When we were growing up we spent many weekend mornings with our mother on hiking trails. Her love of trees, flowers, and critters was definitely contagious. We would roll out of bed at the crack of dawn so we could be the first ones to the park and have the trails all to ourselves. We would often compete with each other to see who could identify the most trees and flowers and spot a box turtle or a chipmunk.

Our interest in insects began when we discovered dead butterflies on the grilles of trucks in parking lots. Many times their wings were in very good condition, flattened against the radiator. We would carefully peel them off and take them home to add to our collection. After several years we had examples of nearly every kind of butterfly that was common to our part of the country. We still have these specimens pressed in frames to remind us of our first sparks of childhood interest.

After we grew up and became homeowners close to each other in Kentucky, we both decided to fill our yards with flowers. At first we gardened with no real plan or purpose in mind. We each learned the hard way that some plants are very invasive and others are too finicky to grow in our Kentucky clay. So, after much trial and error — and endless trips to nurseries — we decided to garden strictly for the butterflies we loved. Our backyards are now overflowing with every kind of caterpillar host plant and nectar-producing flower we can get our bug-loving hands on. We compete to see who can grow the widest variety of host plants and nectar flowers and take the best photographs of visiting butterflies.

Eastern Black Swallowtail chrysalis.

We’ve used as many of those pictures as possible in this book, not only for your enjoyment, but also to help you identify a specific butterfly during any stage of its development. We took most of them in our own backyards; the others were taken at local parks.

When we first started to entice butterflies to our flower gardens, we relied heavily on resources that listed specific host plants and nectar flowers. We weren’t experienced enough to know what these plants actually looked like just from reading their names, which were often in Latin. Because we remember our early frustrations, our book provides actual pictures of the host and nectar plants that we’ve used successfully in our own gardens.

Every day is a new adventure for us: checking plants for eggs and caterpillars, sneaking up on butterflies to photograph them, and excitedly phoning each other when we spot a new species visiting our yards. As you use this book, we hope our enthusiasm rubs off on you. We’re sure that once you experience the joy and wonders of the butterfly world, you’ll be hooked just as we were so many years ago.

Eastern Black Swallowtail on purple butterfly bush.

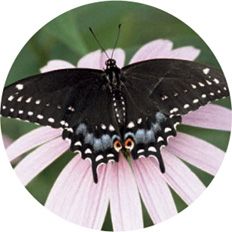

Eastern Black Swallowtail on coneflower.

Note: Throughout this book, we have recommended a wide variety of plants that attract, feed, and shelter the featured bugs. Most are native spieces. Nonnative spieces that may be invasive are marked with an asterix(*). Invasives vary from region to region. Please consult your local extension service, botanical garden, nursery, or conservation organization for a list of plants that may be invasive in your area. Also ask for a list of native plants that are suitable for your area.