EVERY SKETCH TELLS A STORY

Because technological limits prevented Civil War–era photographers from capturing subjects in motion, sketch artists provided the most dramatic images of many memorable incidents. London-born Alfred R. Waud stood out among a talented group whose work found a large audience in the loyal states and included, among many others, Winslow Homer; Waud’s brother, William; and Edwin Forbes. The relative absence of major illustrated weeklies in the Confederacy (the Southern Illustrated News paled in comparison to Harper’s Weekly or Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper), among other factors, made for a much less dynamic market for sketch artists in the Rebel states. Another Englishman, named Frank Vizetelly, sent in 1861 by the Illustrated London News to cover the American conflict from the Union side, decided, in mid-1862, to change his base to the Confederacy. During the remainder of the conflict, he produced a large body of firsthand illustrative evidence relating to the southern nation at war.

Alfred Waud’s sketches, many of which were published as engravings in Harper’s Weekly, include some of the best-known Civil War images. His rendering of Union soldiers carrying comrades away from menacing fires during the second day of the battle of the Wilderness brilliantly conveys the horror of combat. One soldiers crawls toward safety, another raises his arm in hopes of securing help, and two of the four principals, with a wounded man slung in a blanket held by two muskets, look over their shoulders toward the encroaching flames. Equally effective is Waud’s spare drawing of the moment when Confederate infantry overran a Union battery at Gaines’s Mill on June 27, 1862. Attackers emerge from dark woods in the background, approaching open ground littered with dead and dying horses, while artillery shells burst to the top right and rear. The Confederates appear as an indistinct mass, with only a few figures well defined, yet the drawing pulses with a sense of movement and power.

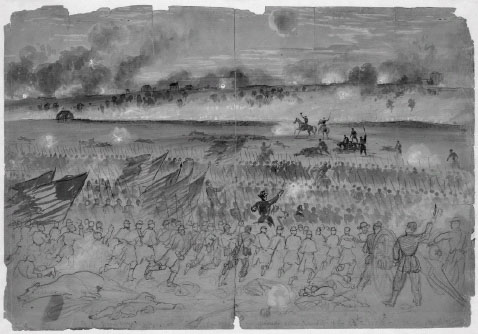

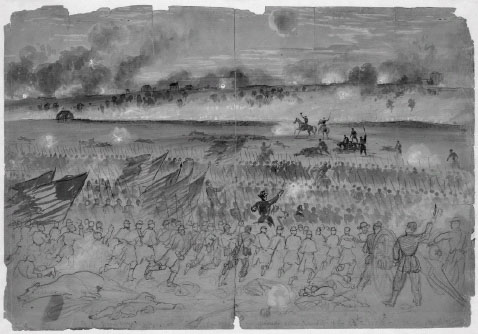

Two memorable sketches of the battle of Fredericksburg display Waud’s artistic gifts. For the charge of Andrew A. Humphreys’s division against Confederates situated along the base of Marye’s Heights on the afternoon of December 13, 1862, Waud left figures in the main body of the division indistinct while highlighting Humphreys, astride his horse and waving his hat, against a cloud of smoke from the Rebel infantry line behind the famous stone wall. An engraving of the sketch appeared in Harper’s Weekly on January 10, 1863, and, though engraver Henry L. Stephens did an admirable job, a comparison of sketch and engraving shows how published versions often lost much of the drama and immediacy of the originals. The second sketch, frequently reproduced over succeeding decades, depicts soldiers of the Fiftieth New York Engineers building the upper pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock River under Confederate fire from William Barksdale’s Mississippians on December 11. The men’s vulnerability and purpose seem equally evident in Waud’s gripping treatment.

“Genl. Humphreys charging at the head of his division after sunset of the 13th Dec.” Waud’s drawing captures the drama of Humphreys’s assault, with the general at the front of his division waving his hat and smoke from Confederate artillery and infantry fire blanketing Marye’s Heights. (Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-19522.)

Away from the battlefield, Waud sketched many prominent figures and famous episodes of the war. On the afternoon of April 9, 1865, he waited in the yard of Wilmer McLean’s house at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. Inside the substantial red brick structure, Ulysses S. Grant and Robert E. Lee labored over details regarding the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee appeared on the front porch between 3:30 and 4:00 p.m., called for an orderly to bring him his horse, and within a few minutes had mounted Traveller. Waud watched the scene intently. Of the many famous episodes he had witnessed, none exceeded in importance or interest this final scene of the war in Virginia. Waud rapidly captured the action as Lee departed. Two figures dominated his study—a grim-visaged Lee on Traveller and, trailing slightly behind, Colonel Charles Marshall of the general’s staff. Waud’s eyewitness sketch would grace numerous books about the war, and a more polished version appeared as an engraving in the Century Company’s Battles and Leaders of the Civil War. Because of Waud’s presence at Appomattox, generations of readers formed a visual impression of the most important Confederate shortly after he signed a document that essentially ended the four-year conflict.

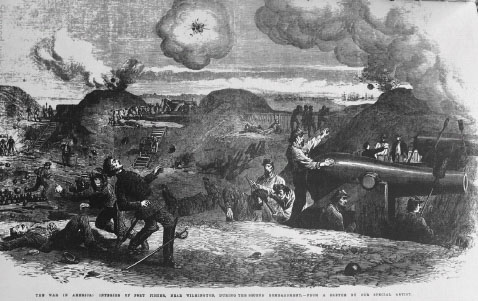

Although Vizetelly’s sketches match Waud’s in neither artistic quality nor historical impact, they provide invaluable glimpses of the war. Some deal with combat—perhaps most famously, a sketch of the heavy Federal bombardment of Fort Fisher on January 13, 1865. Amid shell bursts above and inside the fort, Confederate gunners work their guns. Vizetelly’s notes on the sketch describe “an officer + two men killed by fragments of shell” in the left foreground and “a few dead” in the middle of the fort. “The exposed position of the men,” he wrote of the day’s action, in the Illustrated London News, “with shells of the largest size falling and exploding in the midst of them, is terribly apparent in our illustration.” Present to witness the attack on Fort Wagner on July 18, 1863, Vizetelly prepared a drawing and described the burial of Union dead in language that aligns well with the final scene in the film Glory: “In the ditch they lay piled, negroes and whites, four and five deep on each other.”65

“The War in America: Interior of Fort Fisher, Near Wilmington, during the Second Bombardment,” by Frank Vizetelly. (Illustrated London News, March 18, 1865, p. 249.)

Vizetelly also sketched disparate scenes unrelated to battles. These include a vignette of Jeb Stuart and some of his staff and subordinates in the autumn of 1862; the prisoner of war camp on Belle Isle in the James River at Richmond; white refugees in the woods near Vicksburg in 1863 (“The country for forty miles round Vicksburg is covered with small encampments of women and children who have been driven from their homes by predatory bands of Northern soldiers,” he wrote); and a Federal shell exploding in the streets of Charleston in 1863. Vizetelly accompanied Jefferson Davis’s small party as it made its way southward after the fall of Richmond in 1865, departing just two days before Union pursuers captured the Confederate president on May 10 at Irwinville, Georgia. Several sketches show the group in flight, including one of Davis “signing acts of government by the roadside” and another of him “bidding farewell to his escort two days before his capture.”66

For a fuller appreciation of Waud and Vizetelly, readers should consult Frederic E. Ray’s Alfred R. Waud: Civil War Artist (1974) and W. Stanley Hoole’s Vizetelly Covers the Confederacy (1957). Both offer an array of the artists’ work, though the quality of the reproductions in Hoole’s volume is less than ideal.