3

EDUCATION: FROM SCHOOLHOUSES TO UNIVERSITIES

“Education is that which discloses to the wise and disguises from the foolish their lack of understanding.” — Ambrose Bierce

While opportunities for education of various sorts were widespread throughout the United States during the era of the Civil War, they were by no means uniformly available or of the same quality from region to region, nor were they available to people of all races or economic means. Many changes in education took place in the decades leading up to the conflict, and these changes impacted the people who lived during the war by shaping their knowledge base.

Most education, both public and private, was geared toward preparing an elite few for college. Curricula and educational materials were classical in nature and tended to stress the importance of morality and civic duty, and an ability to read and write in Greek and Latin was emphasized (although German and French predominated as acceptable second, modern languages).

The first schools in America were founded in the 1600s, the earliest in Massachusetts, starting in 1635 with the Boston Latin School and followed a year later by Harvard University. Within a few decades, all of the New England colonies had established some sort of mandatory education programs for boys, the emphasis generally being on grammar schools intended to prepare the sons of relatively affluent families for college. Educational prospects for girls or the sons of the less privileged were considerably more rare.

Teaching children was not a prestigious occupation in the early nineteenth century. Many teachers during this era were not especially well-qualified.

In the 1700s, “common schools,” began to appear throughout the country. These typically did not grade students in any way and, while they were generally supported by the community, were typically not free and charged some sort of tuition. And, while some public support for female education did exist in New England by 1767, such programs were optional and many communities were reluctant to underwrite either female schooling or institutions that would benefit poor families. In communities where everyone was taxed to support schools, desire to support them was generally limited while in communities that assessed school taxes only against those who had children, there was typically widespread support for programs that would benefit boys and girls of all social classes.

Various religious denominations founded most early American colleges for the purposes of training clergymen and, in New England in particular, literacy was a priority so that people would be able to read the Bible. Most of the institutions of higher education that began operating between 1640 and 1750 are members of what has since become known as the Ivy League (a term that did not come into widespread use until the 1950s), including Brown, Columbia, Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton, and Yale.

Education flourished in some quarters in the years following the American Revolution, especially in the North. Private academies sprung up in cities and towns across the country, and Americans overall had one of the highest rates of literacy in the world at the time of the Civil War. In rural areas, however — especially in the South — there were few schools established prior to the 1880s.

Teaching children was not a prestigious occupation in the early nineteenth century and many of the most educated people of the time were not interested in doing so, meaning that many teachers during this era were not especially well-qualified. Local school boards were responsible for verifying the credentials of the teachers they hired but, as often as not, the board's primary concerned was to not overspend tax dollars. Starting in 1823, however, with the foundation of the Columbian School in Concord, Vermont, an increasing number of two-year normal schools — institutions designed to train teachers to provide primary education — were established throughout the country. In the decades leading into and following the Civil War, a growing number of elementary-school teachers received training from such schools.

Starting in the late 1830s, particularly in the North, more private academies were established throughout the country for the purposes of educating girls beyond primary school, and some of these offered a classical curriculum similar to that provided for boys. Starting in 1840, the national census conducted once every ten years included questions related to education and literacy, and the responses indicated that of the 1.88million boys and 1.8 million girls between the ages of five and fifteen, somewhat more than half attended some sort of primary schools or academies.

One-room schoolhouses with one teacher were common in rural areas.

Nationwide, the school system was largely private and unorganized until two decades before the onset of the Civil War, when the Federal government began to play a larger role in education. However, public secondary schools did not begin to outnumber private academies until the beginning of the twentieth century.

Throughout the nineteenth century, one-room school-houses in which a single teacher provided all the primary and secondary education for the school were a phenomenon of rural areas that had low population densities but a high proportion of young people. Spread-out farming communities without central areas sometimes had anywhere from two to a half-dozen such facilities. Schools were placed so that children would not have to travel too far to attend them and so that children could be home in time to do their afternoon chores. Sessions at such schools were also most likely to be conducted in the cold-weather months, when students had less work on family-run farms.

In the five decades between the end of the Civil War and the beginning of World War I, the growth of urban areas, influx of foreign immigrants, and national spirit of reform all played a role in transforming the character of American education. More high schools were established and their curriculum was modified to prepare students for the expanding private and state colleges and universities. Education also began to shift away from a classical nature to more a vocational and utilitarian style.

Educational Movements

A number of educational movements occurred in the years leading up to, during, and after the Civil War that affected the education people received during the era. These included the establishment of common and normal schools throughout the country, the concept of “republican motherhood,” and the establishment of land-grant institutions.

Common and Normal Schools

In 1837, Horace Mann became secretary of education in Massachusetts and set about creating a statewide system of “normal schools” to train professional teachers. He also established “common schools” for primary and secondary education. Common schools were developed from a model used in Prussia that was based on the idea that everyone was entitled to a uniform education.

Mann postulated that universal public education was the best means of transforming the country's undisciplined youth into conscientious citizens of the republic, and his ideas were widely accepted by progressives and fellow Whigs.

Establishment of public common and normal schools in accordance with Mann's guidelines began to spread throughout the North, especially in New England, and most states eventually adopted something at least reminiscent of the system of schools he had established.

Republican Motherhood

In the early nineteenth century, a number of influential female writers in New England began proffering the idea that, as the people tasked with taking care of children, women were the best qualified to serve as their teachers. Especially popular in urban areas, this concept of “republican motherhood” was an early family-values movement that linked the success of the burgeoning nation with the virtue of its families.

By the 1840s, these apologists for republican motherhood had begun to successfully make the case that educational opportunities for women and girls should be expanded and improved and that they should be granted greater access to subjects previously offered only to males. Such subjects, including philosophy and mathematics, became increasingly essential elements in the curricula for girls at both public and private schools. In the years during and following the Civil War, such institutions were increasingly spreading and bolstering a growing tradition of women as the teachers and overseers of American ethical and moral values.

These ideas became widespread throughout the country and went a long way toward enhancing the status of women and convincing people of the need for girls to be educated so that they could become effective and virtuous teachers and mothers of good citizens.

While these ideas had their genesis in the North, they caught on in the South as well, and private female academies — made possible through donations and community spirit — were established in towns throughout the region. Plantation owners in particular were interested in educating their daughters, not least of all because a complete education could make them more marriageable and even serve as a substitute for dowry payments.

Such Southern female academies had a broad, structured curriculum that emphasized proficiency in writing, penmanship, arithmetic, and foreign languages. By the 1840s, these schools were producing a refined and literate body of women well-suited to serve as the wives and mothers of the upper crust of Southern society.

The “republican motherhood” movement promoted the idea that women were the best suited to teach.

Land-Grant Institutions

Passed by the U.S. Congress during the Civil War, the Land-Grant Colleges Act of 1862, also called the Morrill Act, provided federal funds for states to establish educational institutions that specialized in agriculture, engineering, and military studies. Such facilities were known as “land-grant” institutions.

Some of the first schools to be established under these provisions included Kansas State University (1863), Cornell University in New York (1865), the University of California (1868), Purdue University (1869) in Indiana, The Ohio State University (1870), and Texas A&M University (1871). Michigan State University and Pennsylvania State University were both founded as state land-grant schools ahead of the Morrill Act, in 1855.

Such schools were generally intended to bolster the declining importance of agrarian values in America. Another goal was to teach farmers more effective agricultural techniques, and students were often expected to cover part of their expenses and strengthen their character by performing agricultural labor. This requirement was increasingly dropped at land-grant institutions; many such schools did not have well-developed agricultural curricula anyway. In practice, few alumni became farmers. Instead they moved on to middle-class, white-collar occupations of various sort, which lead many contemporary politicians to criticize such schools as expensive and useless experiments.

Where the land-grant institutions proved their value, however, was in training the cadre of industrial engineers and agricultural scientists who, for the half-century following the Civil War, led the rapid expansion and industrialization of the country and its establishment as a technology-based world power.

Students attending land-grant universities were often expected to cover part of their expenses and build character by performing agricultural labor, but few alumni became farmers, instead moving on to middle-class, white-collar occupations.

Education in the North

Public primary education was fairly widespread in the Northern states, especially in urbanized areas. Many institutions of higher education had existed in these states since Colonial times, and new colleges continued to be established throughout the nineteenth century. As a result, Northerners enjoyed a relatively high level of education and literacy.

New England in particular was on the cutting edge of education for the country in general, and communities across both the North and the South adopted many of the improvements developed there in one form or another, as illustrated by Massachusetts' normal school and common school models.

A great number of educational institutions that were founded in the nineteenth century were subsequently renamed and expanded in the decades or century following their initial establishment, but their beginnings shaped the minds of the Civil War generation.

California

California's 1849 constitution called for free statewide public education. One of the first colleges established in the state was the Contra Costa Academy in Oakland in 1853, founded for purposes of training its students to establish a Christian college. They did so in 1855 with the foundation of the College of California, a private institution that was merged with the public Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College in 1868 to form the University of California, one of the country's earliest land-grant institutions (which, in 1873, was relocated from Oakland to Berkeley).

Other institutions of higher education in California included Santa Clara University, a private Jesuit school that is the oldest university in the state; the University of the Pacific, a private university that was affiliated with the United Methodist Church at the time of its establishment (1851); Mills College, an independent liberal arts women's college (1852); and the University of San Francisco, another private Jesuit university (1855).

Connecticut

Influenced to a great extent by its neighbor to the north, Connecticut adopted a system of normal and common school in 1849 similar to those established by Horace Mann in Massachusetts.

Historic institutions of higher education in the state include Yale University (1701), the American School for the Deaf (1817), Trinity College (1823), and Wesleyan University (1831). It was also home to Litchfield Law School, the country's first law school, which operated from 1773 to 1833.

Boarding schools operational during the era of the Civil War would have included Cheshire Academy (1794), Suffield Academy (1833), Miss Porter's School (1843), the Gunnery (1850), and Loomis Chaffee (1874).

Private day schools included Hopkins School in New Haven (1660), the Norwich Free Academy in Norwich (1854), and King Low Heywood Thomas in Stamford (1865).

Hartford Public High School (1638) is the second oldest secondary school in the United States and the Hopkins School (1660) is the fifth oldest.

Delaware

Delaware had established public primary and secondary education in 1829, but it was under-funded, uneven in quality, and excluded blacks.

The University of Delaware was chartered in 1833 and grew out of a Presbyterian “Free School” that had originally been founded some ninety years earlier during the Colonial era and was operated out of the home of minister Francis Alison (and had evolved into the Academy of Newark by 1769). Other institutions included the Wilmington Conference Academy (1873, renamed Wesley Collegiate Institute in 1918).

Illinois

Educational institutions active during the era of the Civil War in Illinois include private North-western University, founded in 1851 by nine Chicago businessmen to serve the people of what had just a generation before been the Northwest Territory; Illinois State University, the oldest public university in the state and the legal documents for which were drawn up by lawyer Abraham Lincoln; Illinois Industrial University, founded in 1867 as a land-grant school and the basis of what would eventually become the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, the second-oldest public university in the state; and Saint Ignatius College, a Jesuit institution founded in 1870 that became Loyola University Chicago.

Indiana

In 1816, the Indiana constitution was the first in the nation to establish a state-funded public school system, and it also allocated a township for development into a public university. These plans were too ambitious for a frontier society, however, and there was initially not enough of a tax base to support them. A new state constitution in 1851 included provisions for supporting such educational institutions and, while the development of a system of public schools was impeded by legal red tape, a number of elementary schools were open by 1870.

America's first free kindergarten, trade school, and coeducational teaching system were none-theless founded in New Harmony in the first half of the nineteenth century. In 1801, Jefferson Academy was founded and it subsequently became Vincennes University; the Indiana State Seminary was founded in 1820 and became the basis for Indiana University; the University of Notre Dame was founded as an all-male Catholic school in 1842; Taylor University was founded in 1846, the first evangelical Christian college in the country; Indiana Asbury University was founded in 1837 and went on to become DePauw University; Moores Hill College was founded in 1854 and subsequently became the University of Evansville; Butler University, one of the country's first higher education institutions to admit women, was opened in 1855; and Purdue University was established as a land-grant institution in 1869.

Iowa

One of the most significant educational institutions at the time of the Civil War was the Iowa Agricultural College and Model Farm, founded in 1858 in Ames, reclassified in 1864 as the nation's first land-grant institution, and eventually renamed Iowa State University of Science and Technology. Other public institutions included the University of Iowa, founded in 1847, and the University of Northern Iowa, founded in 1876.

Kansas

Kansas' first colleges were chartered by acts of the Kansas Territorial legislature and signed by the territorial governor in February 1858, and, of the ten institutes of higher education established at that time, three survive in some form. These include Baker University, the oldest continuously-operating college in the state; Highland University, now Highland Community College; and Blue Mont Central College, now Kansas State University. Other institutions of higher education included the University of Kansas (1866) and Emporia State University (1863).

Kansas' public universities were among the first in the nation to become coeducational, Kansas State University being the third and the University of Kansas (1869) the fifth.

Kentucky

Kentucky's first school opened in 1775, and a public school system was established by the state legislature in 1838. Higher education institutions included Transylvania Seminary, chartered in 1780 and the oldest university west of the Allegheny Mountains; the University of Louisville, founded in 1798; and the University of Kentucky, established in 1865 as a land-grant institution. It is also home to Berea College (1855), the first coeducational institution of higher learning in the South to admit both black and white students, which it did starting from when it was founded.

Maine

Maine had a well-established tradition of higher education by the time of the Civil War. Its public institutions of higher learning included Western State Normal School (1864), a teaching school that eventually became the University of Maine at Farmington, and the Maine College of Agriculture and the Mechanic Arts (1865), a land-grant institution that became the University of Maine.

Maine's private institutions of higher education included Bowdoin College (1794), Colby College (1813), Bangor Theological Seminary (1814), and Bates College (1855). One of the most famous Union heroes of the Civil War, Maj. Gen. Joshua Chamberlain, was a professor of rhetoric at Bowdoin when the war began, and he took a leave of absence from teaching to serve in the 20th Maine Volunteer Infantry Regiment.

Maryland

Jons Hopkins

Statewide education was established in Maryland in 1826 but excluded blacks because Maryland was a slave state. In 1867, a separate school system was established for black students.

The University of Maryland in Baltimore is the state's oldest public institution of higher learning and was founded in 1807. The Maryland Agricultural College was established in 1856, became a land-grant institution in 1864, and is today better known as the University of Maryland College Park. Southern sympathies were strong in Maryland throughout the war and, when Confederate troops briefly occupied this campus, it was noted how well its administrators got along with the invaders.

One of the most significant private institutions of higher education in the state is Johns Hopkins University (1876), founded with a grant from the Baltimore entrepreneur for whom it is named.

Massachusetts

Education at every level — from primary to university — had been important in Massachusetts since its earliest days, and the state was undoubtedly the leader in American schooling by the time of the Civil War; in 1642, the Massachusetts Bay Colony made “proper” education compulsory and nearly every system of teaching currently used in the United States originated in Massachusetts before or during the nineteenth century.

Boston Latin School, both the nation's first public secondary school and oldest-existing school in the United States, opened in 1635; Harvard, the first college, was founded in 1636; the Roxbury Latin School opened in Boston in 1645; Boston started the first public high school in the country in 1821; the first high school for girls was established in 1826; and the first public normal school in the nation, the Framingham Normal School, was founded in 1839.

Massachusetts passed a compulsory attendance law for primary and secondary education in 1852, ensuring that all children would receive at least some formal education.

Michigan

Public education had been important in Michigan since 1787, when the Northwest Ordinance called for the future state to “encourage education.” America's first state primary school fund was established in 1837, free primary schooling was made available in 1869, and in 1874 the state supreme court upheld the legality of using local taxes to pay for the establishment of high schools.

Public institutions of higher education during the era of the Civil War included the University of Michigan Ann Arbor (originally founded as the Catholepistemiad in Detroit in 1817, two decades before Michigan even became a state); Michigan State University (1855), a state land-grant institution; and Detroit Medical College (1868), the oldest part of what is now Wayne State University.

Private institutions at the time of the war included Grand Traverse College (1858), which later changed its name to Benzonia College and closed its doors in 1918 (and which was the alma mater of noted Civil War historian Bruce Catton).

Minnesota

In 1849, Minnesota's territorial government established provisions for school districts and declared that common schools were to be open to all people between the ages of four and twenty-one, supported by a general sales tax and part of the proceeds from fines and licenses. However, by the early 1850s, only about 250 children were enrolled in three privately-operated schools. In 1858, the state legislature established a normal school in Winona.

Public institutions of higher education during the era of the Civil War included the University of Minnesota, which was founded in 1851 but, because of financial problems and the onset of the Civil War, was unable to actually begin enrolling students until 1867.

Private institutions included Northfield College (1866), now known as Carleton College; Augsburg College (1869) in Minneapolis; and St. Olaf College (1874), also in Northfield.

Missouri

Before the Civil War, primary and secondary education in Missouri took place mainly in private institutions. In the years following the war, however, free public education became available in most parts of the state.

Higher education institutions included St. Louis University (1818), the University of Missouri (1839, the first state university west of the Mississippi), Washington University (1853), and Lincoln University (1866).

Nevada

Established by the state's constitution, the University of Nevada in is the oldest institution of higher learning in the state and was opened in 1874 in Elko as a land-grant university (and was eventually relocated to Reno).

New Hampshire

The first high schools in New Hampshire, the Boys' High School and the Girls' High School in Portsmouth, were established between 1827 and 1830.

Many colleges and universities existed in New Hampshire in the mid-nineteenth century, including Dartmouth College (founded in 1769) and the University of New Hampshire (1866, a land-grant institution).

America's first free public library, the Juvenile Library, was established in 1822 in Dublin, and the first free library supported by public funds was opened in Peterborough in 1833.

New Jersey

In 1871, statewide public education was established in New Jersey, and an 1875 amendment to the state constitution required that free public schooling be provided for all children between the ages of five and eighteen.

Public colleges in the state during the era of the war included the New Jersey State Normal School (1855), now the College of New Jersey, in Ewing Township; the Newark Normal School (1855), now Kean University; and Rutgers College (1825), originally established as Queen's College in 1766 and now known as Rutgers University.

Private institutions of higher learning established by the time of the Civil War included Princeton University (1746), one of nine colleges in the country founded prior to the American Revolution; Seton Hall University (1856), a Catholic institution in South Orange; and Rider University in Lawrenceville (1865).

New York

Since 1784, education in New York has been the responsibility of the sixteen regents of the University of the State of New York.

Institutions of higher learning included the Collegiate School (1628) in Manhattan; the U.S. Army Military Academy at West Point, founded in 1802 at the site of a military fortification over-looking the Hudson River; New York University, established in 1831; Fordham University, founded by Jesuits in 1841; and Cornell University, founded in 1865 as a land-grant institution.

Ohio

An 1825, state law required Ohio counties to fund public education.

Public institutions of higher learning included Cincinnati College and the Medical College of Ohio (1819), the former half of which is now the University of Cincinnati; the Cincinnati Conservatory of Music (1867), established as part of a girls' finishing school and now also part of the University of Cincinnati; The Ohio State University (1870), a land-grant institution; and the University of Toledo (1872).

Private colleges operating soon after the war ended included Buchtel College (1870), a Universalist institution that is now the public University of Akron.

Libraries of significance in the state include the Cincinnati Public Library, which opened in 1853 and evolved from a subscription library established a half-century earlier, and the Columbus Metropolitan Library, which opened in 1873.

Oregon

Educational institutions in the state established soon after the conclusion of the Civil War included Lewis and Clark College (1867), a private institution founded in Albany (and eventually relocated to Portland); Oregon State University, a land-grant institution founded in 1868; and the University of Oregon, founded in 1876.

Pennsylvania

Public primary and secondary education had existed in Pennsylvania since 1790, developing slowly but being well-established by the time of the Civil War. At this time, there were also more than a dozen institutions of higher education throughout the state, including the private University of Pennsylvania (1740); the public University of Pittsburgh (1787); and Pennsylvania State University (1855), which was founded initially as a state land-grant institution even before the passage of the Morrill Act of 1862.

Weeping Willow Schoolhouse, Chester County, Pennsylvania, circa 1860.

Rhode Island

Public higher education in Rhode Island began with the founding of the Henry Barnard School of Law in 1845. Other public institutions included Rhode Island Normal School (1854), now known as Rhode Island College.

Private institutions operating during or soon after the Civil War included Brown University (1764), Bryant College (1863), and Rhode Island School of Design (1877).

Another institution of note, although not established until nearly two decades after the conclusion of the war, in 1884, is the Naval War College in Newport.

Vermont

In 1777, Vermont became the first state to constitutionally mandate funding for universal public education. The state enjoyed a level of prosperity high enough to back up this lofty ideal. By 1850, academies and grammar schools had been established throughout the state and some were providing to both boys and girls a level of education comparable to that available at contemporary colleges. While many of these schools were private institutions and remained so, most nonetheless received funding from municipal governments to educate local students and a number eventually became public schools.

Several of Vermont's grammar schools eventually became colleges, including Addison County Grammar School, which became Middlebury College in 1800; Lamoille County Grammar School, which became Johnson State College in 1828; Orange County Grammar School, which became Vermont Technical College in 1866; and Rutland County Grammar School (1787), which became Castleton State College in 1867. A number of grammar schools were also converted into normal schools in order to meet a growing need for qualified teachers.

Other higher educational institutions operating at the time of the war included the University of Vermont at Burlington, founded in 1791.

West Virginia

When it was founded in 1863, West Virginia did not have as many educational institutions as Virginia, the state from which it had seceded, and those that it had were generally not as large or old. Many of those still in existence now were founded in the years immediately following the war.

Private institutions of higher education operational during the era of the Civil War or founded soon after included Marshall Academy, a private secondary school that evolved into Marshall University; Bethany College (1840); and Broaddus College, a Baptist college established in Winchester in 1871 and named for a minister prominent during the conflict;

Public institutions included West Liberty State College (1837); West Virginia Normal School (1865), now known as Fairmont State University; the Agricultural College of West Virginia (1867), a land-grant institution that is now West Virginia University; Shepherd University (1871); Concord University (1872); and Glenville State College (1872).

Wisconsin

Wisconsin's 1848 state constitution provided for free public education and, in the years following the Civil War, the state was one of the leaders in the establishment of higher-education institutions in the Midwest.

Public institutions that had been founded by or during the era of the war included the University of Wisconsin (1848), which became a land-grant institution in 1866; Platteville Normal School (1866), the state's first institution for training teachers and now the University of Wisconsin — Platteville; and Oshkosh State Normal School (1871), the first normal school in the United States with a kindergarten, and now the University of Wisconsin — Oshkosh.

Private colleges included Carroll College (1846), now known as Carroll University, which was forced by the war and financial problems to suspend its operations during the 1860s; Beloit College (1846), founded by the Friends for Education, a group of four settlers from New England; and Ripon College (1851).

Education in the South

Although public primary and secondary education had been established to some extent in the South — and while some of the country's oldest colleges were in the South, notably Virginia — such institutions were much less widespread than in the North. Plantation owners and other members of the upper class typically either sent their children to private schools or hired tutors to teach them.

In consequence, levels of education and literacy were considerably lower throughout the South than in the North. This is even more profound if the one-third of Southerners who were uneducated slaves is taken into consideration; while some Southern blacks did manage to become literate or achieve some level of education, the Confederate states had laws prohibiting schooling for blacks.

During the period of Reconstruction, the biracial governments of the defeated Southern states established public school systems designed to serve the needs of all children, but these were universally segregated. After the pendulum swung back toward white-controlled government in the years following Reconstruction, black schools tended to be sorely underfunded (although, in general, the postwar South had not distinguished itself as a bastion of education for any of its citizens).

Alabama

Public institutions of higher education in Alabama included Auburn University (1856), which closed during the Civil War when most of its faculty and students joined the Confederate military forces; the Lincoln Normal School (1856), which in 1874 was reclassified as Alabama State University, the nation's first state-supported university for blacks; and Alabama Agricultural and Mechanical University (1875), a historically black land-grant university located in Normal.

Private institutions of higher education included Spring Hill College (1830), a Jesuit school in Mobile; and Talladega College (1867), the state's oldest historically black college, founded by two former slaves with the assistance of the Freedmen's Bureau.

Arkansas

Arkansas' first school was the Dwight Mission, founded in 1822 for Cherokee Indians. In 1843, Arkansas established a statewide system of public schools, but private academies dominated education until a decade after the end of the Civil War.

Arkansas did not have many institutions of higher education prior to the Civil War. Public institutions of this sort founded soon after the war ended included Arkansas Industrial University (1871) in Fayetteville, a land-grant school that is now the University of Arkansas.

Private institutions founded soon after the war included Arkansas College (1872) in Batesville, a Presbyterian school now known as Lyon College; Central Institute (1876) in Altus, founded by the Methodist Episcopal Church and now known as Hendrix College; and Walden Seminary (1877), founded to educate freed blacks west of the Mississippi and now known as Philander Smith College.

Florida

In 1868, Florida adopted a new constitution that authorized voting rights for blacks and a statewide system of public primary and secondary education, upon which the state was readmitted to the Union. The Florida Department of Education was established in 1870.

Public institutions of higher learning included West Florida Seminary (1851) in Tallahassee, now Florida State University, which was reclassified as the Florida Military and Collegiate Institute during the Civil War and whose cadets fought during the conflict; and East Florida Seminary (1853) in Ocala, now the University of Florida.

Private institutions of higher learning included Brown Theological Institute (1866), a historically black school founded by the African Methodist Episcopal Church and now known as Edward Waters College.

Georgia

Despite a promising start during the Colonial era, only limited primary and secondary educational opportunities existed in Georgia throughout the nineteenth century. During Reconstruction, the state legislature mandated a free public school system and, by 1872, a system of segregated schools was available, although often only for three or four months at a time.

Public institutions of higher learning included the University of Georgia (1785) in Athens, which was closed during the last two years of the Civil War.

Private institutions of higher learning included the coeducational Jefferson County Academy (1818), which eventually became the Martin Institute — the first privately-endowed educational institute in the country — and operated under that name until it closed in 1942.

Louisiana

Louisiana's first school is thought to have been the Ursuline Convent for girls in New Orleans, founded in 1727. There was little in the way of public education until 1841, when New Orleans established free public schools and supported them with poll taxes and property taxes.

Public institutions of higher learning in Louisiana during the era of the Civil War included the Louisiana State University Agricultural and Mechanical College (1860), which was founded with land grants from the U.S. government. Its first superintendent was William Tecumseh Sherman, who resigned this position and left to serve in the U.S. Army when Louisiana seceded from the Union in 1861. The school was closed during most of the ensuing war.

Private institutions of higher learning during the era of the Civil War included the Medical College of Louisiana (1834), known today as Tulane University, which was closed from 1861 to 1865 because of the conflict.

Mississippi

Primary and secondary education in antebellum Mississippi was provided by a limited number of private academies, nine of which had been established by 1817. Educational opportunities for blacks did not exist at all until 1862, when a school was established in an area occupied by Union military forces. In 1870, during Reconstruction, the mixed-race legislation of the state attempted to establish public education but resistance to taxation and a relatively poor economy retarded these efforts.

Public institutions of higher learning established prior to or soon after the war included the University of Mississippi (1848) in Oxford, whose School of Medicine was used as a hospital for both Confederate and Union troops during the war; Alcorn State University (1871), a historically black land-grant college founded on the site of the former Oakland College (see below); and Natchez Seminary (1877), now known as Jackson State University, also a historically black school founded to educate freed slaves and their offspring.

Private institutions included Oakland College (1830), a school started by Presbyterians that closed during the war because so many of its students joined the Confederate military forces; Rust College (1866), a historically black school founded by Northern missionaries from the Freedman's Aid Society of the Methodist Episcopal Church; and Blue Mountain Female Institute (1871), now Blue Mountain College, founded by Confederate Brig. Gen. Mark P. Lowrey.

North Carolina

North Carolina's first public primary and secondary schools began in 1840 but were, of course, open only to whites.

Institutions of higher learning included the University of North Carolina (1789) in Chapel Hill, the oldest public university in the country. Many of its students were given exemptions from the Confederate draft and it was one of the few colleges in the South to remain open during the war.

Private institutions of higher education included Trinity College (1838), originally known as Brown's Schoolhouse and now as Duke University; and Wake Forest College (1834), originally as Wake Forest Manual Labor Institute and now Wake Forest University, which closed during the war because most of its students and some of its faculty enlisted in the Confederate military forces.

South Carolina

Prior to the Civil War, private academies provided primary and secondary education in South Carolina. In 1868, a new state constitution called for public education for all children, but this did not actually occur in South Carolina until the 1890s.

Public institutions of higher learning established by or during the era of the war included the College of Charleston (1770), whose founders included three signers of the Declaration of Independence; South Carolina College (1801), now the University of South Carolina, whose students led the movement in the state to secede from the United States; and South Carolina Military Academy (1842), now known as the Citadel, a military college founded on the site of an arsenal in Charleston that claims two of its students participated in the first military action of the war, an attack on a steamer attempting to resupply Fort Sumter.

Private institutions included Wofford College (1854) in Spartanburg and Furman University (1826) in Greenville.

Tennessee

Education in Tennessee was provided largely by private schools and churches until well after the Civil War. Tennessee established a statewide public school system funded by taxes in 1873, during the era of Reconstruction, but it remained underfunded and largely ineffective until the early twentieth century.

Public institutions of higher education included East Tennessee University (1794), originally Blount College and now the University of Tennessee — Knoxville, which was perceived to be a bastion of Union sympathies during the war and which was used as a barracks and hospital and severely damaged during the conflict.

Private institutions included Bethel College (1842), originally Bethel Seminary and now Bethel University, a Presbyterian school in McKenzie; Christian Brothers University (1871), founded by a Roman Catholic religious order and the oldest college in the city of Memphis; and Cumberland University (1842), a Presbyterian institution in Lebanon that, by the 1850s, included schools of law and theology.

Texas

Significant moves toward public education began in 1839 when what was then the Republic of Texas set aside land for two state universities and designated land in each county for public use as primary and secondary schools. Tentative plans for public higher education date to twelve years before this, and are mentioned in the constitution for the Mexican state of Coahuila y Tejas, which the area was known as before the Texas Revolution.

Public institutions of higher education included the Agricultural and Mechanical College of Texas (1871) in College Station, a land-grant institution that is now better known as Texas A&M University. None others were established until the 1880s.

Private institutions of higher education included Baylor University (1845), established by Baptists in Independence (and subsequently moved to Waco and merged with Waco University); Baylor Female Institute (1851), a separate off shoot of Baylor University that merged with it in 1887; and St. Edward's Academy (1878), a Roman Catholic school in Austin that is now named St. Edward's University.

Virginia

Virginia had a long tradition of educational institutions, the Syms Free School being founded in 1634 and the College of William and Mary in 1693. However, the state made no provisions for public education until 1810, when the Literary Fund was established to assist poor children. The state constitution first provided for public primary and secondary schools for all in 1869.

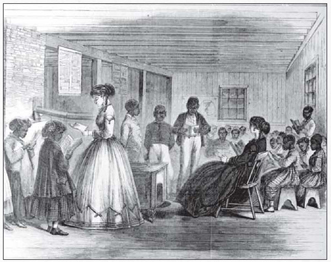

After the war, Northern reformers often came to the South to set up Freedman schools to educate freed slaves, both adult and children.

Public institutions of higher education included the University of Virginia, founded by Thomas Jefferson in Charlottesville in 1819; the Medical College of Virginia (1854) in Richmond; and Virginia Military Institute (1839) in Lexington, whose pre-war faculty included Thomas “Stonewall” Jackson and whose cadets distinguished themselves at the Battle of New Market in 1864.

Private institutions included Washington College (1749) in Lexington, which Robert E. Lee served as president from when the war ended in 1865 until his death in 1870 (the school is now Washington and Lee University); Hampden-Sydney College (1775), a men's-only school that is the oldest private college in the state; and Roanoke College (1842), the second-oldest Lutheran college in the country.

Education in U.S. Territories

In 1785, the Federal government passed a Land Ordinance that set aside a piece of every township in the unincorporated territories of the country for use by public schools and this helped to ensure the availability of education as the country expanded westward. Educational opportunities were, nonetheless, severely limited in the U.S. territories during and in the years following the Civil War. There were, however, a few exceptions to this.

The Arizona Territory, for example, opened its first public school in 1871, and, in 1879, the territory's legislature founded the office of the state superintendent of public instruction.

In the Utah Territory and the State of Deseret, public education began in 1850, when Mormon settlers founded the University of Deseret, the first public university west of the Mississippi River.

And primary and secondary education existed in the Washington Territory (1853–1889) since its earliest days.

Terms

BLUE-BACKED SPELLER: A colloquial name for Noah Webster's guide to reading, spelling, and pronunciation, initially published in 1783 and widely used in primary education during the era of the Civil War and in the decades following it. It was the first part of his three-part A Grammatical Institute of the English Language, which also included a grammar (1784) and a reader (1785).

COMMON SCHOOL: A term coined by educational reformer Horace Mann and used to refer to schools designed to educate people of all social levels and religions. Such schools typically taught reading, writing, arithmetic, history, and geography, and also sometimes geometry, algebra, Greek, and Latin.

FREEDMEN'S BUREAU (BUREAU OF REFUGEES, FREEDMEN, AND ABANDONED LANDS): A Federal government agency that assisted freed slaves from 1865–1872, generally with emergency food, medical care, and housing. It was very unpopular with Southern whites during the era of Reconstruction.

LAND-GRANT INSTITUTIONS (LAND-GRANT COLLEGES, LAND-GRANT UNIVERSITIES): State colleges and universities founded or expanded with the help of Federal land grants (under the provisions of the 1862 Morrill Land Grant Act), in exchange for establishing programs in agricultural, scientific, industrial, and military studies.

MCGUFFEY READERS: A series of progressively more challenging educational texts developed by educator William Holmes McGuffey and his brother in the 1830s and 1840s to teach reading. They were widely used during the Civil War and throughout the century following it.

NORMAL SCHOOL: Taken from the French term école normale, this was a type of school established to train high school graduates to be elementary school teachers. The first private institution of this sort in the United States was founded in 1823 and the first public one was founded in 1839.

SEMINARY: Traditionally, a sectarian school founded for training priests or ministers. During the 19th century in America, however, this term was also sometime applied to institutions, like normal schools, established for providing post-secondary education to teachers.

WHIG PARTY: An American political party that operated from 1833 until 1856 and was formed in opposition to the policies of President Andrew Jackson. Among other things, the party supported economic protectionism, modernization, and the supremacy of Congress over the presidency. It was destroyed by internal dissension over the question of whether or not to permit the expansion of slavery into U.S. territories.