“Fish and caterpillars. Caterpillars and fish. They’re the things that Oliver lives for,” said Rush wearily, one Saturday at lunch. “This is the third time we’ve eaten chub this week, and all because Oliver’s learned how to fish.”

“Free and unrationed,” said Cuffy severely. “And nourishing.”

“Be glad it’s the fish we have to eat and not the caterpillars,” suggested Mona.

Oliver looked up dreamily. “You can eat caterpillars, you know. African savages do; I read about it in a book. Big white grubs they eat. I wonder if—”

“Well, you can just stop wondering, my friend,” Father interrupted. “We’re not savages, at least not authorized ones; we’re the softened products of civilization, thank heaven, and our diet doesn’t include the larvae of Lepidopterae. At least not yet. Probably the day will come when they’ll be found a most valuable source of vitamin Q, and we’ll eat them every day as a matter of course along with our green, leafy vegetables.”

“Ugh,” said Mona, shuddering fastidiously but going right on eating.

“Chub!” said Rush, taking a bone out of his mouth. He made the word sound like a swear. “Chub, chub, chub, chub, chub! All summer long nothing but chub. Baked, grilled, fried in meal. Oliver, couldn’t you please, just once, catch a trout, or even an eel?”

But Oliver wasn’t listening. He was thinking about something else. There was mashed potato on his chin, and a dash of jelly on his cheek, but his eyes looked into a distance of their own and saw something which made them shine with a grave contentment.

It was true that during the past month he had been making an exhaustive study of the two subjects, caterpillars and fish. They were the twin enthusiasms of his scientific nature. Just now the insects were a little in the lead.

Oliver wondered how he had lived so long without paying any real attention to caterpillars. It seemed a terrible oversight. Perhaps it was because he had never before lived in a place where caterpillars were so abundant. Here, in the gardens and woods, they were everywhere. Small and green, they swung themselves down from the trees on threads, and got caught in your hair, or were discovered hours later inching themselves along your collar. “Measuring you for a new suit of clothes,” Willy said. And then, of course, there were the tent caterpillars in their ugly pavilions of soiled gossamer; and the furry kind, red or black, such as there are everywhere, always ruffling busily along the roads, or up and down stalks. Oliver, like any other child, had patted the furry ones, stepped on the tent ones, and felt a cold flicker of repulsion when he picked one of the thread-swingers off his collar. Otherwise they had never occupied his thoughts.

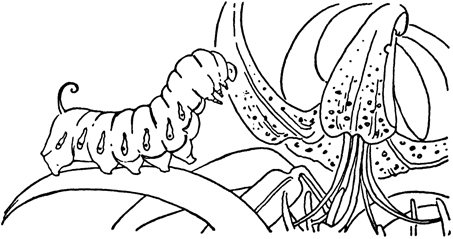

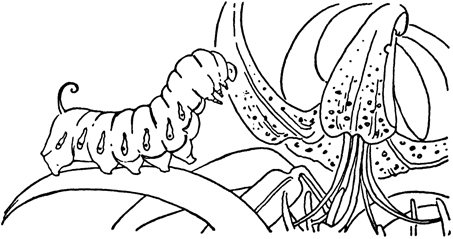

All this was changed, however, one morning in mid-July. One day, impersonating a Sherman tank, he was bellowing and threshing his way among some of the shrubs near the summer house, when he came face to face with an extraordinary thing. It was something which looked like a tiny, elaborate trolley car. It was perched on a leaf, standing firmly on ten blunt little round feet that could have been wheels; and, exactly like the connecting rod on a surface car, a sort of horn or antenna stuck up at one end of it (Oliver decided the hind end, the thing was probably a tail). The other end was raised defiantly, and Oliver thought he discerned a sort of face there. The whole creature was a rich cinnamon brown color, and along each of its velvety sides was arranged an ornamental row of creamy scrolls.

“Gee,” breathed Oliver, and stuck his finger out in front of the fantastic thing. “I never saw one as big as this, or as fancy! Come here and let me look at you.”

At that the caterpillar rippled forward, exactly as if it had understood each word, raised itself up again and placed its two front—what would you call them—paws? Feet? Hands?—right on Oliver’s grass-stained finger. Oliver held his breath. He had never been so flattered in his life.

That was the beginning of his new passion. After that came a long period of collecting. Caterpillars of every type were brought home by Oliver to be housed in Mason jars, jelly jars, milk bottles, and any other transparent receptacle that could be appropriated without too much hue and cry. (Cuffy had thought of several things to say when she discovered the cabbage caterpillars in her best glass baking dish). There was a different specimen in every jar, along with a generous supply of whatever they had been eating when Oliver had found them.

Cuffy and Mona protested strenuously, but Rush and Randy were eager collaborators, and even Father said, “It’s a good interest for a boy. He can learn a lot about human progress by watching caterpillars.”

Unwillingly resigned, Cuffy cut out rounds of mosquito netting to put over the jars, and Mona tied them on with different colored bits of worsted.

“There,” she said to each one, as she pulled the fastening tight. “Stay in there, now, till you turn into something less revolting: a butterfly or moth.”

Nevertheless, somehow or other, in their sly, insinuating way, the creatures often managed to escape, and from time to time there were shrieks from some member of the family.

“Cuffy! There’s a caterpillar in my hat!” Or, “Oliver! One of your rotten old worms is building a cocoon in my hairbrush. Come and take him aw-a-a-y!”

At times like these Oliver preferred to leave the house quietly and rapidly till the storm had blown over. After a while the rest of the family learned to bear their cross with patience and finally even with a sort of enthusiasm. It happened occasionally that Oliver forgot to feed his pets. It was hard to keep up with them. Heavens, how they ate! Leaves, stems, everything they could get their industrious jaws on. It was as if a growing boy in one day ate nine Thanksgiving dinners. Oliver had to fill the jars first thing in the morning and last thing at night, and the night feeding was the one he liked to forget. This meant that often his pets would be found striding ravenously about in their glass prisons, or trying to push off the mosquito netting in order to widen their frantic search for food.

“Oh, for Pete’s sake!” Rush would groan. “The parsley caterpillar’s finished the parsley again. He’s gobbled up a bale already. I suppose I’ll have to get it some more.”

Or Mona would push open the kitchen door. “Cuffy, have you got a cabbage leaf? The disgusting cabbage caterpillars are all out of their disgusting cabbage.”

Even Father, upon occasion, was to be seen flickering gloomily about the garden with a flashlight to get “more lilac leaves for the confounded cecropia larva.” After all, he had encouraged this hobby.

When the caterpillars had eaten several hundred times their own weight in greenstuff they began making cocoons. In each glass jar Oliver had put some earth or a strong twig, depending on whether the creature in question was a burrower or a weaver. Even Cuffy and Mona found themselves interested in the progress of the cocoons: they were so ingenious, beautifully knitted, and in some cases lovely to look at. The monarch caterpillar, for instance, contrived a waxy chrysalis of pale green, flecked with tiny arabesques of gilt. It hung from the twig on a little black silk thread, like the jade earring of a Manchu princess.

“How lovely!” cried Mona. “Oh, if there were only some way of preserving them. I’d like to have a pale-green dress all buttoned down the front with those.”

Oliver was outraged, and Rush said, “There’s a woman for you. Always thinking of the beauties of nature in terms of wearing apparel. Can’t see a shiny spider web without wanting to make a snood out of it. Can’t see the Grand Canyon without wanting to dye something to match it. Can’t—”

“Oh, Rush, if you could hear how stuffy you sound!” cried Mona. “Pompous and stuffy and about fifty years old. I suppose you’d rather have me quote a poem!”

“Well, you never lost an opportunity yet,” Rush observed. “What’s the matter, didn’t Shakespeare ever write any poetry about cocoons?”

The nice thing about the monarch chrysalis was that the creature which emerged at the end of two weeks was as beautiful as his case. Orange-red and cream and black, like the petals of a tiger lily, he clung to the twig till his wings dried and widened, and then Oliver took him to the open window and deposited him gently on a leaf. Watching the butterfly fluttering away in the sunshine Oliver could not help feeling a little like God releasing a new soul into the world.

Cocoons kept turning up in the queerest places. A few caterpillars had inevitably escaped and Cuffy was loud in her protests at finding two little silk hammocks clinging to the living-room baseboard, another stuck to Father’s typewriter, and another jade earring dangling from the dining-room ceiling.

“Gives you the creeps,” she grumbled, “to imagine them things prowling around the house like they owned it, and building their nests any old place.”

“Cocoons or chrysalises, not nests,” said Oliver firmly, and was grateful that though she grumbled Cuffy did not destroy the cocoons.

Oliver was having a wonderful summer. He loved it all. Fish, insects, swimming pool, woods, his own bicycle. What more could a boy ask?

Yet Oliver did have something more. He had a secret world that he entered when he went to bed. A world of which his family had no idea, Cuffy least of all. And it was by no means the world of dreams.

On the nights when he was not immediately claimed by sleep, and when he was reasonably sure of not being discovered, Oliver would sit up in his bed, turn on his flashlight and point it at the window. The effect was instantaneous and rewarding.

Out of the thick, night woods in the valley the moths came, flying in hundreds, fascinated by the shining eye of Oliver’s window. As if attached to threads they were drawn by the light; clouds of them, swarms of them, fluttering out of the dark. And with them came all kinds of beetles; as well as the midges and mosquitoes which were small enough to crawl through the screen’s meshes. Oliver didn’t care, though. He slapped and scratched absently, and stared at the moths. He never tired of watching them, they were so beautifully made, with their patterned wings, tiny fur jackets, and dark, blank eyes. Up and down, up and down the screen they walked on tiny legs, their wings trembling. Others thumped and knocked against the broad overhanging eaves, and still others kept emerging from the shadows, soaring and drifting, like lazy confetti or blown petals in the dark. And now in Oliver’s room a sound could be heard: a whispering, a rustling, of hundreds of small, soft wings.

Oliver sat transfixed and spoke quietly from time to time, telling himself the names of the ones he knew. “There’s a Virgin Tiger moth,” he’d say confidingly. “There’s a nice Sphynx, very nice,” or “Oh, boy, what a swell Leopard.” When an interesting one came along that he didn’t know, it was necessary for him to get out of bed, find the moth book and look it up. Really, with all this nocturnal scientific research, Oliver got very little sleep.

Sometimes a big hawk moth would appear, clinging to the screen. His eyes were little, fierce flecks of fire, and his fringed antennae were like tiny ferns or feathers. His wings vibrated so rapidly that they became a humming mist. There he would cling, in love with the light, staring at it, longing to reach it. Why? Oliver wondered. What did the light mean to them all?

Sometimes a big beetle would come, blasting and intoning, repeatedly hurling himself so hard against the screen that often he fell over on his back on the windowsill, and lay there for twenty minutes at a time, grappling the air with frantic, spurred legs. He never learned.

“Nitwit,” Oliver would say to him contemptuously. “Thundering around that way isn’t going to get you anyplace.”

Danger also lurked beyond the window. Suddenly, darting up from nowhere, savage and swift, would come a bat. For a split second Oliver could see its tiny snout and mouse’s ears, as it pursued the larger moths. His heart never failed to give a little skip when he saw it, for now, to him, the scene framed by his window had enlarged, become enormous. The moths had changed from moths into animals, or people, or fantastic beings from another world; and the bat was no longer a bat, it was instead the devil himself, or an ogre among gauzy innocents, or a black panther in a jungle. Oliver, watching, had become moth-sized, too, and felt a thrill of absolute terror when the bat appeared. It was exciting, and he shivered as he looked. The flashlight dramatically illuminated all these activities beyond the window.

One night after he had turned off the flashlight and lain down to sleep, and had just begun working on a dream, he was aware of a sound. At first he heard it reluctantly; far away, a gentle interruption which persisted. At last he opened his eyes and concentrated on listening. It was a velvety sound, very soft, like the pat, pat, pat, of a little felt slipper on the eaves. “A moth and a pretty good-sized one, too,” said Oliver, sitting up fast, interested as any hunter stalking his prey. He pointed the flashlight at the window and turned it on. Instantly the small insects which had been asleep on the screen woke up and began their tireless promenading up and down, always up and down, in their ceaseless search for an entrance. Pat, pat, pat, just out of sight the mysterious one bumped gently against the eaves. Oliver held the light temptingly close to the screen, willing the stranger to appear. And presently he was rewarded.

Floating out of the dark, knocking against the overhang, came something so beautiful, so fairylike that Oliver hardly dared to breathe. The thing was a moth, but like no other moth that he had seen. Its wings were as wide as his two hands opened out, as frail as a pair of petals, and colored a pale, pale green: a moonlit silvery green.

“Gee,” whispered Oliver. He sat there staring. “A luna! I never thought I’d see a real luna!”

It came close, hovered against the screen, and paused there. He could see the long curved tails on its wings, the delicate white fur on its body and legs. Oliver thought he had never seen anything so perfect. He and the moth watched each other for a long moment; neither moved.

Then suddenly, sharp, quick, dark against darkness, up came the bat. Oliver jumped to his feet, clapping his hands, and shouting.

“Get out of here, bat! You get away, you get away!”

With a sound like the flutter of a candle flame the bat departed. But Oliver knew it would be back again. With his finger he tapped gently against the screen where the moth was clinging.

“Go away now, luna,” he said to it. “Go away fast, go home to the jungle where the panther won’t get you.”

The moth fluttered away from the screen, reluctant and bewildered. Oliver put out the light so that it would go back where it belonged: back to the mysterious, leafy place from which it had come.

Pat, pat, pat went the little felt slipper under the eaves. Pat, pat, pat, and then silence. Oliver looked out. He could just see the great, pale creature floating toward the woods, drifting away on the tides of darkness like a flower on a pool.

There was a sudden sound. Light came into the room; Oliver turned guiltily.

“Oliver Melendy!” Cuffy’s voice sounded queer without her teeth. “What are you doing? Was that you a minute ago, clappin’ and hollerin’?”

“It was me,” admitted Oliver, climbing back into bed and pulling the sheet up over himself and the hundred-odd little midges that had crept in through the meshes of the screen. “I was just scaring away a black panther.”

“Black panther!” scoffed Cuffy. “It’s all them doughnuts you ate. Milk of mag for you tomorrow, young man.”

Even the thought of Milk of Magnesia failed to diminish the triumphant joy of the last few minutes. Instead of the usual groans of protest which met such an announcement, Oliver turned upon Cuffy a smile of radiant good will. “Okay, thanks. Good night,” said he, and Cuffy left the room with a puzzled look.

For a long time after that whenever he thought about the luna moth he felt happy. He was careful not to think of it too often. Just once in a while he would look into his own mind and let himself see it again: his discovery, his beautiful guest, his secret. Seeming more than a moth, it paused there at his window: rarest green, fragile, perfect, living. The thought of it made Oliver happy all over again.

This is what he was remembering that day at lunch, with the mashed potato on his chin, the dash of jelly on his cheek, and the wondering contentment in his eyes.