of such dwellings generally included a ground-level bedroom that functioned as a “birthing room” when necessary but was otherwise rented to travelers for the night. Such rooms tended to be far more popular than village inns, which were often much less clean or hospitable.

Villages and Towns

Mid-ninteenth century American towns were as diverse as the people who lived in them. Their style and atmosphere ranged from neat, orderly, prosperous communities in the farm country of the West, to raw, vital boomtowns in frontier areas, to sleepy, decaying former state capitals such as Williamsburg, Virginia. The average number of people living in a town ranged from several hundred to a few thousand. Such communities often served as a center of commerce for outlying farms and smaller villages.

Town streets and sidewalks were generally not paved, nor were there streetlights. Buildings visitors were likely to find included residences, inns, taverns, general stores, churches, cemeteries, tradesmen's workshops, doctors' and lawyers' offices, or pharmacists' shops, as well as public areas where people could meet, such as town greens or commons and market squares.

Other possible features of small communities included militia armories, warehouses (especially in port or rail towns), theaters (not cinemas), hospitals or sanitariums, and town, county, or district courthouses. Also, most towns had some sort of school or educational center, and some had several (for example, Williamsburg, Virginia, had nine private schools and colleges). While there were not likely to be any public parks, there tended to be considerably more shade trees than in contemporary cities.

Facilities not likely to be present in many towns during or immediately after the Civil War included banks, telegraph offices, and railway stations (unless the town had deliberately been built along a rail line).

AROUND TOWN

At the start of the Civil War, many villages and towns included:

» inns and taverns

» general stores

» churches and cemeteries

» tradesmen's workshops

» lawyers' and doctors' offices

» pharmacists' shops

» public space such as a square or green

Leading citizens of the town generally included gentleman farmers, doctors, lawyers, and the most prosperous merchants. Other typical inhabitants included laborers, slaves, servants, lesser merchants, tavern owners, tradesmen, and innkeepers.

Most plantations had a labor force of fewer than fifty black slaves. About half of all enslaved Southern blacks were “plantation negroes.”

In areas heavily contested during the war, many towns changed hands between Federal and Confederate forces several times over the course of the hostilities, having a profound effect upon the lives of the residents of those communities. When soldiers of the same side took control of the town, the inhabitants cheered them, opened their houses to the soldiers, and provided them with food and other amenities, or even returned if they had previously fled. When enemy soldiers took control, people sometimes fled, shut up their houses, hid their food or valuables, and generally avoided the invaders as much as possible.

Plantations

Plantations, one of the most characteristic institutions of the antebellum South, were large-scale agricultural ventures overseen by an owner or managers who used large slave-labor forces to produce cash crops for export. Plantations in America originated in Virginia and soon spread elsewhere, mainly to the South and West.

Plantations shared many aspects of villages, the main differences being that they were generally owned by a single individual, family, or organization and that the land around them were worked not by free white farmers but instead by black slaves. Many plantations even looked like villages. Besides a main house, plantations included buildings such as slave quarters, barns, stables, storage buildings, mills, workshops, and anything else they required. A plantation's occupants included the master and his family; overseers, who were sometimes cousins or other relatives of the owners; and a labor force of black slaves, up to several hundred on the largest plantations but fewer than fifty on most.

Many Southern plantations specialized in a single crop, usually cotton, rice, sugarcane, corn, or tobacco, as dictated by regional conditions. Cotton and sugarcane were the primary crops along the lower Mississippi River. South Carolina lead the country in rice production at the time of the war.

“During the summer months, rice crops waved over fields of thousands of acres in extent, and upon a surface so level and unbroken, that in casting one's eye up and down the [Santee] river, there was not for miles, an intervening object to obstruct the sight,” one visitor wrote in The American Monthly Magazine in 1836, revealing the intense level of agriculture the plantation system allowed.

Plantation owners reaped the rewards of this system and were often able to use their wealth to build large houses, lead extravagant lifestyles, and dominate the economic, social, and political life of the antebellum South. This wealth and power was acquired, of course, at the expense of others, and about half of all enslaved Southern blacks were “plantation negroes.”

In addition to planting and harvesting crops, plantation slaves were required to do many other activities. These included clearing land, cutting and hauling wood, digging ditches, slaughtering livestock, and repairing tools and buildings. Some slaves were taught other trades or skills needed on the plantation and served as carpenters, blacksmiths, machinists, drivers, and in other capacities. Inside the plantation house, slaves served as maids, butlers, cooks, nannies, wet nurses, and in all the other roles needed to run a large household.

America's plantation system was dealt a mortal blow by the Civil War, which ended slavery. After the war, plantation owners tried to maintain their way of life by using the sharecropping and tenancy systems to exploit free but impoverished blacks and whites alike. Eventually, however, machinery replaced mass labor and ended the viability of plantations as they had existed.

Communes

In the latter part of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, various religious groups and intellectual movements in America had established and lived in communal villages, where they practiced farming and sometimes other industries. Most of the early communes were founded by conservative Christian sects, such as Mennonites, Moravians, and Shakers.

Prior to the invention of the elevator, buildings could not practically be more than five or six stories tall and, as a result, the skylines of American cities were much lower during the war than they were by the end of the century. In 1857, Elisha Graves Otis introduced the first passenger elevator.

One of the most notable examples was the Amana Society, a conservative, pacifistic religious community that held all property in common. In 1842, some eight hundred members of the Amana group migrated to the United States from Germany. They settled initially in Ebenezer, New York, but eventually moved on to Iowa. The community still exists today and is known for making kitchen appliances.

Another good example are the Shakers, who established a small community at Watervliet, New York, in 1776. By 1830, some six thousand Shakers lived in communities in eight states. Shaker communes were marked by industry and became noted for manufacturing high-quality furniture. Unlike many other contemporary religious communes, the Shakers did not shun technology, and were noted for their technological innovations.

After the first quarter of the century and into the decades following the Civil War, various other groups founded communes throughout the country, including socialists, anarchists, Hutterites, Bohemians, Christian socialists, Theosophists, and Jews. A notable example is Robert Owen's utopian New Harmony commune in Indiana, which he founded in 1825.

Most communes lasted only a few years and then dissolved, especially in the years following the Civil War, when revivalism declined. Those based on conservative religious principles tended to enjoy the most longevity.

City Life

In the years leading up to the Civil War, increasing numbers of Americans and immigrants were being drawn to the large cities for the financial and social benefits they offered.

In the North, drafts were one of the war's most profound effects upon city dwellers. Industry, however, flourished, providing jobs for increasing numbers of immigrants.

In the South and border regions, where several cities were occupied by Federal troops (including Baltimore, New Orleans, and Charleston) or almost completely destroyed (as were Atlanta and Richmond), the war was felt much more directly. Destruction and occupation created a refugee problem, making it difficult to find adequate living space in many Southern cities. In one case, for example, six Southern families shared an eight-room house for two and one-half years.

Characteristics of Cities

American cities were generally divided up by function, into areas for industry and manufacturing; shopping, business, and entertainment; worship; education; and living.

With very few exceptions, American cities did not have any central organization. They were generally laid out on a rigid “gridiron” of city blocks, which usually did not take the natural geography in to account. These squares were further divided into lots that were owned by businesses, individuals, and other interests.

This lack of central planning was in striking contrast to most major European cities. However, Europe was a land of kings, emperors, strong central governments, and limited personal freedoms. While there were limitations, American landowners had an amazing amount of freedom in what they could do with their land. And, for the most part, the government was not empowered to direct the development of urban areas. According to Gunther Barth, author of City People, Americans “recognized neither prince, priest, nor planner as guide,” even though many were subsequently “dismayed by the chaotic scenes that the free use of space produced.”

A few American cities, built for specific purposes, did come into being as the result of central planning. These included Savannah, Georgia, founded in 1733 by James Oglethorpe as a mercantile and shipping center; Washington, D.C., selected by George Washington as the site of the nation's capital in 1790 and the seat of the Federal government since 1800; and Salt Lake City, Utah, founded in 1847 by Brigham Young and the Mormon church as the seat of their religion.

Prior to the invention of the elevator, buildings could not practically be more than five or six stories tall and, as a result, the skylines of American cities were much lower than they were by the end of the century. In 1857, Elisha Graves Otis introduced the first passenger elevator and, by the late 1870s, his sons had developed a hydraulic elevator with a speed of eight hundred feet per minute (a working electric elevator was introduced in 1889). Such devices encouraged the construction of much taller buildings than ever before.

If their families did not live nearby, young and single middle- and working-class people tended to rent rooms from families who had extra space. Maiden aunts, grandparents, and orphaned nieces and nephews were far more likely to live with relatives, if possible, than on their own or as wards of the state.

The first skyscrapers were built in the years following the Civil War and included the New York Tribune Building in New York City, completed in 1875 and designed by architect Richard Morris Hunt. It was Chicago, however, that became most closely associated with skyscrapers in the decades following the Civil War.

By 1870, Chicago had a population of nearly 300,000 and had become a major American center of commerce. In October 1871, a fire broke out in a barn and quickly spread out of control, destroying a third of the city in two days. Because of elevators, architects no longer faced the same height limitations on the building designs, and a new “Chicago school of architecture” was created as designers moved toward rebuilding the city with structures that reached skyward. By 1890, the city was full of nine-and ten-story buildings.

Transportation

In the middle of the nineteenth century, the disparate areas of the city, along with its suburbs, were increasingly linked with various forms of transportation. Streetcars and horse-drawn omnibuses were among the most common forms of public transportation prevalent along major downtown streets. Horsecars were an important means of linking the cities with the middle-class suburbs, particularly in the decades immediately following the Civil War.

Areas of the city often developed in response to the sort of transportation accessible from it. This is especially true of industrial areas. Warehouse districts, for example, grew up near railway terminals, and factories were built in the corridors along railway lines.

Residential Areas

Residential areas, or neighborhoods, were divided up like everything else in the city, in their case along class lines. Living conditions between upper-, middle-, and lower- and working-class peoples were much more striking in cities than in small towns or the country, and the various classes of society reacted to the expansion of urban areas in different ways.

At the time of the Civil War, more than half a million people lived in tenements in New York City alone, reaching a population density of 290,000 to the square mile in some areas.

Wealthy families either lived in affluent enclaves in or near the city center, or moved out of the city altogether to estates accessible by the main rail lines. Middle -class people became unable to afford houses within the city and increasingly left to live in small houses in the growing suburbs accessible by streetcars or railroads or, less often in the mid-nineteenth century, rented apartments. And the poor, who could neither afford property within the city nor afford to commute from the suburbs for their menial jobs in workshops, factories, and industrial areas, lived increasingly in subdivided tenant houses and tenements.

Upper-Class Neighborhoods

The richest people lived in large houses or mansions, often built in the newest architectural styles, such as Gothic Revival and Greek Revival (see Architectural Styles on page 56), and surrounded by sweeping lawns, gardens, and outbuildings, such as carriage houses. Their exclusive neighborhoods were characterized by broad, well-lit streets, Parisian-style parks, and features like art museums. Such neighborhoods, however, represented a distinct minority and were vastly outnum-bered by lower-class living areas.

Middle-Class Neighborhoods

Middle-class families tended to live in rowhouses, freestanding wood-frame houses or, less often in the 1860s, in apartments (generally known in mid-nineteenth-century America as “French Flats”). The size and stylishness of such homes varied widely depending on the incomes of their occupants; the families of prosperous merchants might live in attractive brownstone rowhouses, while those of clerks tended to live on long streets of small, identical homes with tiny front yards.

Young and single middle- and working-class people did not live alone as frequently during the 1860s as they do today. If their families did not live nearby, they tended to rent rooms from families who had extra space. Likewise, in an era of extended families, maiden aunts, grandparents, and orphaned nieces and nephews were far more likely to live with relatives, if possible, than on their own or as wards of the state. And, in contemporary cities, a majority of homeowners with spare rooms would rent them out to single boarders, often in conjunction with board or an arrangement to share common areas, such as a kitchen or parlor.

Lower- and Working-Class Neighborhoods

The poorest strata of society, which comprised about half the people in many cities, lived either in small, shabby wood-frame houses or, increasingly, in tenant houses and tenements. Working-class people in planned industrial communities, such as Lowell, Massachusetts, also lived in company-owned boarding houses, dormitories, and rowhouses.

“The first tenement New York knew bore the mark of Cain from its birth,” wrote journalist Jacob August Riis in 1890 of the once-fashionable houses along the East River that were subdivided into tenant rooms in the first decades of the century. The large rooms of these dwellings were divided into numerous smaller rooms, the rate of rent being determined by the size of the partitioned space. The higher it was above the street, the lower the rent.

Racing was America's most popular spectator sport prior to the rise of professional baseball, and tracks had existed since before the Civil War.

Specially-built tenant buildings, even worse than subdivided houses, were wooden structures two to four stories high built behind houses in spaces once used for gardens. Such rear tenant houses were often unsound and subject to collapse or fire. Often, more rental space was realized by the upward expansion of the front houses, although, in the words of a contemporary observer, adding such levels “often carried [the building] up to a great height without regard to the strength of the foundation walls.”

Tenements were the worst of the dwellings available to the poor. Distinct from any other sort of housing, tenements were often warrens of tiny spaces partitioned from huge abandoned hulks, such as churches or warehouses, or from entire city blocks. A description of the tenement from a nineteenth-century court case cited by Riis in How the Other Half Lives captures its spirit all too well.

“It is generally a brick building from four to six stories high on the street, frequently with a store on the first floor, which, when used for the sale of liquor, has a side opening for the benefits of the inmates and to evade the Sunday law,” the brief states. “Four families occupy each floor, and a set of rooms consists of one or two dark closets, used as bedrooms, with a living room twelve feet by ten. The staircase is too often a dark well in the center of the house, and no direct through ventilation is possible, each family being separated from the other by partitions. Frequently, the rear of the lot is occupied by another building of three stories high with two families on a floor.”

At the time of the Civil War, more than half a million people lived in tenements in New York City alone, reaching a population density of 290,000 to the square mile in some areas. There were numerous examples of tenement houses in which were lodged several hundred people with barely two square yards of living space each.

Most of the people who lived under such squalid conditions were recent immigrants, largely Irish, Italians, Scandinavians, Germans, and Dutch. Most of them were industrious people who lived in tenement conditions because of their desire to work, which they could do only if they lived in the city; in the absence of automobiles or public transportation into the suburbs, people were unable to live outside of the city and commute into work, as so many do today.

Rent for tenements was usually paid a month in advance. Ironically, the cost of renting such miserable rooms was often 30 or 40 percent higher than it would be to rent small, clean, country cottages. However, jobs for the masses were available only in the cities, so people were forced to pay extortionate rates to live under wretched conditions. De facto slavery, then, was a fact of life in the North as well as the South. In light of this, it is more comprehensible, while no less tragic, that Irish laborers rioting in the summer of 1863 took out their anger against blacks, whom they saw as beneficiaries of the war against the South.

Death was a daily fact for people in the worst tenement districts. Infant mortality rates were as high as one in ten in some areas (i.e., considerably worse than many developing countries today). Suicide was also not uncommon. One sad episode involved a young immigrant couple who occupied a room less than ten feet by ten feet; they drank poison together rather than continue their dreary existence. And disease, which often left upper-class districts of the city untouched, could kill nearly 20 percent of the people in the most congested areas. In New York City, the general mortality rate for the city as a whole was 1 in 41.83 in 1815. With the rise of the tenement, this general rate rose to 1 in 27.33 in 1855.

Pigs, the most common urban scavengers, were among the hazards people had to deal with in the worst parts of the city. Such beasts could be aggressive and dangerous, especially to women and children, and their presence persisted on New York City streets until the winter of 1867, when city ordinances were passed prohibiting them from being allowed to roam in built-up areas.

Urban Recreation Areas

As urban areas expanded in the early and mid-nineteenth century — and as property values increased — green spaces within cities shrank and disappeared. As a result of this, city dwellers began to crave areas reminiscent of the country. This, in conjunction with a variety of other factors, led to the rise of public parks.

Unfortunately, people's use of public parks for leisure activities took a toll upon the grass, trees, and other plants. This led to officials spending an inordinate amount of time and energy in preventing people from actually using, and thus damaging, public parks. To a great extent, this diminished the value of parks to many city dwellers.

In the absence of parks, cemeteries became popular places for people to meet and walk. Venues for spectator sports that included green areas, such as racetracks and baseball parks, were also very popular with city dwellers, certainly to some extent because of their appearance, as well as for what they were used for. Racing was America's most popular spectator sport prior to the rise of professional baseball, and tracks had existed since before the Civil War. And, while baseball had been growing in popularity since the 1840s, it was usually played in parks, fields, and empty lots until after the Civil War, when specialized parks began to be built for the sport.

City Water and Sewage Systems

Indoor plumbing depended on municipal water systems, something that had only come into existence in America a few decades before the Civil War and was still not widespread by 1861. Crowding in urban areas, however, spurred by the Industrial Revolution, had necessitated development of city water and sewage systems.

While most urban areas were equipped with storm drains, disposal of human waste into them had generally been prohibited, but as city populations swelled, it became more and more difficult to prevent the drains from being abused in this way. In the absence of adequate means for providing fresh water and carrying away filth, sewage flowed into lakes, rivers, and tidal estuaries. The bodies of water and shallow wells from which people drew their drinking water became heavily contaminated with disease-bearing organisms.

Waterborne diseases like cholera spread unchecked in some cities. In the years following the Civil War, one particularly savage outbreak in Chicago, caused by sewage accidentally flowing into the water system, killed a quarter of the population, some 75,000 people. Chicago responded by developing one of the most advanced water systems in the country, and the threat of such out-breaks prompted administrators in other cities to create adequate water supply systems.

URBAN WATER WORKS In the early 1800s, the invention of the steam engine meant that pumps could be used for maintaining water pressure in city water supply systems. In 1820, Philadelphia was the first American city to finish building municipal water works and, in 1823, Boston completed the first American sewer system.

New York City provides an excellent example of an early water supply and transmission system. Begun in 1830 with the construction of the Croton Reservoir — an impoundment of the Croton River that was completed in 1842 — the system conveyed water to the city through a massive system of gravity tunnels that were long considered one of America's greatest engineering feats.

Water filtration systems were first installed in America in Poughkeepsie, New York, in the 1870s (although even by 1900, only ten filtration plants were in operation throughout the entire country).

TOILETS AND THE LIKE Prior to the existence of plumbing, people had generally used out-houses. An outhouse was known as such in the mid-nineteenth century, and might also be called a “privy,” “privy house,” “jake,” “joe” or “john” by rural or lower-class people, and as a “house of office,” “necessary house” or “necessary” in more polite society. When separate outhouses were available for men and women, the door to the men's was often marked with a sun and the women's with a crescent moon.

Many middle class Americans lived in small wood-frame houses or cottages.

Chamber pots were also kept indoors, usually under the bed, for use at night, by the sick, or in case of emergencies. Other common names for these implements included “piss pot” and “potty” (for a small chamber pot, as for one used by a child). In the homes of affluent people, a chamber pot was sometimes embellished to look like something else and was referred to as a “commode” or a “chaise perce.”

In the mid-1700s, privies began to appear inside of upper-class homes. Initially, these were little more than small rooms containing a chair with a hole in the seat and a chamber pot beneath it (which still had to be emptied, of course). Such a privy was referred to as a “water closet,” “closet stool,” or “close stool.” Actual toilets, sometimes called “quinces,” did not come into use until the 1820s, and only then in areas where municipal sewage existed. Toilet covers followed by the late 1830s. By the 1850s, urinals were being used by men in urban areas.

Toilet paper did not become available until the 1880s. Prior to that, people used materials like leaves, corn shuckings, and old newspapers.

BATHING By the 1830s, many Americans were bathing on a weekly basis, generally on Saturday night so they would be clean for Sunday services. This was a radical departure from even a generation earlier, when it was only the wealthy or the eccentric who bathed regularly. A generation before that, bathing had been considered immodest, uncomfortable, and unnecessary, and many people went their entire lives without ever bathing.

In the 1830s, people generally bathed in large wood or tin tubs in front of a fireplace or kitchen stove where water could easily be heated. During this period, the term “bathroom” was used to refer to a room used only for bathing and which did not contain a toilet, as today.

By the mid-1850s, the homes of some affluent people included bathrooms in the modern sense, with both a bathtub and a toilet (one of the first was installed in 1855 in the New York City mansion of George Vanderbilt).

The trend toward bathing more frequently continued after the end of the Civil War. In 1865, Vassar College made it mandatory for girls to bathe twice a week. By the 1880s, an estimated 15 percent of all American city folk had indoor bathrooms of some sort.

Architectural Styles

Several distinct styles of architecture predominated in America during the 1860s and could be found in the country's homes, churches, government buildings, memorials, and other structures. Naturally, some of these styles persisted from earlier decades (e.g., Georgian), as homes and public buildings were not torn down and replaced just because new styles developed.

As a loose rule, the styles that predominated in the eighteenth century had their origins in England and those that developed during the nineteenth century were characterized by Romantic revivals and eclecticism.

In the years leading up to, during, and following the Civil War, the Georgian, Neoclassic, Greek Revival, Corporate, Egyptian Revival, Italianate, Second Empire Baroque, High Victorian Gothic, and Richardsonian Romanesque were all major influences on American architecture. These styles are further described below, along with a few examples of each (mostly public buildings, with which people are more likely to be familiar).

Georgian

Georgian (1714–1776) was an English-inspired style of architecture that predominated in America until the Revolution. Named for England's King George I, who ascended the throne in 1714, this style of architecture showed a greater concern for style and higher standards of comfort than earlier styles. Georgian architecture, however, carried the taint of British imperialism and colonialism, and it was abandoned after independence was achieved. Georgian-style buildings proliferated throughout the New England and the Southern colonies, and good examples include the Old North Church (1723) and the Old State House (1712), both in Boston.

Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (1750–1850), influenced heavily by Thomas Jefferson, supplanted Georgian architecture in America and came to represent the political and social identity of the new nation. It included several variations, including Federalist, Idealist, Rationalist, and Greek Revival.

FEDERALIST architecture, heavily influenced by English models, was especially prevalent in New England and was used for many official structures. A good example is the State House in Boston (1795–1798), designed by architect Charles Bulfinch.

IDEALIST architecture was an intellectual and moral approach to classicism that was at first inspired by Roman models. Symbolism played an important role in this style, an excellent example of which is Thomas Jefferson's Monticello (1770–1809) in Charlottesville, Virginia.

RATIONALIST architecture emphasized classical structure and building techniques, such as stone vaulting and domes.

GREEK REVIVAL became the first truly national American style of architecture and, being very adaptable, appeared in all sorts of buildings, public and private, throughout every part of the country. One reason this style became so popular was that it was strongly associated with classical traditions and democracy, making it ideal for the buildings of a young republic. Examples include the Ohio State Capitol, Columbus, Ohio (1838–1861), designed predominantly by painter Thomas Cole; and the Treasury Building, in Washington, D.C. (1839–1869), designed by architect Robert Mills. This style was also used for many mansions and Southern plantation houses.

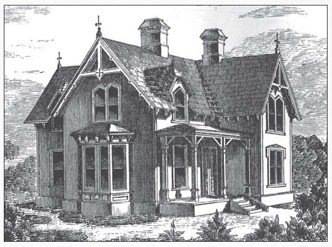

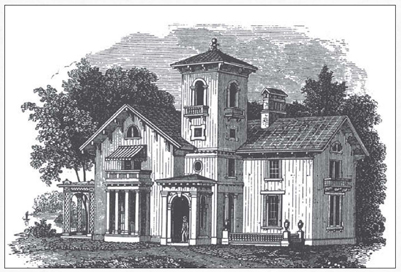

Italianate-style villas were popular as both country and city residences for well-to-do families.

Corporate

Corporate (1800–1900) architecture was a practical style used for commercial and industrial structures, especially factories, and, in its time, was considered to be a “style-less style.”

Egyptian Revival

Egyptian Revival (1820–1850) was used primarily for memorials, cemeteries, prisons, and, later, warehouses. The most famous American example of this architectural style is the Washington Monument, an Egyptian-style obelisk.

Gothic Revival

Gothic Revival (1820–1860) architecture, based on English and French styles of the twelfth to fifteenth centuries, was strongly associated with religion and nature and was used for both ecclesiastic and residential structures, from urban churches to rural cottages. Good examples include St. Patrick's Cathedral (1858–1879) in New York City, designed by architect James Renwick, and the “wedding cake” house, built around 1850 in Kennebunkport, Maine.

Italianate

Italianate (1840–1860), or Italian Villa Mode, was an architectural style inspired by Renaissance models that was used for domestic structures, notably country houses and villas.

Large, well-built farmhouses were evidence of the prosperity of many American farmers both before and after the Civil War.

Second Empire Baroque

Second Empire Baroque (1860–1880) originated in France and was largely influenced by the additions to the Louvre in the 1850s and the construction of the Paris Opera. In America, this style was used for both public and residential structures. Good examples include the State, Navy, and War Building in Washington, D.C., designed by architect Alfred B. Mullet, and City Hall in Philadelphia (1868–1901), designed by architect John MacArthur.

High Victorian Gothic

High Victorian Gothic (1860–1880), which originated in England and was named for Queen Victoria I, was used for public, religious, and residential buildings. Good examples include the Pennsylvania Academy of Art (1876), in Philadelphia, designed by architect Frank Furness, and the First Church (1868) in Boston, designed by architects William Ware and Henry Van Brunt.

Richardsonian Romanesque

Richardsonian Romanesque (1870–1895), named for designer Henry Hobson Richardson, was a revival style based on French and Spanish Romanesque styles of the eleventh century. Structures built in this style are somber and dignified and characterized by massive stone walls, dramatic semicircular arches, and a dynamism of interior space that was new at the time. Richardsonian Romanesque was the last major style to influence American architecture in the years immediately after the Civil War and eclipsed all others for a time. Good surviving examples are Grace Church (1867–1869) in Medford, Massachusetts, and Trinity Church in Boston (1872–1877), both designed by Richardson himself.

Costs of Homes and Housing

What it cost to buy a home or rent living space varied widely from city to country and from North to South during the Civil War. Following, however, are some examples of what it cost to buy or rent a home. Some of the costs for homes are from contemporary catalogs and publications, and editorials of the day sometimes derided them as being overpriced.

Housing

|

COST IN THE 1840S |

COST IN THE 1850S |

|

|

prairie-style farmhouse: |

$800 to $1,000 |

|

|

large but modest farmhouse |

$2,000 to $3,000 |

|

|

larger, nicer farmhouse |

$3,000 to $6,000 |

|

|

large, extravagant country house |

$3,000 to $14,000 |

Rent

|

COST |

|

|

house |

$500 per year (In areas affected by wartime housing shortages, this price was at least doubled.) |

|

room and board in a boarding house |

$30 to $40 per month (1862). |

|

furnished house |

$80 per month (1863) |

|

third-story front room, without carpeting or gas for heat or light |

$60 per month (1863) |

|

sleeping/dining room, plus use of parlor |

$60 per month plus one-half the gas bill (1863) |

|

room and board in a rooming house |

$50 or more per month (1863) |

|

furnished rooms |

$25 to $110 per room, per month (1864) |

|

Rooms in a tenement for a family (in a rear building divided up for ten families, worth $800 altogether) |

$5 per month |

|

Stable, rented as a dwelling (one of twenty on a fifty foot by sixty foot lot, worth $600 altogether) |

$15 per year |

Terms

INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION: The shift from an agrarian into an industrial society that began in America at the end of the eighteenth century and continued throughout the nineteenth century. A central aspect of the revolution was a radical increase in per capita production, facilitated by the mechanization of manufacturing.

JAKE, JOE, JOHN: Slang terms used primarily by men to refer to either outhouses or chamber pots.

QUINCY: slang term for a toilet that originated in 1825, when a toilet was first installed in the White House during the presidency of John Quincy Adams, an event that prompted much debate and many jokes.