MUCH OF THE ALLURE of butterflies lies in the fact that they’re complicated creatures. Like ladybugs, ants, bees, and fleas, they undergo what is called complete metamorphosis. This means that they start out in one form and change into a completely different creature by the time they are fully developed.

We can’t think of many things that are as amazing as the life cycle of the butterfly. To progress from egg, to caterpillar, to chrysalis, to gorgeous winged creature, all in the course of a few weeks, is a rare and wonderful achievement. Here’s how it works.

Most female butterflies are able to mate as soon as they emerge from their chrysalis. Some males need a day or two before they are ready. On rare occasions, certain species of male butterflies will search for a female that is still inside her chrysalis, almost ready to emerge. The male peels open a small part of the chrysalis, mates with the female, and leaves behind some of his pheromone, a chemical substance that lets other males know that this female is already mated. But most butterflies find their mates during the course of the day as they fly around gardens, fields, parks, and wooded areas searching for sweet things to eat.

The butterfly egg, or ovum, is covered by a strong, protective membrane called the chorion. Tiny pores covering the egg surface allow the caterpillar embryo to breathe inside the egg. The egg may change color just before it is ready to hatch.

Gulf Fritillary egg on a vine tendril.

The egg usually hatches within a few days, depending on the weather and the time of year. The dark head of the caterpillar may be visible as it eats a hole in the egg so it can crawl out onto a leaf. Some caterpillars eat the rest of their eggshell before they start eating their host plant.

Butterflies have chemical receptors, something like our taste buds, on their feet, tongue, and antennae. They use them to smell the air, taste their food and their host plants, and pick up the scent of a mate. When a female is ready to lay eggs, she begins to search for appropriate host plants for the young caterpillars to eat. She finds these plants by sight and smell, landing on a plant of choice and scratching the leaf surface to “taste” it with her feet. Once she decides on a plant, she curves her abdomen downward to touch the plant surface and places an egg on a leaf, stem, flower, or seedpod. The butterfly’s body produces a special substance that glues the egg in place so it won’t wash off in the rain.

Butterflies lay their eggs in many different formations on a plant leaf: single eggs, groups of eggs, even eggs stacked on top of each another. Some are round and smooth like tiny pearls, while others look like barrels with ridges or dimpled golf balls. You’re not likely to find these eggs by accident; it usually takes a sharp eye to spot them. They may be placed on the underside of leaves, at the tip of a leaf, or inside blooming flowers. Some eggs are also very, very small. The eggs shown in our photos have been greatly magnified.

(TOP) Zebra Swallowtail egg on a pawpaw leaf.

(MIDDLE) Clouded Sulphur egg on a clover leaf.

(BOTTOM) Pipevine Swallowtail caterpillars eating their eggshells.

Never try to remove an egg from a leaf: It’s often glued on so strongly that the egg will tear apart rather than detach. If you want to take a closer look at an egg, look at it through a magnifying glass.

Question Mark eggs stacked on the underside of a hop vine leaf.

Pipevine Swallowtail eggs laid in a cluster on a pipevine leaf.

Painted Lady eggs on a hollyhock leaf.

Viceroy egg on the tip of a willow leaf.

Giant Swallowtail egg on the upper surface of a prickly ash leaf.

Common Buckeye eggs on the underside of a plantain leaf.

Butterflies spend the early part of their lives, the larval stage, as hungry caterpillars. They devour the leaves of their host plant so they can store up enough energy for their metamorphosis, the change from caterpillar to butterfly. For a couple of weeks on average, depending on the weather, they do nothing but eat. A caterpillar’s rate of growth is controlled by such factors as heat, humidity, and the overall quality and quantity of the host plant’s leaves. The caterpillar will grow faster if its host plant’s leaves are young and tender, and therefore easy to chew and digest.

Of course, the more a caterpillar eats, the faster it will grow, but a caterpillar’s skin can stretch only a small amount. Once it reaches its limit, stretch detectors in the joints between the body segments send signals to the brain to trigger the growth of a new, bigger skin underneath the old one. The old skin is no longer needed and must be shed. This process is called molting. Growth spurts between the molts are called instars. A caterpillar may molt up to five times, depending on its species, the weather conditions, and the availability of food. Caterpillars should never be disturbed during this process. They are extremely vulnerable to stress and injury, possibly fatal, at this stage.

There are several early indications that a caterpillar is ready to molt. It stops eating, it may sit very still for a long time, and it looks swollen, a bit like an overstuffed sausage.

A Zebra Swallowtail caterpillar is shown with the skin it has just shed.

This Eastern Black Swallowtail caterpillar is leaving its old skin behind.

To shed its old skin, the caterpillar first spins a small patch of silk as an anchoring point on a leaf or stem. Then it turns around and holds on to the silk with its rear claspers. The old head capsule pops off first. Next the caterpillar wiggles out of the old dry skin to reveal a new loose, moist skin. Still damp and pliable, the new skin stretches as the caterpillar takes in air. Some caterpillars eat their old skin at the end of the molting process. They may change color or physical appearance with each successive molt.

The coloration of some caterpillars allows them to avoid hungry predators: The greens and browns blend in with the environment or resemble bird droppings. Other caterpillars are brightly colored, as if to warn potential predators against eating them. For instance, the bright orange and black Monarch caterpillar absorbs toxins from milkweed plants, which can make vertebrates (animals with backbones), like birds, lizards, and mammals, very sick. These animals quickly learn to leave Monarch caterpillars alone. However, invertebrate predators like wasps and spiders are immune to these poisons and will happily eat Monarchs for lunch.

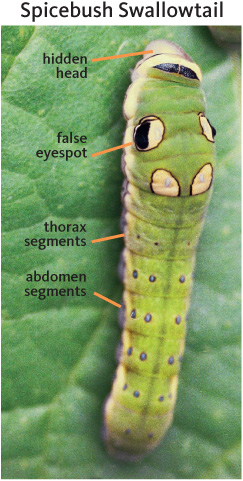

A caterpillar’s markings can also help protect it. Some caterpillars have false eyespots, patterns on the skin that look like large eyeballs. If approached, the caterpillar may rear up on its hind legs, perhaps attempting to look like a snake.

Swallowtail caterpillars have a special defense organ called an osmeterium. This is an orange or red forked gland that is hidden under the skin behind the head. When the caterpillar feels threatened, it can shoot out the gland like a snake tongue and touch the predator with it. If the sudden whiplash movement doesn’t spook the intruder, the foul-smelling substance that the gland secretes will offend even a human nose at close range.

(LEFT) This caterpillar is curled up and waiting for predators to leave. (MIDDLE) Sometimes looking like a snake is enough to deter a predator. (RIGHT) Swallowtail caterpillars have a bright orange or red gland, called the osmeterium, that they use to threaten attackers.

Bird dropping or Giant Swallowtail caterpillar?

The Monarch caterpillar is toxic to some predators.

Other caterpillars take a more passive approach: They curl up and drop to the ground if threatened. Once they feel safe enough, they return to the host plant.

Another tactic is the head-butt. If a caterpillar feels something brush against its skin, it may snap its head from side to side in an attempt to push away the intruder.

Most caterpillars are solitary eaters, but a few species dine together in groups. When they feel threatened, all the caterpillars may twitch at the same time, perhaps as a way to scare predators.

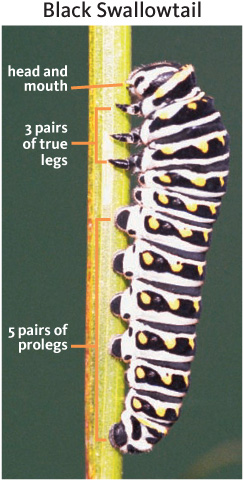

Caterpillars have several very tiny simple eyes that can detect light and movement. Their six true legs carry over to the adult butterfly stage. The prolegs are covered with tiny hair-like hooks for gripping.

Some caterpillars have large false eyespots that may fool predators into thinking they’re more of a threat than they are. The larger front segment also protects the head from attack.

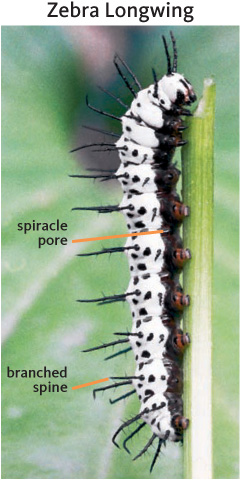

This caterpillar is covered in colorful knobs topped with black spikes. It looks scary but is actually harmless. Some moth caterpillars do have poisonous hairs and spines that can irritate your skin if you handle them.

Caterpillars take in air through small holes, called spiracles, on the sides of their body. Because these holes are so close to the ground, caterpillars can easily drown, even in a puddle.

Once a caterpillar has reached maturity, it begins to look for a good place to pupate, or enter the chrysalis phase. It stops eating and may empty the undigested contents of its gut. Sometimes it changes color. Generally, the caterpillar leaves its host plant and wanders away to find a safe place from which to hang. All sorts of locations may be suitable: A pile of wood offers good protection; the underside of a large leaf provides shelter from rain; a tree branch is an easy place to blend in. Sometimes the caterpillar spends several hours crawling around to find the perfect spot.

A silk thread secures this Eastern Black Swallowtail chrysalis in its customary upright position.

After the caterpillar has chosen a place, it begins to spin a patch of silk that will be the anchoring point for the chrysalis. The caterpillar has a gland called a spinneret below its mouth that produces silk. By moving its head back and forth, the caterpillar can weave a mat out of silk threads. Using special clasping hooks on its rear end, the caterpillar then backs up and grabs the silk patch and holds on tight. In fact, its life may depend on the strength of its grip. If the soon-to-be chrysalis can’t hang on through wind and rain, it will probably die when it hits the ground, bursting like a water balloon. If it survives the fall, a predator may eat it.

A Question Mark chrysalis blends into its brown surroundings.

We’ve discovered chrysalises hanging as low as a few inches from the ground on a plant stem and as high as six feet up on the side of a building. And when you have a garden full of host plants, you’re bound to find chrysalises in some strange places. Last summer we found one hanging from the underside of a rocking chair on Wayne’s deck. We couldn’t let anyone sit in it until the butterfly emerged. We’ve found chrysalises hanging from deck rails and garden statues, as well as on sliding glass patio doors. We’re now in the habit of checking everywhere for these surprise packages.

A Black Swallowtail chrysalis sheds its caterpillar skin.

After the caterpillar gets a good grip, it may hang upside down, as Monarchs do, or spin a silk thread and use it as a harness to support itself upright, as swallowtails do. Up to now, juvenile hormone has kept the insect in the caterpillar stage through each molt. Now that it is fully grown, production of this hormone has stopped, and the caterpillar sheds its skin for the last time, to reveal a chrysalis. The old skin splits first at the head, and the pupa wiggles and squirms its way out. When the skin has peeled all the way down to the rear end, the pupa must twitch violently to break the small ligament attached to the skin. Then the skin falls away like a stretched-out old sock.

Once the chrysalis dries and hardens a bit, it gains some protection from the weather and small predators. Its dull coloration, usually shades of green or brown, helps it blend in among leaves and twigs. If this phase of its life cycle occurs during the warm summer months, the butterfly should be fully developed and ready for eclosion, or emergence from its chrysalis, in about two weeks. If the insect enters its chrysalis phase during the cooler months of autumn, then it may wait out the winter by going into diapause, hibernating until warmer spring weather arrives. Sometimes butterflies that emerge in the spring are smaller than the ones that emerge during the summer months.

This Spicebush Swallowtail caterpillar changes from bright green to yellow-orange just before it enters the chrysalis phase.

During the chrysalis phase, the caterpillar liquefies inside the chrysalis and reorganizes, almost magically transforming into a butterfly. Even after decades of research, all the details of this metamorphosis are not completely understood.

Variegated Fritillary

Viceroy

Monarch

Question Mark

Pipevine Swallowtail

When the butterfly reaches maturity, a special hormone triggers a set of events that allow the adult insect to break free from its chrysalis shell. Entomologists believe the butterfly takes in air to swell itself up, causing the chrysalis to split open along specific weakened seams. In some species the chrysalis becomes transparent at this time, and you can actually see the pattern of the wings through the membrane.

A newly formed Monarch chrysalis dangles like a piece of gold-rimmed jewelry.

Using its new long legs, the butterfly pulls itself out of the chrysalis and clings to the empty shell so that its crumpled wings can hang down freely. It begins to pump its wings slowly up and down, and constricts its body to force the yellowish insect blood, called hemolymph, into the wing veins so they can expand and open up to their full size.

As the veins fill with fluid, the wings stretch out and start to dry. The butterfly has only about an hour to extend its wings fully. If they aren’t extended within this time period, they will harden in their folded position and be permanently deformed. It is vital that the butterfly not be handled or disturbed at this time. Without the ability to fly properly, the butterfly cannot live for very long.

(TOP) The chrysalis splits at the seams and the Silvery Checkerspot pulls itself out. (MIDDLE) The wet wings are crumpled and must stretch out before they dry. (BOTTOM) The tongue is in two pieces and must be “zipped” together before it will function.

During this time, the butterfly must also fuse the two halves of its tongue, called the proboscis. By using microscopic muscles, the butterfly interlocks the halves to form a tube. It will use the tube to suck the nectar and other fluids it needs to survive. If a butterfly is unable to fuse its tongue, it will starve.

After a short time, the newly emerged butterfly excretes a fluid called meconium, the liquid waste left over from metamorphosis. Once its wings are completely dry and its tongue is in working order, the butterfly takes to the air.

Monarch.

Zebra Swallowtail.

A butterfly emerges from its chrysalis as a fully grown adult. You may see different sizes of the same species of butterfly, but often the difference is due to factors such as weather and food supply that affected the growing caterpillar. Sometimes the males and females of a species are naturally different sizes; usually the egg-carrying female is larger.

Most summertime butterflies have a very short life span: about a week or two. During that time the butterflies focus mainly on searching for food and finding a mate. They rely heavily on their keen senses of sight, smell, and taste to locate all the things they need to survive and reproduce.

The scales on the wings of this Gulf Fritillary are colored by pigments. With its wings wide open, the butterfly absorbs heat from the early-morning sun to dry off last night’s dew.

We can tell that this Eastern Black Swallowtail is a male because of the row of large, light-colored spots across the middle of the wings. Females have smaller spots, and more blue on the lower wings.

Red-spotted Purple … male or female? To the human eye, the male and female of a butterfly species can be difficult to tell apart.

Butterflies have large eyes that can see many colors, including those in the ultraviolet range that humans can’t see. If we use special lighting, we’re able to observe that many flowers almost glow with ultraviolet patterns. To the butterflies, these flowers must look like brightly lit runways! Butterflies can also detect movement better than we can — that’s why it can be so difficult to sneak up on them. If a male butterfly sees something fly by that looks like a possible mate, he’ll move quickly to investigate. If it turns out to be a rival suitor, he may chase him out of the area to prevent any competition. If it’s a female, he’ll pursue her, performing his best aerial acrobatics.

With the chemical receptors on their antennae, butterflies can detect odors in the air. They can locate food, potential mates, and perhaps other things that we don’t even know about. When a butterfly lands on a flower, a mushy fruit, or a patch of tree sap, it can taste the food with its tongue and its feet. The length of a butterfly’s tongue varies by species. Some are capable of feeding from long tubular flowers; those with a shorter tongue must sip from flatter-faced blooms.

You’re not likely to see many active butterflies when the temperature is below 50°F/10°C. Like all other insects, butterflies are cold-blooded and must bask in the sun on cool days to warm up their flight muscles before they are able to fly. We often see butterflies sunbathing on our stepping-stones.

The thousands of dusty scales that cover a butterfly’s wings and body absorb heat from the sun. The butterfly can make its wings tremble and shiver to help speed up the warming process. It knows exactly how to orient its wings to the sun so it can absorb heat more quickly. This is important, as a sitting butterfly is vulnerable to attack.

Some butterflies seem to need more heat than others do. We have observed Mourning Cloak and Question Mark butterflies flying around on very chilly mornings, hours before other species even attempt to fly.

The Question Mark has scales along its wing edges that reflect ultraviolet light.

The scales covering the wings and body also give a butterfly its pretty colors. Some scales are colored by pigments; others are iridescent, appearing shiny or metallic because of the way light hits them. A few are transparent. The scales are loosely attached to the wings and overlap each other, rubbing off easily when touched. This prevents things from sticking to the wings and may make the wings more difficult for a predator to grasp.

Wing scale colors allow butterflies to recognize each other. Many scales reflect ultraviolet light and act as markers, so species look different from one another. Males and females of the same species also look different from each other. Our eyes can only see these subtle patterns if we view a butterfly under special lighting.

In just the right light, the Pipevine Swallowtail shows off its shiny metallic blue wing scales.

Most summertime butterflies live only a week or two. Within that short time they urgently seek out a mate so they can reproduce. Because they also need to find food, take shelter from bad weather, and avoid hungry predators, locating a mate can be a daunting challenge.

Each species of butterfly produces its own pheromones (chemicals that stimulate mating behavior). Potential mates can smell pheromones from a distance, which is a more reliable way of finding each other than just depending on a chance meeting.

Once a male and female have sighted each other, some species begin elaborate courtship “dances” involving a lot of chasing and aerial stunts. The male shows off his ultraviolet-reflective wings and the female decides if he’s worthy of her attention. On a few occasions we’ve seen a butterfly get his signals crossed and attempt to mate with a female of a different species. This usually results in the male getting a quick wing slap from the female. Sometimes butterflies will fight if more than one male approaches the same female.

These Pipevine Swallowtails have perched on the seed head of a coneflower to maneuver into mating position.

Some male butterflies are so eager to mate that they seek newly emerged females that are still drying their wings. Since the female can’t fly yet, the male’s success is guaranteed. This strategy saves the male the trouble of impressing a female with his fancy flying by chasing after her, and it allows him to spend his extra time and energy looking for another available mate.

Male butterflies employ various techniques to scout for a potential mate. When hilltopping, the male lingers at the top of a hill or a tall stand of trees, where he can get a bird’s-eye view of the area. Females that need to find a mate instinctively visit landmarks that can be seen from a distance.

Other males may try perching. This means they pick out a sunny spot in an area where lots of butterflies congregate and then just sit and wait. When something of interest passes by, they dart out to investigate. They may continue this behavior for as long as several hours or until they’ve found a mate, unless they give up and move on.

The male Giant Swallowtail uses special claspers on the tip of his abdomen to hold the female’s abdomen against his own.

Male butterflies often gather in groups at muddy areas, especially those next to streams, to sip dissolved salts and minerals. This behavior, called puddling, may provide the extra nutrients males need for mating.

Another mate-finding technique is patrolling. The male finds a dividing line where one type of habitat meets another, and he actually patrols the area. A stream cutting through woods or a stand of trees at the edge of an open field is a good example of this type of transitional area. Sometimes the male will also patrol areas where host plants grow, in the hope of finding a female that has just emerged from her chrysalis.

IT’S A CHILLY SPRING MORNING when the butterfly awakens. Droplets of dew glisten like diamonds in the early light as they cling to closed wings, thin legs, and delicate antennae. As the sun rises and a breeze begins to stir, the moisture slowly evaporates. The butterfly opens its wings and turns to absorb the heat from the sun’s rays. After its flight muscles are warm enough, the butterfly flutters away from its evening roost to explore its surroundings.

Food is the first priority. Tempting flowers dance in fields and wild places. The hungry butterfly finds a patch of coneflowers and lands to sample the sugary treat. Its long tongue uncurls like a streamer and carefully explores each blossom. Each flower offers up just a smidgen of nectar, so the butterfly must sample many more to satisfy its appetite.

After a morning of successfully dodging predators and drinking lots of nectar, the butterfly is ready to look for a mate. A male butterfly often lingers at the edge of a field and along the top of a hill, looking for the newly emerged females that fly through his territory. Then real chemistry comes into play: The male’s pheromones attract females, and if a female finds the male suitable, she allows the male to mate with her.

The male has special claspers on the tip of his abdomen that hold the female’s abdomen flush with his own so he can deliver a packet of sperm to her. Normally, the butterflies must perch on something in order to maneuver into the end-to-end mating position. They remain connected for several minutes or longer.

Now the pregnant female needs to find a host plant for her eggs. She seeks plants that will provide enough food for all her offspring. Ideally, she’ll lay just a few eggs on each plant, so the soon-to-be caterpillars will not have to compete with each other for their daily meals.

Laying all her eggs (and there may be hundreds) can take several days. As the sunlight begins to fade into dusk and the temperature drops, she must find a place to roost in safety during the night so she can start all over the next day. Sadly, once she has outwitted predators and struggled through wind and rain to deposit her precious eggs, the butterfly doesn’t live for very much longer. But with a little luck, the next generation of beautiful butterflies will soon follow.

Red Admiral on a coneflower.

A Monarch wet with morning dew.