Sung Portions of the Medieval Mass, Roman Rite

Christian Liturgical Music from the Bible to the Renaissance

MARGOT FASSLER AND PETER JEFFERY

THE NEW TESTAMENT AND THE EARLY CHURCH

The earliest Christian musical tradition developed from a variety of sources, but especially from the Jewish and pagan customs of singing at gatherings around a meal. Though New Testament writers testify that some early Christians continued to worship in the Temple and the synagogue, even while gradually coming to feel unwelcome there (Acts 2:46–3:3, 5:20–42, 13:13–51, 17:1–15), neither the Temple nor the synagogue is likely to have been the immediate source of early Christian music. The elaborate Temple ritual, with its animal sacrifices, professional priests, and levitical “orchestra,” could not have been duplicated in early Christian gathering spaces. In synagogue services, it is unclear whether any psalmody was used before 70 C.E., when attempts were made to develop the synagogue liturgy into a partial substitute for the destroyed Temple cult through the use of psalmody, the shofar, and certain other practices commemorating the sacrifices. Thus the most distinctively Christian gatherings of the early church were not Christianized synagogue or Temple services but, rather, the common meals, related to the ritualized Jewish banquets celebrated by groups of disciples gathered around an authoritative Rabbi or teacher, or the family-centered-meals that still survive today in Jewish homes: at the Friday night supper that opens the Sabbath, for instance, or (especially) the Passover seder.

Held in private homes during the first two centuries, such meals typically included Scripture reading, religious instruction, prayer, and singing, and they often had messianic or eschatological significance. We find examples in the literature of Qumran,1 the Letter of Aristeas,2 and especially Philo’s The Contemplative Life.3

Among the pagans, too, common banquets had long provided important occasions for philosophical and religious discussion as well as for religious and secular song. This was the original meaning of the word symposium (literally, drinking together), as illustrated in the dialogues of that name written by Plato, Xenophon, and Plutarch. The banquets celebrated by the early church were seen as commemorating, and in a sense continuing, the meals Jesus himself had celebrated with his disciples, and from such meals the Christian eucharist and the lamplighting or vespers services developed. The similarity of the early Christian feasts to Jewish and pagan practices alike provides the context for interpreting our earliest evidence regarding Christian music. The repeated admonitions of early Christian writers to shun intoxicating pagan revelry in favor of spirit-filled rejoicing (Eph. 5:18–20) echo Philo and other Jewish writers.4 The musical practices of Philo’s Therapeutae so closely resemble early Christian music that Eusebius of Caesarea, the fourth-century “father of church history,” insisted that Philo must have been describing a Christian group.5

The oldest sources describe early Christian music with words such as “psalms, hymns, and spiritual songs” (Eph. 5:18). Rather than the names of three musical genres, these words were probably loose synonyms used interchangeably with other terms as well. From a modern perspective, however, it is helpful (albeit anachronistic) to distinguish three types of texts that were sung during the early period: (1) psalms, namely, the 150 Psalms of the Bible; (2) canticles or odes, psalmlike poems found in other books of the Bible (e.g., Exodus 15, Habakkuk 3); (3) hymns, which are nonscriptural compositions of any kind, whether anonymous or written by poets whose names we know. The earliest Christian hymns often resemble the Psalms and canticles in form and structure, but most include at least some specifically Christian content, usually dealing with the identity of Christ or with the meaning of his life and death. The pagan writer Pliny the Younger describes Christians of the early second century as singing “a hymn to Christ, as to a God.”6 The texts of many such christological hymns are quoted in the New Testament itself (e.g., John 1, Phil. 2:6–11, Col. 1:15–20), and an early collection of hymns of this kind may survive in the so-called Odes of Solomon.7 Indeed, the apocryphal Acts of John describes Jesus singing a song about himself while leading a dance after the Last Supper (cf. Matthew 26:30).8 Though Gnostic and other heretical hymnodists provoked sporadic attempts to restrict the use of nonscriptural hymns in favor of the biblical psalms and odes,9 Christian poets and composers never ceased to create new hymns throughout the history of the church.

Some of the earliest hymnodists seem to have been bent on promoting heterodox Christologies. The first important orthodox hymnodists include Ephrem the Syrian (c. 306–373 C.E.), who composed sermonlike memre and strophic madrashe, and Ambrose of Milan (c. 339–397), whose strophic Latin hymns are still sung today in modern translations. The most significant Greek hymnodists were both Syrians by birth: Romanos the Melode (sixth century), who may have been of Jewish origin and who mastered the kontakion, or metrical sermon; and John of Damascus (seventh to eighth centuries) whose kanons presented a series of stanzas meant to be interpolated among the verses of the biblical odes. Monostrophic or single-stanza hymns, most generally called troparia (though they also have other names), were composed by many authors; for instance, the troparion “O Only-begotten Son” of the Byzantine liturgies’ little entrance is attributed to Emperor Justinian (483–565). The Gloria patri (“Glory be to the Father’ ‘) and the Trisagion (“Holy God, Holy Mighty One”) are used in the liturgies of almost all Eastern and Western churches.

THE CONVERSION OF THE ROMAN EMPIRE

The conversion of the emperor Constantine at the beginning of the fourth century signaled an important shift in Christian musical history, though the gradual transition from a pagan to a Christian empire took several centuries. With the end of persecution, Christians were free to leave their house-churches and to worship openly, and as a result the liturgy began to develop in two new directions, cathedral liturgy and monastic liturgy.

“Cathedral” or “Stational” Liturgy

In each city of the empire, the entire Christian community gathered together for worship under the leadership of the bishop, assisted by presbyters (elders or priests), deacons, and lower-ranking clergy. These celebrations were held in the great basilicas, modeled on imperial courthouses, built to hold the large crowds of new Christian worshipers. On each major feast the entire clergy and populace of the city would assemble in a different church and then go in procession to the basilica where the eucharist would be celebrated (the station). Thus in the course of a year, celebrations would be held throughout the whole city. The most important station, reserved for the most solemn days, was at the cathedral, the bishop’s “headquarters” church where his cathedra (chair) was located.

With its large crowds of worshipers and numerous clergy, its impressive buildings and lengthy processions, stational liturgy soon became more elaborate and formalized than worship had been in the days of the house-churches. Because the bishop was now an imperial as well as an ecclesiastical official, the Christian liturgy absorbed some of the elements of secular ceremonial that his civil office entitled him to use. This privilege included the right to be met by a choir when he entered the basilica at the beginning of the liturgy, a practice that may have developed into what we know as the introit.

Congregational singing was also important. It is frequently mentioned in the sermons of the great Church Fathers of the late fourth and early fifth centuries. Most often, congregational singing took the form of responsorial psalmody, in which a soloist (an ordained reader or cantor) sang the verses of a psalm, and the congregation joined in at the end of each verse with an unvarying refrain, usually derived from a verse of the same psalm. This type of psalmody is first mentioned in connection with vigils, services that lasted much of the night and ended in the morning. But responsorial psalms were also included among the scriptural readings at mass, which is why they were mentioned in so many sermons of the period. They were also sung during communion and at other points during the mass and office.

Along with responsorial psalmody two other types of psalmody were also important in the cathedral office. St. Basil described one of them in a letter dated 375:10 In antiphonal psalmody two choirs, or two halves of the congregation, took turns singing the verses in alternation (i.e., one choir sang the odd-numbered verses, the other the even-numbered ones). Later, there was also a refrain or antiphon sung after each verse, though Basil did not mention this. In its classic Western form, antiphonal psalmody ended each psalm or group of psalms with the trinitarian hymn Gloria patri. In direct psalmody the entire psalm was sung straight through by all with no alternation or refrain.

Monastic Liturgy

Many lay Christians of both sexes wanted a more rigorous and heroic spirituality than the emerging civic Christianity seemed to offer. They found it in the wilderness outside the cities, particularly in the deserts of Egypt, where they grouped together in the first monastic communities. The worship of the monks aimed at the ideal of unceasing prayer (1 Thess. 5:17) by means of a regular cycle of daily and nightly communal services that featured recitation of the psalms and meditation on the Scriptures as well as group prayer. Most psalms were chanted by a soloist while the other monks listened, though the last psalm of each office was performed responsorially with the word Alleluia serving as the refrain. Monastic liturgy tended to be more austere than the cathedral type, partly because of the simpler and more ascetic way of life followed by the monks in the wilderness, and also because the monastic communities were originally made up of laymen or laywomen with few or no clergy. Originally, the monks were reluctant to use the nonscriptural hymns of the cathedral liturgy, with their beautiful poetry and melodies. This reluctance gradually weakened, however, as the cathedral and monastic types of worship began to merge.

THE EARLY MEDIEVAL SYNTHESIS

The Blending of the Two Types of Liturgy

Even as they were first emerging during the fourth century, the cathedral and monastic types of worship were already influencing each other. Some monastic communities that were established in or near cities participated in the services of the stational liturgy in addition to their own monastic services; this was so in Jerusalem when Egeria described its liturgy during the early 380s. In addition, as monks who had originally been laymen became increasingly clericalized, even to the point where it was normal for a monk to be a priest, they took part in both cathedral and monastic liturgies. Thus the fully formed liturgies of the Middle Ages were actually hybrid traditions, built up from varying syntheses of cathedral and monastic elements that were combined differently in each major center. Liturgical historians still disagree often about the cathedral and monastic elements and the processes by which they were mingled to form the rites we find in the earliest surviving liturgical books, most of which date from the seventh to the tenth centuries.

The monasticizing of the urban clergy along with other factors promoted a clericalizing of the liturgy, an increasing tendency to regard the liturgy as an activity carried out within the clerical community on behalf of the whole church, rather than as an act of the whole assembly. At the same time, membership in the Christian laity seemed less distinctive now that it included almost everyone in the empire. As liturgical traditions began to be written down and organized into liturgical books, and as literacy and education also became a largely clerical preserve, it was inevitable that the role of the laity in public worship would diminish considerably. More of the responsibility for singing fell to the choir, made up of low-ranking clergy. Thus most of the liturgical music that we have from the Middle Ages is the music of the monasteries, cathedral chapters, and other clerical and religious communities that were so numerous during the medieval period.

But two common misconceptions should be avoided. First, congregational singing and other forms of participation did not completely die out during the Middle Ages. Second, the pressures that tended to clericalize the liturgy did not spring from a desire for musical expertise and virtuosity, as some modern writers, seeking to discourage the use of Gregorian chant by modern congregations, have claimed. Such a desire would in fact have been completely contrary to the early monastic spirit.

The Medieval Repertories

Initially, every city or region seems to have developed its own local rite and chant repertory, with particular chant texts, prayers, readings, and other materials fixed into standardized orders of service according to the local liturgical calendar. This may have happened first at Jerusalem, where a complete annual cycle of responsorial psalms for the mass already existed in the early fifth century; it now survives only in the old Armenian lectionary, translated from the lost Greek original.11 The first real chant book, containing the texts of all the scriptural and nonscriptural chants, arranged by the date and time each text was sung during the year, was also compiled at Jerusalem, probably by the seventh century; it survives only in a Georgian translation from the original Greek, and thus bears the Georgian title Iadgari. In the Latin West, such a book was called an antiphonale; the earliest surviving copies, dating from the eighth century, represent the uses of Milan and Rome. The earliest antiphonalia that are fully supplied with musical notation for the melodies date from the early tenth century. Notated Greek manuscripts survive from the mid-tenth century onward.

At first, the musical signs, or neumes, indicated only the general direction of melodic movement up or down; they served mainly to assist the memories of singers who were well-trained in the chant tradition. Between the eleventh and the thirteenth centuries, both Western and Eastern notational systems were refined so as to show exact pitch, but this was done in different ways. In the West it meant the invention of the staff, which is still the basis of Western pitch notation today. The Byzantine East opted for a “digital” system, in which each sign indicated a specific diatonic interval, higher or lower than the pitch indicated by the preceding sign. This notation was simplified and modernized in the early nineteenth century, when a few of the signs were retained to represent invariable degrees of the diatonic scale.

Eventually the traditions of the most important centers began to overwhelm, replace, or merge with those of the smaller and less powerful ones. Among the most significant were Orthodox Christians—divided by a variety of languages—and Roman Catholic Christians.

Among Greek-speaking Orthodox Christians, the two strongest traditions—the Divine Liturgy of Constantinople’s cathedral (Hagia Sophia) and the monastic office of Palestine—gradually merged to form what we know as the Byzantine rite. It absorbed or supplanted the smaller, more local traditions of Antioch, Jerusalem, Alexandria, southern Italy, and even the cathedral office of Constantinople itself. This hybrid Byzantine tradition was introduced by Greek Orthodox missionaries into the Slavic world, where it survives today (after many adaptations) in the Bulgarian, Russian, LTU Rusin, Serbian, Ukrainian, and Rumanian chant traditions.

Eastern Christians who spoke languages other than Greek, and who subscribed to theological views unaccepted by Rome and Byzantium, managed to hold onto more of their own traditions. The Armenian church, for instance, derived its liturgies from the pre-Byzantine Greek worship of Jerusalem, experienced periods of Byzantinization and Romanization, but in general retained its independence. The neighboring Georgian Orthodox church, on the other hand, originally followed a later form of Jerusalem ritual, but about the twelfth century was completely Byzantinized. Many Armenian and a few Georgian medieval manuscripts contain musical neumes that cannot now be deciphered. The Armenian notation, like the Greek, was modernized and simplified in the early nineteenth century.

Syriac-speaking Christians divided into three main traditions: First, the Jacobite, west Syrian or Syrian Orthodox (Monophysite) church preserved translations of much Greek material from Jerusalem and Antioch that was lost from Greek-speaking Christianity after these early centers were Byzantinized. (In more recent times a branch has also been established in India; part of it has entered communion with Rome and is known as the Malankar rite). Second, the east Syrian or Assyrian Orthodox (Nestorian) church of the East, in the Persian Empire in Mesopotamia, possessed the only ancient liturgical tradition that developed outside the Hellenistic world; a group that united with Rome in the sixteenth century is known as the Chaldean church. During the Middle Ages the Assyrian tradition was brought all the way to China and India by Nestorian missionaries; the Catholic branch that survives in India is known as the Malabar rite. Third, the Maronites of Lebanon, united with Rome since the Crusades, preserve an independent synthesis that seems originally to have been more closely related to the east Syrian tradition but now shares a great deal with the west Syrian tradition also. None of these three traditions ever adopted written musical notation, and their melodies are transmitted orally to this day. However, the Syrian Melkites, or “Royalists,” who sided with the Byzantine emperor during theological controversies, gradually adopted the Byzantine liturgy in Syriac translation, producing a fourth Syriac liturgical tradition. This adoption included unsuccessful attempts to introduce Greek neumes, and a few neumated Melkite manuscripts still survive.

The chant of the Coptic Orthodox (Monophysite) church of Egypt includes some material of Greek origin, but it never developed a notational system, despite some limited medieval attempts to do so. As a result, much of the ancient melodic repertory has been lost. Only the music for the Divine Liturgy and the most common other services has been passed down by oral tradition.

Though the Ethiopian Orthodox church was theoretically a branch of the Coptic church, much of its liturgy, particularly its chant repertory, developed in relative isolation from Egyptian traditions. A fully developed notational system emerged in the sixteenth century, and is still in use today.

Hardly any evidence survives regarding the chant of the Nubian church, which once existed in what is now the Sudan, but which by the fourteenth century had been completely overwhelmed by Islam.

Gregorian Chant

In the Latin-speaking West, the Gregorian chant tradition ultimately prevailed. Gregorian chant may have been a synthesis of Roman and northern (Gallican or Frankish) traditions, for the earliest surviving manuscripts (from the eighth to the tenth centuries) do not come from Rome but from farther north, mostly from within the Frankish Kingdom or Carolingian Empire. Thus they date from the period when a standardized liturgy of Roman origin (but one that included non-Roman elements) was being assembled and imposed on all the churches in the domain ruled by Charlemagne (c. 742–814) and his successors. But scholars still fiercely debate the origins of the chant along with its problematic relationship to its namesake, Pope Gregory the Great (reigned 590–604). Though tradition credited Gregory with the compilation of the antiphonale, there seems to have been no music notation in use during his time. More troubling still, the earliest manuscripts from Rome (from the eleventh century) preserve a different tradition (usually called Old Roman chant), with most of the same texts as Gregorian chant but with melodies that are somehow related yet quite different. Nevertheless, the medieval belief that the “Gregorian” repertory was Roman assured its eventual hegemony over most of the other Western local traditions. These included the Gallican chant of France (eighth-ninth centuries); the Beneventan and other traditions of southern Italy (early ninth century); the northern Italian traditions of Ravenna and Aquilea (not much later than the early ninth century); and the Mozarabic chant of Spain following the withdrawal of the Muslims during the eleventh-century Reconquista (though the Mozarabic rite has been permitted to survive in one chapel of the Toledo cathedral). By the thirteenth century, Gregorian chant was being used even in the papal court, and in this form, as part of the liturgy of the Roman curia, it supplanted even the Old Roman chant that had survived up until then in the Roman basilicas. Only the local tradition of Milan, called Ambrosian chant because it was alleged to have been created by St. Ambrose, managed to survive into the twentieth century, despite some Romanization during the sixteenth century.

Genres of Chant

In all of these medieval traditions, the older practices of responsorial, antiphonal, direct, and solo psalmody survived, though they were sometimes abbreviated or altered in various ways: verses were omitted, refrains were sung less often. In the West, some psalms that had traditionally been direct or solo came to be performed by alternating choirs as if they were antiphonal; in the East the opposite sometimes happened. Antiphonal psalms, responsories, and strophic “Ambrosian” hymns were the main genres of chant in the medieval Western office, which retained a distinction between cathedral and monastic forms. Though they used most of the same material, each was differently arranged, the monastic arrangement being based on the early sixth-century Rule of St. Benedict. Kanons and troparia dominated the Byzantine monastic office, which eventually completely replaced the Constantinopolitan cathedral office.

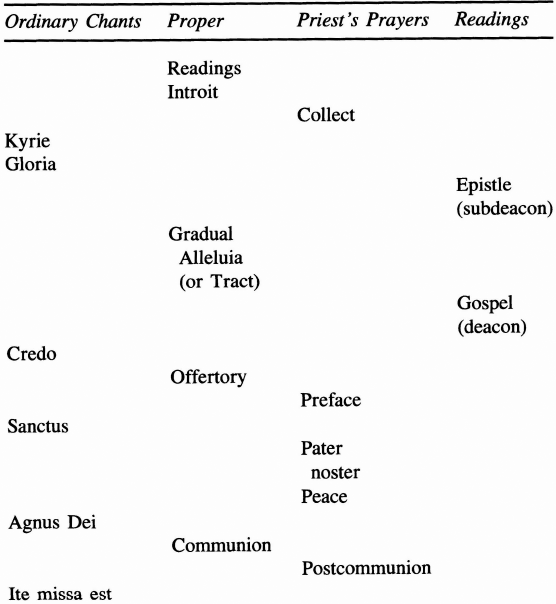

In the medieval Roman mass, the antiphonal introit psalm was shortened to include only the antiphon, the first verse of the psalm, and the Gloria patri, while the responsorial offertory and antiphonal communion chants eventually lost their verses altogether. The responsorial psalm following the first reading was shortened to a refrain and one verse; in time it came to be called the gradual because it was sung from the steps (gradus) of the ambo. (The replacement of the shorter medieval graduals by longer responsorial psalms has been one of the more striking and popular of the reforms following Vatican II.) The alleluia before the gospel had also been a complete responsorial psalm at Jerusalem but seems always to have had only one verse in the West. On the other hand the tract, solo psalmody that replaced the alleluia during Lent, retained many verses, but by the late Middle Ages it was being sung antiphonally in some places. All of these chants varied both in text and melody for each day of the liturgical year. The series of chants proper to each liturgical day therefore became known as the proper of the Mass for that day (see table 1). The annual cycle of proper Mass chants was the first part of the Gregorian chant repertory to be collected and written down in a book, called the Antiphonale Missarum or the Graduale (perhaps a hint that the graduals were collected first?). The responsorial graduals and Alleluias and the solo tracts were collected separately in a book for the soloist called the Cantatorium.

The Roman mass had other chants with relatively fixed texts that did not vary much from day to day; these came to be called the Ordinary of the Mass, in contrast to the proper. Of the six chants typically included, four were short: The Kyrie eleison probably marked what had originally been the point where the participants in the stational procession, upon arriving at the church for Mass, sang a litany while entering and approaching the altar. The Sanctus, or canticle of the heavenly seraphim (Isaiah 6:3), was sung within the anaphora, separating what came to be called the Preface from the Canon Missae. The litanic Agnus Dei, introduced by Pope Sergius I (687–701), was sung during the fraction of the bread like the proper confractorium of the Gallican Mass. The Ite Missa est, changed to Benedicamus Domino on lesser days when the Gloria in excelsis was omitted, signaled the dismissal. The older of the long ordinary chants, the Gloria in excelsis, or canticle of the angels (Luke 2:34 plus additional material), was sung in the morning office in most other rites. In the Roman mass it was at first sung only on Christmas, perhaps following the gospel story in which it occurs (Luke 2:13–14). Pope Symmachus (498–514) is said to have authorized that it be sung on other major feasts when the mass was celebrated by a bishop, and it may then have migrated forward to its modern position following the introit and Kyrie. In this position it corresponds to the morning chants that began the mass in certain other rites: Daniel 3 (in the Septuagint, the Song of the Three Children) and Luke 1:68–79 in the Gallican mass, Psalm 95 in the Byzantine Divine Liturgy. During the eighth century, the Credo, or Nicene Creed, was inserted into the Western mass after the gospel, though it was not sung at Rome until 1014. In other traditions, the Creed received other positions, such as just before the anaphora (in the Byzantine Divine Liturgy) or before the Lord’s Prayer as a preparation for communion (in the Mozarabic mass).

In the East, variability was more typical of the office, much less so in the Divine Liturgy, where, for instance, even the types of chants that could vary did not vary every day (see table 2). For the prokeimenon (the responsorial psalm that precedes the reading from the Apostle), the alleluia, and the koinonikon (the chant accompanying the communion of the clergy) small collections of a few dozen texts were used on multiple occasions during the year. For the eisodikon (the entrance chant) and the cheroubikon (the hymn sung at the Great Entrance when the bread and wine are brought to the altar), the same text was used almost always; alternative texts were substituted on only a few occasions during the year.

NEW MEDIEVAL DEVELOPMENTS

Notation and Music Theory

Once the basic repertories were formed, musicians began to seek ways to standardize and improve the teaching and performance of chant. This led to the widespread adoption of the system of the eight church modes, which probably originated in seventh-or eighth-century Palestine, and which spread to Syria, Armenia, Byzantium, and the West during the two centuries following. It also led to the development of music notation in both the Latin (by about 900) and Greek churches (by about 950). These developments were further refined by the creation of a new literature of music theory, one that adapted some of the concepts and terminology of classical Greek music to describe such musical phenomena as the range and tuning of the available pitches and the characteristics of the modes. This development went further in the West, where theoretical literature began to emerge in the ninth century with the writings of such figures as Aurelian of Réôme (fl. c. 840–850) and especially Hucbald of St.-Amand (d. 950), who relied for their information about classical Greek music upon such late antique Latin writers as Boethius (c. 480–524), Cassiodorus (c. 485–580), and Isidore of Seville (c. 560–636). These additions culminated in the invention of the staff, more or less as we know it today, by the most important medieval Western theorist, Guido of Arezzo (d. after 1033). He is also credited with organizing the solmization system that developed into our “Do, Re, Mi. …” Over many centuries, the synthesis of ancient Greek terminology, the modal system, and the Gregorian chant repertory grew into the basis of the highly refined music theory so characteristic of Western classical music today.

New Western Forms: Ninth through Eleventh Centuries

In the East, ninth-century Constantinople began to eclipse Palestine as the chief center of Byzantine hymnography, with the activity of monks like Theodore the Studite (759–826), Joseph the Hymnographer (d. 816), and the nun Kassia. In the West, the standardized repertory of Gregorian chant was now in use almost everywhere, and in many regions new types of music and texts were being created to decorate and expand the repertory, particularly in the Carolingian Empire, England, northern Italy, and Benevento. Both the textual and musical styles of the new material differed somewhat from region to region, and everywhere they differed from the classic Gregorian corpus. Where the texts of Gregorian chant were frequently excerpted and paraphrased from the Bible, the new texts were more often poetic or literary, full of biblical allusions but not extracted from any single biblical passage. Much of the new music was monophonic, like the chant itself, a single vocal line of great sophistication and beauty but often different in style from the older Gregorian melodies. Some of the new music was polyphonic, however, consisting of one or more additional harmonizing melodies to be sung simultaneously with the chant.

Although scholars have not yet established a fully consistent terminology for the new monophonic chants (the medieval terminology was inconsistent also), we can divide them into four broad categories: (1) pneumata or neumae, (2) tropes, (3) prosulae, and (4) sequences. From the testimony of ninth- and tenth-century writers such as Amalarius of Metz (c. 780–850/1), and the parallel witness of the earliest chant manuscripts, it is clear that there was a tradition of singing decorative, untexted melodies, the neumae, at various points in the mass and office.12 Neumae were often sung, for example, following the gospel antiphons (i.e., the antiphons of the canticles Luke 1:46–55 and 1:68–79) at lauds and vespers, and at the close of the alleluia at Mass, where they were often called jubili or sequentiae. In a famous passage, Notker Balbulus (d. 912), the poet of St. Gall, spoke of his difficulty in remembering these very long melodies that were sung at the alleluia.13 Unfortunately, the evidence for reconstructing this early practice, which existed, after all, in an oral tradition, is slim, and it had apparently diminished greatly by the close of the tenth century, the period from which we first have substantial numbers of chant manuscripts.

Example 1. Beginning of the Gloria in Excelsis Deo with interpolated tropes. From the manuscript Vatican City, Bibliotheca Apostolica Vaticana, MS Vaticanus Urb. lat. 602, ff. 34r-36v, as published in John Boe, ed., Beneventanum Troporum Corpus, vol. 2: Ordinary Chants and Tropes for the Mass from Southern Italy, A.D. 1000–1250, part 2: Gloria in excelsis, Recent Researches in the Music of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance, vols. 23–24 (Madison, Wisc., A–R Editions, 1990), pp. 149–50.

Translation: GLORY TO GOD IN THE HIGHEST

[Trope 1:] Whom the citizens of heaven proclaim with lofty voice to be the Holy One.

AND PEACE TO PEOPLE OF [GOD’S] GOOD WILL.

[Trope 2:] As the [angelic] ministers of the Lord promised to people on earth through the incarnate word.

WE PRAISE YOU.

[Trope 3:] In your praises the morning stars persevere.

The manuscript tradition is far stronger for the three other categories. Tropes, additions of both text and music to Gregorian chants, were created in the greatest numbers to accompany introits;14 but certain other chants of the proper (offertories and communions) and of the ordinary of the Mass15 could also have tropes (see example 1).

Prosulae, purely textual additions to the melismatic sections of Gregorian chant (i.e., places where many notes had originally been sung to a single syllable) were written especially for alleluias and Kyries, as well as for certain melismas in offertories, Glorias, and the great responsories of matins (see example 2).16

Example 2. Beginning of a Kyrie in two versions: (top) melismatic version without prosula; (bottom) syllabic version with prosula Fons bonitatis. From the manuscript Naples, Biblioteca Nazionale, MS VI.G.34, 25v and 29v, as published in John Boe, ed., Beneventanum Troporum Corpus, vol. 2: Ordinary Chants and Tropes for the Mass from Southern Italy, A.D. 1000–1250, part 1: Kyrie eleison, Recent Researches in the Music of the Middle Ages and Early Renaissance, vols. 20–21 (Madison, Wisc.: A–R Editions, 1989), pp. 116–17.

Translation: [Top:] LORD, HAVE MERCY

[Bottom:] LORD, fount of goodness from whom all good things proceed, HAVE MERCY.

The most important single addition to the Gregorian repertory, the sequences, constitute a liturgical genre in their own right, with a history extending for several centuries. Although they may well have begun as a kind of prosula for the long neuma sung after the alleluia at mass, by the end of the ninth century, sequences, or proses (as they are also often called), were composed as independent pieces both east and west of the Rhine, as well as in Italy and England. Early medieval sequences, the type written from the ninth to the eleventh centuries, commonly are made up of prose couplets of varying lengths, with different music for each successive couplet of text.17 It was a common practice to quote from a particular alleluia melody at the opening of the sequence melody, thereby referring to the historical connection between alleluia and sequence. Many sequence melodies became popular and were set numerous times, the oldest ones being found in several traditions.

The liturgical texts and music created to expand upon the Gregorian repertory constitute the most important music composed in northern Europe during the centuries immediately following the Carolingian Renaissance. Although there is great variety in the texts and music of these repertories from region to region, most fall into specific genres whose liturgical function determines both the melodic style and the nature of the exegesis found in the texts. Introit tropes, for example, are expository, and serve to establish the theme of the feast; texts written for alleluia prosulae, on the other hand, offer praise along with the angelic hosts. Thus tropes, sequences, prosulae, etc., were designed to provide the scriptural texts of the Gregorian canon with medieval exegetical interpretations. It was also within these repertories that specific regions (and even individual religious institutions) customized their liturgical practices and preserved vestiges of the traditions displaced by the Gregorian repertory. Yet in spite of the widespread acceptance of tropes and sequences throughout Europe and in Italy, some institutions never used them to any great degree; for example, the Benedictine abbey at Cluny in France, famous for its elaborate offices and votive services, apparently never incorporated great numbers of tropes and sequences into its liturgy.

During this same period (ninth-eleventh centuries), new monophonic melodies continued to be generated in the older musical genres of Gregorian chant. Many new melodies for the chants of the ordinary of the mass were created throughout northern Europe, and for the first time they began to be written down in a kind of book known as the Kyriale.18 This was also a time of great expansion of the office, with new texts and music being composed in abundance for the hundreds of new saints added to the calendars of various regions and centers. Like the trope and sequence repertories described above, these office texts and music were, to a great degree, particular to specific regions in both the choice and ordering of pieces. They are significant resources for studying unique regional characteristics of medieval liturgies.19 Some new offices were modally ordered, their chants composed to pass through all the modes in numerical order. Rhymed offices or historiae had rhyming poetic texts that contrast markedly with the prose texts of the older repertory.

Organum, the practice of performing Gregorian chant polyphonically, usually with improvised harmonizing parts, is described in treatises of music theory as early as the tenth century. Octaves, fifths, and fourths were the preferred intervals, and the newly composed part (vox organalis) usually had only one note for each note of the original chant (now called vox principalis). Written examples of polyphony (differing melodic lines performed simultaneously) are scarce from this period, but the ones that survive suggest that a variety of techniques were being used to decorate the chant melodies. The most important polyphony to survive from before the early twelfth century comes in manuscripts from Winchester (c. 1000, polyphonic alleluias) and Chartres (late eleventh century, polyphonic alleluias and graduals).20

Western Liturgical Chant: Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

The Gregorian reform movement (named for Pope Gregory VII, 1073–1085) began in the second half of the eleventh century, and within one hundred years it had inspired a variety of changes in western European musical and liturgical practices. These changes can be observed not only in the liturgies of newly formed religious orders—the Cistercians and the Augustinian canons regular, for example—but also in the liturgies of cathedrals, especially in dioceses with reform-minded bishops. Augustinian canons, the group most closely associated with the specific agenda of the Gregorian reform movement, usually followed the liturgical use of the diocese in which their particular house was located. But no matter where they were located, Augustinians were particularly fond of sequences and led the way in the development of the new style of sequence that emerged in the late eleventh century and came to triumph throughout northern Europe in the century following. Late sequences, like their predecessors, were organized in double versicles, but their texts were written in accentual rhythmic poetry; this change in poetic style affected musical style as well: many late sequences were designed so that each textual unit, be it phrase, line, or strophe, had its own sharply marked group of notes, and thus the structure of the music perfectly reflects the text. Certain carefully constructed melodies were set repeatedly, such as the famous melody “Laudes crucis,” providing a plan for great numbers of new texts.21 The Augustinian interest in sequences did not extend to tropes for the propers. In fact, whenever possible, these were omitted from the liturgies they inherited.

The best known of all liturgical and musical reforms of the twelfth to the thirteenth centuries are those of the Cistercians, an order of reformed Benedictine monks. The Cistercians attempted to return to a strict interpretation of the Benedictine rule and thus sought a liturgy and music that reflected their understanding of what liturgical practice had been in Benedict’s time, the sixth century. According to the writings of Chrysogonus Waddell, the leading modern authority on the subject, the first Cistercian liturgy was an adaptation of the liturgy and chant of Marmoutier. In subsequent decades, the Cistercians attempted to get back to the time of St. Benedict by studying the chant of Metz (believed to be the purest dialect of Gregorian chant) and the hymns of St. Ambrose as preserved in the Milanese tradition. Standardized in the late twelfth century, the Cistercian liturgy and chant is essentially Gregorian, but has certain striking modifications. Many chants of both the mass and office were reworked to fit the Cistercian understanding of the modes and were stripped of very long melismatic passages as well. The hymns of the office were reordered and only a small group of these pieces were retained.

Because the reform movement focused great energy on the secular clergy, it fostered interest in cathedral liturgies and the music written for them. Just as the twelfth and thirteenth centuries witnessed the building of many new Gothic cathedrals in western Europe, they also saw a refurbishing of the liturgies designed to fill these buildings. Although very few liturgical books survive from cathedrals of the twelfth century and earlier, many books remain from the thirteenth century, including a representative selection of ordinals, liturgical books that provide detailed ceremonial directions as well as incipits for the mass and office chants throughout the entire year. Thus, complete outlines of the thirteenth-century liturgies from several cathedrals in France, including Chartres, Amiens, Bayeux, and Laon, for example, as well as from cathedrals in England, Italy, and centers west of the Rhine, including a magnificent fourteenth-century ordinal from Trier22 are available for study.

Medieval cathedral liturgies are characterized by a matins service with nine readings (as distinct from the Benedictine twelve). This characteristic is a reliable first step in distinguishing cathedral chantbooks and calendars from monastic ones. Northern European cathedral liturgies were still stational during the thirteenth century, with the bishop and his entourage visiting specially designated churches on appointed major feasts. In several French cathedrals, an elaborate vespers service was sung during Easter week, a practice that may have derived from the descriptions of ninth-century Roman liturgies found in the commentaries of Amalarius of Metz.23 Considerable evidence suggests strongly that proper tropes were never as important in cathedral liturgies as they were among some Benedictines. The commentator Johannes Beleth, writing-in Paris in the mid–twelfth century, stated that introit tropes were especially favored by monks,24 and the vast number of surviving manuscripts of tropes are indeed found in monastic rather than cathedral books.

Other monophonic repertories created in the twelfth-thirteenth centuries are less directly related to religious reform movements. The versus or conductus25 were composed in France to provide incidental music during the mass and office, and to ornament the Benedicamus Domino, the chant that closed each of the office hours.26 Elaborate musical plays written in the twelfth century and designed to be performed at the close of matins or vespers came to be associated with the special services put on by cathedral canons and choral vicars during the weeks immediately following Christmas.27

The new music written for the mass and office in these two centuries also reflected the increasing devotion to the Virgin Mary being felt throughout Europe in the period. By the end of the twelfth century, both monastic and cathedral liturgies commonly had special offices for Mary as well as an increasing number of feasts in her honor. Furthermore, previously existing marian feasts were elevated to higher ranks. They required an even greater number of special texts and music and thus provided a great number of marian sequences and hymns from this period.

Polyphony of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries

The first extensive repertories of written polyphonic music survive in four manuscripts from southern France. This Aquianian repertory consists primarily of versus, verse tropes for the Benedicamus Domino, and sequences. The manuscripts, which were prepared throughout the entire twelfth century and into the thirteenth, demonstrate changes in notational practice as well as in musical and poetic taste.28 Much of the music of the southern repertory differed from earlier polyphonic repertories like the alleluias of Winchester. Instead of the added voice being closely tied to the original chant, with one or a few notes for each note of the chant melody, the added voice in the Aquitanian florid style was freer and consisted of an elaborate countermelody. The added polyphonic voice was often the more active voice, providing a group of notes for each individual pitch of the original chant. As a result the chant melody came to be sung more slowly, in notes that were held a relatively long time. For this reason, this part came to be called the tenor (from the Latin for “holding fast”).

Although there are few correspondences between the polyphonic repertories of southern and northern France in the twelfth century, the few manuscripts that preserve the northern repertories testify to the importance of the florid or melismatic style there as well.29 The most important northern liturgical polyphony from the late twelfth-thirteenth centuries was apparently composed for the cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris. Notre Dame polyphony (as it is often called) was written first for the parts of the service that traditionally belonged to soloists—that is, the intonations and verses of the responsorial graduals and alleluias of the mass and great responsories of the office. The choir responded to the soloists in monophonic chant. The music, as preserved in manuscripts dating from the mid-thirteenth century, represents the practices of at least three generations of Parisian composers. The earliest layer of music consists primarily of organum purum, very long pieces with the original chant held in long notes while the added voice(s) are in florid or melismatic style. In sections where the original chant was melismatic, on the other hand, the added voices were composed in discant style, moving at approximately the same speed as the chant, with a small number of notes for each note of the tenor. Short sections consisting of a chant melisma in the tenor with added voice in discant style are known as discant clausulae.

At the end of the twelfth century and in the early thirteenth century, Parisian composers (and subsequently the theorists and notators who preserved their music) began to organize the polyphony into rhythmic patterns, slowly replacing a practice that had hitherto been rhythmically unpatterned. By the mid–thirteenth century, a liturgical polyphony existed that was expressed in rhythmic notation, so that, for the first time in the history of Western music, duration was indicated precisely. In this system long and short notes were organized into ternary patterns called rhythmic modes. Music notation that relies on these patterns is called modal notation. Later in the century, the notation became even more sophisticated as precise note shapes came to have specific rhythmic meanings. The classic form of this notation is called Franconian, after Franco of Cologne, a Parisian theorist who flourished in the third quarter of the thirteenth century.

Several genres of compositions grew out of the first layers of Parisian polyphony. Some popular melismas had numerous discant settings written for them. Because modern scholars think these settings were interchangeable in some instances, they are known today as substitute clausulae. By the early thirteenth century, it became common to set texts to the upper voices of substitute clausulae, and thereby the first motets were formed. The conductus, too, came to be set polyphonically in the first half of the thirteenth century.

Although the organa pura, the clausulae, and some early motets and conductus were meant to be sung within the liturgy, the great number of motets composed in the second half of the thirteenth century were increasingly secular in nature and many, clearly, were not designed for liturgical use. Yet the motet was the most important polyphonic genre of the century, and by writing such pieces composers learned to control three voices with different levels of rhythmic activity, thereby gaining the skills necessary to develop the more rhythmically complicated polyphonic liturgical music of the fourteenth century. It is well to remember, however, that although the polyphonic repertories dominate modern histories of the thirteenth- and fourteenth-century liturgical music, and even though they were the most innovative repertories of music created during the time, they would not have been performed in the monasteries and, indeed, even in most northern European cathedrals during this period. Throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Gregorian chant and the sequences prevailed throughout Europe as the common repertory of liturgical music.

THE LATE MIDDLE AGES AND RENAISSANCE

In the East

During the final flowering of the Byzantine Empire, the “Palaeologan Renaissance” (1261–1453), the synthesis of Palestinian monastic and Constantinopolitan cathedral elements was finally achieved. A new style of music, the kalophonic, or “beautiful-sounding,” style emerged under the leadership of John Koukouzeles, who had been a monk on Mount Athos.30 Though still monophonic, the new style was much more florid and ornamental than the old and required a wider vocal range. Original compositions in this style by named composers are preserved in manuscripts called akolouthiai (orders of service) from the fourteenth century onward.

In the West

The Patronage System. In the West, beginning in the fourteenth century, the social context for music making began to change dramatically with the rise of the patronage system. While cathedrals and monasteries never ceased to celebrate musical liturgies, leadership in musical creativity passed to a new kind of institution: the private court chapel. Such a privately owned church formed part of the court household of a wealthy lay nobleman or of a high-ranking ecclesiastic, such as a cardinal or the pope. To enhance his reputation as a patron of the arts, the nobleman or ecclesiastic would hire musically trained clerics, the most expert he could find, to staff his private chapel and perform music at his court. Each musician would be paid by means of one or more benefices—that is, he would be appointed to a well-paying ecclesiastical post (bishop and abbot were especially desirable) and thus have the right to collect the income accruing to it, though in practice he would be exempt from actually having to reside or perform any duties at the church that was paying him. Though an obvious abuse, this practice did make possible the rise of the highly trained, specialized musical professional and the vast repertories of exquisite music that such musicians composed and performed. The extensive use of absentee benefices to support musicians may have been begun by the Avignon popes of the fourteenth century, and it only started to be curtailed by the Counterreformation popes of the sixteenth. As this source of income became scarce, musical patrons found other ways to pay musicians, who by the seventeenth century were more likely to be laymen than clerics. In this form, noble patronage continued into the nineteenth century. The last major composer whose entire career was supported by it was Franz Joseph Haydn (1732–1809). The gradual decline of the aristocracy and of noble patronage during the nineteenth century paralleled a shift toward music as a commodity, bought and sold widely in the form of concert tickets, sheet music, and, more recently, in the many forms of recorded and electronic media.

The Ars Nova. The music of the fourteenth century was described by its practitioners as a “new art” (Ars Nova), and earlier polyphonic compositions from the thirteenth century were relegated to the category of “old art” (Ars Antiqua).

Characteristics of the New Art included (1) isorhythm, or the practice of assigning a fixed sequence of rhythmic durations to the pitches of the tenor; (2) hocket (“hiccup”), in which two or more singers alternate notes and rests; and (3) notational advances that permitted each beat to be subdivided into two equal smaller notes as well as the traditional three, paving the way for the development of duple meters (e.g., our 2/4 and 6/8 meters) alongside the triple meters of modal and Franconian notation (our 3/4 and 9/8 meters). Although Pope John XXII, in a famous bull of 1322, forbade the use of most of these techniques in church music, his wishes were completely ignored. The fourteenth century saw the first written polyphonic settings of the ordinary of the mass and of the strophic hymns of the office, though these genres may have been performed earlier in improvised polyphony. Each portion of the ordinary is set in one of three styles: (1) resembling the contemporary isorhythmic motet, that is with an isorhythmic, often Gregorian tenor and faster-moving upper parts; (2) resembling the polyphonic secular French chanson, with the greatest musical interest in the highest-pitched melodic part; (3) in a simultaneous style, with all parts moving in the same rhythm. Simultaneous style may owe something to the older practice of improvising polyphony, about which we know so little. While some large collections of polyphonic mass movements survive from the period, we can also observe a tendency to assemble one movement of each type (i.e., one Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus, Ite) to form an entire polyphonic mass, even though the movements were created independently and even by different composers. Masses of this sort are preserved in manuscripts from Tournai,31 Toulouse, Barcelona, and the Sorbonne, the last of which, more progressive than the others, contains works that exhibit some musical relationships between the movements, for the Agnus incorporates material from the Kyrie and the Sanctus. What appears to be the first polyphonic setting of the complete mass by a single person is La Messe de Nostre Dame by the most important composer of fourteenth-century France, Guillaume de Machaut (d. 1377), a canon of Reims cathedral who held posts at several royal courts. Johannes Ciconia (d. 1411) wrote several pairs of Gloria and Credo movements, each pair being musically unified by stylistic similarities.

In the early fifteenth century musical leadership shifted to English composers, led by Leonel Power (d. 1445) and especially John Dunstaple (d. 1453). The new English style was admired on the continent for its avoidance of dissonances and its frequent use of the intervals of the third and the sixth. These English composers also developed the cantus firmus mass, the first fully unified settings of the entire mass ordinary, achieved by the technique of basing all of the movements on the same tenor melody, or cantus firmus, often a Gregorian chant or a secular song. From this time on, the five-movement ordinary (Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Agnus Dei) became the most important sacred musical form in the West. Several writers of the period regarded the new English style as a new beginning in music history, and for music historians today the period still marks the end of the Middle Ages and the beginning of the Renaissance.

The English innovations were soon adopted by the next generation of continental composers, led by the Burgundian Guillaume Dufay (d. 1474), who spent some years as a singer in the pope’s own private chapel before retiring as a canon at Cambrai. The leading composer of the next generation, Johannes Ockeghem (d. 1497), spent his career in the French royal chapel. His mass compositions include the earliest extant polyphonic Requiem, consisting of introit, Kyrie, gradual, tract, and offertory, and using the chant melodies as cantus firmi. A number of masses that lack cantus firmi display his outstanding technical expertise, being held together by elaborate contrapuntal techniques. The greatest composer of the Renaissance, Josquin Des Prez (d. 1521), belonged to a generation that included many talented and distinguished composers. Their use of imitative counterpoint and other techniques enabled them to treat all the polyphonic voices equally and gave them unprecedented control over their material. As Martin Luther remarked in his Table Talk, Josquin was a “master of the notes. They must do as he wills, whereas other masters are forced to do as the notes will.” Josquin inaugurated some important developments of the sixteenth century. His Missa Materpatris is a major early example of imitatio (later called “parody”) technique, in which the music is based on multiple voices of a polyphonic model rather than on a monophonic cantus firmus.32 In his motets he revealed a special interest in the expressive possibilities of an unusually broad range of affective texts, exploring an area that would increasingly occupy composers for the rest of the century. Josquin’s contemporary Heinrich Isaac (d. 1517) attempted to set to music the complete cycle of mass propers for the entire liturgical year. It was published after his death with the title Choralis Constantinus (1550–1555) after the city of Constance, Switzerland, though much of it was originally composed for the Hapsburg court chapel.

This new emphasis on the texts had a number of interrelated historical sources: humanistic interest in literature and poetry, the greater availability of books due to the invention and rise of printing, and the religious controversies over the Bible and other texts during the Reformation. The musical directives issued during and after the Council of Trent emphasized the intelligibility of texts and the elimination of secular elements as the two most important characteristics of sacred music. These directives led to a number of experiments by composers who sought to present the Latin text more understandably, by respecting the proper accentuation of the words and by minimizing highly florid passages and the simultaneous singing of different syllables in different parts. The most famous experiment of this kind, the Missa Papae Marcelli of the Roman composer Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina (1525–1594), became the object of a romantic legend that Palestrina had it performed at the Council of Trent itself, averting at the eleventh hour a determined attempt by the assembled bishops to ban all polyphony from the Catholic liturgy. Palestrina’s subsequent reputation during the seventeenth to early twentieth centuries wrenched him from his historical context and exaggerated his importance and influence by presenting him as the greatest of Renaissance composers (a distinction many today would confer on Josquin) and the model Counterreformation musician. But in fact his personal life was not especially exemplary, and his commitment to musical reform less palpable than that of lesser composers like Vincenzo Ruffo (c. 1508–1587) and Jacobus de Kerle (1531–1591), whose Preces speciales (1561–1562) actually were written for and performed at the council. It is best to see Palestrina as the culmination of one stream within Renaissance music, equal, but not superior, to such very different contemporaries as the prolific and cosmopolitan Orlando di Lasso (1532–1594) of the ducal court in Munich, and the multifaceted William Byrd (1543–1623), organist of the English Chapel Royal, who managed to remain a Catholic even though it was then illegal, and who composed music for both Catholic and Anglican services.

We still know less than we should about the late medieval and Renaissance liturgical practices that created the context for which so much polyphony was composed. We cannot merely assume that a mass or motet with a Gregorian chant tenor was composed to be sung at the date and time to which the chant was traditionally assigned. It is clear that it often was not, and the popularity of cantus firmi taken from secular songs seems to show that the selection of a cantus firmus was mainly a musical rather than a liturgical question, left to the composer’s choice rather than determined in advance by liturgical regulations. The so-called a capella ideal often attributed to Renaissance music is a nineteenth-century exaggeration. Except in the pope’s private chapel and perhaps a few other places, instruments were often used to accompany vocal polyphony in church.

THE LEGACY OF MEDIEVAL AND RENAISSANCE MUSIC TODAY

The concern for textual declamation and emotional expression ultimately brought Renaissance polyphony to an end, leading to the development of opera and the new Baroque style. For a long time, however, Renaissance music continued to be studied and performed in churches, for which it was thought more suitable. Baroque church music composed in Renaissance or pseudo-Renaissance style came to be known as stile antico (antique style), and counterpoint textbooks claiming to teach the style of Palestrina had an important place in music pedagogy down to our own century, the most important being the Gradus ad Parnassum of Johann Joseph Fux (1725).

The Eastern churches continued to cling to their monophonic chant, as most still do to this day. The first to make extensive use of polyphonic music was the Russian Orthodox church, influenced first by German Lutheran chorales and then by Italian operatic music. Some Russian composers of the eighteenth century actually studied in Italy or with visiting Italians such as Baldassare Galuppi (1706–1785), who directed the private chapel of Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg in 1765–1768. The monophonic Slavonic chant also continued to be sung, particularly among the Old Believers, with the old neumatic notation signs or znamenny, whence it has come to be called Znamenny chant.33 However, a modified staff notation (called Kievan notation) was also introduced under Western influence and is commonly used in the Russian Orthodox church. Polyphony has been sung in the Armenian Orthodox church since at least the nineteenth century. In the early nineteenth century, both the Armenian and the Greek Orthodox churches experienced a modernization of their medieval neumatic notation, with the result that the notation of the medieval sources ceased to be understood. Though modern scholars have made much progress in deciphering the Greek neumes, some problems of interpretation remain unsolved, and Armenian neumes are still not decipherable.

In the West, the nineteenth century saw the beginning of a great revival of both medieval chant (particularly by the Benedictines of the abbey of Solesmes) and Renaissance polyphony (the Cecilian movement). This “Early Music” revival continued into the twentieth century where it was greatly helped by the new availability of recordings. The ideals of the nineteenth century were enshrined in Pope Pius X’s motu proprio entitled Tra le sollecitudini of 1903, often described as the charter of the liturgical movement. In this document the pope taught that Gregorian chant was the supreme model of liturgical music, and that of other musics, Renaissance polyphony came the closest to it in spirit. As a result, for the first half of the twentieth century, the promotion of congregational singing of Gregorian chant was a major goal of the liturgical movement. After Vatican II, however, the disappearance of Latin and the new openness to the worldwide spectrum of folk and popular music led to a general abandonment of Gregorian chant and to a polarization between those church musicians who wished to preserve chant, polyphony, and classical music and those who thought it more important to promote popular music in the renewed liturgy. After a quarter-century standoff, however, it is time to move to a new synthesis. Chant and polyphony will not go away, indeed they are more popular among some of the general public than they have been for centuries. Just as the church, while it must be open to new theological insights from every quarter, can never abandon its biblical and historical Greek and Latin heritage, so the church, while it must penetrate and redeem every culture in the modern world, can never forget its historic musical heritage. The chant and the liturgy developed together as a single organic growth; the music, like the liturgical texts, is imbued with the spirit of the biblical and patristic traditions, an extraordinary treasury of profound musical wisdom. The tropes and polyphony that developed out of the chant partake of this spirit just as medieval commentaries and theological writings grew out of the biblical and patristic heritage. And just as theology today cannot ignore the historical development of doctrine from the early church to the present, so our musical life will not be healthy if it is expected to operate in a historical vacuum cut off from its past. The continued study and performance of this treasury of sacred music are therefore not optional but essential, and would have the beneficial side-effect of dramatically improving the standards of quality expected of all the other kinds of music performed in modern worship. The more serious one is about fully incarnating the gospel in the culture of the modern world, the more respect one will have for the liturgical song that is at the root of our own musical culture, the ancient and venerable ancestor of the many kinds of music we perform and enjoy today.

NOTES

1. G. Vermes, The Dead Sea Scrolls in English (New York, 1975), pp. 32, 81–82.

2. “Aristeas to Philocrates (Letter of Aristeas),” in Moses Hadas, ed. and trans., Jewish Apocryphal Literature, vol. 2 (New York, 1951), pp. 175–215.

3. Philo of Alexandria, The Contemplative Life, The Giants, and Selections, trans. David Winston, Classics of Western Spirituality (Mahwah, N.J., 1981).

4. James McKinnon, Music in Early Christian Literature (Cambridge, 1987), pp. 1–5.

5. Ibid., p. 98.

6. Ibid., pp. 27, 98–99.

7. Ibid., pp. 23–24.

8. Ibid., p. 25.

9. Ibid., p. 119.

10. Ibid., pp. 68–69.

11. John Wilkinson, Egeria ‘s Travels to the Holy Land, rev. ed. (Jerusalem, 1981), pp. 253–77.

12. For the history of one famous neuma, see Thomas F. Kelly, “Neuma Triplex,” Acta Musicologica 60 (1988): 1–30.

13. See Richard Crocker, The Early Medieval Sequence (Berkeley, 1977), p. 1.

14. See Ellen Reier, “The Introit Trope Repertory at Nevers: Mss Paris, BN lat. 9449 and Paris, BN lat. 1235” (Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Berkeley, 1981).

15. See Alejandro Planchart, The Repertory of Tropes at Winchester, 2 vols. (Princeton, 1977). Trope texts are now being published systematically in the volumes of the Corpus Troporum.

16. See Ruth Steiner, “The Prosulae of the MS Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, f. lat. 118,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 22 (1969): 367–93.

17. See Crocker, Early Medieval Sequence.

18. For bibliography, see David Hilley, “Ordinary of Mass Chants in English, North French, and Sicilian Manuscripts,” Journal of the Plainsong and Medieval Music Society 9 (1986–1987): 1–128.

19. For bibliography, see Ritva Jonsson, Historia: Etudes sur les genèse des offices versifiés (Stockholm, 1968); Andrew Hughes, “Modal Order and Disorder in the Rhymed Office,” Musica Disciplina 37 (1983): 29–51; and Andrew Hughes, “Research Report: Late Medieval Rhymed Offices,” Journal of the Plainsong and Medieval Music Society 8 (1985): 33–49.

20. See Andreas Holschneider, Die Organa von Winchester: Studien zum ältesten Repertoire polyphonischer Musik (Hildesheim, 1968); and Marion Gushee, “Romanesque Polyphony: A Study of the Fragmentary Sources” (Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1964).

21. Margot Fassler, “Accent, Meter, and Rhythm in Medieval Treatises De rithmis,” Journal of Musicology 5 (1987): 164–90.

22. Adalbert Kurzeja, Der älteste Liber Ordinarius der Trierer Domkirche: London Brit. Mus., Harley 2958, Anfang 14. Jh. (Münster, 1970).

23. See Guy Oury, “La structure des Vêpres Solennelles dans quelques anciennes liturgies françaises,” Etudes grégoriennes 13 (1972): 225–36.

24. Johannes Beleth, Summa de ecclesiasticis officiis, ed. H. Douteil, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Medievalis 41 (Turnhout, 1976), ch. 59, pp. 107–8.

25. Religious Latin Lyric poems in rhythmic style set to music; see Leo Treitler, “The Aquitainian Repertories of Sacred Monody in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries” (Ph.D. dissertation, Princeton University, 1967); and Thomas B. Payne, “Associa tecum in patria: A Newly Identified Organum Trope by Philip the Chancellor,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 39 (1986): 233–54.

26. See Anne Walters Robertson, “Benedicamus Domino: The Unwritten Tradition,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 41 (1988): 1–62.

27. See Wulf Arlt, Ein Festoffizium des Mittelalters aus Beauvais in seiner liturgischen und musikalischen Bedeutung, 2 vols. (Cologne, 1970); and Margot Fassler, “The Feast of Fools and the Danielis Ludus: Popular Traditions in a Medieval Cathedral Play,” in Thomas Forrest Kelley, ed., Chant in Context (Cambridge, forthcoming).

28. See Sarah Fuller, “The Myth of ‘St. Martial’ Polyphony,” Musica Disciplina 33 (1979): 5–26.

29. Michel Huglo, “Les débuts de la polyphonie à Paris: Les premiers organa parisiens,” Forum Musicologicum 3 (1982): 93–117.

30. First half of the fourteenth century; see Edward Williams, “John Koukouzeles’ Reform of Byzantine Chanting” (Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1968).

31. Jean Dumoulin et al., La Messe de Tournai (Louvain, 1988).

32. Howard Mayer Brown, “Emulation, Competition, and Homage: Imitation and Theories of Imitation in the Renaissance,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 35 (1982): 1–48.

33. See Joan Roccasalvo, “The Znamenny Chant,” Musical Quarterly 74 (1990): 217–41.

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

General

Duckles, Vincent, and Michael Keller, Music Reference and Research Materials: An Annotated Bibliography, 4th ed. (New York, 1988).

Fellerer, Karl Gustav, Geschichte der katholischen Kirchenmusik, 2 vols. (Kassel, 1972–1976).

Grout, Donald, and Claude Palisca, A History of Western Music (New York, 1988).

Hoppin, Richard H., Medieval Music and Anthology of Medieval Music (New York, 1978).

Hughes, Andrew, Medieval Music: The Sixth Liberal Art, rev. ed., Toronto Medieval Bibliographies 4 (Toronto, 1980).

The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. Stanley Sadie, 20 vols. (London, 1980).

New Oxford History of Music 2: The Early Middle Ages to 1300, rev. ed., ed. Richard Crocker and David Hiley (Oxford University Press, 1990).

Wilson, David Fenwick, Music of the Middle Ages: Style and Structure and Music of the Middle Ages: An Anthology for Performance and Study (New York, 1990).

Yudkin, Jeremy, Music in Medieval Europe (Englewood Cliffs, 1989).

The New Testament and Early Church

Bartlett, John, Jews in the Hellenistic World: Josephus, Aristeas, the Sibylline Oracles, Eupolemus (New York, 1985).

Ferguson, Everett, “Hymns,” “Music,” “Psalms,” Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, ed. E. Ferguson et al. (New York, 1990), pp. 441–43, 629–32, 763–65.

Jeffery, Peter, “Werner’s The Sacred Bridge, Volume 2: A Review Essay,” Jewish Quarterly Review (1987): 283–98.

McKinnon, James, Music in Early Christian Literature (Cambridge, 1987).

Philo of Alexandria, The Contemplative Life, The Giants, and Selections, trans. David Winston, Classics of Western Spirituality (New York, 1981).

Quasten, Johannes, Music and Worship in Pagan and Christian Antiquity, trans. Boniface Ramsey, OP (Washington, DC, 1983).

Smith, William, Musical Aspects of the New Testament (Amsterdam, 1962).

Vermes, G., The Dead Sea Scrolls in English, 2nd ed. (New York, 1975).

The Conversion of the Empire

Brock, Sebastian P., The Luminous Eye: The Spiritual World Vision of St. Ephrem (Rome, 1985).

Carpenter, Marjorie, trans., Kontakia of Romanos, Byzantine Melodist, 2 vols. (Columbia, MO, 1970–1973).

Jeffery, Peter, “The Introduction of Psalmody into the Roman Mass by Pope Celestine I (422–432): Reinterpreting a Passage in the Liber Pontificalis,” Archiv für Liturgiewissenschaft 26 (1984): 147–65. Re-Envisioning Past Musical Cultures: Ethnomusicology in the Study of Gregorian Chant (Chicago, 1992).

The Early Medieval Synthesis

Apel, Willi, Gregorian Chant (Bloomington, IN, 1958).

Cody, Aelred, “The Early History of the Octoechos in Syria,” East of Byzantium: Syria and Armenia in the Formative Period, ed. Nina Garsoïan et al., Dumbarton Oaks Symposium 1980 (Washington, DC, 1982): 89–113.

Conomos, Dmitri E., “Change in Early Christian and Byzantine Liturgical Chant,” Studies in Music from the University of Western Ontario 5 (1980): 49–63.

Dyer, Joseph, “Monastic Psalmody of the Middle Ages,” Revue Bénédictine 99 (1989): 41–74. “The Singing of Psalms in the Early Medieval Office,” Speculum 64 (1989): 535–78.

Fassler, Margot E., “The Office of the Cantor in Early Western Monastic Rules and Customaries: A Preliminary Investigation,” Early Music History 5 (1985): 29–51.

Gillespie, John, “Coptic Chant: A Survey of Past Research and a Projection for the Future,” The Future of Coptic Studies, ed. R. McL. Wilson, Coptic Studies 1 (Leiden, 1978): 227–45.

Hage, Louis, Le Chant de l’église maronite 1: Le chant syro-maronite, Bibliothèque de l’Université Saint Esprit 4. (Beirut, Lebanon, 1972).

Harrison, Frank LI., Music in Medieval Britain, 4th ed. (Buran, Netherlands, 1980).

Hiley, David, “Recent Research on the Origins of Western Chant,” Early Music 16 (1988): 203–13.

Mother Mary and Kallistos Ware, The Festal Menaion (London, 1969), The Lenten Triodion (London, 1978).

Nersessian, Vrej, ed. Essays on Armenian Music (London, 1978).

Shelemay, Kay Kaufman, and Peter Jeffery, Ethiopian Christian Chant: An Anthology, 2 vols., Recent Researches in Oral Traditions of Music 1. (Madison, WI, 1991).

Strunk, Oliver, Essays on Music in the Byzantine World (New York, 1977).

Szöfférvy, Josef, Die Annalen der lateinischen Hymnendichtung: Ein Handbuch, 2 vols. (Berlin, 1965). A Guide to Byzantine Hymnography, 2 vols. (Brookline, MA and Leyden, 1978–1979).

Wellesz, Egon, A History of Byzantine Music and Hymnography, 2nd ed. (Oxford, 1961; reprinted 1971).

Wilkinson, John, Egeria’s Travels to the Holy Land, rev. ed. (Jerusalem, 1981).

New Medieval Developments

Arlt, Wulf, Ein Festoffizium des Mittelalters aus Beauvais in seiner liturgischen und musikalischen Bedeutung, 2 vols. (Cologne, 1970).

Corpus Troporum 1– , ed. Ritva Jonsson [now Jacobsson], et al., Studia Latina Stockholmiensia 21– . (Stockholm, 1975– ).

Beleth, Johannes, Summa de ecclesiasticis officiis, ed. H. Douteil, Corpus Christianorum Continuatio Medievalis 41–41A (Turnhout, Belgium, 1976).

Crocker, Richard, The Early Medieval Sequence (Berkeley, 1977). “Matins Antiphons at St. Denis,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 39 (1986): 441–90.

Fassler, Margot, “Musical Exegesis in the Sequences of Adam and the Canons of St. Victor” (Ph.D. diss., Cornell University, 1983). “Who Was Adam of St. Victor? The Evidence of the Sequence Manuscripts,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 37 (1984): 233–69. “Accent, Meter, and Rhythm in Medieval Treatises ‘De rithmis,’” Journal of Musicology 5 (1987): 164–90. “The Feast of Fools and the Danielis Ludus: Popular Tradition in a Medieval Cathedral Play,” Plainsong in the Age of Polyphony, ed. Thomas Forrest Kelly (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 65–99. Gothic Song: Augustinian Ideals of Reform in the Twelfth Century and the Victorine Sequences (Cambridge, forthcoming).

Fuller, Sarah, “The Myth of ‘Saint Martial’ Polyphony.” Musica Disciplina 33 (1979): 5–26.

Gushee, Marion, “Romanesque Polyphony: A Study of the Fragmentary Sources” (Ph.D. diss., Yale University, 1964).

Hiley, David, “Ordinary of Mass Chants in English, North French and Sicilian Manuscripts,” Journal of the Plainsong and Medieval Music Society 9 (1986–1987): 1–128.

Holschneider, Andreas, Die Organa von Winchester: Studien zum ältesten Repertoire polyphonischer Musik (Hildesheim, 1968).

Hughes, Andrew, “Modal Order and Disorder in the Rhymed Office,” Musica Disciplina 37 (1983): 29–51. “Research Report: Late Medieval Rhymed Offices,” Journal of the Plainsong and Medieval Music Society 8 (1985): 33–49.

Huglo, Michel, “Les débuts de la polyphonie à Paris: Les premiers organa parisiens,” Forum Musicologicum 3 (1982): 93–117.

Kurzeja, Adalbert, Der älteste Liber Ordinarius der Trierer Domkirche: London Brit. Mus., Harley 2958, Anfang 14. Jh. (Münster, 1970).

Jonsson, Ritva, Historia: Etudes sur la genèse des offices versifiés (Stockholm, 1968).

Kelly, Thomas F., “Neuma Triplex,” Acta Musicologica 60 (1988): 1–30.

Marcusson, O., “Comment a-t-on chanté les prosules? Observations sur la technique des tropes de l’alleluia,” Revue de Musicologie 65 (1979): 119–59.

Oury, Guy, “Les Matines Solennelles aux grandes fêtes dans les anciennes églises françaises,” Etudes grégoriennes 12 (1971): 155–62. “La structure des Vêpres Solennelles dans quelques anciennes liturgies françaises,” Etudes grégoriennes 13 (1972): 225–36.

Payne, Thomas B., “Associa tecum in patria: A Newly Identified Organum Trope by Philip the Chancellor,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 39 (1986): 233–54.

Powers, Harold S., “Mode,” The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, ed. S. Sadie (London, 1980), 12: 376–450.

Planchart, Alejandro, The Repertory of Tropes at Winchester, 2 vols. (Princeton, 1977).

Reier, Ellen, “The Introit Trope Repertory at Nevers: Mss Paris, BN lat. 9449 and Paris BN 1t. 1235,” (Ph.D. diss., University of California at Berkeley, 1981).

Robertson, Anne Walters, “Benedicamus Domino: The Unwritten Tradition,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 41 (1988): 1–62.

Stäblein, Bruno, Schriftbild der einstimmigen Musik, Musikgeschichte in Bildern 3: Musik des Mittelalters und der Renaissance 4 (Leipzig, 1975).

Steiner, Ruth, “The Prosulae of the MS Paris, Bibliothèque Nationale, f. lat. 1118,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 22 (1969): 367–93. “The Music of a Cluny Office of Saint Benedict,” Monasticism and the Arts, ed. Timothy Verdon (Syracuse, 1984), pp. 81–113.

Treitler, Leo, The Aquitainian Repertories of Sacred Monody in the Eleventh and Twelfth Centuries (Ph.D. diss., Princeton University, 1967).

Waddell, Chrysogonus, OCSO, ed. The Twelfth-Century Cistercian Hymnal, 2 vols., Cistercian Liturgy Series 1–2 (Trappist, Kentucky, 1984).

Wright, Craig, Music and Ceremony at Notre Dame of Paris, 500–1550 (Cambridge, 1989).

The Late Middle Ages and Renaissance

Apel, Willi, The Notation of Polyphonic Music, 900–1600, 5th ed. (Cambridge, MA, 1961).

Brown, Howard Mayer, Music in the Renaissance (Englewood Cliffs, 1976). “Emulation, Competition, and Homage: Imitation and Theories of Imitation in the Renaissance,” Journal of the American Musicological Society 35 (1982): 1–48.