BEAUTY AND TOOKIE

They were quite a pair, Beauty and Tookie. They were inseparable; indivisible, really, never more than a few inches apart, never out of one another’s sight. In behavior and size and color and affect they were so well matched that sometimes they appeared to be one hen and a mirror rather than two distinct living beings. Often I wondered if they were sisters. Do chickens have sisters? So many chickens are probably at least half-sisters (one rooster being Father to Millions, I’m sure) that consanguinity might not count for much, or at least it couldn’t have been the only reason for their profound connection.

At the time, I had just moved to the countryside and had been stricken, as are many newcomers to country living, with the desire to have livestock. I didn’t want anything that might bite me or eat my car, so goats were out of the question. Cows seemed too demanding. Chickens, though, were the right size and level of maintenance for a novice farmer. I ordered them online, as any modern farmer would, and, thinking it might be wise to just dip a toe into chicken husbandry rather than taking a deep dive, I wanted to start with just one. But chickens don’t come in ones. If you order them online to be delivered via the U.S. mail, they come in twos or sixes or twentyfives, because a lone chicken in a postage box is not a happy chicken: it’s a cold chicken and, given the realities of long-distance transit, a very jostled chicken. Multiples keep each other warm, and serve as a kind of living bubble-wrap, cushioning each other against the wear and tear of travel.

So I ordered four. I felt like a real farmer. When they arrived, I immediately wanted fifty. Never having been much of a bird person, I was surprised to find I was very much a chicken person. I couldn’t believe how interesting and funny they were, with their mechanical-looking movements and serious expressions and chattering sociability. They marched around, all business, scratching the dirt, perusing the sky, muttering to themselves as they searched each vector of the yard for tidbits. They seemed to find me interesting, too, and whenever I came out to my garden, they made their way over to watch me—they didn’t come as close as a dog might, but close enough that it was clear they wanted to keep me company.

I got four—Beauty and Tookie and two more Rhode Island Reds whose names I have now forgotten. You can probably guess this isn’t a happy story. I took care of my girls, and locked them in their little coop at night. I pictured danger in the form of hawks, weasels, foxes, raccoons. I didn’t consider my neighbors’ fat old mutts a threat, because they were so lazy they could barely be roused to bark at the mailman. I lived up a steep hill, and as far as I knew these dogs had never bothered to cross the street, let alone tromp up my hill. I will spare you the full story, because I don’t like thinking about it—suffice it to say that very soon after I got my four chickens, I had only two left.

Nevertheless, it was a happy farmyard for quite some time. I added chickens. I added turkeys. One day, on a drive to the drugstore to get some shampoo, I drove past a “Guinea Fowls for Sale” sign that called to me, and I came home with L’Oréal and guineas. I took in some ducks from a neighbor who felt he was “overducked.” I woke up one morning to find I had Sebastopol geese—beautiful, vociferous, angry creatures—dropped off by a friend who thought I’d like them. My sweethearts were still Beauty and Tookie, maybe because they had been my firsts, and maybe because they delighted me by their harmony. Chickens can be bitchy and sometimes vicious to each other. They sometimes will murder a new addition to the flock, and if they detect that a bird in their midst is sick or injured, they will dispatch with it. Everyone thinks they’re stupid, but they seemed shrewd to me. They keep their world well ordered, whatever it takes.

I noticed one day that Beauty was losing weight. She and Tookie always slept together and came out of the coop together side by side for their morning constitutional, but that morning Beauty stayed behind in the nest. It was strange. I scooped her up and brought her outside, placing her next to Tookie, but her legs crumpled under her and she sat in a heap on the grass. The next day, I took her to my vet, who sent me home with antibiotics, but warned me that he really didn’t know what was wrong with her. I dutifully tucked the pills into her beak and drizzled water in with an eyedropper, but she still didn’t move, and when I picked her up, her body felt like a puff of air in a tiny cage of bones.

I wouldn’t have blamed Tookie if she’d done what chickens naturally do—or at the very least if she had abandoned Beauty as she sat, day after day, on her little mat of hay, her eyes getting milky and her comb growing pale. But until Beauty died, Tookie came in every night and took her place next to her, as if nothing had changed and the two of them were still a pair, patrolling the yard; cocking their heads in perfect synchronicity when the spiky shadow of a circling hawk passed over them; muttering their secrets to each other—my lovely girls, twinned, entwined, as they settled into their nest, warming each other as the night air cooled and darkness closed in.

{© 2015 Susan Orlean}

Maui, Hawaii, 2014

Maui, Hawaii, 2000

Evanston, Illinois, 2011

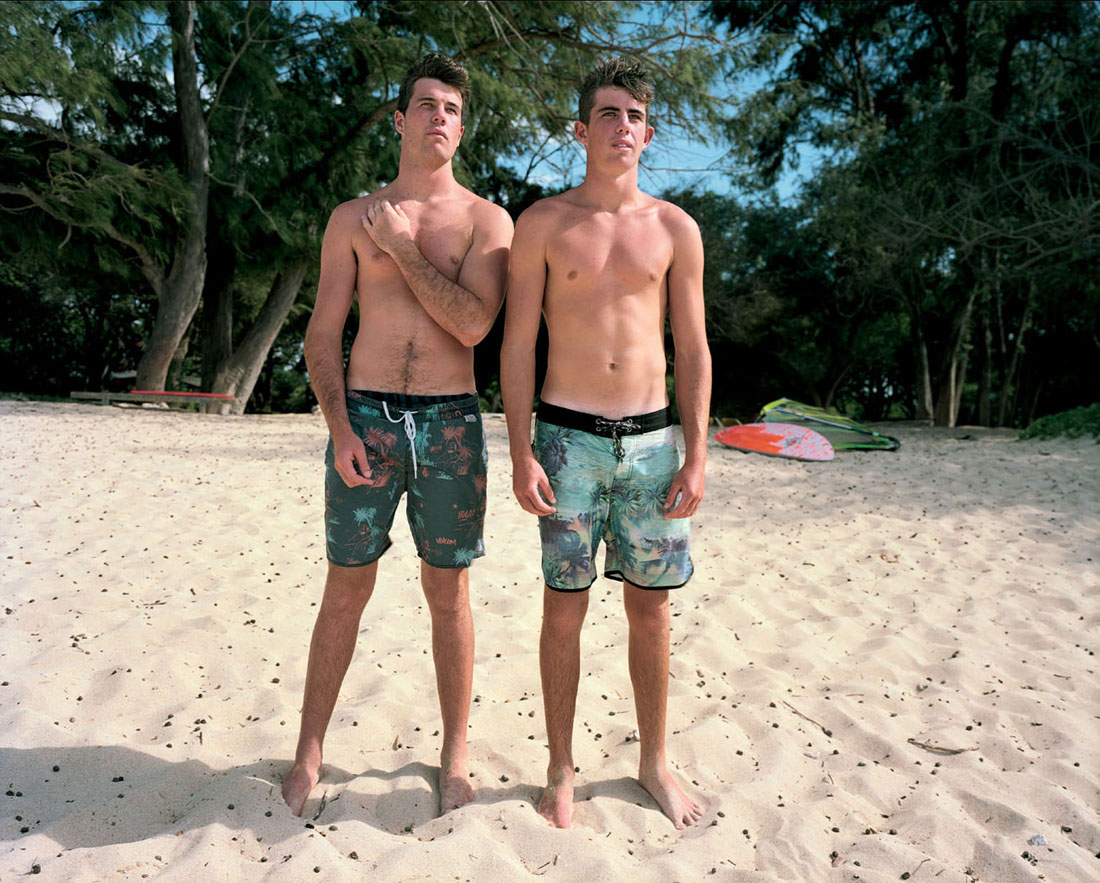

Maui, Hawaii, 2014

Maui, Hawaii, 2013

Maui, Hawaii, 2013

Evanston, Illinois, 2005

Maui, Hawaii, 2011