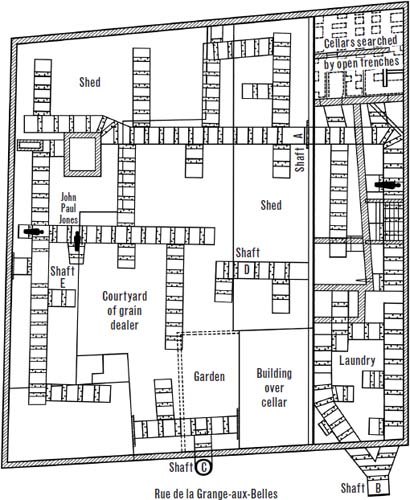

THE WORK PROCEEDED IN ghoulish tedium. A second shaft was sunk through the street in front of the laundry, followed shortly afterward by a third shaft in the street near the entrance to the courtyard behind the granary. Two more shafts were then dug, one through the floor of a granary shed and the last in the courtyard near what would have been the back wall of the cemetery. Each shaft, beginning with the first one, was given a letter in order: Shaft A, Shaft B, and so on. The site was a hive of activity. And it was difficult work. The soil reeked of the long dead—“mephitic odors,” Porter called them—and groundwater seeped in at such a pace the workers had to install pumps.

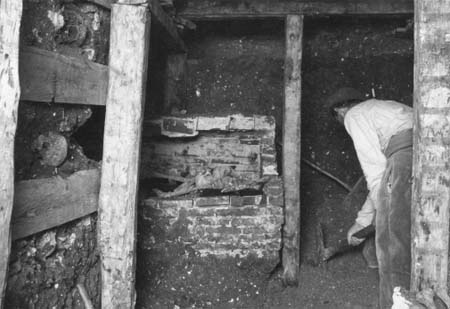

The tunnels at first were extended like exploratory tentacles, which meant they dead-ended, a design that created poor air circulation. Because of the instability of the earth, the men installed squared wooden girders to hold up a protective wooden roof and to brace sideboards that kept the crumbling dirt walls from closing in. They worked by dim candlelight amid the stench, the slop at their feet, the chill, and the stagnant air. As the men dug, they unearthed massive red earthworms, bones, leering skulls—visions they were apt to revisit in their deepest sleep.

Once the first tunnel reached the old garden wall, the workers backtracked a bit and struck out in perpendicular directions, roughly paralleling the wall. In the basement of the laundry, another crew went to work in the back corner, digging an open pit in search of coffins. The crew digging Shaft B out in the street was aiming to tunnel into the property and meet up with the crews working off Shaft A. There was a logic to the scramble. Combined, the three work sites would cover the entire front section of the old cemetery, the place where Porter thought Jones’s body was most likely buried.

In the first few days, they struck a cluster of corpses from a mass burial. There were three layers of skeletons, dozens of them, stacked in a crisscrossing pattern like cordwood, “some lying facedown, others on their sides.” The searchers were confused at first. Then Porter recalled journalistic paintings by Etienne Bericourt that detailed the loading onto carts of the Swiss Guardsmen killed just three weeks after Jones’s death. As Protestants, the Swiss soldiers would not have been buried in any of the Catholic cemeteries. These stacked bones, Porter concluded, were the remains of those men, and he interpreted the discovery as “another proof that although the cemetery was closed soon after [Jones’s] death there was plenty of room left for his coffin at the time of his burial, for the reason that so many bodies were interred there afterward.”

Porter showed up regularly at the work site, seeking updates or just watching, even as official duties kept his calendar full. Less than two weeks before the tunneling had begun, a group of about three thousand unarmed protesters in Saint Petersburg had marched toward the Winter Palace to deliver a petition to Tsar Nicholas II. They were met by the Imperial Guard, which opened fire, killing (depending on the source) anywhere from one hundred to one thousand people. The violence set in motion the events that led to the unsuccessful Russian revolution later that year, and the eventually successful Bolshevik Revolution in 1917.

The political violence wasn’t limited to Russia—the tsar’s gunning down of his own people inflamed anarchists and revolutionaries across Europe and the United States. In Paris, presumed anarchists placed a bomb against the outside wall of the home of Prince Troubetzkoy, a member of the Russian aristocracy and a long-standing attaché to the Russian embassy. A policeman spotted the device and snuffed the fuse before it could explode. That same night, as a meeting of anti-tsarist socialists was breaking up, someone tossed a nail-laden bomb into a throng of police officers, injuring two of them and three civilians. The attacks, along with a wave of hoaxes, set off fears that the city was headed toward another “dynamite club” era, a cycle of bombings and assassinations.

Final layout of the excavation site, within the bounds of the old cemetery. Silhouettes indicate where the first three lead coffins were found.

Original excavation plans in Charles W. Stewart, John Paul Jones: Commemoration at Annapolis, April 24, 1906 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1907); adapted by James Spence

The French were dealing with their own political crises as well. A domestic showdown pitted aristocratic and conservative supporters of the Roman Catholic Church against liberals who sought a separation between church and state. And a growing number of scandals surrounding reported abuses by French officials in Africa emerged: beheading tribal chiefs, executing a tribesman by strapping a stick of dynamite to his back, and force-feeding human flesh to tribal prisoners, among other atrocities. Porter’s job was to watch out for American interests amid the turmoil, and there was much to keep track of with war still raging between the Russians and the Japanese in the Far East, high-level international financial deals being negotiated in Europe, and run-of-the-mill trade issues.1

Porter had personal business to tend to as well. On the evening of March 2, a Thursday, the “great rooms” of the ambassador’s residence, closed since Sophie’s death, were opened once more for a party, a rare social celebration in Porter’s life as a widower. And there was indeed something to celebrate: Porter’s daughter, Elsie, was to marry Dr. Edwin Mende the next morning in a small civil ceremony, to be followed Saturday—which was also Sophie’s birthday—with a public ceremony at the American Church. The focal point of the party, beyond the food and the drinks, was the presentation of gifts, and it was immediately clear that the gifts bestowed on an ambassador’s daughter and her wealthy beau were not the traditional household items. The French government sent over a monogrammed Sevres tea set from the government’s famous porcelain factory. George J. Gould, the railroad tycoon and son of financier Jay Gould, gave a sapphire ring. Secretary Hay and his wife sent a silver tray; Prince von Radolin, the German ambassador, and his wife gave gold bonbonnieres (small boxes); Porter’s old friend General Winslow and his wife gave a gold chocolate service. The parents of the couple were even more generous. Porter gave them a car. The elder Dr. Mende gave them a house in Bern, sealing the couple’s decision to give up on their plans to move to New York City and instead settle in Mende’s home country—a decision that Porter received with “shock,” given that he had predicated his retirement on the idea that the family would be reunited in Manhattan.2

The wedding was the event of the season. An international array of government officials, high society expatriates, and European business leaders filed into the American church, decorated for the day with spring-like arrangements of foliage and flowers. The choir was rounded out with such voices as Bessie Abbott, the young American prima donna of the current Parisian opera season. The bridesmaids wore “dainty green and pink costumes, with broad-bred hats and sweeping plumes,” the New York Times reported. Elsie wore a white satin dress “trimmed with lace and sprays of orange blossoms.” The two-hour reception followed at the ambassador’s residence in what turned out to be the last big party of his six-year stay in the City of Light.3

Meanwhile, Porter was planning his own departure. The White House had announced on February 10 that while Porter would likely remain in France for a few months, Robert McCormick, the current US ambassador to Russia, would be replacing him. Porter was also watching for news from Washington about Roosevelt’s request for Congress to pay for the search for Jones’s body. On February 13 he wired an update on the excavations and a query to Hay: “Sunk shaft. Found rows of dead undisturbed in cemetery at depth seventeen feet. What action taken on my recommendation of John Paul Jones appropriation?” He received a response from Francis Loomis, the assistant secretary of state: “The President sent message to Congress today recommending thirty five thousand dollars for John Paul Jones.”

Roosevelt himself wrote to Porter the next day, thanking him for his work as ambassador. “I appreciate all that you have done in your post; and you can not be more pleased at being connected with my administration than I am at having you under me. But I understand thoroughly the pressing personal reasons you set out in your letter to Secretary Hay, which made it obligatory to leave.” Roosevelt said he toyed with asking Porter to stay on into the summer but decided to accept his resignation effective April 30, a date that meshed with other anticipated diplomatic shuffles.4

Porter then apparently fell out of the loop of communications about his successor. In the weeks after Elsie’s wedding, press accounts reported that McCormick would be heading to Paris sooner than anticipated, a development that seemed to catch Porter unaware. “I saw by press dispatch that McCormick is instructed to proceed to Paris at once and assume charge at early day,” he wired Hay on March 25. “The President having written me that my resignation was accepted as of April 30, I made arrangements accordingly both here and with McCormick. What foundation for above rumor? Porter.”5

Throughout the private and public wedding celebrations, Porter’s conversations with his superiors in Washington about when he could come home, and the daily diplomatic distractions, Weiss’s work crews continued their search. Parisians gathered daily at the site, sometimes joined by Porter, even though there was little for the public to see—most of the work was happening underground. On the surface, workers came and went, and loads of dirt were moved to the street and then loaded onto carts to be hauled away to the storage field. Journalists occasionally popped in, but the newspapers had little to show for it. In fact, the Parisian press largely ignored Porter’s project, and reports from the American foreign correspondents rarely mentioned the dig.

Porter had left strict orders that he was to be summoned at the first sighting of any lead coffins, and on the afternoon of February 22, nearly three weeks after the first dirt was turned, Porter received the call. He hurried from the embassy to the excavation site, crawled down the ladder (probably Shaft A), and made his way to the discovery.

The location of the coffin was encouraging: it was near where the old steps descended from the gate between the orchard and the cemetery, meaning the grave could have been one of the last to be filled, which Porter had speculated would be the case for Jones’s body. The condition of the coffin itself was discouraging. It was lead, but it had been heavily damaged—the rounded “head” of the coffin had been sheared off, along with the skull of the corpse. The damage was old, and Weiss’s excavators also found the remnants of a wooden barrel at the head of the coffin. Porter and Weiss surmised it had been sunk below ground as a catch basin to hold runoff rain to water a garden, damaging the coffin as the barrel was sunk into place. With the coffin split open, its contents exposed to the subterranean moisture, worms, and bacteria, the decapitated remains had been reduced to rotted flesh on bones.

The lead coffin was buried inside a wooden casket, which bore a rusted copper nameplate “so brittle that when lifted it broke and a portion of it crumbled to pieces.” Working gingerly in the flickering candlelight, Porter tried to discern shadows of letters beneath the crusted green patina. None were legible. He carefully wrapped the shim of metal in his handkerchief, tucked it into a coat pocket, and climbed the ladder back out of the growing maze of tunnels. In his time in Paris, Porter had come to know the proprietor of M. André et Fil, an art-restoration business, and he headed there, where he asked the craftsman to work quickly but gently to uncover the name beneath the rust.

That night, Porter delivered a previously scheduled speech to the American Club in Paris and talked about his quest to find Jones’s body. The tenor of the speech made it sound more political than historical, and it is hard to imagine that he was not counting on the foreign correspondents in attendance to wire his words to their newspapers back home. He detailed for the expatriate business leaders his efforts scouring records to find the cemetery in which Jones was likely buried, the more recent negotiations to obtain the right to dig for the body, and the need for Congress to approve the president’s request to pay for the exhumation. Oddly, the Washington Post story on the speech did not mention that the dig had already begun, though that was clearly known both among the expatriates and the foreign correspondents. And it muddled the detail about the first shaft, implying that it had occurred a year before, at the onset of the negotiations with Crignier. If the money wasn’t approved by Congress, the paper reported Porter as saying, the options would lapse and the opportunity would be lost—which was not the case.

“While other nations are gathering the ashes of their heroes in their Pantheons, their Valhallas, and their Westminster Abbeys, all that is mortal of this marvelous organizer of American victories upon the sea lies like an outcast in a squalid quarter of a distant city, in a neglected grave, where it was placed by the hand of charity to keep it from the potter’s field,” Porter told his fellow Americans. “What once was consecrated ground is desecrated by vegetable gardens, a deposit for night soil, and even the burial of dogs. It is fitting that an effort be made to give him an appropriate sepulcher at last in the land of liberty which his efforts helped make free.”6

The search for John Paul Jones’s body, during which workers made their way through layers of skeletons and large red worms, was not for those with weak stomachs. Note the skulls embedded in the earthen wall (left).

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Horace Porter Collection, Manuscript Division

Most of the news reports out of Paris focused on the found coffin and the likelihood that Jones was in it. Speculation turned to probability. The New York Times printed a two-paragraph story the next day reporting that “a metal casket, which is believed to contain the bones of John Paul Jones, has been found 16 feet below a grain shed at 14 Rue Grange aux Belles.” In addition to getting the address wrong, it said Porter and others involved with the dig believed the bones were Jones’s; while they were hopeful, they in fact had no basis to believe it was the right coffin and made no such claim. The story went on to say that the coffin would be opened the next day—another error—and that the “time worn” nameplate was indecipherable.7

But those weren’t Porter’s only problems with the media. From the beginning of the project, Porter had been concerned about intruders at the work site. When the lead coffin was found, he sent word to the prefect of police asking that two officers be assigned to watch over the site, particularly late at night through the early morning, when the workers were gone. “Late in the evening I learned that, owing to his absence from his office and an error in getting the communication to him, there would be no guard there that night,” Porter wrote later. “I could not help feeling some forebodings, and my state of mind may be imagined upon receiving a brief note early the next morning from an official saying he regretted to inform me that there had unfortunately been a depredation committed in the gallery where the leaden coffin was found.”

Porter hurried to the site feeling “like a person who had delayed a day too long in insuring his property and learned that it had taken fire.” But the damage, as it turned out, was minimal. “An enterprising reporter and photographer … had succeeded in opening the gate, getting into the yard, and entering the gallery. In the darkness they had stumbled and broken their [camera] apparatus, and in trying to use one which our men had left in the gallery had broken it also.” Some camera pieces were missing, but otherwise the site was unscathed.

Porter received a report on the nameplate the next day from André, the art restorer, who had been able to work his magic on the severely damaged piece of metal. The front of the nameplate was beyond recovery, so he went to work on the reverse side, which had spent most of its time underground affixed to the wooden casket and thus was less rusted. Working carefully over two days, André cleared away the dirt and sufficient rust to read some of the engraved letters in reverse, enough to conclude that the coffin held the body of an Englishman who had died May 20, 1790, nearly two years before Jones. It was the wrong coffin, he told Porter.

By then, though, press accounts were swirling. “A reporter with a lively imagination could not wait for the deciphering of the plate and meanwhile invented a highly dramatic story,” Porter recalled later. A story appeared saying “there was such certainty entertained that this leaden coffin contained the body of Paul Jones that I had summoned the personnel of the embassy and others to the scene, including the commissary of police who attended ornamented with his tricolored scarf.” The coffin was opened “with great ceremony and solemnity, and the group, deeply affected, stood reverently, with bowed heads, awaiting the recognition of the body of the illustrious sailor” before it became clear that “a serious error had been made.” None of that had happened, and it bothered Porter that the fictitious story had been printed. More importantly, people in some quarters believed the article, leading to criticism that the ambassador and his work crews didn’t know what they were doing and were ready to conclude on the flimsiest evidence that they had succeeded.8

The crews kept digging, but they had little to show for it beyond a deeper and more intricate maze of tunnels. Progress was slow. The area under the laundry was explored, but no other lead coffins were found. The terrain was dangerous and unstable and beleaguered by “infiltrations of water,” Weiss said, so “all the galleries were rapidly and carefully refilled and the work of exploring the property of the grain dealer begun.” The other three shafts were sunk and the galleries were then expanded below ground.

Finally, on March 23, a month after the first lead coffin was found, a crew digging near what had been the back wall of the cemetery discovered another wooden casket with a smaller lead coffin inside. This coffin had a well-preserved nameplate that identified the dead man as RICHARD HAY, ESQ., who had died in January 29, 1785. Not only was it not Jones, but Hay had been buried seven years before Jones, calling into question Porter’s theory that the cemetery had been filled from the center outward. If Porter was disappointed or beginning to question the project, he didn’t reveal it in any surviving records.9

The crews worked on. Eight days later, they hit another lead coffin, this one within a few yards of the second discovered coffin, both near the foot of Shaft E, the last to be sunk. (No explanation could be found as to why it took so long to find the third coffin given its proximity to the second one.) It, too, had been encased in a wooden casket, but this one had suffered the ravages of a century underground. Little of the outer wooden casket was found beyond rotted shards. A skeleton with no coffin of its own was lying atop the lead coffin, and the wooden lid was missing altogether, which meant there also was no nameplate. Workers sifted through the earth excavated from around the coffin but found nothing. Weiss supposed that the lid had been taken up and discarded at the time the coffin-less body had been buried. The workers pulled the coffin and exposed skeleton out of the earth, then carted the metal box to an open area in the gallery. Porter again was summoned.

The ambassador, looking at the crenulated metal, decided to open the lead coffin there underground, in part to dampen public speculation. The air was already so foul that Porter was persuaded to wait, fearing that the added odors from the open coffin would be overpowering in the close, dank space. Crews got to work extending the gallery to connect with a main tunnel emanating from Shaft A, on the opposite side of the cemetery. Once they were connected, this created a ventilation circuit, and the foul air improved considerably. It delayed the opening of the coffin for a week.

Finally, on April 7, Porter was alerted that the site was ready. He brought Bailly-Blanchard with him. Weiss was there too, as was a M. Géninet, Weiss’s on-site supervisor for the project. The visitors all donned long smocks over their suits, and even deep below ground all but Weiss wore bowler hats. The workers took a break and gathered around as well, curious, all, as to what they would find.

The lead coffin had been placed atop a mound of dirt in a low-ceilinged gallery. The years and the weight of fifteen feet or so of earth had crumpled it so that the coffin looked like an elongated can crushed by giant hands. The original shape was still clear, though: narrow at the feet then broadening gradually to the shoulders before narrowing again to a rounded section for the head. There was a small solder plug sealing a hole near the head, and close by was a rough and jagged hole packed with darkened earth. It looked, Porter thought, as though it had been made by the end of a pickax, and he wondered if, sometime after the burial, someone had dug down and struck through the wooden top, piercing the lead coffin below. Maybe it was whoever had buried the skeleton found atop the coffin. There was a second hole in the coffin, too, a small crack near the foot, which Porter concluded had been caused by the shifting and settling of the earth from above. It, too, was packed with darkened dirt.

The coffin had been sealed shut before it was buried, and Porter was concerned that it be protected as much as possible from further damage. So the workers took their time removing the thin line of solder from the seam. When they finished, the top was carefully pried loose and lifted, filling the gallery with the smell of alcohol. There was no liquid, though. It had apparently evaporated slowly over time through the pickax hole and the crack at the feet, which the men decided accounted for the discolored earth in the holes.

The first thing the men saw was a packed layer of hay. After carefully removing a few handfuls, they found a body wrapped in a long linen burial sheet. More hay had been jammed between the corpse and the walls of the coffin, as though prepared for a long, bumpy journey. The packing was

John Paul Jones’s lead coffin, with, from left, an unidentified man; M. Géninet, a public works foreman; Paul Weiss, who led the excavation project; Arthur Bailly-Blanchard, second secretary at the US embassy; and ambassador Horace Porter.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress, Horace Porter Collection, Manuscript Division seen as a good sign, since Blackden’s letter to Jones’s sister had mentioned that the admiral’s body had been interred in such a way that it could be exhumed and shipped to the United States. Excitement built.

One of the men measured the body at five feet, seven inches long, the recorded height of Jones. They placed a half dozen lit candles on the dirt pile around the top of the coffin and carefully began unraveling the linen sheets from the head and upper torso of the body, revealing the face. “To our intense surprise, the body was marvelously well preserved, all the flesh remaining intact, very slightly shrunken, and of a grayish brown or tan color,” Porter said. The skin was pliable and moist, as was the linen wrap, and “the face presented quite a natural appearance” except for the nose. The cartilage at the tip had been bent sharply to the side, as though the nose had been crushed by the lid.

Porter and several of the other men had with them the Jones medallions Porter had ordered from the mint while he was conducting the records search. One was pulled out and placed next to the head. Both had the same broad forehead, similar-shaped brows, the same cheekbone structure, “prominently arched eye orbits,” and long, flowing hair. “Paul Jones!” some of the men shouted. Porter was ecstatic. “All those who were gathered about the coffin removed their hats, feeling that they were standing in the presence of the illustrious dead—the object of the long search.”

They had found John Paul Jones. But for now, it would be a secret.

Porter knew he needed more proof than his gut feeling and the well-preserved corpse’s resemblance to a face on a medal. Before the dig began, Porter had arranged with several Parisian-based experts in forensics to look over the body should it be found. One of them was Louis Capitan, a doctor and highly respected archeologist and anthropologist. Word was sent to the École d’Anthropologie, where Capitan worked and taught, to let him know a body had been found and that Porter thought it was likely Jones. Capitan replied via messenger that he was busy that day and Porter should reseal the coffin with plaster until he could get there. The linen was replaced around the head, the coffin lid set into a bead of plaster along the bottom lip, and the body sealed away.

Capitan arrived the next day and descended the ladder to the subterranean gallery. Despite his confidence that he had the right body, Porter was too meticulous to suspend the search. So workers scurried by, and the voices and sounds of digging echoed through the candle-lit tunnels. In fact, over the next week or so the men would find two more lead coffins, one with a nameplate identifying it as someone other than Jones, and the second without a name tag but holding a corpse well over six feet in height and clearly not that of the diminutive Jones. And with Porter trying to keep the discovery out of the newspapers for the time being, it was important that the daily gathering of the curious see the site consistently busy.

Capitan looked around the gallery. It was a close, ill-lit space with no room for a proper examination table. He decided conditions were too primitive and too busy for a proper examination. He conferred with Weiss and they decided to move the coffin to the École de Médecine. Capitan went first to the local police prefecture and explained the plan, asking for discretion, and then to the medical school, where he enlisted the aid and cooperation of the key figures there. That night, after the small crowd of curious Parisians had faded away, the coffin was carefully lifted to the surface, secretly loaded onto a cart, and hauled off to the medical school.

The next morning, an august gathering of medical experts surrounded the coffin, which had been placed on a glistening steel table. Capitan was there, as were Dr. Georges Papillault, an anthropologist who would study the anatomical details of the body; Dr. Georges Herve, who oversaw the work; Dr. A. Javal, a government physician; and J. Pray, a police official. Weiss and Porter were there too, along with Bailly-Blanchard, Gowdy, and several other men. In all, a dozen men would take part in or witness different aspects of the examination and autopsy, which would stretch over nearly a week.

The plaster seal was knocked loose and the lid carefully lifted away. The first issue was how to remove the corpse from its tight packing without risk of damage. They decided the safest approach would be to cut away the lead coffin. The metal was split at the head and the feet and then pulled apart, releasing the pressure and loosening the compacted hay. Then, very delicately, the body was picked up and moved to a dissecting table, where the linen was carefully unwrapped to reveal a man clad only in a long linen shirt decorated with plaits and ruffles. Exposure to the air two days earlier had already begun to affect it. Facial skin that had been moist and soft was now sunken and leathery, with the lips pulling back from the teeth in a grimace. Capitan noted that the body was so well preserved that the ligaments and muscles still kept the skeleton intact—they were able to move the body as a whole, without it falling apart, despite the more than 110 years that had elapsed since the man’s death.

The hands, feet, and legs were wrapped loosely in foil, a common burial practice in the late 1700s, when the Saint Louis cemetery was accepting bodies. The arms were folded across the chest, and the doctor straightened them to make it easier to examine the body. Porter reached out and gently picked up the right hand, as though to shake it in greeting. The knuckle joints bent easily, and the skin was soft to the touch. The face bore the stubble of a man who hadn’t shaved for a few days. The right eye was closed and the left slightly open, and lines had been creased into the skin from the linen wrap. The near-black hair had gone gray at the temples, and the bulk of it, some thirty inches long, was collected at the nape, rolled into a bun and wrapped in a linen cap with an odd bit of stitching that looked like the letter “J” from one view, but like the letter “P” when turned upside down.

They removed the linen shirt, along with the remnants of the foil, and positioned the corpse in a sitting position for a series of photographs. They then carefully examined the exterior of the body and found no scars or malformations. The skin was dark in tone, and the torso was flecked with small white crystals, part of what the doctors called the “autolytic process”—the conversion of enzymes after death but before the alcohol bath could begin to preserve the flesh.

Papillault carefully measured the body, now lying flat on the table. Consistent with the initial measurement at the cemetery site, he recorded it as five feet, seven inches long. Papillault then took a series of measurements of different elements of the corpse, creating an exhaustive collection of human topography. He focused particularly on the face, taking down its length and width, the dimension of the lips, and the chin. The plan was to match those measurements against the bust of Jones created by Jean Antoine Houdon when Jones was alive, a bust that Jones’s contemporaries had described as a near-perfect likeness. Paris’s Musée d’Ethnographie du Trocadéro had a copy, and Porter used his connections to gain permission to use it for comparison purposes.

It was not a perfect method, Papillault acknowledged. Allowances had to be made for artistic distortion, and a century-old corpse lacks the full-fleshed look of a living man modeling for his sculptor. “We had nothing to compare therewith but a skeleton covered with a tanned skin and shrunken tissues,” Papillault wrote later. Still, any sculptor of skill and repute would deliver a bust that resembled the subject in close details, he believed, or the sculptor wouldn’t have much in the way of commissions. Not perfect, no, but it would be good enough for their purposes. Especially since the bust and the corpse had an identical malformation of the earlobe—not the kind of tweak an artist would likely make for the sake of his art.

It took a couple of days for all of the measurements to be taken, checked, and double-checked. The corpse was photographed in several details, though by now the air had dried out the flesh until it looked like an ancient mummy. A hair sample was washed clean and its color noted as dark brown to black, which matched contemporary descriptions of Jones as being a dark-complexioned Scotsman, with dark hair and eyes. Capitan and Papillault also reviewed the paper trail that Porter and his deputies had amassed, including the contemporary descriptions of Jones’s burial. There was nothing in their first examination of the body to suggest another conclusion, Papillault reported. The body was Jones, he felt.

Yet they pressed on, seeking certitude.

The doctors went to work on the internal organs. Not wanting to disfigure the corpse in a way that would be visible, Capitan turned the body face down and then carefully cut deeply into the back of the torso. A small amount of discolored alcohol leaked out onto the table, and Capitan “was greatly astonished” to find the internal organs contracted but preserved, like a lab specimen. He began with the lungs, which held small whitish crystals, but also “small rounded masses, hard and at times calcified,” scars caused by pneumonia, from which Jones had suffered while in the service of Catherine the Great. The heart was “the color of dead leaves” yet remained soft and flexible, and had been healthy at the time of death. The spleen was larger than it should have been, but the rest of the major organs were healthy and unscarred. Except for the kidneys. They were “small, hard, and contracted,” much more so than would be accounted for by the general changes in the corpse after death. Capitan concluded they were diseased, affected by interstitial nephritis, and that the damage to the lungs suggested “a patient rather pronouncedly consumptive.” Capitan took small samples of each of the organs and set them aside, then carefully placed the organs back in the thoracic cavity and sewed the skin shut.

Another doctor, Cornil, reviewed the tissue samples, including a microscopic examination, and added to Capitan’s conclusions. The body on the table had suffered from pneumonia (there was no evidence of tuberculosis) and severe kidney failure. The afflictions accounted for the symptoms Jones had exhibited as he neared death—the difficulty breathing, the swelling of the lower limbs and abdomen. And the kidney disease was doubtless the cause of death.

Altogether, it was a persuasive array of evidence, some direct, some inferred. There was the research trail unearthed by Porter and his deputies. The details of Jones’s physical condition in his last days. The twentieth-century autopsy of the eighteenth-century corpse. All fed into the same conclusion. “Given this convergence of exceedingly numerous, very diversified, and always agreeing facts,” Capitan wrote, “it would be necessary to have a concurrence of circumstances absolutely exceptional and improbable in order that the corpse … be not that of Paul Jones.”

A week after the coffin had been found deep beneath Mme Crignier’s Parisian properties, Porter prepared a lengthy telegram to Washington. It was understated, and choppily written, but unequivocal. “My six years search for remains Paul Jones has resulted in success,” Porter began. He skated through the research that led him to the site, the details of the discovery of the coffin, its removal to the École de Médecine, the measurements, and the autopsy that “showed distinct proofs of disease of which the Admiral is known to have died.” Porter promised to mail copies of all the reports once they were completed, but felt compelled to wire Hay with the good news: he had found the right body. “Will have remains put in suitable casket and deposited in receiving vault of American Church till decision reached as to most appropriate means of transportation to America.”10

Porter received a congratulatory reply, and the exchange was remarkably muted given the time, effort, and expense that Porter, particularly, had put into the search. The elation came through in subtle ways. On the top of Porter’s initial telegram received at the State Department, someone scrawled an undated note: “Copies made for press!”