Oren’s farm went to the bank for mortgages. The little that was left over had to be spent on his old debts. Mark saw the farm go without regret. With its burned buildings, black skeleton tree, and eroded gully full of debris, it seemed to stand for all the castoff wretchedness of his past life. Let it go, thought Mark, let it all go. I never want to see it again as long as I live.

“The livestock, though,” Father said. “It all belongs to you now. You were Oren’s only relative as far as we can find out. You now have seven cows, a team of work horses, a pretty good Hampshire boar and sow, and sixteen pigs and some chickens. Also some dilapidated farm machinery. What shall we do with it all?”

“Could I make you a present of a cow or two, Mr. Melendy?” offered Mark, as if he were proffering chocolates. “How about the pigs too? I’d like it fine if you’d take ’em all!”

“Nobody ever offered me a cow before,” replied Father thoughtfully. “I’d like a few, very much. There’s not enough heavy work on the place for a team, though, and I don’t honestly think we need pigs. Perhaps Willy would be grateful for some more hens.”

So after that there were three cows at the Four-Story Mistake. They lived in the stable with Lorna Doone, Persephone the goat, and her daughter Persimmon. In the morning, after milking, Rush or Mark drove them out to pasture. In the evening Oliver fetched them home again. From lean cows with peaked joints and barrel-stave ribs they became round, queenly cattle with a dignified and measured gait. Their bells tinkled all day long, and from time to time a distant sound of mooing could be heard, as if someone were blowing into a conch shell.

As for the remaining Meeker livestock, it was Mona who thought of what to do about them. “Auction them,” she suggested. “But let’s auction them here. We’ll have—I know!—We’ll have a kind of fair. We can have a show, maybe, and sell something or other; for the benefit of the Red Cross, or something. (Except Mark’s cow money, he’ll need that for himself, of course.)”

Everyone thought this was a splendid idea, combining all the best features of business, pleasure, and good deeds. The date was set for the middle of September, a Saturday. Father promised to come home for it.

For his three weeks’ vacation was at an end. His bags were packed, his briefcase dusted off and bulging with its own importance once more. Also he was returning to his labors with an added six pounds of weight and a healthy tan.

“If only you could always be here,” sighed Mona, her cheek against Father’s scratchy sleeve. “We’d all have such a good time, and you’d never get that green, crumpled look again.”

“Green, crumpled look, eh?” said Father. “Must be what they call Pentagon Pallor. Ah, well, one must sacrifice something even if it’s only beauty.”

“Father, you’re so silly,” Mona said, and gave him a hug.

It was sad to have him go. It was always sad. But this time they had many things to occupy their minds. There were plans for the Fair. And then there was school.

School began the day after Father left. The children looked different that morning. The girls wore clean sweaters and skirts. Everybody wore shoes and socks, their hair was brushed smooth for once, and all were clean. Isaac and John Doe prowled around the breakfast table distrustfully. “Where are they going now?” the dogs asked each other. “What is the matter with them? All their shoes smell of polish!”

After breakfast there was a tremendous lot of hurrying and dashing up and downstairs, and collecting pencil boxes and copybooks. At last they were ready. Willy drove the surrey around to the front and they all piled in.

Cuffy stood on the doorstep, issuing last-minute commands and admonitions. “Oliver, use your handkerchief when you need it. Mona, you see he drinks all his milk at lunch and see that Mark does too. Randy, stop leaning out like that. Rush, Rush, you didn’t take your sweater—”

But the surrey was halfway up the drive. “Too late now, Cuff!” called Rush, free as air.

“Lands, lands, them young ones!” muttered Cuffy, going into the house. How big it was, how empty. The air seemed still to ring from all the recent haste and noise.

Isaac sat down in a patch of sunshine and scratched at his ear with a loud, boney thumping. Then he went to sleep. Cuffy stood in the middle of the living room, lost in thought. Suddenly she turned, hurried to the broom closet in the hall, and dragged out the vacuum cleaner with a clatter. She couldn’t stand the silence.

But by the next morning she was used to it, and even rather liked it.

As for the children, their lives were frantically busy. At school there were new teachers, new classrooms, new faces, new books. And after school there was homework, and there were long, thrilling conferences about the Fair.

It was to be a Children’s Fair, Mona decided. Everything about it was to be done by children. She, and Daphne Addison, and all the girls they knew would bake cakes, cookies and candy, to sell. The boys would take care of putting up the decorations, building the booths, and so on. There were going to be grab bags too, and a fortune-teller, and a show. The Melendys adored giving shows.

In the afternoons when they came home they took their homework as if it were castor oil, gulping it down as fast as possible, and immediately afterward plunging into the important matter of the Fair.

Mona (who was to be the fortune-teller) wandered about with a Cheiro palmistry book, practicing on the palms of her family. She was always grabbing somebody’s hand and saying, “You’re going to live to be a hundred. You’ll always be safe in accidents. You’re going to have five children. Or do those lines mean that you’re going to be married five times?” And then she would look in the book to make sure.

“You have a good, even head line,” she told Willy Sloper. “And your heart line’s nice and steady, but this thing—well, I don’t know exactly what it is, but I know it means something extremely interesting. Just wait till I look it up in the book—”

“It means I peeled a potato the wrong way thirty years ago,” Willy said bluntly. “It’s a scar.”

Randy practiced dance steps for the show. She also painted posters. Already there was one in the Carthage post office, one in the school gymnasium, and another over at Eldred, in the bank.

AUCTION AND FAIR! [the posters said]

3 P.M. SEPTEMBER 18

FOUR-STORY MISTAKE.

LIVESTOCK TO AUCTION.

CAKE SALE AND CONCERT.

ENTERTAINMENT AND REFRESHMENTS.

COME ONE, COME ALL.

Tickets 50 cents. Benefit of Red Cross.

Oliver made the tickets. He cut them out of cardboard and printed the words “Admit One” on each, in colored crayon. He made so many of them that at night when he closed his eyes he kept seeing everywhere the words “Admit One.”

Rush and Mark did a lot of striding about with hammers and nails, though actually there was little to be built. Mona was going to use the summer house for her fortune-telling; the animals were to be tied up in the stable (except for the pigs, of course), and the Addisons had contributed two tents for outdoor booths. Still there were some boards in the stable, and Rush and Mark both liked to build, so they made a pavilion down near the brook; rather lopsided, it was, but large, and a splendid place for a cake sale.

“Decorations, though,” sighed Mona. “There’s nothing but crêpe paper, and not much of that. I even looked when I was in the city. And of course balloons are out of the question, and I suppose Japanese lanterns are unpatriotic, even if we could get them. So what shall we do?”

Their solution was given them, however. None of them ever knew who had whispered their problem into the benevolent ear of their old New York friend, Mrs. Oliphant, but one day, about a week before the Fair, a large box arrived for them.

“It’s awful light,” said Oliver dubiously, lifting it. “Awful light for anything so big, and it doesn’t rattle.”

“I wonder what it can be,” wondered Randy.

“The best way to find out is to open it,” said Rush, and swooped down on the cord with his scout knife.

There was a rapacious pulling and tearing, and a growl of torn cardboard.

“Look, here’s a note,” announced Rush, holding it up over his head where nobody could reach it. “No, let me read it out loud. Saves time. ‘Dear Children,’ it says. ‘I hear you are in need of decorations and am sending you these. I bought them in San Francisco’s Chinatown, years ago, because I knew, intuitively, that the time would come when I would surely need them to beautify a Livestock Auction. I wish I could be present on the momentous day, even though I could not promise to buy a cow or even a pig, since the apartment is crowded already. Much love to you all, including the new member of the family. Gabrielle DeF. Oliphant.’”

“Hooray for Mrs. Oliphant!” shouted Oliver. “Next to Cuffy she’s the nicest lady I ever saw.”

“And look at the decorations!” cried Mona.

Almost speechless, they carefully took them from the box. There were great, pleated garlands, and necklaces, and chains, all made of paper. They opened out like fabulous accordions, many feet long, and were most marvelous colors: green, turquoise, yellow, vermilion, magenta, purple. There were dozens and dozens of them, all different shapes and colors, and beautiful beyond the wildest fancy. There were gilded paper dragons, too, and fantastic, scowling fish, and curious masks. These were ornaments fit to fly from the minarets of Aladdin’s palace.

“Oh, brother,” said Rush. “This is going to be the prettiest Livestock Auction and Fair that anybody ever saw!”

“It mustn’t rain!” said Mona. She looked up at the sky severely. “It must not rain!”

As the day drew near, a sort of quivering excitement seemed to vibrate over the Four-Story Mistake, exactly as intense heat makes the air quiver above a prairie. Dozens of strange bicycles lay dead on their sides in front of the house each afternoon. Children were everywhere. There was a sound of hammering, of laughter, argument, and loud conversation. A smell of baking floated out of doors. Vast preparations were under way in the kitchen, though the cakes themselves had to be made at the very last.

There were difficulties, of course. Rush smashed his thumbnail with the hammer and worried for fear it would affect his playing. They could not agree as to the best place to give the show. Pearl Cotton, Trudy Schaup, and Margaret Anton had a terrible fight about who was going to make the orange layer cake. Mona settled that by saying they could each make one; there was no such thing as too many orange layer cakes. Randy burned up a whole pan of cake-sale hermits, and put too much vinegar in the vinegar candy; Rush said it tasted like congealed French dressing. But on the whole things went well, and it promised to be a memorable fair. They relaxed their restrictions against adults in the case of Mr. Titus who pleaded to be allowed to make some marble cakes, and in the case of Mrs. Wheelwright, of Carthage, who was famous for her jelly doughnuts, and, of course, in the case of Mr. Cutmold, who was the auctioneer.

“Everything is going marvelously,” sighed Mona, on Thursday.

But on Friday it rained. It rained all day. The children were no good in school. They kept staring out the windows, sighing gustily, and not hearing when their teachers called upon them.

Mona met Randy at recess. Her look of a tragedy queen was only slightly marred by the ink on her chin.

“We are ruined!” she said.

“Oh, listen, maybe it’ll clear up before morning.”

“No, it won’t, we’re ruined. Chris Cottrell says this is probably the equinoctial storm, and that it’s bound to last three days at least.”

“Well, I won’t believe it. Anyway, what is an equinoctial storm?”

“It comes at the times of year when days and nights are equal length; now, in September, and then again in March.”

“Oh.”

They listened to the rain in silence; then Randy said, “We can have the Fair indoors maybe.”

“Yes, certainly, a splendid idea. We’ll auction the cattle off in the living room, and the hogs in Father’s study. Yes, that’s a dandy idea!”

“Well, you don’t have to be so mean about it, I was only trying to think of a way,” said Randy, rather hurt.

“Okay, I know. But it’s just more than I can bear to think of all those lovely boxes of penuche, and puffed-rice candy, and fudge, going to waste, to say nothing of the dozens of cakes, and the Chinese decorations!”

The bell rang then, and they went back to their classrooms with despair in their hearts. The cakemaking after school lost all its allure, but the girls went through it grimly. Every time a cake was in the oven, and therefore in the hands of destiny, the children rehearsed their parts in the show, and perfected their plans. But all the preparations which should have been joyously festive were gloom-tinged instead. The wet wind sighed strangely in the screens, and the rain drove harder than ever against the windows.

“You ought to hear it up in the cupola,” Mark said. “It sounds like bullets.”

“Oh, I hate it!” cried Mona, half in tears. “Horrible, vile, pig weather! Why couldn’t it have held off?”

That night she lay in bed and listened to the roaring of the spruces. It’s nothing to get so upset about, she tried to tell herself. What’s an old fair, after all? It can be postponed. Think if it was Nazi bombers. Think if it was a storm in the South Pacific with only a tent over you. This isn’t anything, it’s less than anything at all. But, oh, I wish it would stop!

The world rocked like a cradle. After a while she fell asleep.

Why do I feel so blue? wondered Mona, when she woke up the next morning. My mind is full of something heavy and sad. What is it? Oh, the rain! She lay very still, listening. Holding her breath. She heard the loud, ruthless jeer of a bluejay; and then something else. A lawn mower! Mona’s eyes flew open, and she saw the early-morning sunlight pouring through the windows.

“Oh, thank you!” cried Mona, leaping out of bed. “Thank you, thank you, thank you!”

It was a glorious morning, full of glorious work to do. Willy ambled about with a ladder, pinning up the decorations while Mona directed from below. Mark groomed the cattle, and helped Rush mow the lawn. Randy and Oliver sat among heaps of tissue paper, doing up presents for the grab bag. Children kept coming down the drive bringing their contributions of homemade cake, candy, popcorn balls, cookies. Daphne and Dave arrived earliest of all to set up the tents, and remained for the rest of the day helping with every sort of job. Hammers rang and saws sawed. Dogs barked, cows mooed, pigs squealed or rumbled, according to their size, and above all, shriller than all, were the high-pitched, intense voices of the children.

It was a marvelous day: September at its best. Hot in the sunshine, and cool in the shade, and the sky above was deep, deep azure like a gentian. Here and there, already, a tree had changed its color. There was a maple red as cardinal feathers, and back in the woods the hickories were turning yellow; but everything else was green.

Lunch was a dreamlike meal of sandwiches eaten out of doors, absentmindedly, with work still in progress. Cuffy would allow no one in the kitchen. She was making enough punch to slake the thirst of regiments.

At one o’clock Father arrived in the only Braxton taxi. It was wonderful to see him, they were all delighted, but their embraces were brief, their greetings briefer, and he was pressed into service before he had time to change his clothes. In no time at all he was standing on a kitchen chair tacking cheesecloth up on the summer house.

By two o’clock the transformation was complete. The Four-Story Mistake had become a fairground, and beautiful it was. The Chinese streamers were gorgeously looped from tree to tree, twined about trellises, and draped over branches. The jovial fish and dragons danced in the light September wind, and colored masks were strung in unexpected places. The Addisons’ tents had been transformed from ordinary olive-drab backyard affairs to small Bedouin or Arabian shelters. Mona had done this by draping them with anything colorful and handy. A red tablecloth and a green hall rug for one. A yellow bedspread and Father’s purple dressing gown, with the sleeves turned in (and not without a certain amount of resistance from Father) for the other. The result was that the tents were hot as Tophet inside, but wonderful to look at.

At two-thirty the people began to arrive. Oliver and a friend of his, Billy Anton, sold tickets at a point halfway up the drive. They had two chairs, a change box, a small table, a beach umbrella and four bottles of pop, and did a thriving business. People arrived in dozens. Farmers came for the sake of the auction, and their children came for the fun.

The Melendys and their friends had provided quite a lot of fun.

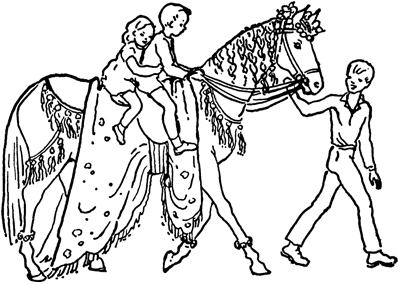

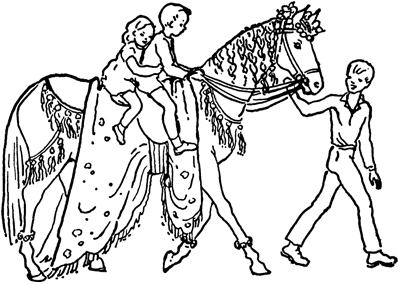

The Ten Cent Ride, for instance. Mark had thought that up himself. Most of the children who came to the Fair were farm children; the rest came from such small towns as Carthage and Eldred; a ride on the back of a tame, old mare was nothing new to them. But who had ever ridden on such a horse as this? For Lorna Doone had been decked out like a steed from King Arthur’s stables. Above her ears were bouquets of nasturtiums, her mane was braided with scarlet wool, and across her brow was a diadem of large glass beads. She wore a crimson saddlecloth with fringed edges, and little bracelets of bells jingled above her hoofs (they were really only the old elastic garters sewn with bells that Mona and Randy had used for Morris dancing in their city school).… Lorna Doone was a horse of graceful temperament, she submitted serenely to all these trappings, and as Mark led her up and down the drive, and along the path through the woods, each small child upon her back felt that he rode as a king, and remembered long afterward that glittering and chiming journey.

The fortune-teller’s booth was popular with people of all ages. The inside of the summer house was draped with blue cheesecloth left over from the show the Melendys had given in the winter, and pinned to it were stars and moons cut out of silver paper. There was a curtain across the door, and in the bluish gloom a table stood, on which were placed a round crystal paperweight, a candlestick, a rather sticky skull made out of plasticene, and a heavy book with an ornate binding which looked exactly like the book of a sorceress, but which once opened proved to be a compendium of the diseases of sheep. Still, nobody needed to know that.

Mona herself, after an inward struggle, had decided to sacrifice beauty for character, and was disguised as a very ugly, ancient soothsayer. She was wearing a wig of grey yarn, a costume which consisted of a long slip to which were pinned all the brightest scraps in Cuffy’s piece bag, as many bracelets as she could collect, and a shawl over her head. Her face was crisscrossed with hand-made wrinkles applied with an eyebrow pencil.

She read one palm after another. The customers kept pouring in, and the dimes poured with them. Mona warmed to her work.

“You are going for a long trip across water,” she might say, looking into the work-toughened palm of a farmer. “After the war’s over, of course, and I think it’s going to be Egypt. A trip up the Nile, maybe.” Or, gazing wickedly at the hand of one of her schoolmates, she might say, “A man is about to enter your life. He is dark and handsome, even though his voice is changing. It looks like Harold Rauderbusch to me…”

The customers loved it. They giggled self-consciously and shifted their feet, but they hung on to every word.

Randy and Daphne presided at the cake booth. What a lavish display that was! At least at first; it did not last long. There were the three orange layer cakes, and the angel food cakes, the chocolate, mocha, sponge, raisin, and spice; the cupcakes topped with pink, white and chocolate; the trays of hermits, brownies, myriad cookies, and many another delicacy. And, dominating all, were the majestic marble cakes contributed by Mr. Titus. The girls worked like beavers, for the demands were heavy; Daphne was terrible at making change, and Randy was clumsy at tying packages, and from their efforts to keep the flies at bay some of the cakes tasted of Flit, but between them the girls managed pretty well, shortchanging only the minister and a lady from Braxton, and giving out only one really insecure parcel; though that, unfortunately, had contained a dozen of Mrs. Wheelwright’s jelly doughnuts.

Punch was dispensed by Chris Cottrell in one of the Bedouin tents, and ice-cream cones by Trudy Schaup in the other. Even the two iron deer had been put to good use. Their antlers were twined with beads, paper streamers, and ribbons, and bound to the back of each were bulging saddlebags of brightly colored cloth. In front of the deer with the proudly raised head was a placard: “FOR BOYS! GRAB BAG! TEN CENTS A TURN!” And in front of the grazing deer was a similar proclamation for girls. The Melendys had worked hard over these gifts, and they were really good. In addition to the dime-store whistles, bubble pipes, puzzles, and bags of marbles, Oliver had contributed many of his small, precious, prewar metal planes and automobiles. Rush had surrendered a tiny, cherished flashlight, a harmonica, a pocketknife, and a cowboy belt set with colored stones. Randy had parted with two paintboxes, a set of crayons, and a white china pig. Mona’s contribution consisted mainly of ten-cent jewelry: rings and large, flashing pins. She had also generously given four tiny bottles of perfume, and a box of incense.

No wonder the grab bags were such a success. Paper and string littered the lawn, eager fingers tore apart little bundles, and Pearl Cotton at the girls’ deer and Jerome Hubbard at the boys’ were already beginning to wonder if the supply would hold out.

This was not all. There still remained the boat ride and the Treasure Tree.

Steve Ladislas had lent the Melendys his little homemade, flat-bottomed boat, and Dave Addison took small passengers on a thrilling tour of the swimming pool. Half the children had never even seen a boat before; they hung over the side, and trailed their fingers and screamed at the sight of minnows; a whole ocean could not have pleased them more.

The Treasure Tree was really nothing but the tree house dressed up. Still, more than half the children had never seen a tree house before, and they were well-satisfied with it, even though there was no treasure on hand, unless you counted Rush, who was in charge.

The Fair belonged to the children, first of all. They had taken it over. In the background their mothers watched, gossiped with one another, and sat in the cool shade, babies on their knees. Their fathers, the farmers, gathered about the table, talked, spat, waited for the auction to begin.

“Jeepers, who are those?” cried Randy suddenly, during a lull in business.

Lumbering slowly through the crowd appeared two men. They walked as if it were difficult for them not to walk on all fours. They wore dark old denim clothes, more brown than blue by now, and on their heads were denim caps with long, sharp visors. All you could see of each one’s face was eyes and nose: the rest was muffled in great waves of beard.

“Why, my goodness, they’re the Delacey brothers,” Daphne said. “They hardly ever come down out of the woods.”

“Rush told me about them,” Randy murmured. “I never really thought I’d see them.”

“Hardly anybody ever sees them,” said Daphne.

It was almost time for the auction. The cattle were all tied up outside the stable. The hogs were slumbering in one improvised pen; the melancholy Meeker poultry pecked and scratched in another.

At four o’clock Mr. Cutmold, the auctioneer, rang a large dinner bell. “Auction about to comm-ance!” he bellowed, in a voice that had been trained to volume. “Right over here, folks! Right over to the stable! Great opportunities for all!”

The crowd collected. Farmers to the front, of course, their faces grave: business was about to begin. Their wives came too, each with an identical pair of small children: one to carry, and one to hang on to. The other children deserted their pastimes at the sound of the bell, and joined the grown people. They pushed among the crowd, climbed bushes, and stood on railings. Rush came down out of his tree, Randy and Daphne left their cakes, the ancient gypsy stepped out of her booth with her wig on crooked, and Oliver and Billy Anton, prudently taking the money with them, deserted the box office on the principle that everybody who was coming must have come by now.

Mr. Cutmold was standing on an improvised auctioneer’s block which was actually the kitchen table. He had a gavel in his hand, and an upended orange crate to knock on. Willy Sloper had been delegated to assist Mr. Cutmold, and he now led out the first cow.

“Here’s a very fine little animal,” boomed Mr. Cutmold. “A fine little first-calf heifer; a grade Holstein, two years old,” and he proceeded to list her qualities and virtues. At the end he said. “What am I bid for this excellent creature?”

“Ten dollars,” said a farmer instantly.

“Ten dollars!” shouted Mr. Cutmold, as if he had been stung by a bee. “Ten dollars! Give her away, why not? Do I hear fifteen?”

“Fifteen,” said someone else.

“Kinda scrawny, ain’t she?” murmured the first farmer’s wife.

“I’ll fatten her up. Twenty dollars!” said the farmer boldly.

“Do I hear twenty-five?” sang Mr. Cutmold alluringly, standing on the tips of his toes, and rolling his eyes.

He did hear twenty-five. Before the heifer was sold he heard eighty dollars.

“Eighty dollars!” said Oliver. “When I grow up I’m going to be a cow raiser.”

“I’m going to be an auctioneer,” said his friend Billy Anton, gazing raptly at Mr. Cutmold. “I got a good big voice for it already.”

Willy led one of the older cows up to the auction block. She stood there staring dreamily at the crowd, her eyes like plums, and her jaws working with a slow, swiveling motion. Her tail flapped carelessly, arrogantly, at the September flies. She looked dignified and worthy of respect.

“Here we have a splendid animal,” enthused Mr. Cutmold. “A four-year-old grade Holstein. An excellent milker, really excellent—”

“Thirty dollars,” barked a large man.

“Thirty-five!” barked someone else.

“Forty!”

“Forty-five!”

And so it went. The proud creature was sold at last for a hundred dollars.

All the cattle brought handsome sums, and then it was the pigs’ turn. One by one they were displayed: the gilts, the shoats, the cranky old sow and her litter of half-grown piglets. When the mean brown boar was brought out the Delacey brothers suddenly opened their shaggy mouths and growled in unison: “Ten dollars!”

Every time a bid was called the Delaceys instantly raised it with such fierce bear voices that they soon discouraged competition. The boar was theirs.

“The three of them should be very happy together,” murmured Willy Sloper to Mr. Cutmold.

After the pigs were disposed of, Willy disappeared in the stable, a sudden heavy trampling was heard, and he came out leading the team.

These were good horses, though hard-worked. They stood there in the sunshine, quiet, broad-shouldered and strong. There was great patience and honesty about them. One could not look at them without a feeling of liking. Mark’s throat felt hot when he saw them; he had known these horses for a long time. His fingers knew well the feeling of their coarse manes. He had fed them apples, harnessed them a thousand times, clambered onto their broad backs and ridden the pastures and woods for miles around, leaned his head against their sides and listened to the huge, tranquil rhythms of their hearts. He did not like to let them go.

“Now this team,” cried Mr. Cutmold, a little hoarse by now. “This is a splendid team. A splendid team. Fine workers, strong, in prime condition. A mite thin, maybe, but that’s soon remedied. Six years old, and come of good mixed stock. What am I bid?”

“One hundred dollars,” stated a deep, melodious voice. Everyone turned. There on the fringes of the crowd stood a vastly fat man with a white round face like a Stilton cheese.

“That’s Waldemar Crown,” Rush whispered to Father. “He’s the one that wrote the letter, the one who wanted Mark.”

The faces that were turned toward the newcomer were staring and unfriendly. Even Mr. Cutmold’s overworked jaw dropped open. He stood dumbfounded, with his gavel raised in mid-air before he caught himself up and went on …

“Ah, yes; ah, yes. This gentleman has bid one hundred dollars, do I hear one hundred and ten?”

“One hundred and ten,” said a clear firm voice.

“Jeepers, it’s Father!” hissed Randy.

“One twenty,” said Waldemar Crown.

“One twenty-five,” said Father.

The duel continued. Heads turned hypnotized from right to left: first to Father and then to Mr. Crown. Cuffy twisted her bead necklace so hard that she broke it and never even noticed. Randy thought this must be one of those times you read about, when you could hear a pin drop.

“Father looks mad,” whispered Mona, in awe. “I never saw him look like that before.”

Father stared straight ahead at Mr. Cutmold. There were unaccustomed spots of color on his cheeks, and his eyebrows were severely drawn together. Every time Waldemar Crown made a bid, he topped it.

“One-seventy,” said Mr. Crown.

“One-eighty,” retorted Father.

“Two hundred,” snapped the fat man.

Father took a deep breath. A little vein stood out on his forehead.

“Two hundred and fifty!” he said.

Waldemar Crown hesitated and was lost. Mr. Cutmold leaped into the silence with alacrity.

“Two hundred and fifty do I hear two-fifty-five going going gone SOLD to the gentleman on my left: Mr. Martin Melendy of the Four-Story Mistake!”

People actually applauded, even the Delacey brothers. Mr. Crown slapped his broad-brimmed hat on his head and walked away, fat and furious.

“But gee, Mr. Melendy,” Mark was protesting, “you shouldn’t have done it! I told you you could have the team, just for a present, I mean. Gee, all that money, Mr. Melendy. I don’t want to take it. Why did you ever do it?”

“Stop talking nonsense, Mark. I wanted to do it. Why, I couldn’t let those good horses go to a blackhearted rapscallion like Crown, could I? I’ve heard tales of how he treats his animals. I’m glad to have that team.”

“Father, you were wonderful!” Mona said. “You looked just like Humphrey Bogart.”

“He made me think of Sydney Carton,” Randy said.

After the drama of the horses, the chicken sale was tame. The Melendys didn’t even wait to see what became of the New Hampshire Reds (Rush said it sounded more like a football team than hens). But there were those among the crowd who had been living for this moment. The bidding was sharp and high.

The children vanished into the house to prepare for the show. The crowd thinned a little. Willy and Mr. Cutmold helped old Harrison Neeper load cows onto his truck, and crates of hens were placed clucking and complaining in ramshackle jalopies covered with back-roads dust.

“Now we’ve got a team, what are we going to do with it, Willy?” said Father.

“Say, Mr. Melendy, it sure raises up a lot of consequences. Can’t let a team lay idle, you know. First thing, we’ll have to start a real farm to work ’em on.”

“Grain,” said Father gloomily. “Oats and all that sort of thing. Plowed fields in the spring. That means a plow. Maybe I can borrow one. Then the mowing and shocking. That means a reaper or a combine. Then the threshing. That means— Oh, Lord,” sighed Mr. Melendy, “what have I done?”

“Don’t you worry, Mr. Melendy. I’ll figure out a way to use ’em. And they’ll make real nice company for Lorna Doone.”

“Names,” said Father. “Have they got names?”

“Jess and Damon. Damon is the one with the star on his forehead.”

And now it was time for the show!

In the end they had decided to have it behind the house because the earth was more or less flat there, and the high clothesline was the logical place to hang the curtain. Benches and boxes were arranged to accommodate the audience, and the shed roof, cellar doors, and kitchen steps all made excellent vantage points.

Rush opened the show by dashing dramatically into the old Brahms Rhapsody. The piano had been moved outdoors, which didn’t agree with it. It twanged like a cheap tin music box, but Rush did the best he could, and everybody was impressed. Next he played the Schumann Novelette he had been slaving over all summer.

After that Randy danced while he played. Yes, in her pink costume, and new pink ballet slippers, with a splendid disregard for grass stain, Randy danced like a fairy; floated above the mole hills and ambushed clothespins which would have tripped anyone less skillful. This was such a success that she had to improvise an encore.

After this Jerome Hubbard played “God Bless America,” and “O Sole Mio” on his musical saw. Dave Addison recited the Gettysburg Address. Little Nancy Skeynes did her famous tapdance on an overturned washtub; Mark obliged by walking on his hands and turning handsprings, and then Mona, with the wrinkles scrubbed off her face, did a monologue which she had written herself. It was all about a captive French girl sending code messages to the British from an abandoned lighthouse, and was really by far the most successful thing about the show.

At the end everybody stood up and sang “The Star-Spangled Banner,” with Rush playing a loud impassioned accompaniment, and the Fair was over.

“If only Mrs. Oliphant could have seen it,” sighed Mona, “then it would really have been perfect.”

Later, after the Red Cross money and Mark’s livestock money had been counted (and fine substantial sums they were, too), the weary time of cleaning up arrived.

In the fading light the children moved about, taking down the Chinese decorations to be packed away for some future festival. Papers were littered all over the lawn. Mark was gathering them up in armfuls and stuffing them into a burlap sack, to be kept for the paper salvage. Rush took the Bedouin tents apart. In one of them he discovered Oliver, cross-legged on the ground, drinking leftover punch right out of the bucket.

“Oh, brother, are you going to be sick tonight!” said Rush with a sort of awe; a prophecy which subsequently proved correct.

Staggering with weariness they managed to clear away the worst of the mess, though plenty was left for tomorrow. Everybody helped: Cuffy, Willy, Father, everyone. Isaac and John Doe, let out of the house at last, hurled themselves about the lawn, leaping upon everyone and speaking with loud, expostulatory barks.

A plaintive mooing was heard in the distance. Rush looked wanly at Mark.

“Jeepers. The cows. We forgot to milk them!”

As they trudged toward the pasture Mark stooped and picked something out of the grass. It was one of Oliver’s handmade tickets. Mark looked at it in the faint light, and smiled a little.

“‘Admit one,’” he said aloud. “That’s me, all right. I’ve been admitted. To a family. To a swell, real family. Boy, am I ever a lucky guy! No guy I ever heard of before was ever half so lucky!”

“Don’t be a dope!” said Rush. “Who’s lucky? Ran, and Mona, and Oliver, and I. We’re the lucky ones. Didn’t you know that?”