5

RELIGION: WHAT PEOPLE BELIEVED

“… Congress should not establish a religion, and enforce the legal observation of it by law, nor compel men to worship God in any manner contrary to their conscience …” — James Madison, 1789

When the Civil War erupted at the start of the 1860s, America already had a well-established and diverse religious tradition that had developed over the previous two centuries and was an amalgamation of Old World and indigenous institutions. From the seventeenth century onward, successive waves of immigrants had brought their religious traditions to the shores of the New World and, over the years, these had evolved in their new home and been joined by new ideas, customs, and beliefs.

Freedom of religion was a fundamental tenet in America and, while the young nation's citizens were not always as sympathetic with or tolerant of the ideologies of others as they might have been, they nonetheless availed themselves of the liberty to practice their own beliefs.

Overall, Americans of the era had an ambivalent attitude toward religion; the overwhelming devotion of some was off set by the indifference of others. A great religious movement called the Third Great Awakening did commence in the years just prior to the Civil War. In that it was targeted at the unchurched, however, the movement may very well not have occurred if a need for widespread conversions and the improvement of society had not been perceived among the most fervent of the faithful.

President Abraham Lincoln himself exemplified this split mindset to a great extent. On the one hand, he was the first U.S. president to use the phrase “This nation under God,” which, along with his thorough knowledge of the Bible and frequent reference to an almighty God, inspired his successors and is often taken as evidence of his piety. On the other hand, Lincoln was never baptized and was the only U.S. president to never join a church.

American religious life had its basis in the religions of the nation's earliest settlers, particularly the English, Scots, and Germans.

Another dichotomy existed among some of the most religious of the generals on either side who, while not averse to warfare in general, curtailed their pursuit of it to some extent on Sundays. Union Maj. Gen. William Rosecrans, for example, declined to pursue a retreating Rebel force on the Sabbath. Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson would only engage in “more ordinary battles” on Sundays, and others chalked up their defeats to the fact that they had fought on the day of rest.

In any event, religious leaders in both the North and the South generally took the stance that the side of which they were part represented “right and truth and justice” and that their enemies were engaged in “wrong and malice and outrage,” in the words of one contemporary clergyman.

Religious Denominations

Initially, American religious life had its basis in the religions of the nation's earliest settlers, particularly the English, Scots, and Germans, who brought with them a variety of Protestant denominations and Catholicism. To these were added the religious beliefs of Irish, Scandinavians, southern and eastern Europeans, and others, who brought their own traditions, including various strains of Orthodoxy and Judaism. New denominations were established in America as well, and many of these went on to become mainstream religions in their own right.

Early in the history of the republic, various states had established churches that they supported with tax revenues, following a tradition that had been observed since the Colonial era. This was, however, deemed to violate the doctrine of separation of church and state called for by the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, and by 1833 all the states had discontinued this practice. (“Separation of church and state” does not actually appear in the Constitution itself and can instead be traced to an 1802 letter by Thomas Jefferson on the subject.)

Churches' structures throughout America differed greatly at the time of the Civil War, from small, austere structures in rural areas to much larger, more elaborate places of worship in the major cities of both North and South. Houses of worship also varied according to the tenets of the faiths practiced in them, the ethnicity of their primary worshippers, and the affluence of the religions to which they were dedicated.

Sects and denominations active in the United States beyond those described in detail in this chapter include the Congregationalist, Disciples of Christ/Christians, Dutch Reformed, Friends, German Reformed, Mennonite, Moravian, Shaker, Spiritualist, Swedenborgian, Unionist, Unitarian, and Universalist churches.

Overall, according to 1860 U.S. Census data, there were well over fifty-thousand churches of various denominations and sizes established throughout the United States at the time of the Civil War — about 60 percent of them in the North and the balance in the South — with estimated total property valued at $169,074,197. The number of churches and the value of property associated with individual denominations is provided in the listings that follow as an indicator of their relative size and influence.

About 25 percent of the combined population of the South, white and black, were members of various churches, and an estimated 64 percent of Southerners are believed to have attended religious services regularly.

Methodists

Methodism was the largest and most widespread religion in the United States at the time of the Civil War. Methodism expanded throughout the country, especially, the frontier, during the Second Great Awakening, when ministers called circuit riders traveled from community to community, spreading the word, establishing relationships with families, and converting the unchurched. There were nearly twenty thousand Methodist churches in the United States at the outbreak of the war, somewhat more than half of them in the North. Total value of Methodist church property in the country at that time was $32,888,421.

Although Northern and Southern Methodists had separated in 1845, bishops in the Confederate states were initially wary of secession.

Presbyterians

In 1860, Presbyterians were one of the major denominations in the United States and, beyond their main branch, could be further divided into three major sects, Cumberland Presbyterians, Reformed Presbyterians, and United Presbyterians. Many of these divisions had occurred or been reinforced during the First and Second Great Awakenings.

At the time of the Civil War, there were some 5,048 Presbyterian churches in the country, about two-thirds of them in Northern states, along with 820 Cumberland Presbyterian churches (more than 80 percent in the South), 136 Reformed Presbyterian churches (125 of them in the North), and 389 United Presbyterian churches (all but a couple of them in the North). Overall value of Presbyterian church property in 1860 was an estimated at $24,028,859 ($914,256 Cumberland Presbyterian, $386,635 Reformed Presbyterian, $1,312,275 United Presbyterian).

Presbyterian leaders in the South initially sought to prevent involving the church in secession or the politics associated with the war. In October 1861, however, the Southern members of the Presbyterian General Assembly met to establish the Presbyterian Church in the Confederate States.

Episcopalians

Essentially an Americanized form of Anglicanism, the Episcopal Church was formed in the wake of the American Revolution in order that a religion in communion with the Church of England might exist but not compel Americans to pledge loyalty to the English monarch. The root religion had, in any event, been well-established in America since the Colonial era, where it had been the official religion in Virginia since its earliest days and spread outward from there.

Episcopalian ministers in the South generally opposed support of secession and instead prayed for the preservation of the nation as a whole. There were notable exceptions to this, of course, as in the case of Bishop Leonidas Polk of Louisiana, who went on to become a Confederate lieutenant general. By the fall of 1861, Episcopalian clergy in seven Southern states had formed the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Confederate States and approved a new constitution for it (members from North Carolina, Tennessee, Texas, and Virginia abstained from these actions).

There were more than 2,100 Episcopalian churches established throughout America at the onset of the Civil War, about two-thirds of them in the North and one-third of them in the South. Value of Episcopal church property at that time was $21,481,498.

Baptists

On the eve of the Civil War, Baptists were one of the largest denominations in the country and among those that were considerably more widespread and influential in the South than in the North. At the time of the Civil War, there were some 11,219 Baptist churches in the country, with about two-thirds of them in Southern states (this is an especially telling proportion when one considers that the white population of the North was about three-and-a-half times larger than that of the South). Value of Baptist church property was an estimated $19,746,378.

In 1845, Northern and Southern Baptists split over the issue of slavery, and the latter formed a separate denomination under the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC); the leaders of this off shoot denomination strongly supported secession and were in favor of the South becoming its own nation. Then, in the years following the war, many blacks split off from the SBC and established their own congregations.

A number of smaller Baptist sects also existed throughout the country at the time of the war, and these sects included the Free Will Baptist (530 churches, property value $789,295), Seventh Day Baptist (fifty-three churches, property value $107,200), Six Principle Baptist (nine churches, property value $8,150), and Winnebrenner Baptist (sixty-five churches, property value $74,175). Approximately nine out of ten Winnebrenner Baptist sects were located in Northern states.

Lutherans

German and Scandinavian immigrants brought Lutheranism with them to America, with significant numbers of them arriving in the 1830s and 1840s. At the time of the Civil War, there were some 2,125 Lutheran churches in the country, about six out of seven of them in Northern states, especially Indiana, Ohio, Michigan, and Missouri (although a significant number of those in Southern states were located in south Texas, were large numbers of German immigrants settled from about 1848 onward). Value of Lutheran church property was an estimated $5,352,679.

Roman Catholics

America was predominantly a Protestant country on the eve of the Civil War, which contributed to significant anti-Roman Catholic sentiment and the marginalization of Catholics. There were nonetheless a number of significant Catholic redoubts throughout the country, some of the most notable being Baltimore and southern Maryland, the latter of which had been settled by Jesuits starting in 1634. Large numbers of Irish immigrants that began to arrive in the United States beginning in the middle of the nineteenth century swelled the number of Catholics in the country and helped to bolster the strength of the religion.

By 1860, there were 2,117 Catholic churches active in Northern states and 539 in Southern ones. Roman Catholic property in America at the time of the Civil War was valued at $26,047,159.

African Methodist Episcopal Church

The Second Great Awakening was the defining event in the spread of Christianity among blacks in the United States when, during the revivals associated with it, Baptist and Methodist ministers converted large numbers of them. As slaves or, at best, second-class citizens, many blacks were disappointed with the way they were treated by whites with the same religious beliefs and at the lapsed promises from many of them to support abolition. As a result, from the late eighteenth century onward, the strongest black religious leaders began to form their own denominations, and a number of independent black Baptist congregations were among the most significant of these. Minister Richard Allen and his colleagues separated themselves from the Methodist Church and founded what would become one of the largest and most successful, the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, in Philadelphia in 1815. This new denomination thrived and, by 1846, it had expanded to 296 churches with 176 clergymen clergymen and 17,375 members.

America was predominantly a Protestant country on the eve of the Civil War, which contributed to significant anti-Roman Catholic sentiment and the marginalization of Catholics.

Church of the Brethren

Colloquially known as Dunkers (as in the “Dunker Church” on the Antietam Battlefield), the Brethren were a type of Baptist that was established primarily in the Northern states. At the onset of the Civil War, there were some 163 Church of the Brethren churches in the United States with a total property valued at $162,956. Like other religious groups that opposed the war on moral grounds, the Brethren were persecuted for being pacifists. While its members were ultimately exempted from military service upon payment of a $500 fee, some still paid heavy prices for their position. One Brethren leader, for example, became distrusted by the authorities for providing medical assistance to the wounded of both sides, and as a result was jailed without legal reason and, in the summer of 1864, attacked and killed.

Adventists

Adventism started as an interdenominational movement during the Second Great Awakening and was based on a belief in the imminent second coming of Jesus Christ. At the start of the Civil War, there were some seventy Adventist churches in the country, all of them located in Northern states. Total value of Adventist church property was $101,170.

Quakers

Members of the Society of Friends, better known as Quakers, were well established in America by the time of the Civil War and, in 1860, they had 663 churches established in Northern states — particularly Pennsylvania, which was home to nearly a quarter of them — and sixty-two churches in Southern states. Total value of church property was valued at $2,534,507.

As pacifists unwilling to serve in the military forces of either the Union or the Confederacy during the war, Quakers were treated with suspicion by the governments of both sides.

Jews

The first Jews, some twenty-three of them, arrived in what was to become New York City in 1654. Judaism thrived in the New World — although it did not expand as quickly or to extent that other denominations did in the early years of America — and was bolstered by the arrival of highly-educated German Jews who began to arrive in the mid-nineteenth century and establish themselves as merchants in cities and towns across the country. By 1860, there were some fifty-two synagogues established in Northern states and nineteen established in Southern ones (notably Charleston, South Carolina). Total value of Jewish ecclesiastic property was valued at $1,125,300.

Jewish troops served in both Confederate and Union regiments during the war. Prominent Jews included Judah P. Benjamin, the first Jewish U.S. senator and a member of Confederate President Jefferson Davis' cabinet.

Mormons

More properly known as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Mormonism was founded in western upstate New York by Joseph Smith Jr. in 1830 after he claimed to experience a series of visions, visitations from angels, and revelations from God. Mormon beliefs were atypical to say the least — and included a new written canon and practices like polygamy — and adherents of the new faith were savagely persecuted as a result and driven further and further westward. Smith himself was murdered in 1844 and his successor, Brigham Young, led the members of the church to the unregulated Utah Territory.

There were just two Mormon churches in the country in 1860, both of them in Northern states. The total estimated value of their property was $1,100.

The Great Awakenings

Three “Great Awakenings,” widespread evangelical movements that transformed the religious landscape of America, took place in the 130 years or so leading up to the outbreak of the Civil War. Each of these events had significant and permanent effects on the institution of religion in the country and was based on forceful evangelism and large-scale events, such as revivals and camp meetings. They encouraged people to be passionately involved in their religion and, in addition to attending church, to also study the Bible at home on their own. Each followed, to a great extent, on the momentum of the one preceding it.

The First Great Awakening took place in the 1730s and 1740s, during the Colonial era, and was a wave of religious fervor that moved away from ceremony and ritual, challenged established authority and changed the way people worshipped. This event instilled churchgoing Protestants with a profound sense both of personal guilt and salvation through Christ; caused division among various denominations, notably the Congregational and Presbyterian churches; and was used by Baptist and Methodist ministers to bring Christianity to enslaved blacks in the South. It helped to consolidate the Presbyterian, Baptist, and Methodist denominations as the largest in the country by the early part of the nineteenth century. The Anglican, Quaker, and Congregationalist churches generally opposed the movement and were both divided by and left out of it.

The Second Great Awakening took place during the first three decades of the 1800s and focused largely on non-churchgoers and the idea that all people could be saved through revivals. It resulted in millions of unchurched people joining established churches and in the foundation of many of the new denominations that appeared in America during the nineteenth century. During this time, evangelism and camp meetings became hallmarks of American religious life. It also encouraged the creation of reform movements and benevolent societies designed to heal the ills of society ahead of the second coming of Jesus Christ. As with the movement that preceded it, Methodism in particular prospered during the Second Great Awakening and became the country's biggest and most widespread religious denomination. Presbyterians and Baptists, too, were very active in the movement — and the latter denomination in particular benefitted from it — but distanced themselves from the most fervent elements once they began to lose control of their roles in them.

The Third Great Awakening began in the late 1850s and continued on through the era of the Civil War and up to the end of the century. Its hallmark was a strong sense of social activism and, as with the previous movements, it affected primarily the pietistic Protestant denominations (that is, those that emphasized a vigorous Christian lifestyle and individual piety). It, too, drew strength from the idea of a second coming of Christ that would be precipitated by a general reformation of the world, and many of its adherents set about trying to eradicate social problems like alcohol abuse, bad hygiene, child labor, crime, inadequate education, inequality, pornography, prostitution, racism, slums, weak labor unions, and war. Its followers were, to a great extent in the North, at least, supporters of the Republican Party (the party of Lincoln) which, in that era, was characterized by social progressiveness.

While the Second Great Awakening occurred to a great extent on the frontier, the third was centered primarily in towns and cities. Various denominations sought to accomplish their goals through vigorous outreach to the unfaithful, worldwide missionary work, and establishment of colleges and universities. Revivals were also a major component of the movement, and some areas experienced so many of them that they acquired appellations like “the burned-over district.” An estimated one million people in America — one in thirty, including blacks — converted during this movement and a like number are believed to have been reinvigorated in their faith.

In the North, the Third Great Awakening was, to a great extent, interrupted by the Civil War and lost momentum among the civilian populace until after the war's conclusion. In the South, however, it continued largely unabated, primarily within the Baptist church, which benefitted from it greatly. In any event, many clergymen on both sides, but especially in the North, believed that the war heralded the second coming of Christ.

The Third Great Awakening also extended into the camps of the opposing armies and, over the course of the war, huge revivals broke out within them and as many as 10 percent of Civil War soldiers may have been converted to Christianity during the war (an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 in the Northern forces and an estimated 150,000 in the Southern forces).

Benevolent Societies

Benevolent societies were a type of institution established throughout the United States in the early nineteenth century and several were active at the time of the Civil War. Such groups were a direct outgrowth of the evangelical movement as exemplified in the Second and Third Great Awakenings. They included the American Bible Society (1816), the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions (1812), the American Baptist Home Missionary Society (1832), the American Sunday-School Union (1817), and the American Tract Society (1825).

Such groups were devoted to the salvation of souls through the extirpation of social ills and were used by the evangelical movement to Christianize America. Many of them were active in the military camps of both sides, where they sought to save the souls of soldiers and gain converts to Christianity from among the unchurched.

“The evidence of God's grace was a person's benevolence toward others,” wrote Presbyterian evangelist Charles Grandison Finney, a major figure in the Second Great Awakening.

One of the means benevolent societies used for spreading their various messages was through tracts, and tens of millions of these were distributed throughout the course of the war (for example, the U.S. Christian Commission by itself distributed some thirty million tracts).

For many women volunteers, involvement with benevolent societies or the activities of groups like the U.S. Sanitary Commission was their first experience with work outside the home.

Chaplains

At least 3,694 clergymen are known to have served the opposing sides as military regimental or hospital chaplains, nearly two-thirds of them for Northern forces and the balance for Southern units. They came from every major religious denomination in the country, and the best of them shared the hardships with the men to whom they ministered and made a difference in their lives.

While there were many overtly pious men on both sides — including generals like Union William S. Rosecrans and Confederate Robert E. Lee, Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, and Leonidas Polk, who was an Episcopal bishop — many commanders nonetheless viewed chaplains as extraneous, obstructive, or even a bit suspect. Such uniformed ministers ran the gamut from those with true ability, dedication, and a sense of ministry on the one hand, to those who were out of their depth, looking for an easy job, or seeking personal gain on the other.

The role of chaplains and their place in the unit chain of command was only poorly defined during the Civil War and those in the Army did not have any organization above the regimental level (this situation was, in fact, not significantly changed until after the conclusion World War I, in 1920). Their primary mission was, in any event, the spiritual well-being of the soldiers in their regiments (or ships for those in the opposing navies). And the best of those who served used the flexibility afforded them to make the most of their positions in their units.

Attitudes of troops toward chaplains varied widely, from those who welcomed uniformed ministers to those who, in the words of one Catholic chaplain, “could find their way to hell without the assistance of clergy.”

Actual duties of chaplains varied widely and were an amalgam of those they undertook of their own initiative and those directed by their commanders. These duties included any and all of the responsibilities associated with conducting Sunday services, offering prayers at daily formations, serving as a friend to lonely and isolated troops, distributing tracts, tending to the sick, and retrieving wounded soldiers from the battlefield.

Union Chaplains

Some 2,398 clergy members served as Union hospital, navy, or regimental chaplains (2,154 in the latter capacity). They ranged in age from 19 to 76 years of age, the average chaplain being somewhat more than thirty-eight. Their terms of service ranged from less than a month to being thirteen-and-a-half months.

The average Union chaplain was a bit older than thirty-eight.

Denominations they represented included Methodist (38 percent), Presbyterian (17 percent), Baptist (12 percent), Episcopal (10 percent), Congregational (9 percent), Unitarian/Universalist (4 percent), Roman Catholic (3 percent), and Lutheran (2 percent), with other denominations collectively representing 5 percent.

Early in the war, chaplaincy in the Union forces was open only to ordained Christian ministers; Jewish rabbis were prevented from serving in this capacity, which led to significant outcry and was reversed by the summer of 1862. And, just as they were not allowed to serve as Union soldiers until 1863, blacks were not allowed to serve as chaplains until then, after which as many as seventeen were commissioned as uniformed clergymen. In at least one case, however, the paymaster general paid black clergymen as laborers, rather than the commissioned officers that they were, and at a rate of only $10 a month. At least one woman also sought to become a regimental chaplain but, despite the blessing of Abraham Lincoln himself, was denied by the War Department; serving at her own expense, she was not officially recognized until after the end of war, not given any pay until eleven years after the conflict ended, and was denied disability benefits.

Initially, pay for Union military chaplains was $145.50 per month, with three daily rations and forage for one horse. On July 17, 1862, however, the War Department reduced compensation for chaplains to just $100 per month, two daily rations, and forage for one horse. Furthermore, the paymaster general of the Union armed forces interpreted the regulations to mean that chaplains should only receive pay while on active duty, and, unlike other soldiers, they were thus deprived of remuneration while on leave. This situation had to be rectified by an act of Congress, which was passed April 9, 1864, a full three years into the war.

Standards for Union chaplains were also tightened in July 1862 (for example, they were required to produce letters of reference from five other clergymen of the same denomination). The War Department ordered that chaplains already assigned to units to be retroactively held to such standards, but regimental commanders had a great deal of leeway with regard to those they wished to retain.

Very early in the war there was little specifying what chaplains should wear, and many commanders dictated that they should be attired in civilian garb appropriate to their role as clergymen. In November 1861, the war department dictated that the official uniform for chaplains should be a plain, black officer's frock coat with a single row of buttons, black trousers, and a black hat. There was much variation from regiment-to-regiment, however, and some chaplains even found it expedient to wear a regular captain's uniform, commensurate with their pay grade, in order to emphasize their position as commissioned officers, and many who did so also wore swords for the same reason. Many Union chaplains also augmented whatever ensemble they wore with a blue waist sash — inspired, in part, by the green sashes worn by surgeons — and with various other regalia, such as embroidered gold crosses on their epaulets. The regulations dictating the uniforms for chaplains were revised in 1864, but this had little impact on what was actually done in the field.

Throughout the course of the war, some eleven Union chaplains were killed in action, another four were mortally wounded, and seventy-three suffered non-combat deaths. The rigors of military life were evident in the post-war mortality rates of many of them, however, and about two hundred of them died either by 1871 or at inordinately young ages.

Ninety-seven Union chaplains received special commendations for their service, notably caring for the wounded and being incarcerated as prisoners of war. Four were awarded the Medal of Honor, one for leading a counterattack after the leadership of his regiment had been annihilated. Of the roughly two thousand who served the Union, 112 of them did so for three years or longer.

Confederate Chaplains

More than 1,300 Southern clergymen and soldiers accepted commissions as chaplains with Confederate military units between 1861 and 1865. About half of them were thirty years or younger in 1861. Some 14 percent of eligible clergy in the South ultimately served as chaplains during the war.

About half of the Confederate chaplains were under the age of thirty.

Initially, there were no provisions for chaplains in Confederate military units, and Southern leaders focused on organizing and arming their forces without consideration for them. There were a number of reasons for this, and they included the lack of an existing military tradition that included chaplains — only one, who taught at U.S. Army Military Academy at West Point, was on the rolls in the years leading up the war — and a lack of their perceived value from Southern leaders who included C.S. President Jefferson Davis. Almost immediately, however, Southern clergymen hoping to serve as Confederate military chaplains began to protest this disregard and to petition the government to address it.

In late April 1861, the Virginia Convention for Secession directed the governor to appoint one chaplain for each of the state's brigades. Then, less than a week later, on May 2, the C.S. Congress passed a bill authorizing the president to commission chaplains and assign them to various units as appropriate.

Confederate chaplains served at the regimental, brigade, and even corps level, and in a variety of other posts as well, such as at hospitals, but all were considered to hold the same rank and none had command authority.

Pay for Confederate military chaplains was initially set at $85 a month, with no allowances for meals, forage, quarters, uniforms, or the like. Within two weeks, however, the C.S. Congress reduced the pay for chaplains to just $50 a month, an action that sparked outrage amongst the religious throughout the South. Ministers with families simply could not afford to serve in the military for any extended period of time.

Chaplains were eventually provide rations equal to those of privates and lobbying by religious organizations prompted the Confederate government to raise the pay for chaplains to $80 a month by the spring of 1862. In 1864, chaplains were also provided with forage if they owned a horse and an allowance for stationery. Individual commanders also sometimes provided nominal subsistence to chaplains, such as firewood in the winter or an issue of clothing.

No particular training, experience, or other qualifications were required for a chaplain to be commissioned into the Confederate military. Many of those chaplains who were ordained ministers had received their training through apprenticeships to older clergymen in their own churches rather than at seminaries, which were few and far between in the largely rural South. Most of the rest had studied at universities in the South, while a handful had received their educations in the North or Europe.

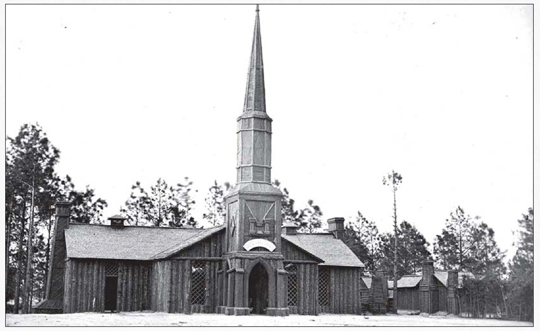

The 50th New York Volunteer Engineer Regiment built this log church in Poplar Grove, Virginia.

Denominations for somewhat more than seven in ten Confederate chaplains are known, and these included Methodist (47 percent), Presbyterian (18 percent), Baptist (16 percent), Episcopal (10 percent), and Roman Catholic (3 percent), with Cumberland Presbyterian, Lutheran, Disciples of Christ, Missionary Baptist, and Congregational each representing less than 1 percent each. The Presbyterian and Missionary Baptist denominations each sent missionaries to the Confederate forces, and the former group also sent commissioners to recruit chaplains from the ranks to fill available openings. Missionaries were often better paid by their churches than they would have been by the military, something that allowed them to stay in the field with the armies. The Southern churches were, in any event, generally slow to provide chaplains early in the war.

Confederate chaplains had no authorized uniforms, rank, or insignia, and many simply wore the same attire they did in their role as civilian clergy. Some also wore uniforms based on those worn by other Confederate officers, especially surgeons, or modified or created their own outfits, insignia, and accessories. As the war dragged on and resources dwindled, however, many simply wore whatever was available, like most of the other personnel in the Southern ranks.

During the war, nine Confederate chaplains were killed in action or as the result of their wounds, thirty-two died from illness or other causes, and twenty were wounded but not killed as result of their injuries.

Terms

ARMINIANISM: A school of thought within Protestantism based on the ideas of Dutch Reformed theologian Jacobus Arminius that provided much of the theological basis for the Second Great Awakening.

BIBLE STUDENTS: A religious movement started in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, in 1870 by minister Charles Taze Russell that was one of the sects inspired by the spiritual fervor of the Third Great Awakening and which eventually became known as Jehovah's Witnesses.

CHAPLAIN MILITANT: A term used for Union chaplains who chose to wear the same uniforms as other officers rather than the regular black garb authorized for military clergymen.

CONFEDERATE MEMORIAL DAYS: Holidays that differed by state and which were observed in the South in lieu of Decoration Day in the North.

DECORATION DAY: The predecessor to Memorial Day, this holiday was first observed on May 5, 1866, in Waterloo, New York, to honor those slain in the Civil War and included parades, placing flowers on graves, and flying flags at half-staff. It was celebrated on a national level for the first time on May 30, 1868, almost three years to the day that the last Confederate army surrendered.

DUNKARD, TÄUFER, TUNKER: Variant names for the Dunker sect, more properly known as the Old German Baptist Brethren, a denomination that practiced adult baptism by immersion and appeared in America starting in 1719, after some of its adherents fled persecution in Germany.

HOLY JOE: A nickname for military chaplains used primarily by U.S. troops.

NEW LIGHTS: A term used for ministers who adopted an evangelical style of preaching during the Great Awakenings. Compare with old lights.

OLD LIGHTS: A term used for ministers who retained a traditional style of preaching during the Great Awakenings. Compare with new lights.

U.S. CHRISTIAN COMMISSION: A civilian agency founded by the Young Men's Christian Association during the war to offer religious support and other services to military personnel. It was very evangelical in nature and competed throughout the war with the “godless” U.S. Sanitary Commission.

U.S. SANITARY COMMISSION: A civilian commission, strongly supported by the Federal government, that looked after the well-being of troops by providing them with food, medicine, and clothing; helped to oversee their living conditions; and established field hospitals for them. The commission had more than four thousand local branches and held fundraisers, such as art exhibitions or teas, which they called Sanitary Fairs. It was strongly influenced by a Universalist leadership and was constantly at odds with the evangelical U.S. Christian Commission.

WOMAN'S CHRISTIAN TEMPERANCE UNION: A non-sectarian women's organization founded in 1874 at a national convention in Cleveland, Ohio, that spearheaded a national crusade for prohibition that various local groups had started in the preceding years. Members fought intemperance by going into saloons where they sang, prayed, and urged bartenders to stop selling alcohol.

YOUNG MEN'S CHRISTIAN ASSOCIATION: Better known as the YMCA, this evangelical group devoted to the idea of “muscular Christianity” was founded in 1844 and active during the Civil War, attempting to take over the operations of the military's chaplain corps in 1861–62. It founded U.S. Christian Commission.