Chapter Twelve

The End of the Road: British Sea Power in the Post-war World

If the sea power related closely to balanced economic growth in the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the age of commercial capitalism, then the proposition would hold a fortiori for the twentieth century, the age of industrial capitalism … We need only compare the procurement lists of the Royal Navy today with a century ago to appreciate the point.

J. J. Clarke, ‘Merchant Navy and the Navy: A Note on the Mahan Hypothesis’,

Royal United Services Institution Journal,

cxii, no. 646 (May 1967), p. 163.

The decline in Britain’s position as a world power and the consequent reduction of her naval strength throughout the globe began, as we have seen, a little before the Diamond Jubilee year of 1897. But, thanks to the two world wars, the pace of this withdrawal in the twentieth century was never a steady one. Although strategical disengagement from many overseas commitments together with the threat from the German fleet saw the greater part of the Royal Navy already concentrated in the North Sea by 1914, the First World War itself resulted in an extension of the British Empire. That this fresh expansion was simply too great for Britain’s real strength to manage, and ran in contradiction to its steadily deteriorating potential as a Great Power, was tacitly acknowledged by the Washington treaties of the 1920s and by the Chiefs of Staff and the Treasury in the 1930s, when both warned of the consequences of fighting a prolonged modern war against one or more of the dictatorships. Nevertheless the exigencies of war again forced the British into a worldwide struggle which left them in 1945 in possession of many territories overseas and enormous armed forces to defend them. Once more, however, this imposing appearance was not justified by the realities of power, for Britain had severely overstrained herself in the effort to survive. As a consequence, the post-1945 period witnessed the final and greatest contraction of all. Those long-term trends detected earlier – the relative weakening of the British economy, the rise of the super-powers, the disintegration of the European empires, the decline of sea power in its classical form vis-à-vis land and air power, the growing public demand for increased domestic rather than foreign expenditure – now combined finally to overwhelm a British naval mastery that had long been in question.1

To British politicians and military leaders in 1945, however, the inevitability of a swift withdrawal was not so apparent as it has become thirty years later.2 In the first place, there still lingered that habit of regarding Britain as one of the ‘Big Three’, or at least as possessing a particularly important place in Europe, Asia and Africa – an attitude of mind not challenged by much of the British Press and in some way reinforced by the fact that fellow second-grade powers such as France, Germany and Japan had been devastated or at least severely hit by the war. Secondly, the coming of the Cold War and the real or imaginary threat from Communism throughout the globe, together with guilt feelings about the ‘Appeasement’ of the 1930s, combined to prevent any swift running-down of British defence forces on the lines of the post-1815 and post-1919 retrenchments.3 In addition, the Second World War had been the catalyst for a widespread outburst of nationalistic agitation in the colonial world, which prompted the diversion of British troops, fresh from their wartime victories against modern powers, into a variety of ‘peace-keeping’ roles in the tropics against indigenous revolutionaries: the terrorism in Palestine and the Hindu-Muslim rivalry in India were only the greatest of these problems but there were many others, in Egypt, Burma, Malaya and elsewhere. The sheer fact of victory had also added to the number of troops stationed overseas. Apart from the considerable garrisons in Germany, Italy and Austria, there were forces in Greece, the greater part of North Africa, Iraq, East Africa, Indo-China, Siam and the Dutch East Indies. In view of all this it was scarcely surprising that a swift retreat from Britain’s overseas responsibilities was not widely envisaged in the aftermath of VE Day.

Nevertheless while certain realities pressed the British to stay others pressed them to go. Choosing which of these to respond to was a particularly difficult task, and it is only fair to point out that much of the confusion and untidiness attached to British defence policy in the twenty years following the war was caused by the complexities of the political, strategic and technological problems that arose: no solution was simple or could be taken without grave risks. The world, and Britain’s position in it, had been greatly changed, but the dust had not subsided enough for statesmen to see clearly how much of the earlier structure remained. Reluctantly, and often very slowly, the extent of the transformation – and the greater strength of the pressures to go – were realized; but sometimes the British government failed to recall Salisbury’s adage that nothing was more disastrous in a changing scene than clinging to the carcasses of past policies. Step by step the British retreated – or rather stumbled – back to their island base, whence they had emerged some two or more centuries earlier to dominate a great part of the globe and its oceans.

Of all the various stages in this withdrawal, there is little doubt that the most decisive occurred in 1947, when the British government fulfilled long-standing pledges and pulled out of the Indian sub-continent. It would be erroneous, however, to see this act as being motivated solely by the Labour Party’s well-known opposition to imperialism. Attlee and his colleagues shared the Tories’ fear of the consequences of a premature withdrawal, yet they were moved by other practical considerations, too: as Dalton, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, put it, ‘If you are in a place where you are not wanted and where you have not got the force to squash those who don’t want you, the only thing is to get out.’4 It was about the same time that Bevin also announced the British government’s intention to abandon Palestine and declined to renew the commitments to support Greece and Turkey. Whether the withdrawal from India was a virtue or a necessity, however, one thing was clear: the British Empire, of which India had for almost two centuries been the centre-piece, was coming to an end. The retreat from India, cherished by Victorian statesmen as ‘the grand base of British power in the East’,5 and the consequent loss of the Indian Army, undermined both the raison d’être and the manpower for those many British posts elsewhere, which had been acquired to protect the lines of communication to that most precious possession. Had not Curzon declared in 1907:

When India has gone and the great Colonies have gone, do you suppose that we can stop there? Your ports and coaling stations, your fortresses and dockyards, your Crown Colonies and protectorates will go too. For either they will be unnecessary as the toll-gates and barbicans of an empire that has vanished, or they will be taken by an enemy more powerful than yourselves.6

It is therefore astonishing to learn that ‘no reappraisal [of British defence policy] ever took place’ following the abandonment of the Indian subcontinent.7 Once again, traditional patterns of thought, an inadequate decision-making process and a concentration upon issues elsewhere, prevented any fundamental alteration in attitudes or policies – with deleterious consequences for the future. Because there were no considered long-term assessments of Britain’s place in the world, of the processes of decolonization, and of the changing global military balance, her forces were compelled to fight a whole series of ad hoc ‘brush-fire’ wars and to be mobilized for various confrontations in the tropics: Malaya, Kenya, Suez, Kuweit, North Borneo, Cyprus, Aden, the Trucial States, East Africa, the Falkland Islands, British Honduras, Mauritius, the sheer number and geographical disparity of such places being yet another reflection of the overstretched imperial structure that the British had erected in happier days. Some of these actions were small and are now almost forgotten about; others were far larger and even today evoke memories of pain or pride. Some were judged to be very successful at the time, a tribute to the mobility and still appreciable strength of Britain’s defence forces – against natives; others were humiliating failures. But even the successful encounters were often followed by events which negated their meaning: revolutionary leaders were recognized as heads of state; agreements were made with once hostile nations, which turned them overnight into friends; and the overall effect of such British interventions was more to act as a delaying force, to create ‘stability’ for a certain length of time, than to herald a return to the days of gunboat diplomacy. They were the death spasms of a sinking empire – frequent and large-scale at first, but slowly ebbing away as the patient’s strength became exhausted and his muscles atrophied. One might detect the last shudder in Harold Wilson’s announcement of 16 January 1968 that British forces would be withdrawn from the Far East and the Persian Gulf by 1971, for the marginal amendments made by the succeeding Conservative administration could hardly be said to have revived the corpse.

The steady process of imperial disintegration meant that one aspect of Mahan’s now anachronistic three-sided recipe for sea power – colonies, which facilitate and protect shipping – had completely collapsed. This, too, was simply the culmination of an already well-developed movement; the Second World War, as we have seen in the previous chapter, had merely exposed to open view the strategical disunity of the Empire. With the granting of freedom to India, however, the whole notion of ‘imperial’ defence came to an end: the Empire might be transformed into the Commonwealth, but the successor body could in no way retain even the patched-up political cohesion of the inter-war years. India under Nehru and Mrs Gandhi became neutralist, frowning upon the presence of all Great Powers in the Indian Ocean; regarded the United Nations as a much more meaningful forum for international debates; and even went to war against another Commonwealth member, Pakistan. Development aid and cultural interchanges became the sole remnants of that dream of federation pursued by Seeley, Chamberlain and the rest. That Australia and New Zealand could sign the ANZUS Treaty with the United States in 1951 without much regard to the feelings of hurt and irritation this provoked in Britain indicated the extent to which the myth had been shattered by the hard realities of world politics.8 The very idea that such a widely dispersed group of territories as the British Empire could be moulded into an organic defence unit was only worth contemplating in an age when Britain was financially strong and uninvolved in Europe, when the dependencies valued the links with Whitehall above all others, and when sea power was predominant. By 1945 none of these preconditions applied.

What was more, if the other members of the Commonwealth preferred to concentrate upon their regional political, economic and strategical needs, so too did the British – although here again the decision-making élite in London was torn between various aims, best symbolized by Churchill’s and Eden’s optimistic claim that their country lay conveniently within three circles, represented by the Commonwealth, the United States and Europe. Of these, there was no doubt that the latter was the least popular: links with the former Empire had sunk too deeply into the Englishman’s consciousness to be rejected easily, despite the rebuffs administered by Dominion leaders; the so-called ‘special relationship’ with the United States, forged by the war and possibly increased by the dependence upon Washington afterwards, was something else to bemuse those Britons who did not perceive that it was less valued on the other side of the Atlantic; but Europe had been a hotbed of trouble throughout the century, an encumbrance to foreign policy and to all the efforts to preserve Britain’s freedom of action in world affairs. It was the two interventions in Europe – with their deleterious consequences – which had bled British power white; and with the continent now devastated by the war, with large Communist parties in France and Italy, and with Germany still distrusted, was it not advisable for Britain to maintain her distance politically from that area?9

Yet however attractive these arguments – and the resentment against the Common Market still reveals signs of this attitude – it simply flew in the face of geography, of the British experience since the turn of the century, and especially of the political and military situation in 1945. ‘Splendid isolation’, too, could only be maintained at a time when a continental balance of power existed and British sea power was supreme; when both were undermined, Britain’s stance had to change. The desperate but futile attempts to avoid ‘the continental commitment’ (Howard) in the inter-war years pointed a lesson which had become more and more apparent as land power and air power gained in influence. What was more, the Allied military campaigns into the heart of Europe had presented the British leaders with a virtual fait accompli: it was clearly going to take some time before the European economy and communications were restored, famine averted and Nazism eradicated, all of which prevented an early withdrawal. Most important of all, the British, American and French garrisons in Germany, Italy and Austria were now contiguous to Red Army divisions, under the command of a dictator who seemed to show no signs of respecting the ideals of liberal democracy for which the West had fought the war, and many signs – inside and outside Europe – of wishing to extend Communist influence further. With the Foreign Office concentrating upon checking Russian aims by persuading the United States to remain in Europe, by aiding the recovery of France, and by seeking to rebuild a shattered continent, it was obviously impossible for Britain to wash her hands of an extensive commitment herself.

This basic fact the army, perhaps naturally, was the first to point out. In 1946 Montgomery urged the creation of ‘a strong western bloc’ and the promise by Britain ‘to fight on the mainland of Europe, alongside our allies’.10 It was no more possible to tolerate western and central Europe falling into the hands of Russia now than it had been to have it fall into German hands in 1914 or 1939; and the advent of long-range rockets simply reinforced Baldwin’s point about Britain’s frontier being on the Rhine. Equally natural was the Admiralty’s fight against this line of reasoning, and the implications for the priorities in the country’s defence budget. The debates of 1906–14 and 1920–39 were being fought out again, but this time the historical precedents could merge with the logic of the existing power balance to overwhelm the navy’s appeal to ‘the British way of warfare’. The long struggle to stay uncommitted had ended: the defence of Europe had become the first priority, and the tensions during the coup in Czechoslovakia and the Berlin airlift increased this trend. The signing of the NATO Treaty in 1949 – the most comprehensive military obligation ever undertaken by Britain, and one which reflected above all else the country’s strategic identity with western Europe and strategic dependence upon the United States – was the formal confirmation of this priority. By comparison, the CENTO and SEATO pacts were insignificant affairs, gestures rather than real commitments against Communism, and never taken very seriously by Whitehall subsequently.

As if the Admiralty had not received a crushing enough blow to its hopes and prestige by the identification of a land war – or a nuclear one – as the most likely contingency for Britain’s defence forces to anticipate, it encountered a fundamental challenge to its autonomy by the post-1945 series of decisions (especially those of 1946, 1963 and 1967) to integrate all three armed services into a Ministry of Defence.11 There were, of course, certain precedents for this move, as the activities of the C.I.D. and the Minister for the Coordination of Defence in the 1930s had revealed. The pressing need to allocate Britain’s declining resources in a manner best suited to give her a balanced defence force was the major reason for the new measure, but there were also good strategical ones too. The traditional dichotomy, according to which the army interested itself in the defence of India and the navy in the maintenance of the imperial seaways, had lingered long into the twentieth century and had indeed been accentuated by the bitter quarrels about a continental commitment. A few more percipient writers, like Julian Corbett, had endeavoured to show how much the army and the navy had complemented each other in Britain’s past wars, and how either one acting in isolation possessed a greatly reduced role and effectiveness.12 But it had taken the Second World War, and particularly such operations as the D Day landings, to illustrate once again the need for the services to have a joint strategy in which each would cooperate to achieve their overall aim. The existence of aircraft carriers, the creation of airborne divisions, and the development of amphibious techniques all suggested that the operational roles of the services now overlapped.13 Nevertheless, if there were cogent grounds for this integration, it did mean that the Board of the Admiralty’s special claims to decision-making were ended, and it did imply that the navy could no longer regard itself as the ‘Senior’ service.

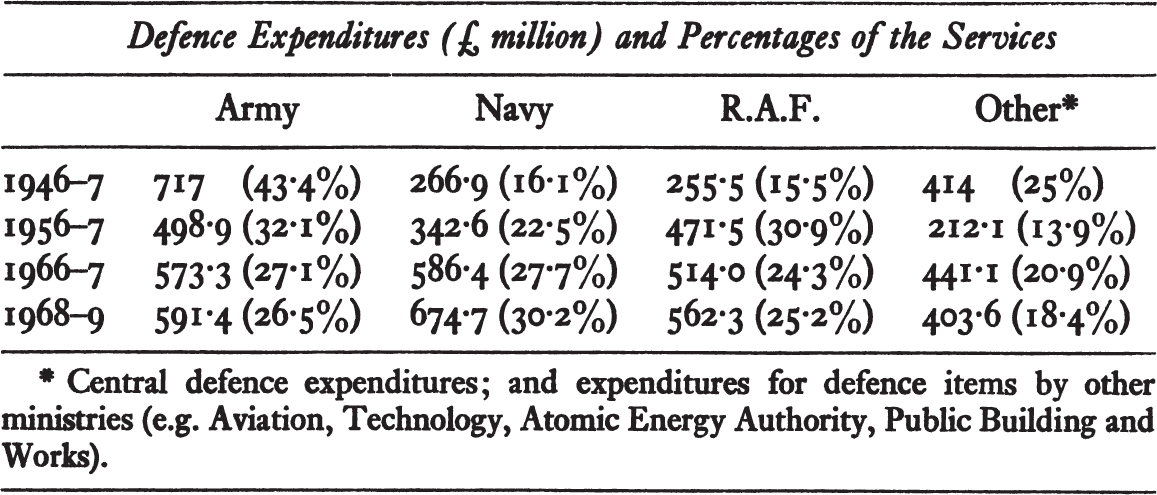

On the other hand a cursory glance at the defence estimates since the war would seem to indicate that in the financial sphere the reverse was true – that the navy’s share of the ‘cake’ was steadily rising. In view of the additional fact that it had been accustomed to receive around £55 million per annum in the 1930s, there would appear to be little cause for concern. Both absolutely and relatively the admirals could be thought to have done well:14

Upon closer examination, however, these figures are less impressive. Wartime and post-war inflation, especially in military hardware and in wages, has eaten away any real gains from the substantial absolute increase in naval expenditure since the pre-1939 period. Moreover, it is a commonplace in the history of British defence policy for the navy’s percentage to rise in peacetime as the large armies were disbanded – which suggests that there is almost an inverse ratio between the importance attached to the army and the navy in peacetime and that attached to both in wartime. In this case the navy’s increased share in the post-war years reflects more the even swifter decline in the army and the R.A.F. than an actual improvement in its own position. The so-called ‘Sandys White Paper’ of 1957, composed in the aftermath of the Suez fiasco and with a firm belief in a massive nuclear deterrent, ran down the large standing army which conscription had produced.15 In regard to the R.A.F. the hopes and then repeated collapses of its plans to establish an effective strategic bombing/missile system – Blue Streak, the Avro 730 bomber, Skybolt, TSR–2, F–111 – account for the rise and subsequent reduction in its proportion of the defence estimates. Measuring the navy’s role and effectiveness by a financial yardstick is likely to be deceptive in the confused post-1945 years, therefore.

A far more meaningful examination of the place of the Royal Navy in British defence strategy today can be achieved by looking at the various obligations and war contingencies which, according to the government’s defence papers,16 the armed forces of the country are designed to meet.

The first of these is the most dreaded of all – nuclear warfare. Here the development of the Hydrogen bomb, of the inter-continental ballistic missile, and of the Russian military and technological capacity has rendered a small, densely populated area like the British Isles extremely vulnerable. In the 1930s it was feared that the bomber had done the same, until the invention of radar and the creation of the Hurricane and Spitfire fighters; but now it seems unlikely that there will be any defence at all for Britain against the horde of fast-travelling missiles with multiple warheads which Russia is able to deploy: about ten Hydrogen bombs would be enough to reduce the country to cinders, and the Soviet defence forces are estimated to have well over 2,000 delivery vehicles at the present time. The obvious conclusions from this were drawn by Whitehall as early as that White Paper of 1957.

It must be frankly recognised that there is at present no means of providing adequate protection for the people of this country against the consequences of an attack with nuclear weapons … the only existing safeguard against major aggression is the power to threaten retaliation with nuclear weapons.17

There was a fearful logic in all this: as Churchill was to put it, safety had to be based upon terror, and survival to rely upon a mutual fear of annihilation. So much has the nuclear deterrent neutralized the ability of either East or West to attack its foe without risk that a virtual strategical stalemate has been established, broken only by the occasional disagreement, which has caused the world to sweat profusely at the possible outcome; and it may be that a more permanent détente can be arranged in the future.

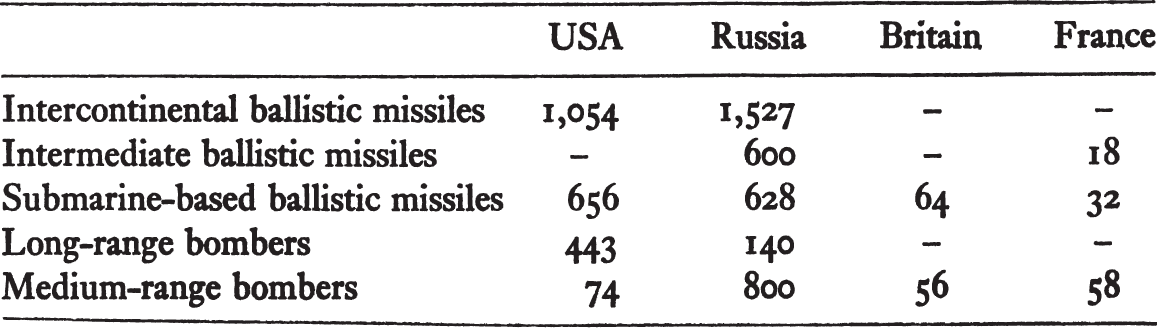

Yet such an East-West agreement between the nuclear states would depend almost exclusively upon the two super-powers Russia and the U.S.A.: Britain’s role, as has so often been the case since 1945, would be marginal and limited. Its efforts to create an independent nuclear deterrent following the McMahon Act and the American refusal to share information about the bomb have been so well chronicled that it would be superfluous to describe them here.18 It is a story of continual disappointments and checks, of cancelled projects and changed decisions, and of an ever-increasing gap between the means and the end; and it now appears probable that the more single-minded French policy will produce better results.19 Nevertheless, both European powers are mere midgets compared with the Big Two, as the latest estimates of nuclear delivery vehicles indicate:20

Indeed, the obsolescence of the V-bombers and the abandonment of the many attempts to build a successor to it that would be both financially and technologically viable would have led to Britain’s dropping out of this ‘nuclear club’ apart from the Polaris submarines. With such vessels, each possessing the capability of firing from under the sea sixteen missiles with nuclear warheads at enemy targets, it would seem that Britain’s position in the table – and the Royal Navy’s claim to a certain distinction – could be justified. Yet here again first assumptions are soon undermined by harsher realities. Polaris is, of course, an American weapon and was only made available to the British by the special Nassau agreement of 1962; and the comparatively low capital and maintenance costs of this system – without which, one suspects, Whitehall would have abandoned the nuclear deterrent there and then – were ‘palpably dependent on American goodwill and assistance’.21 In the advanced technological world of the 1960s and 1970s Britain relies upon American rocketry as much as Turkey and certain Latin American states relied upon Britain for dreadnoughts in the pre-1914 period. Furthermore, doubts have been expressed about whether the force of four Polaris submarines is sufficient to have one vessel on station all the time,22 but there are no signs that the number will be increased. Finally, the impressive recent development of the Russian anti-ballistic missile system has indicated that the Polaris missile will soon need to be replaced by the superior MIRV-type Poseidon – again, an American weapon – if it is to avoid becoming obsolete.23

The second military contingency for which the British armed forces must prepare is the defence of the land frontier of western Europe – the continental commitment at last fully accepted by the stationing of 55,000 troops and eleven R.A.F. squadrons in Germany. Compared with the far larger contributions from the United States, West Germany and other European NATO countries, the British offering is useful rather than decisive, and even a doubling or quadrupling of this commitment would make little impact upon the present imbalance between NATO and the Warsaw Pact powers, with the latter enjoying a great superiority in tactical aircraft, tanks and troops.24 The Soviet deployment of 300,000 troops into Czechoslovakia in 1968 was a grim confirmation of Russia’s capabilities in the crucial central European zone; in the northern zone Russia possesses an even greater superiority over Norwegian forces; and the numerical lead of NATO in the Southern Command area masks many weaknesses in the Mediterranean states. In any case, since European defence involves primarily a commitment of land and air forces, the Royal Navy’s role is minimal (Polaris – and nuclear warfare – always excepted). Only in the guarding of the maritime flanks of Europe do the British occupy a more prominent position.

Since the sea is indivisible, it is probably better that any assessment of Britain’s position in that respect is merged into an examination of its ability to defend its own maritime communications in general, for in both instances Whitehall and its allies face a Soviet naval challenge of gigantic and still-growing proportions.25 In the past two decades the Russians have added to their great land and air power the newer dimension of sea power, and this to an extent which is still generally underestimated in the West. As the editor of Jane’s put it recently,

The plot on the map of the world of the appearances and movements of Soviet warships, represented by red dots, has been likened to a rash of measles but, unlike the spots of the latter which quickly disappear, the red dots are there to stay, for the USSR has learned from the century of Pax Britannica, and the quarter century of American naval predominance which followed, that sea power is national power, international power and deterrent power up to nuclear deterrent power.26

The present Russian Navy consists of ninety-five nuclear-powered submarines, 313 diesel submarines, one carrier, two helicopter-carriers, twelve guided-missile and fifteen gun cruisers, thirty-two guided-missile and sixty-six gun destroyers, 130 frigates, 258 escorts and numerous smaller craft. Only the United States Navy, with its fifteen large attack carriers and many other surface vessels, is superior to it, although the steady decline in the size of that force, its tendency to prefer a few enormously expensive new warships to a myriad of smaller ones, and the domestic political mood in America following the Vietnam war, have caused many observers to wonder if this lead will be maintained in the face of the steady and apparently irreversible Soviet naval growth.

What is unquestioned, at least, is that the Royal Navy alone would be in no position to check the Russian fleet. From a 1945 strength of fifteen battleships and battle-cruisers, seven fleet, four light fleet and forty-one escort carriers, sixty-two cruisers, 131 submarines, 108 fleet destroyers, and 383 escort destroyers and frigates, it has deteriorated to a total of one carrier, two helicopter-carriers, four Polaris, eight other nuclear-powered and twenty-three diesel submarines, two assault ships, two cruisers, ten destroyers and sixty-four frigates; and there is every prospect of a further decrease in the future. Even in a struggle between surface fleets it could not match the Russians, but the greatest weakness lies in the size of its anti-submarine forces. Britain’s dependence upon overseas trade, that Achilles’ Heel of the two world wars, is just as great today, although her ability to protect herself has shrunk alarmingly. In 1939 this country could field 201 destroyers and frigates against forty-nine German U-boats, and still came close to defeat; at present it possesses seventy-four such vessels to face over 400 Russian submarines.27 Add to this the vulnerability to missiles, bombs and torpedoes of all surface vessels, whether merchant or naval, or what Paul Cohen has referred to as ‘the erosion of surface naval power’,28 and the position becomes even grimmer for the West. Small wonder that détente is favoured on strategical as well as financial and political grounds: a war with Russia, whether nuclear or conventional, would be disastrous.

Outside the NATO area the naval situation is far more serious, for the Russian fleet is repeating in distant seas the successes it has gained in the Mediterranean, where its warships shadow and strive to neutralize the predominance of the United States Sixth Fleet and its foreign policy has secured political influence and naval bases in certain Arab states. In the Indian Ocean especially, the activities of the new Russian Navy have created concern29 – the more so because they occur precisely at a time when that region has become almost a power vacuum. With the Royal Navy already mainly withdrawn from an East of Suez role and with the United States aching to abandon that position as the world’s policeman which it took up so readily after 1945, Russian naval forces go eagerly outwards, apparently unhindered by cost, obsolescence or domestic political considerations. Whilst the dependence of the industrialized West upon raw materials and overseas trade grows inexorably, and their merchant fleets are now larger than ever, the capacity to defend the seaways – the first and only real definition of ‘command of the sea’ – has diminished. At the same time the traditional weapon of the naval blockade, even if it could be implemented in the face of Russia’s aircraft, submarines and surface vessels, would have little or no effect upon the economy and fighting capacity of that country.

The fourth strategical objective of Britain’s armed forces is the defence of her territories, interests and obligations outside Europe. In the early years of the Cold War, with Communist threats apparent throughout Asia and the Middle East, this occupied almost as high a priority with the Service chiefs as it had done, say, in 1902 or 1936; and innovations were made in the services to ensure that so-called ‘brush-fire’ wars could be dealt with. Commando carriers, the development of amphibious and airborne units, the teaching of jungle-warfare techniques, all implied that the role of a policeman would continue to be of importance. Kuwait, East Africa and Malaysia appeared to have more relevance than Suez. In recent years, however, this attitude has altered.30 Apart from a few odd islands, the Empire is no more; military interventions overseas would be widely resented in this country, and even more so abroad; Britain’s finances could not stand the strains of a major crisis; and it is doubtful if Whitehall possessed the military muscle-power, let alone the political will, to achieve such an aim. The balance of world power and changes in public opinion are altering too swiftly and decisively to turn the clock back. Only a few years after leaving the Gulf states to look after themselves, for example, Britain was temporarily crippled by their oil embargoes. Nor are the measures attendant upon the ANZUK treaty in South-east Asia likely to reverse this trend: even that navalist organ Jane’s Fighting Ships has admitted that it would be useless now to maintain ‘a worthwhile Fleet in the Far East’.31

Thus, in all four war contingencies in which Britain is thought likely to be involved it is obvious that its defence requirements far exceed its strength, particularly in the naval field. A nuclear war would be a calamity for Britain, nor can its deterrent be regarded as effective as that of other powers: naval forces cannot hold western Europe; neither, in view of the present size of the Russian fleet, could they adequately defend NATO’s maritime flanks and the world-wide lines of communication; and their role and capability in overseas theatres is being pared down rapidly. As Jane’s admitted,

The stark truth is that the Royal Navy has fallen below the safety level required to protect the home islands, to guard the ocean trade routes for the world-deployed mercantile marine …, to protect the vast commerical and financial interests overseas, and to meet the NATO, ANZUK and other treaty commitments.32

It should come as no surprise to learn of the solution put forward by that annual to repair these weaknesses: increase the amount of expenditure upon defence, currently equal to around 5 per cent of Britain’s Gross National Product, to a proportion comparable with that of Russia and the United States (8 per cent). Or, as another naval authority has expressed it,

the major problem … is to provide sufficient forces to enable Britain to meet her obligations which, if she is to retain any semblance of her former greatness, she must do. The nation needs to be made conscious of its heritage and its dependence on sea power for its daily bread and butter.33

Such voices have, of course, been heard many times before in the history of British defence policy: they are the present-day voices of Beatty, Chatfield and their predecessors, a long line of admirals and generals who sought, usually in vain, to convince their political leaders of the magnitude of the potential dangers their country faced, and of the pressing need for more ships and more men. Alternatively they are the voices of an entrenched minority, isolated from those domestic pressures which force politicians into a natural compromise, disapproving of the sums being diverted to the nation’s social and economic requirements, and too prone to suspicions of other powers and to exaggeration of the threats they pose. Between these two extreme beliefs in preparing for everything and preparing for nothing, a sensible middle way has to be sought, for Britain’s rulers can neither pin their hopes upon the assumption that they will never be involved in wars or confrontations in the future nor can they provide for armaments to super-power level. With its relative military strength and role in world affairs shrinking away, and with a too narrow population and industrial base to allow it to provide its own security independently, it must join with its allies to create a common defence; it must, because of its peculiar vulnerability both to military and economic pressures, be the first to encourage an East-West détente and a peaceful solution to the world’s problems; and it must recognize that the age of gunboat diplomacy is over and that negotiation rather than force should be used to protect its overseas interests. It was not the previous policy of Britain, even in its prime, to presume that the rest of the world was hostile and full of malevolent intent, against which it needed to be armed to the teeth; nor should it be now.

Nevertheless, in an unpredictable and ever-changing world in which nation states remain as disposed as ever to protect their ‘vital interests’ by force, it is equally clear that Britain requires a certain minimal level of armed strength: she cannot make up the difference between her peacetime and wartime requirements overnight. And by all the criteria for measuring ends and means, it is also clear that its defence forces are at the present time quite inadequate unless it is to rely almost entirely upon NATO’s nuclear deterrent, which is not only an extremely risky policy but one which is inappropriate in many circumstances.

Yet the cruellest part of this dilemma is that the navalists’ appeals for a somewhat higher share of governmental spending are no real solution. Apart from the domestic political difficulties of such a step at the moment, any foreseeable increases would be negligible in their strategical effects. Would another Polaris-type submarine and a couple of through-deck cruisers, together costing a cool £200 million, much alter Britain’s capability to fulfil the obligations listed above? A much greater, and longer-term, construction programme would be far more logical. But what many of those who nod their heads at this proposition tend to ignore, and what most of the retired rear-admirals who write letters to The Times or Telegraph or present papers to the R.U.S.I. along such lines all too frequently skate over is the simple fact that Britain is too poor to afford any such programme. Even in the inter-war period Chatfield had privately admitted that ‘We literally have not got the income to keep up a first-class Navy.’34 Now it must be admitted that a good second-class navy is also outside the nation’s capacity. For maritime strength depends, as it always did, upon commercial and industrial strength: if the latter is declining relatively, the former is bound to follow. As Britain’s naval rise was rooted in its economic advancement, so too its naval collapse is rooted in its steady loss of economic primacy. We have come full circle.

To explore this truth of Britain’s poor economic performance and its implications for its power position in the post-1945 world in greater detail, as we shall do shortly, is not to imply that this country could have retained in any conceivable way its nineteenth-century predominance. Mackinder was fully correct in arguing that the industrialization of other states with greater populations, area and sources of raw materials would lead to a fundamental shift in the global power-balance and to a relative decline on Britain’s part: to this extent the ability to finance the world’s greatest navy was also bound to be affected. Nor does such an exploration undermine the further major contention of this book that sea power as Mahan and his disciples saw it – sea power based upon the primacy both of national dependence upon oceanic trade and of the largest surface warships to control such commerce – has been overtaken by the development of industrialized land empires and by a host of newer weapons. Those two trends would have ensured the fall of British naval mastery in any case. What follows, therefore, is admittedly of less universal significance: it is to seek to understand why Britain is not likely to possess even a second-rate navy in the future, and why something more fundamental than a simple addition to the defence estimates is required to reverse this decline.

It is all too easy to appreciate how the Second World War affected Britain’s economic strength: the decay of export industries, the loss of overseas markets, the wearing-out of so many machines and the devastation through bombing to plant and property, the loss of invisible earnings and the vast increase in the nation’s debts have been described elsewhere.35 It was this grim financial picture which provoked Keynes’s well-known report to the Cabinet at the end of the European war that Britain was facing ‘a financial Dunkirk’ and that without American aid the trade deficit would be so large that she would be ‘virtually bankrupt and the economic basis for the hopes of the public non-existent’.36 The virtual cancellation of the Lend-Lease obligations and the long-term American loan of $3,750 million at the end of 1945 proved welcome aids, therefore, but the attached condition that Whitehall should soon arrange free convertibility of sterling revealed that the United States still harboured its wartime financial aims and its overestimation of British economic strength; indeed, one scholar has argued that Washington put its ‘junior partner’ in an impossible position by weakening Britain’s capacity to remain in such places as the Middle East yet still wanting her stabilizing presence there.37 The economic crisis which occurred in 1947, when convertibility was permitted, indicated how unfavourably Britain’s chances were regarded in the international financial market. Even the massive devaluation of the pound which followed the next crisis in 1949 provided only temporary relief, for the Korean War – where defence expenditure jumped to 9.9 per cent of G.N.P. – had its inevitable effect upon export trades and commodity prices. To this posture of Cold War preparedness could be added the burden upon the balance of payments of the high military expenditure overseas, which reached £140 million in 1952 and £215 million in 1960 (whereas total governmental expenditure abroad in 1938 had been £16 million). Here again, it appeared that the over-extension of Britain’s strength caused by the wartime victory and maintained as a result of the international tensions after it, severely hindered the creation of a balanced economy.

This conclusion is, however, only part of the story, for the war was less a catalyst upon Britain’s position than an additional burden upon an economy already exhibiting to an increasing degree those trends of the later nineteenth century which were examined earlier: a widespread refusal to recognize that the traditional attitudes and methods of management and trade unions required modification; an inability to exploit new ideas and techniques adequately; shoddy workmanship and poor salesmanship; a distaste for science, technology and commerce in education and public life; a depressingly low rate of investment; poor labour relations; and a propensity for the nation to spend more than it was earning. It is only after appreciating the importance of these longer-term traits that one should add the more recent reasons of overseas military expenditure; the decrease in that ‘cushion’ of invisible earnings, followed by the further loss of imperial markets; and the change in the terms of trade, and in particular the hefty rises in the price of such a vital raw material as oil, to Britain’s detriment. For if the British were burdened by economic problems in 1945, their situation could hardly be compared with that of the Japanese, Germans and other peoples whose commerce and industry had been almost eradicated. No amount of pointing to the effects of the war upon Britain can explain away the fact that nations hit far more severely have flourished economically since, while she has not. Almost every figure relating to manufacturing productivity in the post-war period – whether national rates of growth, rises in output per man-hour, capital formation and investment, and exports – has shown Britain to be at or near the bottom of the table of industrialized powers. Her share of the world’s export of manufactures, for example, slumped from 29.3 per cent in 1948 to 12.9 per cent in 1966.38

This reminds us once again that we are examining the relative success of economies; in absolute terms the years since the war have witnessed widespread and very great advances in the wealth of the British people, while it is also true that many industries are efficient and that the country is exporting proportionately more today than at any time in the past century. Nevertheless, it is little comfort to learn that the British are becoming, in relative terms, the ‘peasants of Europe’. Not only is that position unenviable in itself, but its implications for the country’s military potential are grim. Finally, some pundits, such as the economic editor of The Times, have argued gloomily that the slow growth and cyclical ‘stop-go’ course of the economy in the past twenty-five years actually represents a golden age, for

the evidence is that each cycle is more difficult to sustain than the last, that the periods of “go” get shorter, that the peak rate of inflation gets higher, that the nadir of the balance of payments gets deeper and that the peak and average levels of unemployment get higher. Government policies yaw in a progressively narrower and more frantic zig-zag between the converging limits of “stop” and “go”.39

Intertwined with, and possibly as fundamental as, this poor economic performance were certain psychological changes. The first, that general turning-away from a desire to play an imperial and Great Power role – perhaps best symbolized by Attlee’s replacement of Churchill as Prime Minister in 1945 and the subsequent social innovations of the Labour Government – is a readily identifiable one. It is worth noting, however, that this movement is deeper than the parallel retraction of Britain’s military commitments, for the transfer of loyalties by the ‘official mind’ from the Empire to Europe has not been followed by the nation at large: entry into the Common Market is more an issue of contention than of agreement. Dean Acheson’s pointed remark that ‘Great Britain has lost an Empire and has yet to find a role’ still applies, therefore, and it will continue to do so until the present introspective mood is replaced by something less self-pitying and xenophobic. Foreign and military affairs of any sort are inevitably of less interest to the public than domestic political and social matters, but this is particularly so when the management of the economy has become so contentious an issue. In such a situation it is hardly surprising that internal quarrels have increased and that the country appears divided: the middle classes have lost that remarkable self-confidence which took them to the ends of the earth, and remain troubled and uncertain; the working classes display either a widespread apathy or, in the case of well-organized trade unions, a militancy not seen since the 1920s; the political system itself provokes cynicism and disillusionment; religion has declined without being replaced by any fresh ‘opium’ (which Marx, contrary to common belief, recognized that a people needs); excessive nostalgia, or neophilia, is evident. With this general malaise affecting the economic aspect, and the latter simultaneously acting upon the public’s mood, it is often difficult to separate cause from effect. Such manifestations are not, of course, unique to Britain; but they seem more deeply rooted here, so much so that Europeans can refer with pity or alarm to ‘the English sickness’.

These symptoms of relative economic decline, national introversion and domestic political dissensions are easily recognizable to scholars of world history: they represent fairly common characteristics of an empire in decline. In this respect it is interesting to note those shared economic and psychological developments detected by Carlo Cipolla in his summary of the decline of the Roman, Byzantine, Arab, Spanish, Italian, Ottoman, Dutch and Chinese Empires:

Whenever we look at declining empires, we notice that their economies are generally faltering. The economic difficulties of declining empires show striking resemblances. All empires seem eventually to develop an intractable resistance to the change needed for the required growth of production. Then neither the needed enterprise, nor the needed type of investment, nor the needed technological change is forthcoming. Why? What we have to admit is that what appears ex post as an obsolete behaviour pattern was, at an earlier stage in the life of an empire, a successful way of doing things, of which the members of the empire were proud … To change our way of working and doing business implies a more general change of customs, attitudes, motivations and sets of values which represent our cultural heritage … If the necessary change does not take place and economic difficulties are allowed to grow, then a cumulative process is bound to be set into motion that makes things progressively worse. Decline enters then in its final, dramatic stage. When needs outstrip production capability, a number of tensions are bound to appear in society. Inflation, excessive taxation, difficulties in the balance of payments are just a small sample of the whole series of possible tensions. The public sector presses heavily over and against the private sector in order to squeeze out the largest possible share of resources. Consumption competes with investment and vice versa. Within the private sector, the conflict among social groups becomes more bitter because each group tries to avoid as much as possible the necessary economic sacrifices. As the struggle grows in bitterness, cooperation among people and social groups fades away, a sense of alienation from the commonwealth develops, and with it group and class selfishness.40

Further comment upon these historical precedents would be superfluous.

The post-war years have also seen an acceleration of governmental expenditure upon social and economic needs, with the amount allocated to defence falling proportionately – another sign, perhaps, of national introvertedness, although an inevitable development in a democratic society where the normal man is preoccupied with more immediate concerns than foreign policies. Gone for ever are the days of Fisher, when, in 1905, £36.8 million could be spent upon the navy and £29.2 million upon the army, whereas only £28 million was devoted to the government’s civilian services of all kinds.41 Even in the inter-war years the balance had shifted dramatically, and since the Korean War and Suez crisis defence expenditure has continued to decrease relatively, as the following table overleaf shows.42

Only another national emergency, it seems clear, would reverse this trend. In an age of détente especially, it is difficult to make out a case for large defence expenditure when there are so many domestic needs which appear more pressing than the country’s external requirements. This Mahan himself had forecast, rather gloomily, when he wrote:

Whether a democratic government will have the foresight, the keen sensitiveness to national position and credit, the willingness to ensure its prosperity by adequate outpouring of money in times of peace, all which are necessary for military preparations, is yet an open question. Popular governments are not generally favourable to military expenditure, however necessary, and there are signs that England tends to drop behind.43

Another long-term tendency which is having serious effects upon British military strength is the sheer costliness of modern armaments. This, too, is not a phenomenon unique to Britain, but it would be true to say that a country financially weak and with great inflationary and balance-of-payments problems is less well-equipped to deal with it than others. The Dreadnought, the first British nuclear-powered submarine, cost over £18 million; a few years later the Polaris-type boats, such as the Resolution, cost £40 million but that was without the missile system. With the latter the cost soared to £52–5 million per vessel and it would no doubt have been far higher but for American assistance. The aircraft carrier Eagle, which cost £15¾ million when new, was refitted in the early 1960s for £31 million. The Type 42 guided-missile destroyers cost £17 million each, and the Type 82 Bristol costs £27 million; with each new model the increase in price is steeper. It is perfectly true that these vessels are far more advanced and pack a far greater punch than their equivalents of 1914–18 or 1939–45, but it is equally true that an increasing amount of money has to be concentrated upon a smaller number of warships although Britain’s merchant fleet and oceanic lines of communication have not shrunk but increased in size. The building of major warships is now financially impossible without vast resources: the American nuclear-powered guided-missile cruiser Long Beach cost $332 million, the latest nuclear-powered attack cruiser is estimated to cost $1 billion, and tentative figures for the Trident-type submarine (with a complex very-long-range missile system to replace existing boats) have produced a similar estimate – $1 billion for one submarine!44

Furthermore, since the ending of national conscription in Britain the services have had to compete with the rates of pay offered by industry, with the result that the proportion of the defence budget devoted to equipment is much reduced: in 1972, for example, £1,567 million (57.9 per cent) of British defence expenditure was allocated to pay, allowances and maintenance, with only £624 million (24.9 per cent) to ‘Procurement’ and £307 million (5.9 per cent) to research and development.45 In the future the share which equipment can expect to secure will probably drop further.

The consequences of all these financial pressures upon Britain’s ability to maintain adequate defence forces and her previous role in the world are twofold. In the first place there are those many instances of where she was forced to retreat from overseas territories because the cost was too great, or compelled to abandon new weapons due to their rising prices and to general budgetary considerations:46 the ‘large army’ policy of national conscription was scrapped chiefly because of the costs (although the result of voluntary recruitment, as mentioned above, has not been to reduce this figure); the burden upon the balance of payments of such events as the Indonesian confrontation led to demands for a withdrawal from that part of the world; weapon systems such as the TSR-2 were cancelled due to their costs escalating beyond the country’s capacity to pay for them; the 1966 Defence White Paper came out against the construction of new carriers because of the Treasury’s insistence that the defence budget should not exceed £2,000 million; the Eagle, despite its refit in the early 1960s, required another modernization to remain on terms with the Ark Royal and when this was found to be too expensive she was paid off, with the Fleet Air Arm thereby ‘ceasing to exist’;47 after the construction costs of the Type 82 destroyer were seen to total £27 million, the plan to build another three was abandoned; the same may occur to the proposed through-deck cruisers after the news that they could each cost £65 million. The best-known example of all is probably that series of decisions made by the Labour government in 1967–8 as a result of the grave economic crisis: the abandonment of the ‘East of Suez’ policy with its expensive bases in the Persian Gulf and Far East, the cancellation of the F-111 aircraft, the reduction in the personnel of the armed forces and the earlier phasing-out of the carriers, were body-blows from which the services have not recovered.

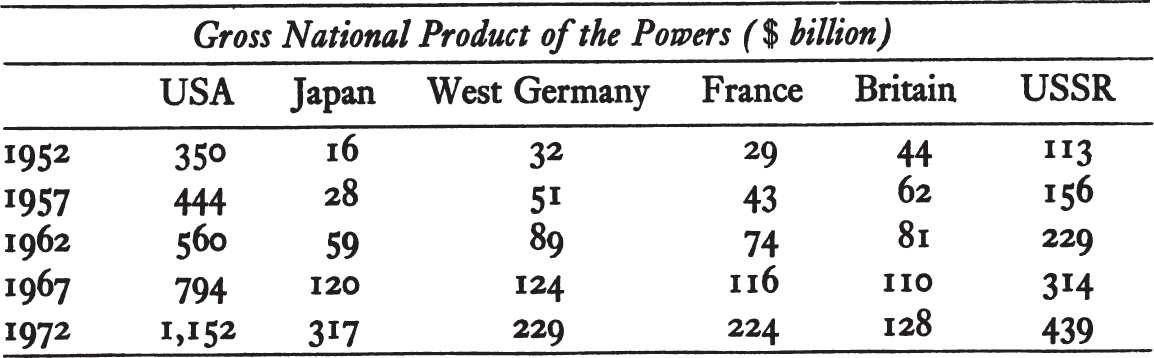

The second consequence concerns Britain’s relative ability to afford adequate defence forces. Other countries, too, experience inflation, the hideous rise in the costs of new weapons, and domestic pressures for improved social services; but if their industrial and financial strength is increasing far more swiftly than Britain’s, they will find it easier to pay for both civil and military requirements. Sharing the cake, in other words, is less contentious an exercise when the cake is always growing in size. The following figures are therefore the most significant of all in our attempt to comprehend Britain’s recent decline:48

From being in third position in 1952 Britain is now sixth and falling further behind every year, with obvious military and political results. To provide defence forces equivalent to those of West Germany, France and other comparable second-class powers, she has to devote a larger proportion of her G.N.P. to military expenditure: like Austria-Hungary before 1914, she must struggle to maintain her place. For example, the Federal German Republic’s defence budget in 1972 of $7,668 million equalled only 2.9 per cent of G.N.P., whereas Britain’s smaller total of $6,968 represented 4.6 per cent of G.N.P. French defence spending, which equalled 3.1 per cent of G.N.P. despite being only slightly less in absolute terms than Britain’s, will rise steadily with that country’s economic growth, so that she will not only possess more ballistic-missile submarines than Britain but is also likely to have the world’s third most powerful navy before much longer.49 Japan, which spent a mere 0.9 per cent of G.N.P. upon defence in 1972, would possess a colossal navy, if ever it raised this proportion to Britain’s level. All this leaves Whitehall in the uncomfortable dilemma of either slashing expenditure upon defence forces, which are already inadequate to carry out their professed tasks, or of facing the political and economic consequences of devoting far more upon armaments than other industrial states of a comparable size and population.

Nor is it likely, according to those economic forecasters who peer into the mists of the future, that such a gloomy trend will alter. It is not too difficult for the historian to point out how often similar sorts of predictions have proved wrong in the past, due to unforeseen political developments; thus, Hermann Kahn’s belief that Japan’s G.N.P. could exceed that of the U.S.A. by the end of this century may have received a fatal blow from the present world oil crisis. It is less easy to ignore his point that the list of twelve ‘qualitative-quantitative’ reasons for this growth to continue still apply in reverse to Great Britain.50 The terms of trade, too, seem destined to worsen in the future. Perhaps the ‘oil miracle’ in the North Sea may effect a transformation; perhaps, although it is less likely, the consequences of joining the Common Market will also bring great benefits. Most of the signs, however, indicate that a fundamental alteration in Britain’s growth rate, and wealth, and defence capacity, probably requires an equally basic change in attitudes and assumptions.

But this is moving away from the tangible facts of politics and economics into the intangibles of mass psychology; and from the established data of the past and the present into the unpredictable realm of the future. In both cases the historian has either to abandon his discipline or to cease writing. I prefer the latter. For whatever the future holds for the British, it is clear that the period in which they strove for, and achieved, naval mastery has finally come to a close. Maritime warfare along the traditional lines, and Britain’s position in the world, have been irrevocably transformed in this past hundred years. Whether she is in the future to remain under the American ‘umbrella’ or to merge with European allies in an integrated defence unit, whether she will settle the relationship between the various services and arrive at a satisfactory solution respecting the use of conventional and nuclear weapons, all questions which are anxiously debated today,51 shrink into their proper perspective when compared with the larger movement we have traced of the rise and fall of Britain as an independent world naval power. Since she is no longer the latter, this story can safely be brought to its conclusion.