What do I really want? With so many options, it was difficult to know. I sought solace and direction in the Bible. I picked up where I left off; Matthew 5:10.

“Blessed are they which are persecuted for righteousness’ sake: for theirs is the kingdom of heaven.”

It was after midnight, so I wrote:

Friday, March 28, 1890

“Yesterday I spent time with the Witherspoons. Thank you for sending them to rescue me, Lord. They have given me so much. I am confused about my mission. Help me to make the right decision; the one that’s best for me.”

I slept.

Clara came into the bedroom and woke me around eight o’clock in the morning with another attractive dress and apron to wear, as well as the medicine box. “Mr. Witherspoon is in the shop with Jonathan finishing up the order that’s due Monday.” She hung the dress on the hook behind the door. “He said to send you out around eleven o’clock. That gives you time to get cleaned up and ready for the day, have breakfast, and write your postcards. The postman usually comes around two o’clock.”

“Thank you, Mrs. Witherspoon,” I said, sitting up and wiping my eyes on my shirtsleeve.

She came over to the bed and sat down beside me. “Let’s see how your forehead is healing.”

The air felt cool to the wound when the bandage was removed. Clara used a soft, soapy cloth and dabbed it on the cut to disinfect it once more. “I would say you could go without it now, but because you’ll be in the shop today, we’d better go one more day with a bandage.”

“Good idea.” I sat still, watching her as she gently attended to my wound. “What can you tell me about Jonathan?”

“Oh, he’s a young man, maybe three years older than you. He wants to get into the woodworking business, so Samuel is teaching him. He’s gained quite a lot of skill over the past year and shows great promise. He keeps to his schedule and has been a real help as our business has grown. He earns a fair wage too.

“That is a very pretty dress. Blue is my favorite color. Is it one of yours?”

“Yes. I thought this one would compliment your eyes. There. You’re all set. I’ll see you later at the table.” Clara packed her box and closed the door behind her.

I sighed. Clara and Ma had a lot in common. After washing and brushing my teeth, I slipped on the sky blue dress with tiny white dots all over it. A bright, white scarf was with it to tie my hair back. Over it, I put on the white apron and tied it behind me.

At the table, Clara said, “Oh, Emeline, that blue dress does become you.” Breakfast was simple: apple quarters, sliced cheddar cheese, scrambled eggs, and a small glass of milk.

“Thank you.” I noticed she had already put the inkwell and quill with my postcards on the table. “So much has happened. I couldn’t fit everything on one little postcard.” I turned the first one over.

Clara laughed. “True. Short and sweet, as they say.”

“Hmm. I’ll address them first. Mr. Pickwick will deliver

Mr. Thompson’s.”

Miss Ambrose, c/o The Schoolhouse, Kearney, MO

Mr. Thompson, c/o The Mercantile, Kearney, MO

Mr. Pickwick, c/o The Mercantile, Kearney, MO

Mr. & Mrs. Cooper, 25 E. Washington St., Kearney, MO

Harriet Hudson, 26 E. Washington St., Kearney, MO

I wrote on each, in my best and smallest handwriting, that after a tumultuous trip, I had arrived safely in Indianapolis. I would continue on to Boston by train. I had decided that Dakota would stay with new friends in Indianapolis until I could send for him. I added a personal line for each person and then I signed, “I miss you, Emeline.”

There it was: my decision. I was being true, not only to Pa, but to myself. I really want to meet my grandfather and be with true family again. Not just for Pa, but for myself. And, I can always do something else after I’ve met Grandfather Silas if I want to. “Now then. They’re ready to go.” I gathered them together.

“That’s fine,” Mrs. Witherspoon said with a grin. “It’s nearly eleven. Go ahead and put them in the postbox by the road and go on over to the woodworking shop; I’ll drop in later. I need to catch up on my mending.”

As I crunched across the gravel path, I could hear noises coming from the workshop: a regular click, an intermittent whir, and a rhythmic swoosh. The door was propped open. I entered and found Samuel standing at the wood lathe, pumping the treadle underneath, and skillfully carving a piece of maple into an ornate spindle. A handsome young man worked at the bench on another piece of wider maple. He was carving hills and valleys into its flat face with a special plane to create a decorative molding. I stood near Samuel and watched him work. “That looks like loads of fun, but difficult.”

He laughed. “Just about finished with this one.” He picked up some wood shavings and held them onto the piece as it turned, rubbing it from one end to the other. “See how a pile of shavings takes off all the little scratches and burs? It almost shines now.” He took the spindle off the machine and handed it to me.

“It’s so smooth. Someday, I’d like to try.”

“First, we’ll start you on sharpening our chisels. As you work, you can practice with them on scrap pieces of wood. Your chance on the wood lathe will come if there’s enough time before you leave.” He turned toward the workbench. “Jon, here’s someone I’d like you to meet.”

The young man stopped and turned toward me, wiping his hands on his canvas apron. His dark brown hair curled loosely over his forehead and contrasted with his blue eyes. His smile was dazzling. “How do you do,” he said. “My name is Jonathan.”

I stammered, “Um. Hello. My name is Emeline.” My cheeks

grew hot.

“Samuel told me about you. How long do you think you’ll stay?”

“Just until I earn enough to buy a train ticket to Boston. I’m not sure yet.”

“Well, it’s nice to meet you. I’d better get back to work now. Perhaps we can visit later.” He winked at me and looked at Samuel.

“Thank you,” I said, my voice lilting up as if it were a question.

“Come over here and I’ll show you how to sharpen tools, Emeline,” Samuel said with a grin.

Grateful for the task, I gave him my full attention. I was standing in front of a table with a vise and a board with three flat black stones. “What are these?”

“These are sharpening stones. Let me show you.” He was holding a flat chisel, which was about one-half inch wide. “See this bevel? That’s what we’re going to sharpen. It’s important that you hold it exactly at the angle of the bevel. We don’t want to lose that. We just need the edge sharpened. To succeed at this kind of woodcraft, you need patience, practice, hardwoods like maple, oak, cherry, or walnut, and good, sharp hand tools. If you sat down at the lathe with a piece of pine and a chisel, it would gum up with the sap from the soft wood and be rough-looking. Even with a piece of good hardwood, if your chisels are dull, your cuts will be rough and not precise. So, this is a very important job.”

“I see. I’ll do my best.”

He put a little water on each of the three stones. “Now. You hold the chisel so the bevel is flat against the first stone, the coarse grit, and rub it away from you and then back to you. Not side-to-side. Do that about thirty times. Then move to the next stone, which is a medium grit, and repeat. Finally, do the same on the last stone, the finest grit. Let me show you.”

He put a piece of scrap wood into the vice and used an unsharpened chisel on it. “Hold it against the wood like this and push to the left.” A shaving came off. “See how rough the wood is after this cut?” Then he went through the sharpening procedure and cut the wood again. “Now, feel this cut.”

“It’s smooth!”

“Right. A sharp tool makes all the difference. Now, you try it.”

I took another dull chisel and scraped the wood. “It seems sharp to me. It cut the wood, but I see it isn’t smooth.”

“Uh-huh,” he said, hands in his pockets.

It took awhile, but I sharpened this chisel on all three stones, and then cut again. “Oh, that was much easier and smoother.”

“Right, then. You’ve got it. I’ll leave you to it and go back to the lathe. Just ask if you have any questions, and be careful. I don’t want you to cut yourself!”

“I will.”

About three hours later, I was finished with the sharpening task. “I’m finished, Mr. Witherspoon,” I said. “May I do anything else?”

“There’s a broom and dustpan next to the barrel of shavings in the corner. You can sweep up for us.”

“Alright.” I grabbed the broom and swept the whole shop, excusing myself when I got close to Jonathan and Samuel. They both politely moved away so I could sweep, and returned.

“That’s good,” said Samuel. “I think we’re finished for the day. “I hear Mrs. Witherspoon coming.”

Clara came into the shop with a basket of eggs over her arm. “Look what the hens gave us today: eight lovely brown eggs. How did you like working in the wood shop today, Emeline?”

“It’s wonderful! I learned to sharpen chisels today. I’m so impressed with the beauty of this work.”

“We have been receiving lots of new orders. More and more people are moving here and building houses, and they love to put this fancy woodwork in them.” Turning to Samuel and Jonathan, she asked. “How did it go today?”

“Very well. We are on schedule to deliver the balusters and molding Monday afternoon,” Samuel said.

“See this?” With a broad smile, Jonathan showed Clara a piece of the molding he’d finished. “I love the smoothness of all the peaks and valleys.”

Clara ran her hand over the work. “That is excellent workmanship, Jonathan. You should be proud.”

“Thank you. Well, shall I see you all Monday morning, bright and early, about 7:00?” Jonathan asked.

“Sounds good. See you then. Have a nice weekend, Jon,” said Samuel.

“Goodbye!” He saw me smile and wave before he turned to walk away.

Oh, my heart.

Samuel locked the doors after we left the shop and headed toward the house. Inside, we sat in the parlor for awhile, talking about the day and the plans for the next. For the Witherspoons, Saturday was set aside as a day for doing laundry and working around the house.

Specifically, tomorrow was a day for planting the vegetable garden and I was invited. Samuel and Applejack would plow the furrows, while Clara and I planted and covered seeds of bush string beans, carrots, radishes, peas, and broccoli. Inside the house, she had a box of dirt for seeding tomatoes. Because nights could still be cold, the tomato seedlings would be transplanted later to the garden.

“May I ride Dakota for awhile after the garden is planted? I miss riding him.” It had been days since we arrived.

“Surely,” Samuel said. “In fact, I forgot to tell you. I’ve let him into our fenced pasture for the last two days. He’s been enjoying the grass, romping around with Applejack, and having a grand time.

And, so, life went on with the Witherspoons for about a month. I had written more postcards home, continued my Bible reading and prayers, watched the garden grow, and had learned more about woodworking, and Jonathan.

I’ve got to admit that Jonathan was not making it easier for me to leave. He was always kind and friendly, but not too much. I mean, we were just friends. After all, I am only thirteen years old. Too young for anything more than that. But, during work, we talked about things we liked or didn’t like. Things that were important to us. We shared memories of special times and people. He joked with me because, he said, he liked my laugh.

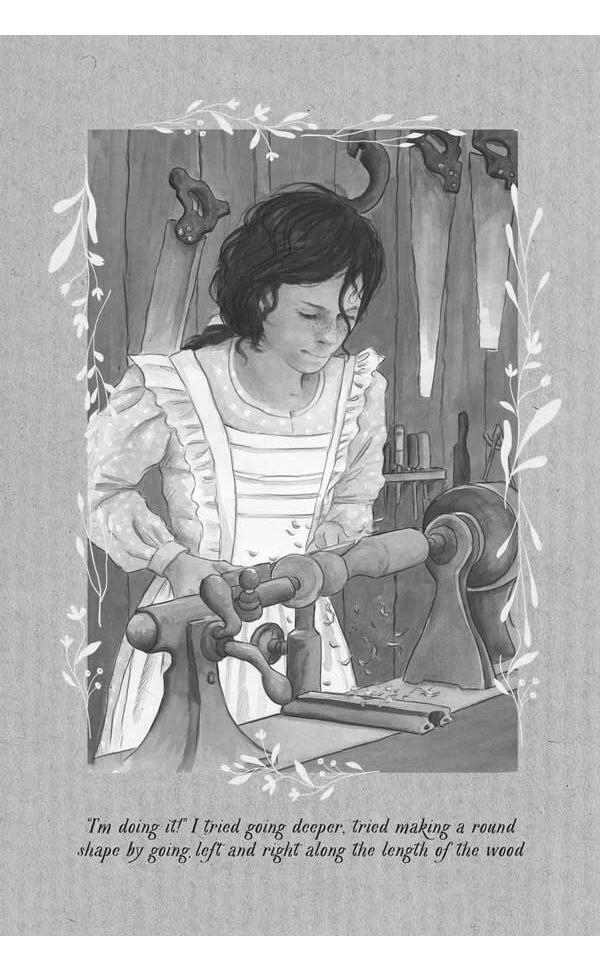

Samuel let him teach me how to use the plane and make molding trim. I even sharpened the blade for the plane. At last, Samuel said it was time for me to try my hand at the wood lathe. I had watched him often and had learned a lot just by watching.

“You’ve watched. Now, you’ll do. It’s a skill that takes a lot of practice - especially if you have to do things exactly the same way multiple times. Don’t expect this first piece to be anything at all. I want you to just play with the tools this time. Get a feel for how they work. Don’t worry about style, measurements, or anything. Try different kinds of chisels as you go.”

“Great!” I got into position in front of the lathe, which was bolted to the floor. The belt was on the largest top wheel, which meant the slowest speed. “Is this the correct wheel?”

“For now, yes. Now, hold the chisel with both hands, as you’ve seen me do. Move the block to steady your hands when you need to. Use whichever foot you want on the treadle and start it up.” The now familiar whirring started. “Just touch the wood with the corner of your chisel and ease it into the wood.” The wood shavings came off with sort of a vibrating sound.

“I’m doing it!” I tried going deeper, tried making a round shape by going right and left along the length of the wood. I turned the chisel the other direction, holding my hands the opposite way and tried to make a convex curve. It was amazing how differently each chisel carved the wood. Some chisels were flat, some were curved, and another had a deep “V” shape. “This is so much fun!”

Samuel laughed, “Yes, I enjoy it too, very much. It never gets old for me. Each piece is unique - even if it ends up looking exactly like another - because each piece of wood is unique.” He changed out the wood for a new piece of maple for me. “You just keep changing these and practice. Make sure you get it locked in tight.” He pulled at the lever. “Once you think you have it tight, make it turn for a moment, then stop, and tighten it again. Tomorrow, I’ll show you how I made this spindle.” He set one down near the machine.

I discovered I loved woodworking. For the next two weeks, I made spindles. The first were of marginal quality, at best. But each day I showed improvement until they were nearly as good as Samuel’s. He just had to spend a minute or two to perfect them.

One evening after supper, I announced, “It’s taken longer than I anticipated, but I have enough money now to continue my journey.”

Clara set down her embroidery in her lap. Samuel closed his book and put his fingertips together, his elbows on the arms of the chair. Clara said, “We knew this day would come.” She wiped the corner of her eye with the cuff of her sleeve.

“We all have grown very attached to you, Emeline,” Samuel said. “I know you’ll keep in touch and let us know how you’re doing.” He leaned forward, elbows on his knees, his chin resting on his hands, fingers locked together. “If you ever want to come back and stay with us, we’d welcome you with open arms. Consider us family, Emeline.”

“Oh, my!” I wasn’t expecting this to be so hard. “I would be honored.”

Samuel relaxed back into his chair and rocked. “We’ll miss you.”

“I will miss you too. I would love to stay right now, but I really want to get to know my grandfather before it’s too late. I hope you can understand that.”

“We do. When do you want to leave?” Clara pulled the train schedule out of a book in the bookcase. “It looks like there’s a train leaving at 8:00 in the morning on Friday. That gives you a day to get ready. And you’ll want to say good-bye to Jonathan and Dakota.”

“Friday is perfect. And it’s early enough that my departure won’t interfere with the day’s work here.” I said. “Do I need to purchase the ticket early?”

“Yes. We should go to the train station tomorrow,” Clara replied.

That night in bed, I opened the Bible to Matthew 5 again. I had been reading the book of John during my stay, but now I wanted to return to the Beatitudes. I read Matthew 5:11 and 12.

11 “Blessed are ye, when men shall revile you, and persecute you, and shall say all manner of evil against you falsely, for my sake.”

12 “Rejoice and be exceeding glad for great is your reward in heaven: for so persecuted they the prophets which were before you.”

I wrote:

Wednesday, May 7, 1890

“Dear Father in heaven, thank you for your protection and provision on this journey. I ask You for safe travel and that my search for my grandfather be a quick one. Bless my grandfather and friends, both old and new. Amen.”

Thursday morning, after breakfast, Clara and I took the buggy to the station. The now familiar building with its arched windows and doors held a new excitement for me. “I’ve never ridden a train before.”

“I have, a long time ago. When I rode it there was just one passenger car and one ticket price. Now they have the plain, medium, and fancy cars,” she said.

“Plain is fine for me.” We approached the ticket master’s counter. “I’d like to purchase a one-way, third-class ticket to Boston, please, for the eight o’clock train on Friday.”

“Very well. That will be $30, miss,” he said. He looked very official in his suit with braided trim and conductor hat. His handlebar mustache was thick and waxed so that it turned up at the ends.

I pulled out cash I had packed in my pocket and gave it to him. “Here you are.”

He began counting all the dollars and coins, of which there were considerable. “Just checking. Yes, it’s all there. Thank you, miss. Here is your ticket. Don’t lose it, now! We’ll see you Friday morning. Be here about a half hour before departure.”

“Pardon me,” Mrs. Witherspoon said. “Would there be a railroad employee, maybe a conductor, whom I could speak with on Friday morning?”

“Yes, ma’am. There will be three conductors, one for each car. You can speak to the third class conductor who will be helping people board.”

“Thank you, sir,” she said. We turned around and headed back for the buggy.

“Ah well, that’s done,” I said.

Mrs. Witherspoon gave me a weak smile, but her eyes flickered on and off my face. “Tch, Tch,” she said to Applejack.The rest of that day was awkwardly silent. First, I washed all my soiled clothing and hung it out to dry. Clara was kind enough to give me the two dresses I had been wearing. “You’ll need more than one dress in Boston,” she said. That makes three dresses, plus my two riding outfits, coat, hat, and boots that I own. I made a list of things to pack in my rucksack for the trip. I wouldn’t need everything I came with at first. I would wear my money belt with most of my money in it, and I pinned the pocket watch inside my dress pocket. Since the train stopped for twenty minutes to refill, I would need to know the time!

In my rucksack:

- (3) dresses (folded and rolled up)

- (1) riding outfit (folded and rolled up)

- Hairbrush, hair ties, toothbrush, tooth powder, soap, washcloth, and towel

- My new Bible

- Pa’s knife (in its sheath)

- One canteen full of water

- Some coins for food at the train stops and for the first night’s lodging

At the end of the afternoon, it was time for a teary good-bye to Jonathan and Dakota. Jonathan gave me a big bear hug and told me to write. Dakota had no idea why I was crying as my arms circled his neck. He snorted and pawed the ground.

That night, I packed my rucksack, maybe for the last time. I read Matthew 5:13.

“Ye are the salt of the earth: but if the salt have lost his savor, wherewith shall it be salted? It is thenceforth good for nothing, but to be cast out, and to be trodden under foot of men.”

I thought about that. What is it to be salt? Then I thought about the properties of salt: it preserves, it cleanses, it causes thirst.

I wrote:

Thursday, May 8, 1890

“Dear Lord, I think I understand. You want us to preserve your Word, to clean up evil in the world, and to draw other people to You. Help me to be salt in Boston, and even on this train ride. Thank you. Amen.”

“This is harder than I imagined,” I said to Clara Friday morning as I put on my rucksack after an early breakfast.

“It’s difficult for us too. We will miss you, Emeline.” Clara held my hands and kissed my cheek. “Godspeed.”

“Time to go,” Samuel said. We all walked to the buggy and Samuel helped Clara and me get in. Three on the buggy seat was snug, but doable. “Tch, Tch,” he clicked to Applejack.

At the station, we pulled into a space and tied Applejack to a rail. The three of us went into the station’s arched doorway and stared at the huge train that went right through the center of the room. Its engine was huffing outside as men filled it with water for the steam and wood for the fire. There were three cars, but all of them were third class this trip. I was directed to the first car behind the engine. The conductor was helping people up the stairs and into their seats, taking their tickets as he did so.

Clara sought the conductor and said, “Sir, would you do us a great favor and watch after this young lady on the trip. She is traveling alone. Just check on her now and then and make sure no harm comes to her, would you please?”

The gentleman smiled and nodded. “I’d be happy to. Don’t worry about the lass. I won’t let anything bad happen.”

“Thank you,” Clara said. She turned and hugged me tightly. Then she took my arms and looked directly into my eyes. “You be careful, Emeline, and be sure to write as soon as you can when you get there. We’ll be watching the postbox every day. Here’s a bag of food for your trip.” She handed me a paper bag.

I kissed her cheek. “Thank you, Mrs. Witherspoon.”

Samuel gave me a big hug too. “Farewell, Emeline O’Connor. We’ll take good care of Dakota. Come back and see us.”

“I will,” I said, kissing his cheek, too. “And, thank you for teaching me about wood carving.”

I handed over my ticket and climbed the three steps into the railway car. Inside were rows of wooden bench seats with a narrow aisle between them. Two people sat on each side of the car on each row. In the back, there was a community “washroom.” There might have been ten rows, I didn’t count them, but I found an open seat by a window, which was opened for fresh air. I removed my rucksack from my back, placed it under my feet, and sat down.

After a few more minutes, I heard the train bell. Ding, ding. ding, ding. Ding, ding. A long, low whistle followed: toooot, toot, toot, toooot. Then I heard a chuffing sound as the steam started pushing and the wheels squealed, grinding against the metal rails. I smiled and waved to the Witherspoons and they waved back. The chuffing got faster and faster. The squealing stopped, except for around curves. I watched the countryside go by in a flash. I was finally on my way again!