6

FUN AND GAMES: HOW PEOPLE ENTERTAINED THEMSELVES

“No human being is innocent, but there is a class of innocent human actions called Games.” — W. H. Auden

During the nineteenth century, people were less accustomed than modern Americans to constant sensory bombardment. Nonetheless, civilians and soldiers alike enjoyed games, music, spectator and participant sports, and other recreations as diversions from the problems and tedium of everyday life or a mental escape from the specter of combat and death.

Entertainment in the North

Society in the North was becoming increasingly urbanized and diverse, and many forms of entertainment evolved that were both tailored to large crowds and likely to suit a wide variety of tastes and backgrounds. Spectator sports like horse racing and boxing were popular. Gambling was also popular, both on spectator sports and at the gaming table, and people often played casual card or board games with friends and family.

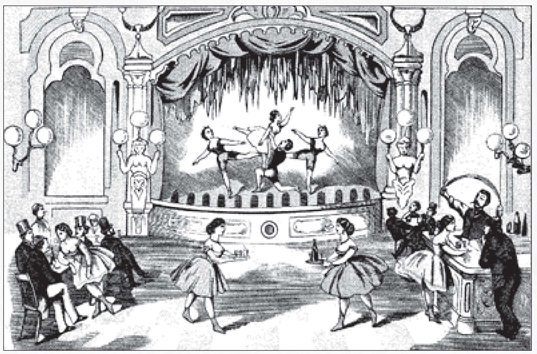

Theater, another largely urban form of entertainment, evolved during the nineteenth century, and vaudeville and burlesque emerged as unique forms of staged entertainment for the masses. Circuses, in both cities and the country, also came into their own as a distinct form of entertainment, especially in the years following the Civil War.

Entertainment in the South

Being less urbanized than the North, people in the South tended toward smaller-scale kinds of entertainment, especially prior to the war. Balls held by the upper crust, activities shared by farm families, and festivals celebrated in towns, villages, or plantations predominated.

Venues for spectator activities, such as baseball parks or race tracks, were much less wide-spread than in the North. Participant sports, however, such as horse racing among the members of a club or village, were likely activities.

Travelling circuses and carnivals, especially in conjunction with county or state fairs, were also popular, and broke up the day-to-day routines of rural life.

Shortages imposed by the war changed the nature of many social activities, of course, but Southerners still enjoyed them. “Biscuit parties” were thrown by those able to obtain some wheat flour or by friends who might each bring what they had available. Later in the war, when for many there was not flour or anything else to be had, people held “starvation parties,” where the only refreshment served was water.

Games

Card, board, and dice games were popular among civilians and soldiers alike. Because of the monotony of camp life, many soldiers in particular spent as much time as they could absorbed in games when other duties did not call.

Dice were generally small, a bit crude, and made out of wood (although some might be made from flattened musket balls, such as those of the Revolutionary War, among troops still using muskets). Craps was the dice game played most often, but others included one known variously as birdcage, chuck-a-luck, or sweet cloth. Skewed results or even cheating were easily facilitated by the fact that so many dice were imperfect, or even designed to produce certain results more often than others.

Later in the war, when for many there was not flour or anything else to be had, people held “starvation parties,” where the only refreshment served was water.

Board games included checkers, chess, and backgammon, more-or-less in that order of popularity. Checkers, in particular, were popular throughout the armies and navies of both sides. Boards used by soldiers in the field might be handmade and were small so as not to be an encumbrance. Checkerboard patterns in red and green or red and yellow were as common as today's more familiar red and black. Chess was played much less frequently, but was not unknown at the time.

Although soldiers enjoyed gambling, many considered gambling to be a mortal sin. As a result, soldiers would play cards or dice right up until marching off to battle, then destroy or discard their gaming implements so they would not be upon their persons if they were slain.

Soldiers — enlisted men and officers alike — played many different card games including draw poker, cribbage, euchre, faro, keno, seven-up, and twenty-one. Regiments tended to have games that they favored, poker being the most common. Such games were usually played for stakes, which, among less-than-friendly groups, could lead to sore feelings or even charges of cheating.

While dice and board-game components were frequently crude or homemade, many sorts of manufactured playing cards were available. During the Civil War, numerous varieties of decks were produced that replaced traditional playing-card symbols with military and patriotic imagery. The Union Playing Card Company, for example, replaced the traditional suits of spades, clubs, hearts, and diamonds with eagles, shields, stars, and flags. Similarly, a deck manufactured in the South depicted a different Confederate general or cabinet member on each card in the deck.

Although soldiers enjoyed gambling, a preponderance of men considered gambling, or “throwing the papers,” to be a mortal sin. As a result, soldiers would play cards or dice right up until marching off to battle, then destroy or discard their gaming implements so they would not be upon their persons if they were slain. After the battle, survivors eager for a game would search the former campsite for their cards or dice or purchase new ones from sutlers, the traveling merchants who followed the armies during the war.

Other games, such as jackstraws, were also played by some civilians and soldiers, and games like prisoner's base were also popular with children.

Music

Soldiers had little of their time occupied by battle, and found many ways to fill the lonely hours of camp life.

Singing as a group activity was a common activity in the nineteenth century, whether hymns by the devout or bawdy drinking songs among comrades, and soldiers in the field often sang around the proverbial campfire (see Appendix E). Lyrics to popular songs tended to be widely-known, especially in the armies, where they were often disseminated rapidly.

Many people also owned and knew how to play a wide variety of instruments, banjos being among the most popular. While the banjo is today associated with Appalachia and the South, it was as likely to be played in the camps of either side. Pianos might be found in middle-class or wealthy homes or saloons, while portable instruments — like harmonicas and mouth harps — were more likely to be found in the hands of the less affluent or those who had to carry their possessions or had less room to store them, such as soldiers or sailors.

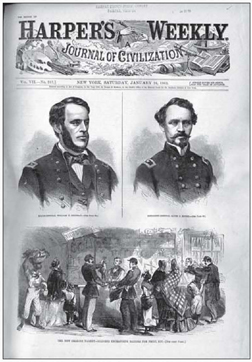

Harper's Weekly and Godey's Lady's Book were popular and common publications during the Civil War.

Reading

Many sorts of reading materials were available to people during the Civil War, among them publications such as Harper's Bazaar and Godey's Lady's Book, classic and popular literature, and a wide variety of daily and weekly newspapers (newspapers are discussed in greater detail under Communications in chapter 10). Many families entertained themselves by listening to one member read aloud from a novel or periodical.

Popular novelists of the day included Louisa May Alcott and Augusta Jane Evans, and, in the years following the war, Mark Twain, whose Innocents Abroad was published in 1869, and former Gen. Lew Wallace, whose Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ, was published in 1880. Popular among many readers were dime novels, which detailed the often exaggerated adventures of people like Buffalo Bill and other heroes of the far West.

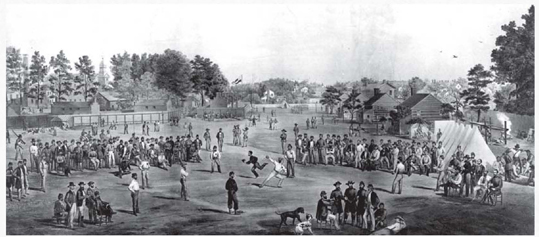

An 1863 illustration of Union prisoners playing baseball at a Confederate prison in Salisbury, North Carolina. This image likely bears very little resemblance to the actual conditions found in a Southern prisoner-of-war camp.

Many sorts of magazines and newspapers were also readily available and covered a wide variety of themes, including agriculture, art, children's literature, education, etiquette, fashion, fiction, finance, gardening, home architecture, humor, labor reform, medicine, music, politics, religion, sports, and women's issues. And, with subscription rates as low as $2 to $4 per year, such publications could easily be obtained by most people interested in them. After the war ended, numbers of such publications increased markedly and, by 1870, almost six thousand different periodicals were being published in the United States.

Sports

Sports, both as participant and spectator events, were popular with people during the mid-nineteenth century. Prior to the Civil War, horse racing and boxing were among the most popular spectator sports with many Americans, especially in the North. Race tracks with open green space were especially popular in crowded urban areas.

After the war, baseball entered the scene as America's most popular pastime, a role it has continued to play to a lesser-or-greater extent. Other popular sports included football, cricket, heel-toe walking races, and horse trotting.

Theater

Prior to and during the nineteenth century, American theater was heavily influenced by trends in Europe. In Europe as well as America, the Industrial Revolution created a need for entertainments geared toward the tastes of working-class people, such as pantomimes, spectacles, melodrama, and the previously-mentioned vaudeville. And, on a somewhat higher plane, there were romantic dramas and revivals of classic operas and plays, including Shakespeare.

Several different sorts of variety shows arose during the nineteenth century as forms of entertainment for the great masses of working people, many of them immigrants living in the rapidly-growing urban areas. Music halls in England and minstrel shows and burlesque in America often employed coarse humor and were generally considered appropriate fare for saloons or male-only audiences. More wholesome variety shows and vaudeville arose in the years following the Civil War as a response to the growing demand for family entertainment.

Because the North was more urbanized, such forms of entertainment were better known there than in the South, but these would have been found in larger cities like New Orleans.

Music Halls

At the time of the Civil War, music halls were the most popular form of mass entertainment in England. These were theaters or taverns with stages where people could drink, hear and sing popular songs, and watch dance routines, comedy, magic, and other acts, all presided over by a master of ceremonies. Many of the professional music hall entertainers became famous throughout England and some of them even toured the United States.

Minstrel Shows

While music halls were largely a phenomenon peculiar to England, minstrel shows were indigenous to the United States. Together, they helped to influence the rise of the burlesque and vaudeville variety shows in America.

Also called blackface shows, minstrel shows had existed in America since Colonial times, mainly as short acts with travelling carnivals. In the 1820s, troupes like the Virginia Minstrels began to put on full-length variety shows and, before long, these spread throughout the United States and to England, where they joined other music hall acts. During the 1840s, the Virginia Minstrels were touring cities both in the United States and Europe.

Such blackface shows included comedy, dance, and popular music, typically performed by white men wearing black face paint and singing and speaking like stereotypical blacks. Indeed, the basis of such shows was the parodying of blacks, something that has made them anathema today. It also seems a bit strange today that such a widespread, popular form of entertainment could have at its heart such a narrow gimmick.

Minstrel shows typically consisted of three parts. In the first, the entire troupe sat on stage in a semicircle and sang popular songs such as “Camptown Races” or “Old Folks at Home,” and engaged in riddles, puns, and comedic one-liners. The second part, called the olio, was a variety show in which entertainers appeared and performed individually. The third part was a farcical skit that combined comedy and music in what was often a parody of current fads or events. A master of ceremonies, or interlocutor, usually oversaw the events of the show.

Among the best known minstrel acts of the age were the Christy Minstrels. Formed by Edwin P. Christy, this troupe played in New York City from 1846 until 1854 and helped popularize the songs of Stephen Foster.

Burlesque and vaudeville replaced minstrel shows as a popular form of variety show during the nineteenth century.

Minstrel shows dominated the American entertainment scene until long after the end of the Civil War. They reflected a preoccupation with slavery and the role of the freed black in society, and highlighted how racist much of white society was. As a form of entertainment, however, their days were numbered.

Variety Shows

Some impresarios saw a market for “clean” variety shows that left behind saloon environment and were suitable for women and children as well as men. One of these was Tony Pastor, the “father of American vaudeville,” who abandoned his career as a circus clown for the variety show business. In 1865, he opened his first variety theater in New York City, which specialized in wholesome acts and songs that poked fun at the upper crust, aspects that made his shows popular with working-class family people.

Burlesque

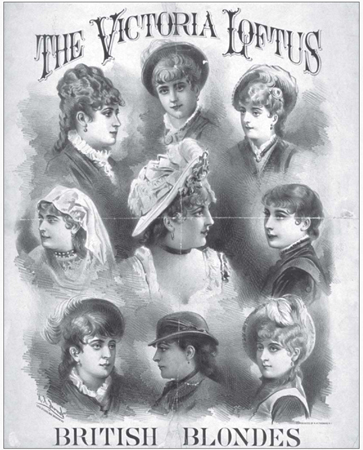

There was still a market for the off -color show, however. Burlesque shows began as comic parodies of well-known people or subjects, but steadily evolved into “girlie” shows that included provocative displays of the female form. One of the most famous of these was Lydia Thompson and her British Blondes, who brought their burlesques of classical drama to America in 1868. In this all-girl show, the women wore tights and short tunics when playing male roles, outfits that were considered very risqué at the time.

By the 1870s, American producers like M.B. Leavitt capitalized on the market for “burleycue” and “leg shows” by organizing female burlesque troupes who replaced parody with racy dance routines like the cancan. Before long, the buxom stars of these shows were being referred to as “burlesque queens.” Increasingly, however, male comedians were also added to the acts and developed comedy routines designed to appeal to the sorts of crowds who came to such shows.

Vaudeville

Vaudeville shows combined a variety of unconnected musical, dancing, comedy, and specialty acts and developed in the decades following the Civil War. To a large extent, they evolved from the olio, or variety portion of the minstrel show (minus, of course, the blackface). First built in the 1880s, vaudeville houses were ornate, opulent theaters with uniformed attendants where people of any class could feel like honored guests for an entry fee of 25¢.

Vaudeville, predecessor of the modern variety show, emerged in the 1870s as a popular form of urban entertainment and eventually came to replace the minstrel show. In its early years, however, it was widely considered a lewd form of entertainment for men only, and it was not until the 1880s that it became a popular form of family entertainment.

Stars

Like celebrities today, the theatrical stars of the nineteenth century were well-known and loved. Stage divas were also popular during the Civil War and the years following it, and many were as well-known and popular as celebrities today.

Most beloved of all was “Swedish Nightingale” Jenny Lind (1820–1887), a singer who appeared in every major European opera house between 1838 and 1849 and toured throughout the United States in the early 1850s, where she was lauded in the press. Other European stars, like William Charles Macready, were also well-known on both sides of the Atlantic, and frequently toured American cities during the mid-nineteenth century.

The New World also produced its own stars during this period. Edwin Forrest (1806–1872) was perhaps the greatest, and certainly the most popular, American tragic actor of the nineteenth century. Known for his arrogance, short temper, booming voice, and fierce looks, Forrest was famous for his many Shakespearean roles, especially Othello. He also offered prizes to encourage the writing of American plays and, as a result, had many roles created for him.

Stage divas were also popular during the Civil War and the years following it, and many were as well-known and popular as celebrities today.

CIVIL WAR Celebrities

Following are some of the most influential writers, entertainers, orators, and performers of the Civil War era, along with brief notations about their claims to fame. Many military leaders, politicians, and clergymen became well known during this era as well, and many of these are mentioned in their appropriate context elsewhere in this book.

» LOUISA MAY ALCOTT, author of Little Women.

» IRA FREDERICK ALDRIDGE, a free black from New York City, who became the first famous black American actor (albeit in Europe).

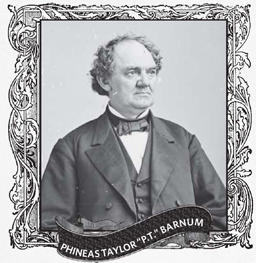

» PHINEAS TAYLOR “P.T.” BARNUM, an impresario and showman who ran the American Museum in New York City from 1841 to 1868 and who took his show on the road in the form of a huge travelling circus, museum, and menagerie in 1871.

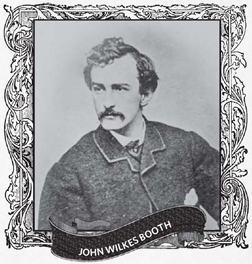

» EDWIN BOOTH, a popular stage actor and the manager of a theater in New York City (and brother of presidential assassin John Wilkes Booth).

» JOHN WILKES BOOTH, a popular stage actor whose fervent Southern sympathies promoted him to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.

» EDWIN P. CHRISTY, founder of the Christy Minstrels troupe of entertainers that played in New York City in the 1840s and 1850s.

» WILLIAM FREDERICK “BUFFALO BILL” CODY, who reflected his experiences as a soldier and bison hunter in his Wild West show starting in the 1870s.

» CHARLOTTE SAUNDERS CUSHMAN, a popular American stage actress from Boston.

» FREDERICK DOUGLASS, a free black orator and writer.

» AUGUSTA JANE EVANS, a prominent Southern author of nine novels.

» EDWIN FORREST, the most popular American tragic stage actor of the nineteenth century.

» STEPHEN FOSTER, a popular American songwriter.

» JOICE HETH, an aged black slave who P.T. Barnum purchased in 1835 and then exhibited as the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington.

» M.B. LEAVITT, an impresario who specialized in burlesque shows.

» JENNY LIND, the “Swedish Nightingale,” an opera singer.

» WILLIAM CHARLES MACREADY, an English stage actor who was popular in both Europe and America.

» TONY PASTOR, the “father of American vaudeville,” opened his first variety theater in New York City in 1865.

» JOHN BILL RICKETTS, an American circus proprietor.

» HARRIET BEECHER STOWE, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin.

» LYDIA THOMPSON, leader of the British Blondes troupe of burlesque entertainers, which came to America in 1868.

» MARK TWAIN, author of Innocents Abroad (1869) and numerous other books.

» JULES GABRIEL VERNE, the French author of science fiction classics like A Journey to the Centre of the Earth (1864), From the Earth to the Moon (1865), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), Around the World in Eighty Days (1873), and The Mysterious Island (1875).

» MAJ. GEN. LEW WALLACE, author of Ben Hur: A Tale of the Christ (1880).

The British Blondes was a famous all-girl show in which women wore risqué costume of tights and short tunics.

Ira Frederick Aldridge (c. 1807–1867), a free black from New York City, became the first famous black American actor, albeit in Europe. In 1825, he debuted with an acting troupe in London as the African prince Oroonoko in The Revolt of Surinam. Nicknamed the “African Roscius,” he was also lauded for his roles as Othello, King Lear, and Macbeth. Aldridge was popular throughout Europe, especially in Germany, and became a British citizen in 1863.

Other well-known American actors of the day included Charlotte Saunders Cushman; Edwin Booth, who also managed his own New York City theater; and his brother, John Wilkes Booth, most famous today as the assassin of Abraham Lincoln.

Directors and Playwrights

As stage productions became more complex, they increasingly required a director, a role which arose in its modern incarnation during this period. While he or she might still have a leading part in a play, the director was also responsible for overseeing every aspect of its production.

Playwrights also enjoyed improved status during the nineteenth century. They increasingly acted in or directed their own plays, benefited from new copyright laws that protected their work in both the United States and Europe, and began to receive royalties.

Scenery and Lighting

New technology allowed for a revolution in lighting and scenery during the nineteenth century. By the 1820s, candles and oil lamps had been replaced by gaslights in many theaters, and spotlighting effects through the use of limelight and the carbon arc were common by the 1850s. Many theaters were also fully trapped or even had hydraulic lifts, as did Edwin Booth's theater, allowing scenery to either be raised from below the stage or “flown in” from above.

Costumes, props, and settings also reached a high level of realism and historical accuracy during this period, especially in renditions of plays with historical underpinnings, such as those of Shakespeare. Scenery had traditionally been simply painted on flats, a practice that gave way to elaborate settings, such as sinking ships, falling trees, and erupting volcanoes. Such elaborate sets often required a long period between scenes to set up. Real animals — ncluding dogs, horses, and even elephants — joined human actors on stage. Other innovations of the era included completely enclosed, or “box” sets, often adopted for comedies, and moving panoramas to give the illusion of movement or travel.

Such elaborate production values meant that long-running plays also became increasingly common. As a result, the repertory system, in which theaters changed their performances almost nightly and under which a single theater might present dozens of plays in a single season, was largely supplanted.

Circuses and Carnivals

Circuses of all sizes, both travelling and stationary, were increasingly elaborate and popular forms of entertainment during the mid-nineteenth century.

Traveling circuses with three rings and a bigtop became increasingly popular during the nineteenth century, and largely replaced permanent, indoor circuses.

Travelling Circuses

Tent circuses started in America around 1830 and reached their peak in the early 1880s with the great traveling shows of Barnum and Bailey. Carnivals, smaller affairs that included games, rides, and sideshows, also existed and increasingly began to set up camp in conjunction with state and county fairs.

American circuses typically featured three rings, with individual acts playing simultaneously in each of them. In between the rings and to the sides of them were platforms for additional displays. Surrounding all of these staging areas was a large hippodrome track used for pageants, parades, and races.

Despite the familiar term “three-ring circus,” American circuses could actually have anywhere from two to seven rings; many, few or no additional platforms; and lack the usual hippodrome track. In Europe, the multi-ring circus never really caught on, and most retained a single ring.

Indoor Circuses

During the nineteenth century, many circuses were housed within permanent, roofed buildings and did not travel from place-to-place. Among such indoor circuses were the amphitheaters of John Bill Ricketts in America, Astley's in England, and the Cirque Olympique in Paris.

In addition to the ring, many of these circuses had large scenic stages used for presenting spectacular theater dramas that included horses and other animals.

Circus Acts

Prior to and during the early part of the nineteenth century, circus programs consisted largely of trick horsemanship performed by costumed entertainers within large circles, or rings.

Horses in such acts were trained to gallop within a circle at a constant speed, allowing a standing rider to maintain his or her balance by leaning inward slightly and making use of centrifugal force. To this basic act many variations were added, such as standing astride a pair of running horses, riding with one foot on the horse's head and the other in the saddle, and balancing head-downward in the saddle while firing a pistol at a target.

More sophisticated acts included somersaults from one horse to another, human pyramids upon several galloping horses, pantomimes, and pas de deux between partners. Female trick riders were also extremely popular during this period, leaping over broadcloth banners and through paper-covered hoops.

In between such strenuous acts, a “clown to the ring” performed acrobatic feats and comedy to give the riders and their mounts a needed rest.

In the years prior to and following the Civil War, trick horsemanship began to decline and was increasingly replaced with dressage and routines in which several matched, unmounted horses executed various evolutions at the behest of a trainer, rather than a rider.

During this period, many sorts of new, non-equestrian acts were also added to the circus, such as the flying trapeze. Wild animal acts also began to appear in circuses, performed by “lion kings” and “lion queens” and caged animals.

One of the most popular features of traveling circuses in the years following the Civil War was the exotic spectacle of the street parade, performed by a circus as it came into town. Such parades included brass bands; elephants; brilliantly painted, carved, and gilded wagons; and costumed entertainers mounted on horses or in chariots, all to the sounds of a calliope.

America's most famous circus bears the name of and owes much of its success to Phineas Taylor Barnum (1810–1891), perhaps the most famous of all American showmen. In 1835, the self-proclaimed “Prince of Humbugs” launched his career as a showman with the purchase of slave Joice Heth, an aged black woman who he exhibited as the 161-year-old nurse of George Washington.

From 1841 to 1868, Barnum ran the American Museum, one of New York City's most popular attractions, a museum and menagerie that was home to thousands of curiosities, freaks, and wild animals. And in 1871, Barnum took his show on the road, in the form of a huge traveling circus, museum, and menagerie.

Fairs and Expositions

Some of the most popular events of the nineteenth century were great national or international exhibitions showcasing culture or technological advancements. Among the greatest of the century were those held in the United States in 1876 (in celebration of the Centennial) and 1893, in England in 1851, and in France in 1855, 1878, and 1889. Scientists, captains of industry, arms manufacturers and futurists like H.G. Wells and Jules Verne were among the luminaries at such events.

In the United States, such fairs included all the elements of carnivals. For example, entertainers formed a kind of midway outside of the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial, America's first exposition. Likewise, state and county fairs, originally intended to promote trade and agricultural education, gradually began to include carnival amusements.

Tobacco and Other Vices

Partaking of tobacco and liquor were two of the ways soldiers and sailors on both sides passed the time and distracted themselves from the rigors and anxieties of military life.

Smoking and chewing tobacco were widespread among the soldiery and beloved pastimes for many. In the late 1840s, U.S. Army soldiers had returned from the Mexican War with a taste for the richer, darker tobacco of South and Central America, leading to an increased demand for cigars and other tobacco products, which in turn stimulated a U.S. tobacco industry.

During the Civil War, tobacco rations were given to both Union and Confederate soldiers, and many Northerners were introduced to tobacco this way. During Sherman's 1864 march across Georgia, Union soldiers attracted to the mild, sweet “bright” tobacco of the South raided warehouses for chewing tobacco. Some of this bright tobacco made it back to the North, where it became extremely popular among tobacco users.

Shortages of tobacco constantly threatened to deprive soldiers of these pleasures, and a great many letters home include requests for tobacco. Tobacco was one of the few shortages to hit the North more profoundly than the South because it was produced primarily in Confederate, rather than Union, states. Union soldiers often compensated for this shortage by trading Confederate soldiers coffee or other items rare in the South for tobacco.

IN PRAISE OF THE PIPE

IN PRAISE OF THE PIPE

Contemporary diaries are replete with references to tobacco use, most of them positive, as is this example: “Who can find words to tell the story of the soldier's affection for his faithful root-briar pipe! As the cloudy incense of the weed rises in circling wreaths about his head, as he hears the murmuring of the fire, and watches the glowing and fading of the hour pervading his mortal frame, what bliss! And yonder sits a man who scorns the pipe — and why? He is a chewer of the weed. To him, the sweetness of it seems not to be drawn out by the fiery test, but rather by the persuasion of moisture and pressure.” — John D. Billings, Union soldier

TRADING FOR TOBACCO

Following is an excerpt from the Civil War journal of Harry M. Kieffer — often referred to as Recollections of a Drummer Boy — who served for three years as a drummer boy with the Union forces. This entry was written during the summer of 1864 during the siege of Petersburg, Virginia, and describes one of the ways men on the opposing sides would obtain commodities from each other.

“It was no unusual thing to see a Johnny picket — who would be posted scarcely a hundred yards away, so near were the lines — lay down his gun, wave a piece of white paper as a signal of truce, walk out into the neutral ground between the picket-lines, and meet one of our own pickets, who, also dropping his gun, would go out to inquire what Johnny might want to-day.

‘Well, Yank, I want some coffee, and I'll trade tobacco for it.’

‘Has any of you fellows back there some coffee to trade for tobacco? Johnny Picket, here, wants some coffee.’

Or, may be he wanted to trade papers, a Richmond Enquirer for a New York Herald or Tribune, ‘even up and no odds.’ Or, he only wanted to talk about the news of the day — how ‘we 'uns whipped you 'uns up the valley the other day;’ or how, ‘if we had Stonewall Jackson yet, we'd be in Washington before winter;’ or may be he only wished to have a friendly game of cards!

There was a certain chivalrous etiquette developed through this social intercourse of deadly foe-men, and it was really admirable. Seldom was there breach of confidence on either side. It would have gone hard with the comrade who should have ventured to shoot down a man in gray who had left his gun and come out of his pit under the sacred protection of a piece of white paper. If disagreement ever occurred in bartering, or high words arose in discussion, shots were never fired until due notice had been given. And I find mentioned in one of my old army letters that a general fire along our entire front grew out of some disagreement on the picket-line about trading coffee for tobacco.

The two pickets couldn't agree, jumped into their pits, and began firing, the one calling out; ‘Look out, Yank, here comes your tobacco.’ Bang!”

The Tobacco Industry

In 1849, in the aftermath of the Mexican War (1846–1848), John Edmund Liggett established the J.E. Liggett and Brother tobacco company in St. Louis, Missouri, and others soon followed. In 1852, matches were introduced, making smoking immeasurably more convenient. By 1860, nearly 350 tobacco factories existed in Virginia and North Carolina alone, virtually all of them producing chewing tobacco. Only a half dozen of them produced smoking tobacco, manufactured as a side product from scraps left over from plugs.

Cigarettes, originally a Turkish innovation, had for some years been imported by English tobacconists. In 1854, however, London tobacconist Philip Morris began making his own cigarettes, and Old Bond Street soon became the center of the retail tobacco trade. Manufactured cigarettes appeared in America in 1860, a popular early brand being Bull Durham, and, in 1864, the first domestically-produced cigarettes were manufactured.

Tobacco was big business by the eve of the Civil War. An example of the industry's wealth is when Lorillard wrapped $100 bills at random in packages of Century cigarette tobacco to celebrate the hundredth anniversary of their firm in 1860.

In 1862, the U.S. government capitalized on the lucrative nature of tobacco and imposed a tax on it to help fund the war efforts, realizing about $3 million in revenue by the end of the conflict. In 1863, to help facilitate taxation, the U.S. Congress passed a law calling for manufacturers to create cigar boxes on which IRS agents could paste Civil War excise tax stamps, a law that inspired the beginning of cigar box art. In 1864, Congress levied the first cigarette tax.

Tobacco use continued unabated after the Civil War. From 1865 to 1870, for example, there was a growing demand in New York City for exotic Turkish cigarettes, which prompted tobacconists to seek skilled tobacco rollers from Europe. And, in 1873, Myers Brothers and Company marketed Love tobacco with a theme of North-South Civil War reconciliation.

In 1875, R.J. Reynolds founded R.J. Reynolds Tobacco Company and began producing chewing tobacco, including such brands as Brown's Mule, Golden Rain, Dixie's Delight, Yellow Rose, and Purity. Also in 1875, Allen and Ginter began including picture cards in their cigarette brands, Richmond Straight Cut No. 1 and Pet, to stiffen the packs and serve as premiums, something that was a big hit with smokers. Themes included “Fifty Scenes of Perilous Occupations” and “Flags of All Nations,” as well as boxers, actresses, and famous battles. The cards were a huge hit with customers. The same year, the company also offered a reward of $75,000 for development of a functional cigarette-rolling machine.

Indeed, at the 1876 Centennial Celebration in Philadelphia, Allen and Ginter's cigarette displays were so impressive that some contemporary writers thought the exposition marked the birth of the cigarette.

Opponents of Tobacco

Tobacco use was not, however, universally enamored. In 1836, Samuel Green wrote in the New England Almanack and Farmer's Friend that tobacco was a poison lethal to men and insects alike (it was often used as an insecticide component), in addition to being filthy. And an 1859 tract by Rev. George Trask, called “Thoughts and Stories for American Lads: Uncle Toby's Anti-Tobacco Advice to His Nephew Billy Bruce,” said that “physicians tell us that twenty thousand or more in our own land are killed” every year by tobacco.

In the nineteenth century, contemporary doctors widely recognized tobacco as a health threat.

Indeed, contemporary doctors widely recognized tobacco as a health threat, as evidenced by an 1845 letter of John Quincy Adams, who wrote that “in my early youth I was addicted to the use of tobacco in two of its mysteries, smoking and chewing. I was warned by a medical friend of the pernicious operation of this habit upon the stomach and the nerves.” And in 1856 and 1857, there was a running debate among the readers of the British medical journal Lancet about the health effects of tobacco (which ran along moral as well as medical lines, with little substantiation on either side).

Some military diarists complained of how filthy camps became when a preponderance of men chewed tobacco and of the noxious quality of the smoke. There were also social movements, akin to the temperance movements, that decried the use of tobacco in pamphlets that were distributed to soldiers.

Ulysses S. Grant himself died of throat cancer, likely caused by his chronic cigar smoking, at age sixty-three in 1885.

Alcohol

“No one agent so much obstructs this army,” wrote Maj. Gen. George McClellan, “as the degrading vice of drunkenness.” Complete abstinence among the troops, he continued, “would be worth fifty thousand men to the armies of the United States.”

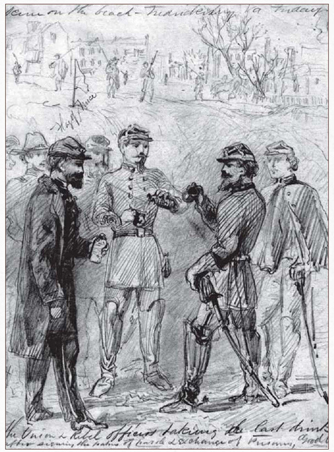

Union and Confederate officers have a drink together before prisoners were exchanged, in this drawing by Arthur Lumley. Many artists sketched the battlefields of the war.

Indeed, a high number of insubordinations, camp brawls, sexual assaults, and other crimes involved alcohol, as indicated by letters, diaries, and official U.S. Army court marshal proceedings. Many other distasteful episodes from the war also involved drinking to excess. For example, on July 30, 1864, Union Brig. Gen. James H. Ledlie hid behind the lines in a bombproof shelter while the troops of his division were massacred in the “Crater” outside of Petersburg, Virginia. Desperately seeking orders, some of Ledlie's subordinate officers eventually found him, drunk in his hide-away. And Ulysses S. Grant, Lincoln's champion general in the final phase of the war, had himself been forced out of the Army in 1854 on account of his heavy drinking.

An unfortunate result of the proliferation of prostitution is that at least one in ten Union soldiers suffered from some sort of venereal disease during the war.

Military personnel obtained alcohol at saloons when near towns and from sutlers when in the field, and were even issued it on occasion.

“Someone at headquarters got the idea that a quantity of whisky issued to each man in the evening would be beneficial to the general health of the men,” wrote John M. King, a soldier with the 92nd Illinois Volunteer Infantry Regiment, in describing one such episode. “There was not enough given each man to make him drunk … but there was just enough to make the men boisterous, excitable, talkative, and foolish. After the drinks there was a sort of pandemonium in nearly every tent.”

When soldiers could not buy alcohol or did not receive it with their rations, they would make it, and gave names like “Bust-Head,” “Nockum Stiff,” “Oh! Be Joyful,” “Pop Skull,” and “Tanglefoot” to such bootleg liquor. Ingredients in one included “bark juice, tar-water, turpentine, brown sugar, lamp-oil, Northern recipe for bootleg liquor included “bark juice, tar-water, turpentine, brown sugar, lamp-oil, and alcohol.” Southern recipes had similar ingredients and sometimes called for the addition of a piece of raw meat, which, after fermentation for a month, produced “an old and mellow taste,” in the words of one veteran.

Prostitution

Despite the overt moral prudishness of the day, prostitution existed during the era of the Civil War and then blossomed with its outbreak. Soldiers and sailors, far from home and family, frequently engaged the services of prostitutes.

An unfortunate result of the proliferation of prostitution is that at least one in ten Union soldiers suffered from some sort of venereal disease during the war, and a similar proportion was likely among personnel in other services and in the Southern forces. And in an age before the introduction of antibiotics, the effects of such diseases could be terrible.

Brothels were available in urban areas and common in places with high concentrations of troops, especially in the national capitals. In Washington, DC, in 1863, there were more than 450 brothels employing more than seven thousand prostitutes. And in Richmond, Virginia, streetwalkers openly plied the streets, going so far as to solicit customers in the very shadow of the Capitol.

Prostitution was often considered an activity plied by theater actresses, although this perception was probably more widespread than whatever reality on which it was based. On the other hand, there are many documented cases of young women being forced into prostitution after finding they were unable to support themselves at low-paying jobs as clerks or factory workers. With so many prostitutes operating in heavily populated areas during the Civil War, prices tended to be competitive, and $3 or $4 for a session was not uncommon.

Terms

BIRDCAGE (CHUCK-A-LUCK, SWEET CLOTH): A game of chance in which players placed bets on what numbers would appear on a trio of dice rolled from a cup or contained within an hourglass-shaped container.

BURLEYCUE: A popular name for burlesque shows.

CALLIOPE: A set of steam-powered brass whistles operated by a keyboard or a pin-and-barrel mechanism that imitated the sounds of a train locomotive whistle. With sound that could carry up to twelve miles, the calliope was intended to attract attention rather than play music, and it was a familiar feature of circuses, fairs, and riverboats. It was invented by J.C. Stoddard in 1855 in Worcester, Massachusetts.

CRIBBAGE: A card game for two or more players that involves playing and grouping cards into specific combinations and which uses a special board, typically fitted with holes to accommodate pegs, for scorekeeping.

DRESSAGE: The execution of precision movements by a highly-trained horse in response to nearly imperceptible signals from its rider.

LEG SHOWS: One of the nicknames given to burlesque shows.

PAS DE DEUX: An intricate dance or other entertainment routine intended for two performers. Taken from the French and its original application to ballet.

PRISONER'S BASE, PRISON BASE: A game played by children since at least the 1840s. Each of two teams has a home base that players are sent to after being tagged or otherwise caught and from which they can be freed only in some specified way.

THROWING THE PAPERS: A slang term that meant to play cards.

VOLTIGE: A form of trick riding that involved a rider leaping on and off a moving horse.