SANTA MARIA GLORIOSA DEI FRARI

A masterpiece of Venetian Gothic ecclesiastical architecture, this cavernous 15th-century church for Franciscan friars took more than 100 years to complete, along with its “brother” SS Giovanni e Paolo, and a further 26 years for the consecration of the main altar. A wonderful series of art treasures is held within the deceptively gloomy interior, which is almost 100-m (330-ft) long and 50-m (165-ft) across, from priceless canvases by Titian and Bellini to tombs of doges and artists such as Canova.

Majestic façade of Santa Maria Gloriosa dei Frari

NEED TO KNOW

![]() Campo dei Frari, San Polo • 041 275 04 62 • www.chorusvenezia.org • Open 9am–6pm Mon–Sat, 1–6pm Sun (last admission 30 min before closing time); closed 1 Jan, Easter, 15 Aug, 25 Dec • Adm €3; Chorus Pass €12 (includes admission to 18 churches)

Campo dei Frari, San Polo • 041 275 04 62 • www.chorusvenezia.org • Open 9am–6pm Mon–Sat, 1–6pm Sun (last admission 30 min before closing time); closed 1 Jan, Easter, 15 Aug, 25 Dec • Adm €3; Chorus Pass €12 (includes admission to 18 churches)

- There are some great cafés and eateries in Campo dei Frari.

- Enjoy the nativity scene with lighting effects and moving figures at Christmas.

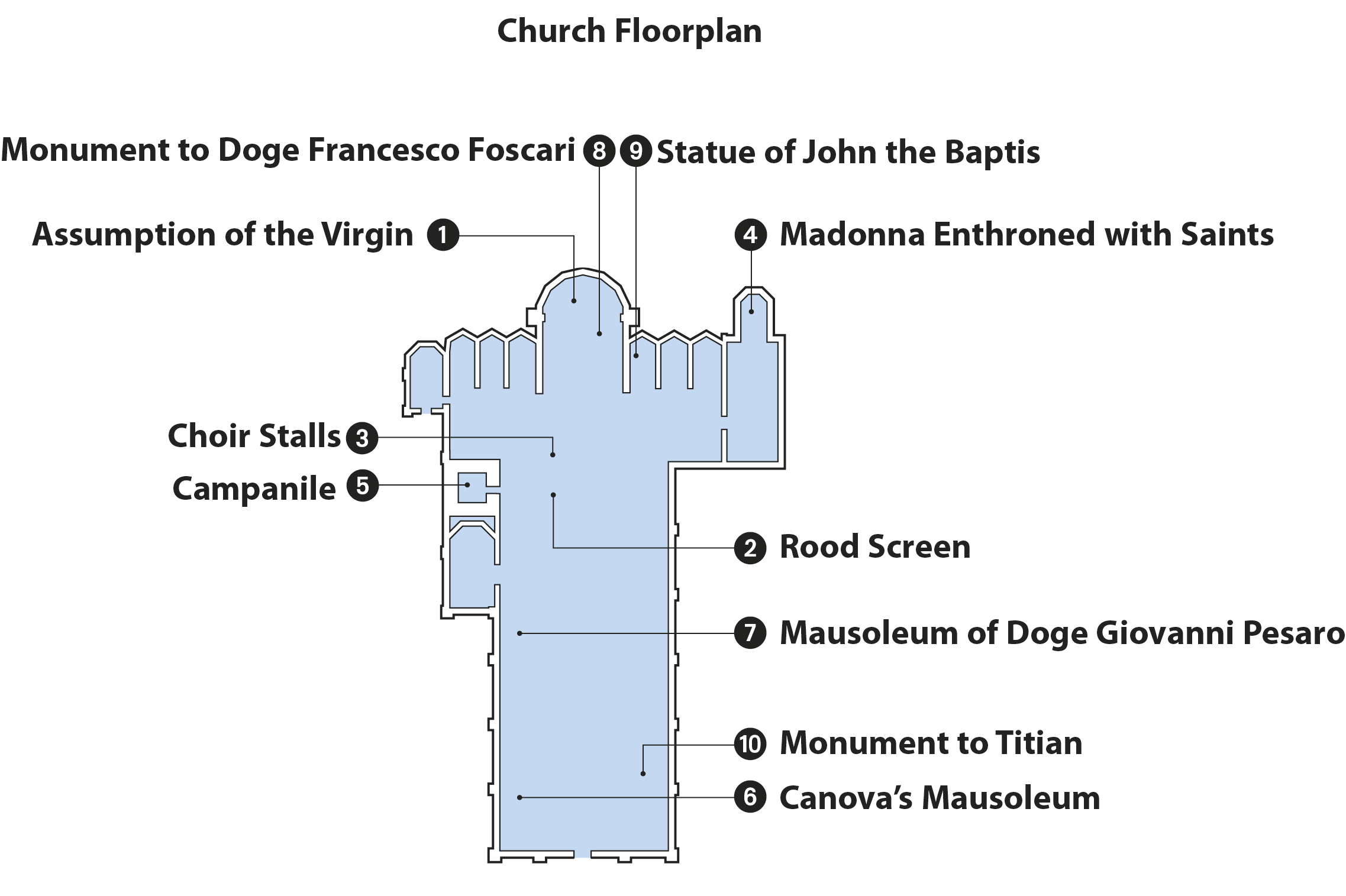

1. Assumption of the Virgin

Titian’s glowing 1518 depiction of the triumphant ascent of Mary shows her robed in crimson accompanied by a semicircle of saints, while the 12 apostles are left gesticulating in wonderment below. This brilliant canvas on the high altar is the inevitable focus of the church.

Titian’s Assumption of the Virgin

2. Rood Screen

This beautiful screen, which divides the worship area and nave is carved in a blend of Renaissance and Gothic styles by Pietro Lombardo and Bartolomeo Bon (1475). It is also decorated with marble figures.

Screen dividing the worship area and the nave

3. Choir Stalls

Unique for Venice, the original three tiers of 124 friars’ seats deserve close examination for their inlaid woodwork. Crafted by Marco Cozzi in 1468, they demonstrate the influence of northern European styles.

4. Madonna Enthroned with Saints

Tucked away in the sacristy, and still in its original engraved frame, is another delight for Bellini fans (1488). “It seems painted with molten gems,” wrote Henry James of the triptych.

5. Campanile

The robust 14th-century bell tower set into the church’s left transept is the second tallest in Venice.

6. Canova’s Mausoleum

This colossal monument, based on Canova’s Neo-Classical design for Titian’s tomb, which was never built, was a tribute by the sculptor’s followers in 1822.

Canova’s Neo-Classical design for Titian’s tomb

7. Mausoleum of Doge Giovanni Pesaro

The monsters and black marble figures supporting the sarcophagus of this macabre Baroque monument prompted art critic John Ruskin to write “it seems impossible for false taste and base feeling to sink lower”.

8. Monument to Doge Francesco Foscari

This is a fine Renaissance tribute to the man responsible for Venice’s mainland expansion. Foscari was the subject of Lord Byron’s The Two Foscari, which was turned into an opera by Verdi.

9. Statue of John the Baptist

The inspirational wood statue of John the Baptist from 1450, which was created especially for the church by artist Donatello (1386–1466), stands in the Florentine chapel. The striking emaciated carved figure is renowned for being particularly lifelike.

Wood statue of John the Baptist

10. Monument to Titian

Titian was afforded special authorization for burial here after his death during the 1576 plague, although this sturdy mausoleum was not built for another 300 years.

STATE ARCHIVES

The labyrinthine monastery and courtyards adjoining the church have been home to Venice’s State Archives since the fall of the Republic. Its 300 rooms and approximately 70 km (43 miles) of shelves are loaded with precious records documenting the history of Venice right back to the 9th century, including the Golden Book register of the Venetian aristocracy. Scholars enter the building via the Oratorio di San Nicolò della Lattuga (1332), named after the miraculous recovery of a Procurator of San Marco thanks to the healing qualities of a lettuce (lattuga).