Epilogue

After Nayiniyappa’s son Guruvappa died in 1724, French officials in Pondichéry considered doing away entirely with the post of chief commercial broker. The French governor at the time, Joseph Beauvollier de Courchant, worried about appointing another powerful local to the job: “Chevalier Guruvappa having died, and Tiruvangadan [Nayiniyappa’s brother-in-law] being the kind of man to take on too much authority if we were to make him courtier, we announced to the Blacks that from now on there will be no modeliar [chief broker].”1

But Beauvollier de Courchant encountered opposition from other high-ranking French officials in Pondichéry, who insisted that they simply could not operate without an Indian courtier. The governor himself also came to the realization that he could not govern the colony without the help of a Tamil courtier. He needed a broker, he wrote in a letter to Paris, to warn him in advance of all the rumblings and doings in the town.2 He ultimately selected Pedro, the native Christian who had filled the post after Nayiniyappa’s arrest in 1716 and before Guruvappa’s ascension in 1722. As he wrote, “We could not choose anyone but Pedro, beloved by the Blacks, and who would never take to himself more authority than that which we had given him.”3

The governor’s justification for ruling out Tiruvangadan—that he was “the kind of man to take on too much authority”—and approving Pedro as the kind of man who would do no such thing pointed to the central problem the French encountered when employing professional intermediaries. A broker could not succeed without authority. But how much authority was too much? What actions or powers would tip the balance, changing an intermediary from a trusted helpmeet to a threat? No clear answer could be given. Even the most valued intermediaries raised the specter of danger, as Nayiniyappa’s downfall reveals. But the aftermath of the Nayiniyappa scandal reshaped Pondichéry in the 1720s, as the reluctance to appoint an intermediary intimates. French officials had reason for their reluctance to make another Indian—especially one who had a knack for procuring power—a central actor in the colony.

More than half a century after Nayiniyappa’s arrest, the issues that animated the Nayiniyappa Affair and its details still informed and motivated French colonial policy. In 1776, exactly sixty years after Nayiniyappa’s arrest, a letter signed by Louis XV provided instructions for the newly appointed governor of Pondichéry, Guillaume de Bellecombe. At the time, French officials in the colony were fighting about the appointment of a new chief commercial broker, with different factions in the colony making the case for different local men. The king’s orders from Versailles settled the matter by decreeing that one of Nayiniyappa’s descendants be appointed to the post. “His ancestors have always filled the position since 1715 [the actual date was 1708], and one of them came to France and was decorated with the Order of St. Michel for the important services he provided to the nation.”4 The new appointee, the royal order hopefully continued, would surely prove to be as devoted to the French as his illustrious ancestors were. The Nayiniyappa Affair was unfinished business, as colonial and metropolitan French officials continued to struggle over the best way to implement their rule in India while relying on local intermediaries.

Distributed and delegated authority, I have argued, was the hallmark of the early decades of French presence in India. The simultaneous codependence and antagonism between the French projects of commerce and conversion engendered a crisis of authority in Pondichéry. As a result of the inherently partial, fractured, fragmented potential of early projects of expansion, colonial authority was widely and unexpectedly dispersed. That is, colonial power and agency were, partly because of their mediated nature, distributed power and agency. This allowed Tamil intermediaries employed by the French—commercial brokers and religious interpreters—to rise to positions of prominence and power, much to the discomfort of their French employers. In Pondichéry’s early days, sovereignty was bifurcated because of the clash of religious and commercial agendas. The reliance on local intermediaries was in part a result of this bifurcation; as missionaries and traders were in an ongoing and voluble state of conflict about the kind of rule they wished to implement in India, both groups needed to rely on local go-betweens to help them advance the agenda to which they subscribed. The reliance on go-betweens also entailed efforts to limit and circumscribe this very dependence.

Even as historians have shown that French absolutism was more propaganda than reality in Europe, they have failed to examine the limits of French claims to power in the colonial context.5 The tensions between commerce and conversion in Pondichéry were the site-specific example of a broader feature of early modern European empires, in which attempts to imagine or present a unified vision of authority, one that enacted the agenda of the metropolitan state, encountered the friction of practice. In Pondichéry and in the offices of the company in Paris, officials wanted to strengthen their authority in the town—but this authority was not the same ideological construct as hegemonic sovereignty, familiar from later colonial examples. In religious, commercial, linguistic, and legal realms, French rule in India did not, as a general rule, demand a monogamous relation to the authority of the Compagnie des Indes. For native residents of Pondichéry, political identity and allegiance could be multiple, such that there was no need to consider themselves unambiguously and exclusively subjects of the French king. French deployment of political, religious, and legal authority was a delicate balancing act.

At the time of Nayiniyappa’s arrest, France’s entangled imperial efforts were straining at the seams, ridden with contradictory ideologies and methods of pursuing success. Trader-officials’ and missionaries’ visions of French rule in India were not always compatible with one another, and interactions with local professional intermediaries allowed and at times required the articulation of incommensurate agendas. By revealing the repeated conflicts among and between agents of the French state, the Compagnie des Indes, and religious authorities, this book has shown how early imperial formations could never fully achieve hegemonic authority, fracturing instead into factions and foes. These conflicts were articulated through and with colonial intermediaries.

The intersection of interests of traders, missionaries, and go-betweens prior to and following Nayiniyappa’s arrest demonstrates not only the constant and ongoing conflicts between colonizers and colonized—a widely analyzed phenomenon—but also the less commented-upon tensions and factionalism between various branches of the French overseas project. The Nayiniyappa Affair therefore highlights the fact that in French India, the lines between colonizer and colonized, patron and client, could not be quite so sharply drawn. Nayiniyappa’s position as chef des malabars and chief commercial broker to the Compagnie des Indes allows a privileged view into the roles colonial intermediaries in Pondichéry filled. As a professional intermediary par excellence, Nayiniyappa reflects the ways in which the intermediary position was Janus-faced, simultaneously facing home and away, toward past and future, the familiar and the new. Different colonial agents held varying expectations of Nayiniyappa and intermediaries like him, and the global and sustained interest that the Nayiniyappa Affair generated was the result of French ambivalence in both commercial and religious quarters about dependence on such intermediaries.

The Nayiniyappa Affair was a pivotal event for French India in that contemporaries understood it as both momentous and transformative.6 Nayiniyappa’s arrest disrupted the established order and called into question the practice of distributed authority. As an event, the affair was both revelatory of social structures and transformative of these same structures. In the context of colonial South Asia in the eighteenth century, in which European rule was a shaky proposition at best, scandals and trials provided privileged opportunities for hashing out the meaning and shape of sovereignty in both its Indian and its European guises.7 The Nayiniyappa controversy provided the involved actors an opportunity to consider and argue for different visions of France and its empire.

By the end of the affair, the colony was becoming a place in which colonial power exerted itself in more familiar forms—with a greater reliance on French language and French (or at least Christian) personnel. In the mid-eighteenth century, and especially under the ambitious French governor Dupleix, the nature of the French presence in India changed. This period saw much more aggressive, military attempts to bring about French territorial expansion in the subcontinent.8 But in the first half of the eighteenth century, the French in India were clients as much as patrons. This was true in relation to Indian rulers, from regional courts and principalities all the way up to the Mughals. But this was also the case in their relationships with their local intermediaries, relations that were always symbiotic and reciprocal, in which the balance of influence and reliance occasionally shifted, such that the French could be patrons one day, clients the next. Working relations between French administrators and the moneyed commercial brokers in Pondichéry did not always allow for clear hierarchical distinctions, and affiliation with the French company and even with French missionaries did not necessarily entail subordination. French trader-administrators, cognizant of their profound dependence on local markets and patterns of familial obligation and patronage, largely refrained from attempts to restructure or displace these patterns, as would become common in later colonial projects. The French did seek to circumscribe the power and centrality of Tamil players in the governance of the colony in the second half of the eighteenth century. But the transformation was never complete. When the Christian chief broker Pedro died in 1746, the French authorities replaced him with Ananda Ranga Pillai, Nayiniyappa’s relative, who was not a Christian. The lure of the services a well-connected local man could provide proved stronger than the preference for a Christian .

In constructing an account of the colony from the details of the Nayiniyappa Affair, I have told an imperial history in a local register. The affair might seem too minor a prism. These are, after all, the trials and tribulations of one man. Arlette Farge and Jacques Revel have suggested that historians studying events that might appear at first glance too minor or atypical should play with scale, simultaneously paying close attention to the minutiae of the archive that “resist generalization and typology and are perhaps ultimately incomprehensible,” as well as to the systemic and structural frameworks in which such events take place and from which they both derive meaning and imbue with new signification.9 The temporally concise framework of the Nayiniyappa Affair contains an elaborate, expansive, and complicated webbing of affinities, commitments, animosities, rivalries, and ideologies of French traders, missionaries, and their Tamil intermediaries. By describing the various assemblages and clusters and the seemingly contradictory and disparate explanations for the conviction of Nayiniyappa and his exoneration, I have sought to provide a view of the whole. The history of empire revealed through the affair shows that accounts of the largest of large-scale processes, such as global networks of commerce and conversion, can still make room for the human-sized experiences of loyalty, fear, vengeance, and love.

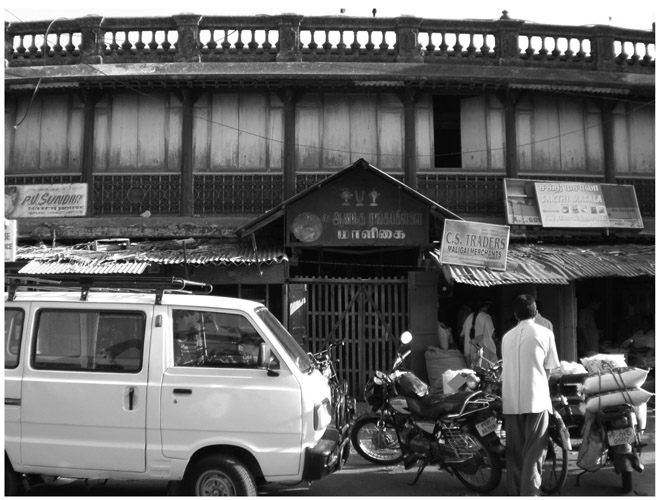

In the summer of 2008, a direct descendant of Ananda Ranga Pillai, and therefore an indirect descendant of Nayiniyappa himself, gave me a tour of his property.10 Exactly three hundred years after Nayiniyappa was first appointed to a position of prominence in Pondichéry, the carefully guarded yet darkened mansion serves as a potent reminder of the family’s former power and the memorializing of that power by subsequent generations. A businessman, Ananda Ranga Ravichandran lives with his family at the center of Pondichéry’s “Tamil Town,” adjacent to the city’s central market, where Nayiniyappa was flogged. His house is a simple, well-maintained structure, no different from the others on the street. But a door leading from the kitchen opens into a small backyard, and this opens a portal into a family’s glorious past. There was an ancestral home, the now-dilapidated but still striking mansion that Ananda Ranga Pillai built for his family in the 1730s (figure 4). Approaching the house from the parallel street, I could readily see vestiges of the house’s former glory, though the clutter of the market street muted the effect.

FIGURE 4. The sign, in Tamil, identifies the building as “Ananda Ranga Pillai’s mansion,” viewed here from the central market of Puducherry, as the town is now called. Photograph by author.

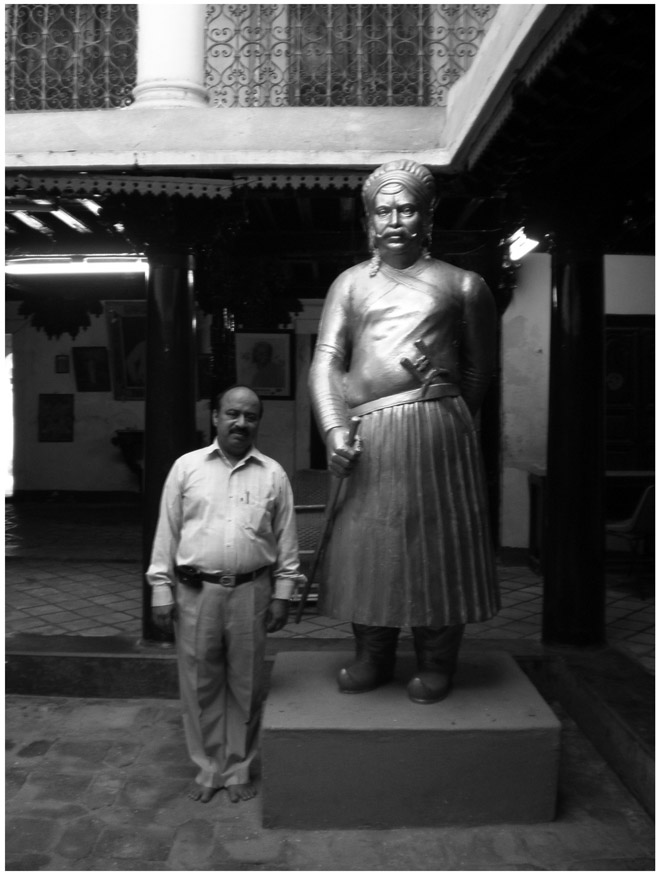

When the British razed Pondichéry in 1761 as Ananda Ranga Ravichandran’s famous ancestor lay dying, few of the colony’s mansions survived. The situation of Ananda Ranga Pillai’s house, farther from the coast’s so-called White Town, saved it. The mansion’s architecture is a clear mix of Tamil and French styles, with heavily carved wooden pillars in the Tamil style surrounding the ground floor’s main space and white columns supporting the second floor veranda, in the French manner. When I asked to take a picture of a golden statue of Ananda Ranga Pillai, Ravichandran proudly stood next to it, his body as close as possible to the pedestal, head tilted toward his illustrious ancestor (figure 5).

Behind the statue, on a back wall next to photographs of Ravichandran’s parents, hangs an eighteenth-century portrait of Ananda Ranga Pillai, painted by an unknown artist. A lavishly illustrated volume about the history of the Compagnie des Indes includes a reproduction of the portrait, which is partially discernible in figure 5.11 The caption in the volume notes the source merely as a “private collection,” obscuring the spatial and familial specificity of the portrait’s survival from the eighteenth century.

FIGURE 5. A statue of Ananda Ranga Pillai, chief broker to the Compagnie des Indes in the mid-eighteenth century and Nayiniyappa’s nephew. Standing next to him is his descendant Ananda Ranga Ravichandran. Photograph by author.

Although the mansion stands empty most of the time, it serves as a memorial of the influence members of Nayiniyappa’s family once wielded in the colony. Pondichéry’s French Institute once held a conference devoted to the diaries of Ananda Ranga Pillai in it, and the local government recently recognized it as a heritage site. Ravichandran said he was hoping to receive funds for the mansion’s restoration so that he could convert it into a boutique hotel. Pondichéry’s robust tourism industry nostalgically evokes an imagined French colonial past, one carefully scrubbed of the violence and inequities of colonial reality.12

As I walked through the mansion, with its imposing golden statue presiding over empty rooms, it was easy to imagine it as a repository of sorts, an archive of material sources for a biography of colonial power, its unexpected forms, and ultimately its decline. In maintaining the mansion and keeping the memory of Ananda Ranga Pillai alive for Pondichéry’s present and future, the family was making a claim for its own historical significance. Just a short walk away, the “Rue Nainiappa Poullé” attests to that significance. The cracked street sign is made of blue tin, of the same kind used for Parisian street signs (figure 6). With its Tamil name rendered Francophone, its Parisian-inspired tin weathered by the local heat, the sign is a tangible remnant of the distributed authority that created the Nayiniyappa Affair.

FIGURE 6. In Puducherry today, one can walk along Rue Nainiappa Poullé. Photograph by author.