A few Americans who managed to make it by boat from the Philippines to Australia in 1942 described Philippine guerrillas they had known as ragged, starved, almost defenseless, and reduced to something close to banditry just to stay alive.1 Donald Blackburn paints a vivid picture of Robert Arnold, long missing and presumed dead, when he walked into Blackburn’s headquarters in north Luzon in the spring of 1943. Arnold was covered with tropical ulcers, many of them infected and filled with pus. Embittered against all guerrilla organizations, even the Volckmann-Blackburn unit to which he had just come, because he thought them ineffectual, Arnold said he had lived for the past year on a diet of rats and corn, and that he knew other guerrillas who were cannibals as well as bandits. Blackburn adds that after a week or so of plentiful food, a good bed, and some medical treatment Arnold changed his mind, came to appreciate the abilities of his hosts, and even wanted to join their organization.2 Yay Panlilio says that some men in Marking’s guerrillas succumbed to a combination of tension and boredom and began to do such mad things as play Russian roulette, at which several shot themselves.3 She adds that the combination of privation, danger, and quarrelling among leaders eroded morale seriously. Men grumbled sourly that they were wasting their lives, that the Japanese harmed the Filipino people far more than they (the guerrillas) were able to harm the Japanese, and that the Americans would never come back. Many simply could not endure it, she said; they despaired and went back to the towns.4

That such conditions existed in some other irregular outfits, I have no doubt, and we had our share of such problems, too, perhaps the worst being gut-wrenching decisions that had to be made about the disposition of prisoners, real or suspected spies, and disobedient subordinates—as will be related in bloody detail later in this narrative. Every one of us also knew that each day might be his last. Even so, neither Al Hendrickson and I together, nor either of us separately, ever had any morale problems of the magnitude described by others.

We moved around a lot, seldom staying in one place for more than a week. Contrary to what some might assume, though, these sojourns did not consist of marching up and down main roads seeking pitched battles with the Japanese. Most of our days were humdrum, spent in simple, obvious ways: hiding, sleeping, gathering and evaluating information, planning, nursing each other, rustling food, recruiting new followers, looking for opportunities to accumulate arms, and occasionally circulating propaganda or committing some act of sabotage.5 Of such activities much the most important was collecting intelligence. Merely ambushing half a dozen Japanese now and then could not have much effect on the outcome of the war.

Still, as time passed it became increasingly evident that we were discommoding our foes. As early as March 19, 1943, Radio Tokyo had made reference to Philippine guerrilla activity, an indication that the Japanese already regarded it as a problem of some consequence. By the end of 1943 Japanese soldiers no longer wandered about alone. Now every Japanese outpost contained at least four men, and they dug trenches under the buildings in which they lived. One night we stopped close to a Nipponese outpost and listened to those inside praying to their emperor to bolster their spirits. Clearly life was a lot less agreeable for them than it had been.

Meanwhile the villagers who hid us went about their customary activities as their ancestors had done for generations. The women squatted on the banks of streams and beat the dirt out of family clothing with wooden paddles, in the process often chewing betel nut or indulging in the strange practice of smoking cigarettes with the lighted ends inside their mouths. Now and then they would take a break and undertake a collective assault on the head lice that are commonplace in the Philippines. They would sit in a line, one behind the other like a row of monkeys, and each would pick the lice and nits from the head of the woman in front of her. I never did figure out how the last one in line was accommodated. It seemed to me that a circle would have been a more logical configuration.

During the rainy season sudden fierce downpours were common, but nobody seemed to mind, or even notice it much. The men, usually barefooted, dressed in shorts and, armed with bolos in wooden scabbards attached to their belts, went about their business as usual. Women would pack whatever they had to sell and walk off to market quite as readily during a cloudburst as on a sunny day. Funerals were frequent, rain or shine, and were always joyous occasions; never sad. Wine and sweet foods would be shared, as at a party. When the deceased was being taken to his final resting place, his cortege was always preceded by a brass band if anyone could find or assemble one.

Still, we lived under constant strain because we never knew when the Japanese might spring a surprise attack and capture us. The danger seemed especially great at night. I never reached the point where I could take it all in stride, and I don’t think Al Hendrickson did either. It seemed that every Filipino farmer had at least two dogs and that every one of them for miles around would bark at the slightest provocation: We all became light sleepers; and Al, who had exceptionally keen hearing, would awaken almost every night, nudge me, and ask me if I had heard “that”—whether “that” happened to be the millionth dog barking, the sound of a truck on a distant road, or something else. I would routinely remind him that we had three rings of guards all around us and tell him to go back to sleep; but I was so edgy that I seldom followed my own advice. Scores of times I got out of bed and made a nocturnal tour of the guards to make sure all of them were awake and alert.

Months later when I was in Pangasinan province, I established a simple and seemingly foolproof method of recognizing friends and foiling enemies in the dark. A guard, when challenging someone, would say, “Halt!” and then follow up with a number, such as “two.” The person challenged would then reply some other number, “three,” “four,” or whatever number comprised the code for that night. This safeguarded us against Japanese, who were adept at repeating English words flung at them as challenges but would have no way of knowing what different word or number was expected on a given occasion. Al preferred a different but comparably simple system: using words from Filipino dialects, which very few Japenese knew, as passwords.

Whatever the system, a person never felt entirely safe; never sure that something unforeseen would not happen. An episode with a particularly bloody ending has always stuck in my memory. It took place near San Nicolas in eastern Pangasinan. Here two Americans, one of them bearing the memorable name of Jewel French, were being protected, they supposed, by a Filipino bodyguard. One night he picked up an automatic rifle, riddled them as they slept, kicked their bodies into the Agno River, and went over to the Japanese. The guerrillas never captured the man, but they settled accounts with him nonetheless. A few weeks later he was with a small company of Japanese who fell into an ambush.6

Many of our persistent difficulties with our bands of irregulars were rooted in the elementary fact that our control over them was only tenuous. To be sure, all our men recognized Al and myself as their leaders and they would obey us when we were with them, but at any given time only a few of them would be armed and actually with us. Routine guerrilla operations, moreover, were usually carried out by underlings to whom we gave only general directions. Often subordinates would embark on enterprises of their own choosing without bothering to notify superiors. Likewise, the superiors did not always want to know everything their lieutenants were doing.

Many times, too, operations were undertaken not for any real military purpose but simply to avenge atrocities against civilains. Panlilio records that on one occasion Marking became so enraged at some particularly fiendish Japanese cruelty that he marched their whole outfit over the Sierra Madre Mountains to fight the Japanese, saying that he was determined to kill as many of the enemy as he could even if the whole Filipino nation perished in the process. Fortunately, his rage subsided before he was able to do anything suicidal.7

I have read that Filipinos, whether guerrillas or ordinary civilians, were often reluctant to fight. Maybe they were in some places or at some times, but my experience with them was quite the reverse. Many times individual Filipino civilians killed Japanese on their own, without reference to guerrillas at all. Many a Filipino, guerrilla or otherwise, came to me with tears in his eyes begging for a gun so he could kill a Japanese who had committed atrocities against his family. Much as I sympathized with such people, and great as my delight would have been to accommodate them, my problem was always to quiet them down and persuade them that it was essential to avoid trouble that would activate the enemy’s military police, who might then catch me and inflict some hideous mass punishment on the helpless Filipino civilians who had harbored me. But sometimes we attacked Japanese patrols or small installations for no reason other than to keep up the morale of our men, to allow them to let off steam.8

Many a raid, too, was undertaken mostly to get supplies. The Japanese occupation forces and their creation, the new Philippine Constabulary, were outfitted heavily with what had been taken from Americans after the fall of Bataan and Corregidor. Guerrillas would then raid Japanese installations, kill the defenders, and take back the arms, ammunition, food, gas masks, shoes, money, and wrist watches sequestered earlier by their foes. Japanese corpses were even fished up from rivers to get such commodities. How precarious life often was for everyone in the wartime Philippines can be indicated by a number of disparate incidents, some funny, some grim, some both. One night Al Hendrickson and I were on the move when we came to a broad, deep ditch bridged by a single large bamboo pole with a frail hand rail attached. As mentioned earlier, Al had exceptional hearing. He tested the bamboo bridge and jumped back, asking me if I had heard it crack. I said I hadn’t, and assured him that it was strong enough to bear an elephant. Al was still skeptical, but at my urging he started to cross it. He edged out cautiously to the middle when, with a crack like a pistol shot, the bamboo broke. Al plummeted into the water several feet below. Fortunately, the water wasn’t deep, but the mud beneath it was both deep and stinking. As Al strugged to climb out of the mess, he let loose a torrent of profanity. Most of it was directed at me for having urged him on in the first place, and now for laughing at his predicament. He was doubly infuriated when I refused to walk close to him because of the stench of the mud.

Al was still simmering from this mishap when we came to an exceptionally large ricefield. Clomping around the near edge of the paddy was an old man carrying a lamp that consisted of a lighted wick in a Vaseline jar full of coconut oil. He said he was trying to catch frogs. Al, who knew the local dialect, directed him to lead us along the dikes to our destination across the field. Since the dikes in and around this ricefield went in every direction, it was hardly surprising that after much walking in complete darkness we found ourselves back at our starting place. Nevertheless, we were dismayed; and Al was still burning from having fallen into the stinking mud earlier. Now he stormed at the old Filipino as though he would explode. He drew his .45 and cursed the old man in English until his vocabulary was exhausted. Then he repeated the cussing in Finnish, then in Spanish, then in the old man’s dialect, and finished by telling the frog hunter he was going to be shot because he was a Japanese spy. I’m sure the poor fellow fully expected to be killed before Al cooled off and we moved on.

As if we didn’t have enough routine troubles, the Huks began to undertake nuisance raids against us late in 1943. In an effort to put an end to this, Hendrickson made arrangements for one more conference with Huk leaders, this time in a small village near La Paz in Tarlac province. Of course, I can see now, four decades later, that it was always useless to try to make common cause with the Huks about anything since we, quite as much as the Japanese, were obstacles to their ultimate aims, but if we still tried to deal fruitfully with communists periodically it can at least be pleaded that we were no more gullible than Allied governments who strove to treat amicably with the USSR in the same years.

To get to the meeting place we first had to ride in a calesa along a well-travelled road. Then we transferred to a railroad handcar propelled by a long pole, and then to horses. We finished the trip on foot. This was typical of the precautions necessary when moving in no man’s land where everyone was suspect. We knew well enough the risk we were taking in meeting the Huks on their home ground, and when we finally arrived I was decidedly uneasy. About Al’s state of mind I am less certain. He told me afterward that he knew that the Huk leader had stashed a couple of his men in a shack behind us where they could shoot us if they wished, adding that he had countered this maneuver by posting a BAR (Browning Automatic Rifle) man and a rifleman of ours behind them. Apparently he found this setup reassuring since he spoke to the Huks bluntly; though once, during a breather, he remarked to me half-ruefully that he wondered if we would get out of the place alive. Maybe the Huks did not mind Al’s hard words unduly or simply did not have orders to kill us; anyway, they let us depart unmolested. The effort itself was a waste of time, as we should have expected after they had shot Harry McKenzie.

Proverbially, we had escaped the frying pan only to fall into the fire. As soon as we got back to our area, we found that the Japanese army and military police had decided to combine and make an effort to capture as many guerrillas as possible, Al and me in particular. To this end they devised a new tactic: to send a handful of soldiers, for some reason called “snipers,” to slip up to individual Filipino houses at night, where they would listen to conversations. On the basis of whatever information they gleaned, the Japanese would then undertake guerrilla-type countermeasures. This development produced panic not only among civilians but among some of our own men as well.

Since the new Japense stratagem was reported to involve two thousand men, Al and I decided it was time to depart. We left Tarlac and moved off northward into Pangasinan province. Here we settled for a short time near the town of Bayambang on the Agno River in an area known locally as the “fishponds” because fish were raised there commercially. There was so much water everywhere that we had to move at night by boat, as though we were in Venice. One night we passed through a narrow canal where fish nets had to be removed so we could get by. In the process the fish became so excited they leaped out of the water in all directions, some of them into our boat. The boats themselves were distressingly primitive: mere hollowed logs so overloaded with men and equipment that when I gripped the sides of mine my fingers were in the water. Needless to say, nobody made any unnecessary movements. I was too scared even to ask the depth of the water.

One evening we stopped at a large hacienda. Here were beds with mattresses, a luxury we had not seen for two years. Unhappily, our anticipated joy in getting to sleep in a real bed proved illusory. After trying it a few hours we awoke with our bodies sore from the unaccustomed softness and spent the rest of the night on the floor.

Unquestionably, the best thing that happened to me at this stage of the war, the spring of 1944, was that I selected a new bodyguard, Gregorio S. Agaton. Greg was young, clean-cut, alert, fearless and absolutely loyal. He saved my life several times, the first time not long after he joined me. The occasion arose amid resolution of a persistent problem that has vexed genuine guerrillas for generations: how to deal with “armies” that profess to be guerrillas but are actually mere gangs of bandits.9

Shortly before we fled north into Pangasinan, reports began to come in from distressed people in western Tarlac that a certain Filipino freebooter there was trying to organize a “guerrilla” force of this sort and to exact contributions from civilians. Since nobody in his outfit was known to have fired a shot at a Japanese and since he had made no contact with our headquarters, it was hard to imagine anything constructive coming from his operations. So we sent out an arrest order for him. Three days later he was delivered to us. According to reports, he had made a number of statements highly critical of our organization, so we exercised utmost caution when he was called before us. Greg and Little Joe, Al’s bodyguard, and several more of our men trailed the arrested man closely as he walked into our room. The fellow was wearing a native shirt that hung loosely outside his trousers. During our first verbal exchange he made a sudden motion with his right hand toward his right hip pocket. Al and I immediately drew our .45s. He returned his hand to the front. We then told him he was about to die.

Several of our own men at once interceded for the suspect, saying that he now realized how things stood and would not do anything contrary to our wishes. The suspect added his own profuse assurances that this was indeed the case. So, after a warning, we let him go. After he had departed, I noticed Greg and some of our boys grouped together examining something. I stepped closer to see what it was. It was a strange looking .38-caliber revolver. I asked Greg where it had come from. He said he had pulled it from the back of the belt of the man we had just released, precisely at the time when Al and I drew our .45s. Thus, we had not misinterpreted his intention at all, and had it not been for Greg’s alertness one or both of us might have died right then.

The recurrence of episodes like this had much to do with the reluctance of guerrillas to take prisoners and to their general tendency to shoot first and ask questions afterward. They also intensified the constant tensions of guerrilla life. Vernon Fassoth recalls once being hidden in a gloomy, stinking jungle, famished, frightened, utterly spent, and enmeshed in clinging vines. Suddenly he could endure it no longer. Overwhelmed with rage and frustration, he seized his .45 and aimlessly defied fate by shooting wildly at the vines even though he knew the Japanese might hear the shots. Vernon also once saw a big, brawny man gradually sink into exhaustion from carrying a load too heavy for his smaller buddies. After hours of backbreaking toil the giant suddenly stopped and hurled the hated bundle into a rice paddy even though it contained food and other commodities sorely needed by his whole party.10

I sometimes responded to similar pressures by similar recklessness, though more often in a way that reflected elation or fatalism than frustration or depression. Al said he liked me because I was usually good-natured, talkative, and ready for anything, where many of the American guerrillas were grim and humorless. In fact, Filipinos who knew us looked upon both Al and me as something like playboys since we would sometimes go to dances in rural barrios and dance with the local girls. I would jitterbug, Al would dance an Irish jig, and his girlfriend Lee would sing, all to the delight of the local people. We knew the risks involved, but I, at least, simply did not care because I did not expect to live through the war anyway.

Once I did something that a psychiatrist would probably ascribe to temporary insanity. It was December 1943, and we appeared to be well settled in Eastern Pangasinan. December 11 was my twenty-fourth birthday. For the occasion we located a cameraman with good equipment and had him take some pictures of our headquarters staff. I really knew better than to do this, and if one of my subordinates had done it I would have punished him. Why I did it I cannot explain convincingly even to myself. Anyway, I did take the precaution of having only one print made of each picture, and had it delivered to me. The negatives were hidden by the photographer. It soon became evident that Murphy’s Law applied in the Philippines just as it does everywhere else. We heard that the photographer had been picked up by the Japanese. We sweated blood. Everyone in the picture would be wanted immediately. Most of those concerned rushed into hiding. I ordered a search made at once for the negatives. Luckily they were found, hidden under the grass roof of a house.

Another instance involved defective judgment, too, but at least the blunder was less egregious. This time we were holed up in a village near Bayambang in southern Pangasinan in December 1943, when a Filipino from a neighboring barrio came to us one day and said he had a radio receiver powered by an automobile battery. He asked us if we wanted to hear a news broadcast. He assured us that he did not mean Tokyo Rose, the notorious Japanese propagandist, but an American broadcast. Since we hadn’t heard a radio report in two years, we assented. Then came the bad news. The receiver was on the opposite side of a town occupied by the enemy. Probably we would have been discreet and stayed where we were, had our informant not added that the town contained an ice plant where we could get ice cream, something we had not enjoyed since the war started. That clinched it. We followed our man, crossed a river in a canoe, then climbed into a calesa for a ride around the outskirts of the town. As we rolled along, our guide informed us casually that we would soon have to pass a Japanese sentry. For a moment I was paralyzed with fear, and I would guess that Al was too, but neither of us wanted to lose face in front of the other so we rolled down the buggy’s side curtains, pulled out our .45s, and laid them across our laps. For insurance I prayed that we would not be challenged. If we were, the first thing that would happen would be that we would leave a dead Japanese solider lying in the road, but of course the gunfire would be followed by an alarm and there was no obvious place for us to try to escape. Luckily for all concerned, we rolled serenely past the guard, who gave us a perfunctory wave.

The radio was hidden in a haystack near a large mango tree, which our guide climbed to secure the antenna. We sat down to listen to the news and music. I particularly recall hearing Bing Crosby sing, of all songs for our locale, “White Christmas.” No doubt this would have buoyed up the spirits of many, but it had the opposite effect on Al and me. For me every Christmas since 1939 had seemed more depressing than the last. To hear this song brought back memories of my father, mother, sisters, and friends back home, whom I had trained myself for many months not to think about. I now thought of how good wheat bread and ice cream would taste; of what a pleasure it would be to smoke a Camel instead of uncured Philippine tobacco cut into strips and rolled into cigars so strong that for months I got a cheap drunk every time I smoked one. It was all a dismal reminder of how lonely, forlorn, and precarious our present existence was. Now, if there is one thing a guerrilla must battle constantly it is depression and despair.11 This experience was not helpful.

Sometimes combatting depression took strange forms. I recall once when Hendrickson was feeling particularly down that I tried to cheer him up by telling him that I did not expect to survive the war either but that we ought to die fighting, shot in the front, not shot in the back while running away or beheaded by the Japanese in some prison. He never told me whether he found this rumination consoling. Be that as it may, after we had listened to the radio we rode back unmolested past the same guard. Though he never knew it, his inattention to duty saved his life.

Men and women who lived in Japanese prison camps have related much more about the depression attending such an existence than I will ever know. Still, it was apparent to me how depressed many prisoners became during the war. For instance, some of the American prisoners at Cabanatuan, which was not far from where we operated, were assigned to drive trucks to nearby towns to secure vegetables and rice to feed those in the camp. Many times I had individual guerrillas approach these drivers and urge them to escape. They always got the same reply: “Not now, Joe, maybe later.” It surely was not that they had no desire to escape, since all prison camp literature indicates that most prisoners think about escape a great deal. I eventually learned, too, that the prisoners in Cabanatuan knew guerrillas were active in the vicinity; indeed, that they sometime heard gun battles between guerrillas and Japanese, and saw dead Japanese soldiers being hauled back to the camp in trucks. The truth seems to be that there is a vast gulf between thinking idly about escape, or even planning an escape, and actually trying to get away, especially when one is weak from disease and undernourishment, and when he knows that if he is captured not only will he be killed but that quite possibly as many as ten of his fellow prisoners will also be killed in reprisal. I have often wondered how many of the drivers whom our men tried unsuccessfully to lure away survived the war. Some died in the camps themselves; others were killed inadvertently by American bombs and submarine torpedoes when the Japanese tried to transfer them in unmarked ships to Japan; still others died in Japan itself.

Soon after our narrow escape when listening to the clandestine radio, Japanese activity in the area increased, so Al and I vacated the environs of Bayambang and headed off northeastward across Pangasinan. As we travelled, we met several heavily armed units belonging to Lapham’s command. Each escorted us to the next one within the area. Along the way I traded my old M-1 rifle for another and got myself into a predicament which illustrates some of the constant problems we had with weapons. Whenever possible, we tested rifles before having to depend on them in combat. Greg took this new one into the usual underground covered pit and fired it. The ejector tore away part of the shell rim, leaving the shell casing in the chamber. I looked at the gun and discovered that the chamber was so badly pitted that I would have to use a ramrod every time I fired the piece in order to knock out the old casing. I didn’t have a ramrod, and several hours of laborious filing to try to smooth the chamber proved fruitless.

Eventually the problem was solved in a way not prescribed in any manual. A few days later we met a Filipino Constabularyman who had been armed by the Japanese with an M-1. I proposed to him that we trade rifles, or parts of them. He said he couldn’t because his Japanese masters would notice the different serial number. I wasn’t worried about his problems, so I offered him an alternative: trade rifles or join our guerrillas on the spot. He traded.

One morning when we had proceeded some thirty or forty miles northeastward from Bayambang into the vicinity of San Manuel in eastern Pangasinan, we ran into a nest of Japanese. We sighted some to the north across a ricefield and so turned south to a village where we promptly encountered more. Runners told us there were still more to the west, so we did the only thing possible: we moved east until we reached the Agno River, a large stream that flows out of the central Luzon mountains southwestard across Pangasinan and then turns north and runs into Lingayen Gulf. Here our prospects looked dark indeed: surrounded on three sides by the enemy and with the far side of the river an unknown quantity. For all we knew, the Japanese might have set an ambush there. No matter. To cross was our only chance.

Many times before this Al and I had crossed streams by a means that will surely seem odd to Americans: we had been “bobbed” over by Filipinos. The method was simplicity itself. Though we were bigger than Filipinos, each of us would climb onto the back of one, the man would leap into the stream, hit bottom, leap upward, gulp in air when his head bobbed out of the water, spring off the bottom again, and so on. Each motion carried “bobber” and rider farther downstream, but both gradually got across.

This time no such luxurious mode of transit was available to us, for the rainy season had arrived and the Agno had become a raging torrent. Some Filipino civilians saved the day by bringing us some large gourds wrapped with vines. We put our sidearms and ammunition inside, tied our rifles across the top, grasped the vines with one hand, and paddled energetically with the other. Everyone got across satisfactorily save a Filipino spy whom we had unwisely kept with us. As soon as he got into the water, he swam downstream as fast as possible, returned to the same side where we had started, and took off across the countryside. We didn’t dare shoot at him because the noise would alert the Japanese, who were too close to us already. Now he was free again; free, as we subsequently learned, to go back to his home, a place fortified with a stone wall topped with broken glass and surrounded by floodlights.

Luckily for us, the Japanese disliked big, fast streams, perhaps this one especially since on earlier occasions several of them had drowned in the Agno. Now they came up to the river, looked over the situation, and decided to camp on the shore opposite us. This gave us a sorely needed breather—and a chance to get ahead of them once more. The respite was brief. Soon they made their way across, picked up our trail, and pursued us relentlessly. For five days and nights Al and I and about fifty guerrillas moved steadily eastward across southern Pangasinan with the enemy never more than a village behind us and sometimes separated from us only by a ricefield.

Still, much as they hated guerrillas, and much as they would have exulted to use all of us for bayonet practice, the Japanese were a calculating lot. If they were in unfamiliar territory, or knew local irregulars had them outnumbered, they usually discovered compelling reasons to stay in their encampments. In our case, they did not dare to close with us, both because we were more numerous and because they would have had to advance toward us across open fields in daylight while we were protected by groves of trees around villages. So they spent their days torturing civilians and pondering what to try when night fell.

It has been observed many times that if habitually destitute people happen to get a little unexpected money, often they will not do the “sensible” thing and purchase necessities with it but will instead spend it “foolishly” on some luxury—at least in the opinion of people who are not destitute. Whatever quirk of human psychology is responsible for such conduct cropped up among us on the fifth day of our flight from our pursuers. We were in a village close to the mountains east of the town of Umingan, collecting provisions. Next day we were going up into the foothills. The Japanese were one village away, making their own preparations to follow us. In these circumstances, when one would suppose that every one of us would have been serious and vigilant in the highest degree, Al bet me that Lee could field-strip an M-1 as fast as I could. Like a hungry bass who has heard a frog jump into the water, I rose to the bait and bet she couldn’t beat me even if I was blindfolded. Anyone could guess what happened next. Just as we got our rifles dismantled, the enemy began to advance toward us. Al shoved Lee aside, I tore off my blindfold, and he and I began feverishly to reassemble the rifles. Alas! One part became interchanged and neither gun would work! So we had to tear them apart and put them back together again since by now both of us had long since come to subscribe to what the infantryman had told me during the Battle of the Points, that a soldier must become wedded to his rifle.

A tense competition in self-control between ourselves and the Japanese followed. We moved out of the east side of the village and down a creek bed while the enemy poured into the village from the west side. Not a shot was fired; on the Japanese side, presumably, because they were not looking for a gun battle in which we would be hidden and they would be in the open; on our side because we did not want to give our foes an extra pretext to maltreat the village people who had helped us. Besides, we hoped next day to be in a place where we would have all the advantages in a battle and there would be no civilians about to complicate matters.

That night we slipped into a farmhouse where the natives from the last village had been preparing rice for us, but almost immediately had to move on when the enemy continued to advance. With the heartening bravery I witnessed so many times in the Philippines, the villagers, even with our common enemy in their midst, tried to deliver the food to us, in the dark, in our new location. Some Japanese snipers, uncharacteristically moving about after dark, jumped them and one villager was bayoneted. The others escaped, though without the food, and ran to our new hideout to warn us.

There followed a scramble that might have been lifted from an old Abbott and Costello movie. Both Al and I were asleep in a pitch-dark room. He ordinarily took off his pants when retiring, and had done so now. I habitually slept in my clothing but had unbuckled my sidearms and had leaned my rifle against the wall. When we got the alarm, both Al and I immediately appreciated the urgency of the situation, but we were still half-asleep when we sprang into action. I rushed to the wall to get my rifle but couldn’t find it because I had gone to the wrong wall. I whispered, “Where is my rifle?” then finally found it, and only afterward remembered that I also had to find my sidearms and put them on. Al, equally confused, stormed around in the dark shouting, “Where the hell are my pants?”

We half-climbed, half-fell out of the house down a bamboo ladder, exchanged quick whispers with the men who had alerted us, and prepared to move out when Al complained that his pants, which he had finally located, didn’t feel right. There was a good reason: he had put them on backwards. Despite our hazardous circumstances, I couldn’t help laughing, adding that now the Japs would shoot him in the back for sure. Al responded profanely, but we got out of there so fast he didn’t bother to change his reversed trousers.

We spent the rest of the night up in the foothills, but after surveying the countryside with binoculars the next morning we decided to move back down into the flatlands. At once we ran headlong into the enemy. All day long we skirmished with the Japanese but could gain no advantage. By evening we had to decide what to do next.

During the American Revolution, 165 years before, Francis Marion, the “Swamp Fox,” would have his men scatter in every direction after an engagement, thereby making enemy pursuit impossible, following which they would eventually meet at some prearranged place.12 Though I knew nothing about Marion’s tactics at that time, we had long used a similar stratagem. When we were in some danger and felt compelled to break up, we would select three possible meeting places, number them in order of their attractiveness, and then try to meet at one of them. Nearly always at least one place would be available and reasonably safe. This time the Japanese probably expected us to go back into the foothills again after dark, but instead we slipped through their lines back into the central rice plains from whence we had come.

We did this for three reasons. The most basic was that we thought the Japanese would not expect it. We were also short of food, and there would be little back in the mountains. Finally, we were worn down physically, and traversing Philippine mountain trails is particularly difficult for Westerners. In most parts of the world mountain roads or trails follow terrain that offers the least resistance; they usually angle upward along mountainsides, frequently by means of switchbacks. Not so in the Philippines. The first time I saw little Igorot tribesmen shoulder heavy loads and lope, not walk, along paths that went straight up mountainsides, I was dumbfounded. Of course, the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, but many Igorots develop enlarged hearts from heeding this axiom of geometry while we Occidentals could not travel rapidly in this way at all. Laboriously we trekked back across Pangasinan, along the way we had come, and went back into Tarlac province. A major change in my fortunes took place soon after.

As noted earlier, most guerrilla existence was an amalgam of danger, privation, and occasional boredom, interspersed with life’s ordinary problems and vexations. It also bore another aspect which has heretofore received only passing notice in this narrative. That side was grim, cruel, bloody, and degrading, but given the character and deeds of our enemies, unavoidable.

We Americans are notoriously poor judges of the psychology of other peoples and maladroit in our dealings with them. In the 1940s the Japanese were incomparably worse. Had they treated the Filipinos with kindness and generosity from the first day of the war, many of the latter would have accepted their fate, and many who remained loyal to America initially would have gradually gone over to the conquerors as months of Japanese occupation stretched into years. But the Japanese army was filled with hubris as a result of its quick and easy conquests, and Japanese field commanders usually acted harshly in an effort to scare civilians into cooperation. Japanese military administration, by contrast, gradually began to urge leniency in an effort to win the sympathy of civilians. The latter might have worked had it been instituted in December 1941, but by 1943 there had been far too many crimes committed by Japanese against Filipinos for such a policy to have any chance of success. If military administration secured the release of some prisoners, few evidenced any gratitude. Most soon showed up with guerrillas, or worked with them secretly. As soon as guerrillas became strong enough to provide an alternative focus for the loyalty of Filipino civilians, they put pressure on local officials appointed by the Japanese and neutralized them as Japanese instruments. Moreover, the struggles of guerrillas against the Japanese soon passed into Filipino folklore and strengthened the Pro-American sentiments of most civilians. The Japanese were never able to counter this effectively. As the famous nineteenth-century German chancellor Bismarck used to say, it is the imponderables that are the most important factors in human affairs.13

By the time I became a guerrilla, it had been learned long before by hard experience that if the enemy secured rosters of guerrillas they would confiscate the property of these men, and then seize their families and torture them. It is impossible to conceive a more effective tool to use against Filipinos, whose primary allegiance has always been to their families rather than to the nation or state. The Japanese would also do such things as enter a village, herd everyone into the marketplace, then lead out an informer completely cloaked from head to foot save for slits for his eyes, and compel every person in the village to pass before him. When the informer lifted an arm, the individual then passing would be seized by the Japanese and put aside. When all had passed before the collaborator, and those who had aided guerrillas or otherwise shown themselves to be anti-Japanese had been pointed out, the hapless victims were marched to a field, made to dig a pit for their own burial, and then bayoneted to death.14 Another ploy of the Japanese was to send out their own agents, who would say they were collecting money and supplies for the guerrillas. Those who contributed would then be seized and tortured or killed, or both.15 If a guerrilla was captured, the Japanese would often torture him to death, stretching out the process over many days. The enemy would sometimes even behead the corpses of guerrillas.16

The techniques employed by the Japanese to extract information from prisoners and civilians, or to punish their enemies, were revolting, but some of them must be described if the reader is to comprehend the unbridled ferocity with which guerrillas often responded to such deeds. A favorite Japanese punishment was to “flood” a victim; that is, force water into his stomach until it was three times normal size, then pound the victim with their fists as if he were a punching bag, or jump on him, thus forcing liquids to squirt out all his body orifices.17 Another favorite treatment of theirs was to tie a victim’s thumbs behind his back, toss the rope over a beam, and pull him up until his feet were off the floor. In an effort to get information the Japanese once crucified a Filipino boy for three days and then killed him with a sabre.18 At the war crimes trial of General Yamashita, a Filipina woman testified that two Japanese soldiers had held her while two others tried to cut out her husband’s tongue because he would not give them information, which he did not have, about local authorities.19

Simply to punish persons who had crossed them in some way the Japanese did such things as pull out all the victim’s teeth, toenails, and fingernails,20 or chain him to a slab of galvanized iron in the hot sun, to be slowly fried alive.21 Merely to terrorize civilians the Japanese would sometimes send out a patrol at dawn to gather underneath a Filipino house-on-stilts. Many Filipino families then slept all together on the floor. At a signal the Japanese soldiers would thrust their bayonets violently up through the thin bamboo flooring, impaling men, women, and children indiscriminately, until blood would drip down through the floor onto the assailants. They they would burn down the house.22

Ideally, guerrillas should have captured the Japanese responsible for such atrocities and executed them. In practice, this was impossible since the Japanese ordinarily fought to the death rather than surrender, even on those comparatively rare occasions when there was some chance to take prisoners. What was usually done as second best was to ferret out Japanese spies and collaborators among Filipino civilians, and punish them.

Now many writers have charged, after the event, that all guerrillas were unreasonably hard on anyone who collaborated with the Japanese.23 Their point of view is understandable, but many times we had to take drastic action on not much more than suspicion, or simply disband. We had organized guerrilla units in the first place to make life difficult for the Japanese and to collect information for Allied headquarters in Australia. We could not do either one without consistent, widespread, predictable civilian support. We could not get that support unless we made it safe for civilians to cooperate with us. Thus, our foremost immediate problem was always to pursue informers relentlessly and exterminate them. This not only made life safer for civilians sympathetic to us; it also caused fence sitters to gravitate to our side. The way we dealt with spies and suspected spies does not make pleasant reading, nor does it give rise to happy memories even forty years later but, like so much in war, it was the result of excruciating quandaries that armchair moralists never have to face.

There is no question that some guerrillas, both Filipinos and American, exceeded all norms of reason and humanity in their relentless pursuit of informers and subsequent treatment of them. Most Filipinos are mild, peaceful people, but if aroused or enraged they can become vindictive and capable of frightful cruelties. Illif David Richardson relates an instance on Leyte that illustrates the point. Some Filipino guerrillas there caught some of their countrymen collaborating with the Japanese, so they minced their bodies and floated the pieces downstream into Filipino villages. The number of collaborators dropped off sharply.24 An even more sickening case on the same island involved a luckless ten-year-old Filipino boy whom the Japanese had taught to become a sharpshooter for them. Some guerrillas of the criminal sort caught the poor youngster, smashed his face to a pulp, collected a cup of his blood and tried to force his twelve-year-old sister to drink it, a barbarity that immediately provoked a fight between the American commander of the units and the men involved.25 I never saw atrocities at this depth of depravity and madness, but I saw enough that I don’t doubt that such tales are true.

One such case I will never forget because it took place in my own outfit after Hendrickson and I separated. It was one of those many instances in which guerrilla underlings acted on their own and only afterward told their superiors what had taken place. In this instance a spy was bled to death, and each guerrilla in the band that had captured him drank his blood. His heart was then torn from his body and roasted over an open fire, after which each guerrilla ate a bit of it. The whole ghastly business was done in public to impress civilians. Afterwards I asked the officer in charge how it had affected him. He said it made him feel brave. I was sickened, but I could not resurrect the victim, and to have executed the whole guerrilla troop responsible would have demoralized all my men, so I did nothing.

Yay Panlilio, an intelligent woman and seemingly a humane one as well, says she did all she could to insure that Marking’s guerrillas killed Japanese and traitors quickly and cleanly because she did not want their men to become sadists. But even she could be provoked beyond endurance. She acknowledges that once in an especially atrocious case she and Marking let their men beat some traitors to death, and that she personally killed one of the victims who had murdered a friend of hers and had then violated the corpse.26 In most guerrilla outfits collaborators were routinely executed, with or without benefit of a trial, usually by beheading, shooting, or being buried alive.27

No matter how callous it seems to say this, and since the Vietnam War no matter how unpopular, it comes down to this: we could not allow the Japanese to terrorize civilians with impunity or to employ spies among us without exacting a prompt and proportionate vengeance. Otherwise, no Filipino civilian would dare to aid us. We also had the new Philippine Constabulary to consider. A high proportion of men in it remained loyal to America in their hearts, but others became genuinely converted to the Japanese cause by persuasion, despair, or pay, or some combination of these; and there were many who fell somewhere in between. Those who were pro-American could not openly avow it lest their pro-Japanese colleagues betray them to the enemy. Of course, it was impossible for any outsider to sort them all out accurately, yet we could not disregard the Constabulary, for if the pro-Japanese elements in it were never opposed or molested they would dominate their fellows and make the Constabulary an effective force that would then allow the Japanese to release thousands of their own regular troops for duty elsewhere. As Russell Volckmann once put it, guerrilla life is no place for the tender-minded.28

The ideal way to deal with a suspected spy would have been to turn the person over to an ordinary civilian court for a formal trial under American or Philippine law. But there were no such civilian courts where we were, nor any regularly constituted court martial system either. After I became commander of Pangasinan province in the summer of 1944, I did the best I could: I organized a company of military police whose duty it was to apprehend anyone suspected of spying, or of committing murder, rape, robbery, or any other serious crime against a civilian. When a case existed against someone, he was arrested, brought before the officers of this military unit, and tried. It wasn’t a trial that would have pleased the American Bar Association, since those who passed judgment were mostly simple men untrained in the law, but it was a step above a kangaroo court.

A worse difficulty has been noted earlier: there were no jails. Thus, no matter what the nature of any serious crime or the care we took to treat the accused as fairly as we could, the accused was either found innocent and released or found guilty and executed. Even if we had had jails, or guerrillas willing to become mere jailers, prisoners would then have had to be fed and clothed, when we sometimes had a hard time feeding and clothing ourselves. Moreover, if a prisoner escaped his only practical course would be to flee to the Japanese for protection. This would mean that the vengeance of the cruel conquerors would then descend on any Filipinos who had helped guerrillas, aided in the capture of the criminal, or guarded him. When weighing the lives of many friendly Filipinos—and their families as well, remember—against the life of one spy, collaborationist, or criminal, real or suspected, normally there could be only one decision. The Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa once summed up the essence of the matter succinctly. When asked what to do with some prisoners when he lacked food for his own men, or any extra men to guard prisoners, he is supposed to have replied, “Let’s shoot them for the time being.”

Yay Panlilio acknowledges shooting prisoners before an impending battle, and also describes a grimly appropriate way in which Marking’s guerrillas dealt with one of their own best fighters who had raped a woman who had given them much rice. They told the man they would fake his execution: shoot over his head. Then he should fall as if dead in order to satisfy the woman he had wronged. But the firing squad did not shoot over his head.29

Nobody will ever know how many innocent Filipinos lost their lives because they lacked proper identification, or were a long way from home for no clear reason, or because either guerrillas or Japanese considered that they could not take chances. For instance, a collegian from Manila joined the underground and fraternized with Japanese officers to get information about them. Some guerrillas observed this, did not realize what the boy was trying to do, and ambushed him. Another from the same school was guarding some machinery at a private estate when local guerrillas got the mistaken idea that the machinery was to be sold to the Japanese, so they murdered him30

It is against this whole background that the reader should consider the disposition of two of the toughest spy cases I ever had to deal with. One day when we were fleeing from the Japanese, we crossed a river and holed up in a village where we hoped the enemy would not find us. Soon some men showed up who had not been with us when we crossed the river but who belonged to our organization. Acting on their own, they had dressed themselves in Philippine Constabulary uniforms, posed as members of the Constabulary, and questioned an old man whose clothing was made from gunnysacks. They told the man they were looking for Filipino and American guerrillas. Then they accused him of collaborating with guerrillas, which he indignantly denied. He insisted that, like themselves, he worked with Japanese. One of our phony Constabularymen then asked him how much the Japanese would give him if he led them to a Filipino or American guerrilla. He named a figure our men know to be accurate, and added other information that indicated that he was indeed on familiar terms with the Japanese.

I first became aware of the affair when some of our men dragged the culprit into the house where I was staying. He had been beaten unmercifully, and it appeared that his back was broken. I then asked some of the village people if they had witnessed the affair. They said they had, adding that they had no doubt that the stranger was a Japanese spy. I then told the guerrilla lieutenant concerned to finish what he had started and bury the victim, but to make sure nobody fired a gun since that would reveal our position to the Japanese somewhere across the river. That done, I assumed that another messy incident with another spy was over. Alas! It was not.

Three days later a woman who was a stranger to the district, and about eight months pregnant in the bargain, entered the village in search of the recently deceased “spy.” She said he was her husband. We arrested her and interrogated her about her alleged husband’s connections with the Japanese. She denied repeatedly and tearfully that he was a spy at all, and did so with such conviction that to this day I wonder if our men did not make a tragic mistake. But what to do with her? She was bound to hate us for having killed her husband and the father of her unborn child. If we released her and she went to the Japanese, either because she too had been a spy all along, or because she wanted to avenge her husband, the enemy would burn the village to the ground and murder all the one hundred or so people who had already risked their lives to give us aid and shelter. We guerrillas could probably escape during such a Japanese attack, but civilians have to stay where they gain their livelihood, so ill-advised lenience on our part would condemn them rather than ourselves. Yet no civilized person wants to kill a woman eight months pregnant; doubly so when he fears that her jeopardy may be due to ghastly misjudgment by some of his own men.

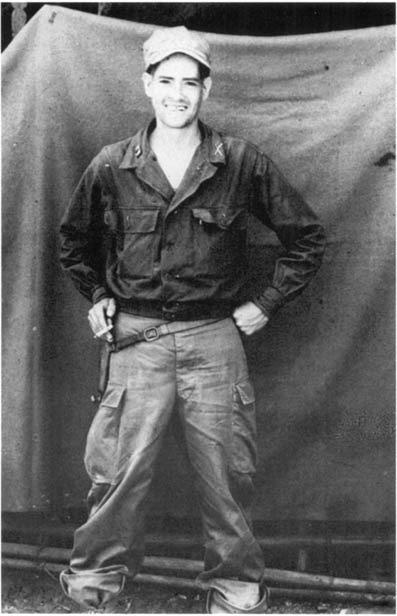

Ray Hunt, January 1945, shortly after the liberation of Luzon. Note cross-rifles and guerrilla rank of captain, later made official and retroactive to December 11, 1943.

Unless otherwise noted, all photos are from Col. Hunt’s collection.

Some of the guerrillas attached to Hunt’s headquarters, Pangasinan Military Area, in December 1944. Hunt is third from the left in the front row; his bodyguard, Lt. Gregorio S. Agaton, is fifth from the left.

Calesas in San Quintin, Pangasinan, where Hunt led a guerrilla raid on a Japanese garrison in January 1945.

Left, Lt. Joseph Henry, a mestizo guerrilla in Hunt’s unit who was wounded in combat. Right, Capt. Jesus (Jimmy) Galura, a PMA guerrilla staff officer.

A small group of PMA guerrillas, including three Filipinas, in late 1944. The girl farthest right is Herminia (“Minang”) Dizon. Santos, next to Minang, was an intelligence operator smuggled into the Philippines.

Amphibian flying boats move in above the U.S. invasion fleet in Lingayen Gulf as the Americans retake Luzon, January 9, 1945. Courtesy of the National Archives.

Above, the Villa Verde Trail near Yamashita Ridge, where savage fighting occurred between the Japanese and the 32nd Red Arrow Division. Hunt coordinated the guerrillas in that battle. Below, American soldiers battle the Japanese in steep jungle terrain in northern Luzon during the final months of the war. Both photos courtesy of the National Archives.

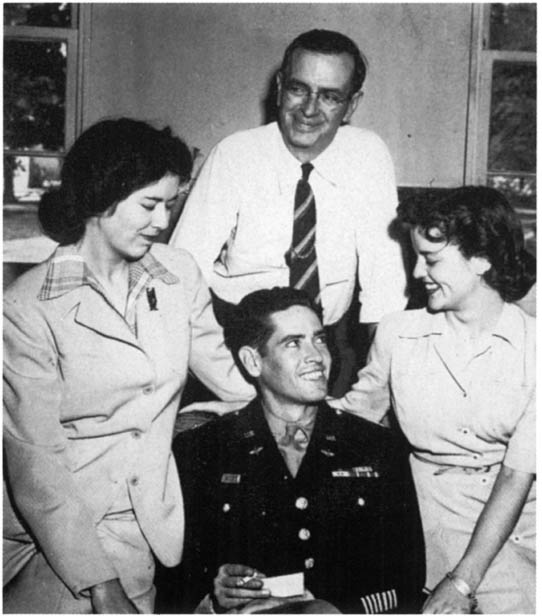

One of the rewards of heroism. Hunt is surrounded by Filipina beauty queens at Cuyapo, Nueva Ecija, on April 10, 1945.

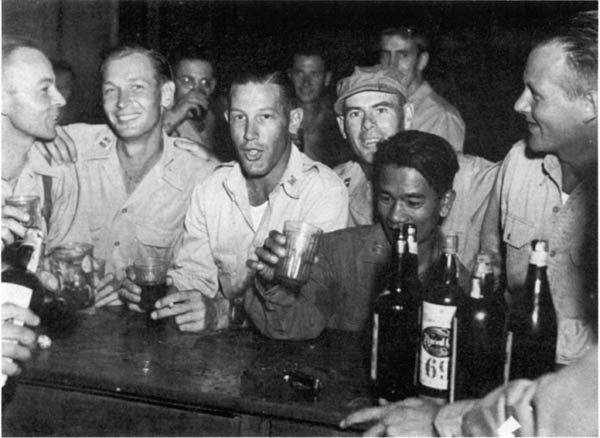

Guerrillas and liberating forces celebrate at a party in Rosales, Pangasinan, in late January 1945. Maj. Robert B. Lapham, commander of Luzon Guerrilla Forces, is second from left. Maj. Harry McKenzie, Lapham’s executive officer, is third from the right.

Seven American guerrilla leaders shortly after being decorated by Gen. Douglas MacArthur with the Distinguished Service Cross, June 13, 1945. Left to right: Maj. Harry McKenzie, Maj. Robert B. Lapham, Maj. Edwin P. Ramsey, Brig. Gen. Manuel A. Roxas (first postwar president of the Philippines), Lt. Col. Bernard L. Anderson, Capt. Ray C. Hunt, Jr., Maj. John P. Boone, and Capt. Alvin J. Farretta.

Hunt is greeted at Jefferson Barracks, St. Louis, on July 19, 1945, by his father and two sisters, Joyce Beth Jurkanin, left, and Wanda Jean Cappello, right. For nearly three years, Hunt’s family didn’t know if he was dead or alive.

Captain Ray C. Hunt, Jr., shortly after his return home from the Philippines. He was promoted to Major the following December.

Al called a meeting of himself, myself, Greg, a few of the guerrillas, the village leader, and six villagers. We impressed upon the woman with the utmost seriousness, both in English and in her own Ilocano dialect, that she must never say a word to anyone about anything that had happened among us, and told her that if she did talk we would hunt her down and kill her. Then we took a desperate chance and let her go. She left with tears in her eyes, seemingly of gratitude, but who could ever know?

The second case was as excruciating as this one, and infuriating in the bargain. Professional soldiers, and most writers on military subjects too, like to believe that wars are won by brains and bravery. It seems much less heroic and inspiring to attribute victories to the efforts of spies, though good intelligence work has decided more wars than is generally admitted—or even known. A major reason is that spying is an equivocal business. Some spies are patriotic idealists, but many are victims of compulsion, and many more are scurvy characters motivated by nothing nobler than obscure private passions or the need for extra money. Those of the latter sort, if caught, can often be induced to change sides. The British were particularly successful “turning around” German spies in World War II. I have sometimes been asked if I ever “turned a spy around.” I never tried: it always seemed too risky.

Like the Japanese though, we did employ a lot of spies, both male and female. Some have claimed that women make better spies than men because, allegedly, they do not become obsessed with their jobs; when not actually engaged in spying they think little about it and maintain their psychological balance better.31 I am unconvinced. Some women unquestionably make excellent spies, but I don’t think greater detachment or supposed superior psychological balance has anything to do with it. The most successful female spies we had were those who were at ease socially with Japanese officers in all kinds of situations. One of our best was a woman I shall call Dolores. The most charitable way to describe her prewar career would be to say that she was self-employed on the streets of Manila. Whatever her antecedents, she was energetic, thorough, smart, and brave. She made friends easily with Japanese officers, slept with a lot of them, and got much useful information from them which she rolled up in her hair curlers.

One day we heard that she was dead. We assumed that she had been caught and executed by the Japanese. We were astonished to learn that she had been picked up on suspicion by a temperamental Filipino guerrilla lieutenant of ours who had accused her of being a spy for the enemy. He had then simply shot her without a trial, without even so much as consulting anyone of higher rank! I don’t recall Al’s reaction, but I was momentarily blinded with fury. Had the lieutenant been where I was, I probably would have given him just what he gave Dolores. Since he wasn’t present, we assembled a company of men and went looking for him. By the time we found him, I had cooled off enough to recollect that he had always been an energetic and loyal officer. His demeanor, however, very nearly restored my original rage, for I had never talked to a Filipino who simply stared at me with unconcealed insolence and whose whole bearing breathed insubordination. We had him disarmed and then asked him why, on mere suspicion, he had killed probably our best secret agent? He said he hated the “Hapons” and lived to kill as many of them as he could. He had heard that the woman was a prostitute for the “Hapons.” She had been unable to identify herself or explain why she was so far from home, so he had concluded that she was a Japanese spy and shot her.

Rage surged back through me. How could this insolent, surly bonehead have taken it upon himself to kill out of hand a brave and valuable woman? But I will say for myself that at least I did not altogether stop thinking. We picked at random some twenty of the lieutenant’s men and questioned each one separately about what he thought of his leader. All replied much the same: the lieutenant was tough as nails but basically fair and honest, and he hated the Japanese obsessively. Then Al and I talked again to the lieutenant himself. Finally we concluded that, however wretched his judgment had been he had probably acted from sincere conviction. Enough damage had been done already, and we did not want to lose anyone who wanted so badly to fight the enemy, so he was reprimanded as thoroughly as American vocabularies permitted and given back his guns. A few weeks later he was killed doing what he liked best, fighting the “Hapons.”

The famous aviator Charles A. Lindbergh, who toured the Pacific during the war, came away convinced that American treatment of enemy prisoners and suspected spies was not much better than that of the Japanese, even though we professed to be fighting for civilization. Of course, it is generally wise in war to treat prisoners kindly since this gives enemy soldiers an incentive to surrender and save their lives. Moreover, once they are prisoners skilled interrogators can usually get useful information from them. But the Japanese were always exceptional: they simply did not play by rules of any kind. When an occasional one was captured, he could never be trusted, just as we guerrillas could not trust or take chances with real or suspected Japanese agents. Colonel Lindbergh, flying around in an airplane and penning memoirs afterward, simply never had to deal with the sickening quandaries that cropped up so often in the relentless ground war. Trying to distinguish “moral” from “immoral” conduct during struggles to the death with remorseless enemies has always seemed fruitless to me.