Psalm 136

For Choir, Congregation, Organ, and Optional Percussion

DON E. SALIERS

The rediscovery of psalms as sung prayer is one of the liturgical revolutions of our day. There is no doubt in my mind that this is an intrinsically ecumenical event as well, for it draws various Christian traditions back to a common source in Hebrew Scripture and permits us to share prayer forms more deeply than we have for centuries. For some time now I have found myself composing psalm settings each week for use by a specific Christian ecumenical community. Sunday liturgy at Cannon Chapel at Emory University, of Methodist origin, gathers a wide range of worshipers from different racial, ethnic, and denominational backgrounds. We have two choirs, one employing an African-American Gospel style, and the other a twelve-voice chamber choir that often presents anthems based on psalm texts. Thus the context for which this setting of Psalm 136 is conceived is itself a sign of considerable social and liturgical change.

Most of the time we use relatively simple forms of responsorial and antiphonal psalm singing, with an occasional metrical version drawn from the Genevan or Scottish traditions. I find myself also employing an improvisational cantillation of the texts. But there are several occasions that call for a more extended and more festive setting. So the opportunity to set Psalm 136 has provided a chance to move toward a “through-composed” form that incorporates a cantor (or a group in unison) with a small choir and organ (with optional percussion) to be in dialogue with the congregation’s refrain. In this psalm, of course, we have perfect litany form.

While not appearing often in the Common Lectionary, Psalm 136 speaks powerfully of God’s mighty acts and suits a number of festive occasions, particularly in the season from Easter to Pentecost. Interestingly enough, the psalm is appointed in a regular cycle: at evening prayer in the Book of Common Prayer for Saturday (vigil of Sunday morning), beginning with week 5 of Epiphany. Thus, the opportunity to use this kind of setting of a psalm in anthem style for choir and congregation occurs frequently. United Methodists, for whose recently published hymnal I wrote several antiphons, are now, as a denomination, in the process of learning to sing the psalms in public worship. This process itself has already begun to generate a new level of liturgical sharing across traditions and is generating new musical interests as well, particularly for the use of the choir to enable congregational song.

The translation of this psalm text struck me immediately as strong, even rough-hewn, with rhythmic complexity. I began my work by reading the text several times aloud until a basic treatment of the refrain began to emerge. Since we composers were urged to conceive our settings for actual liturgical celebration rather than for choral or solo recital, the refrain, “God’s covenant lasts forever,” would obviously anchor the assembly’s participation. In fact, structurally speaking, this psalm’s strongly litanic form is rare. But its very uniqueness left very open the relationship to be forged between singers, other musicians, and the congregation. The refrain had to be both clear enough for ease of entry in singing, and interesting enough not to become dull by repetition; accumulative force is the hallmark of litanies.

The text is not the vocative; rather, it is a declaration—a recital of God’s wonderful works. In my tradition the recently recovered eucharistic prayers, while addressed to God, contain this same pattern of active remembrance and declaration of God’s relations to creation throughout salvation history. The prayers invite petition and end in doxology. Psalm 136, then, has a very similar thematic structure: creation; redemptive history; universal providence; doxology. So I set about articulating the four-part thematic structure in musical terms. First, it occurred to me to have choral extensions or expansions at the four points of the form as in a concertato style. But my context called for something simpler. Thus the similar organ interludes, or comments, between the sections emerged, with an eight-measure carol-like section leading to the doxological ending.

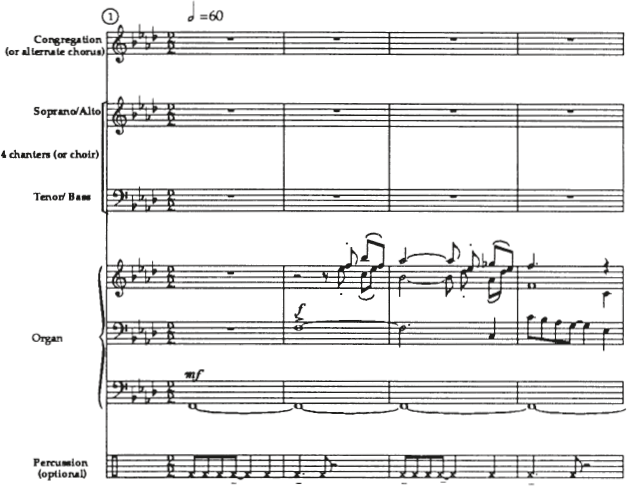

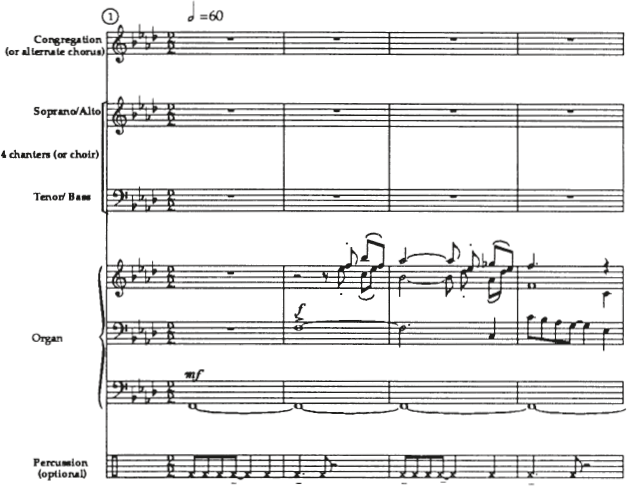

The four-part setting of the verses for four or eight chanters (or chamber choir) emerges in 6/8 meter in dialogue with the 2/2 of the refrain. In order to keep a tight unity and a secure relationship between choir and congregation, 2/2 becomes 6/8, with a half-note becoming a dotted quarter, maintaining throughout a steady, even relentless, pulse. The cantor’s role becomes one of mediator, as well as animator, between the congregation and the musicians. Additional percussion would strengthen the basic rhythm of the refrain and provide a richer texture over the organ pedal point F and the alternating F octave skips on the two principal beats of the measure. This reinforcement of the pulse is reminiscent of the rhythms found in some of Heinz Werner Zimmermann’s psalm settings.

When we think about the shift from passivity to the “full, active, and conscious participation” of the people, many of us are gravitating toward through-composed musical forms for liturgical use. This particular example gathers the whole assembly with its diverse gifts and roles into one complex, but mutually involving, act of praise. This new stress in worship, actively being present to one another, manifests both recent ecclesiological and theological shifts. Such shifts in self-awareness on the part of worshiping congregations assuredly reflects social change filtered through recent liturgical reforms. At the same time, distinctive Protestant forms of music, such as alternatum praxis among Lutherans, are being discovered ecumenically. For many Protestants, especially those of the broad middle “mainline,” worship still remains relatively static and even passive in its musical forms, save hymnody. Even with respect to hymns, the repertory remains relatively small. For most Protestants, until recently, choral, solo, and instrumental music were basically added on or inserted in as special music in worship. This situation is changing dramatically; at the heart of the change is the correlation of the recovery of psalm and canticle alongside the well-known “explosion” of hymnody in the past two decades.

One of the most profound aspects of social change in American culture is, quite obviously, the ecumenical mutuality and cross-pollenization that is now taking place. Borrowings of idiom and form across traditions occur in my setting of Psalm 136. One example is found in what emerged as I settled into F-minor (with A-flat major implied and other slight harmonic excursions). I kept hearing the opening bars of a tune called the Leoni Yigdal (Yigdal is the name of a morning hymn in the daily Jewish service. Set to music by an eighteenth-century British cantor, Myer Leoni, the work was overheard by Thomas Oliver, a Methodist minister, who thereupon borrowed it and altered the words for his own use). The tune is quite well known among most Protestant denominations, who use it for the text “The God of Abraham Praise,” or “Praise to the Living God.” In my setting of Psalm 136, references to the old Jewish melody appear in the pedal part of the organ interlude and open up in the last two verses by the chanters—the concluding verse being a fughette on the first line of the tune. Thus, when a Protestant congregation prays this psalm in song, the Jewish references become heightened, creating more depth and complexity in the activity of psalm-singing, as well as engendering a proper tension between the standard Christianization of psalm texts (via the older use of Gloria patri) and the original historical referents embedded in the psalm text itself.

A further reflection came to me in working with the strong center section: salvation, represented by the occupation of the land, requires displacement of others, and here another tension emerges. In history, God’s covenant has implications (not always happy ones!) for relationships between nations. The translators of this text have purposely omitted the slaying of kings—Og the king of Bashan, for example. At one point I considered returning these specific references and creating more turbulence underneath the praise of God who rescues us from our enemies. Yet this psalm finally holds the specific revelatory acts of God and the universal providence of God in dialogue. These become focused in the intensification of the word covenant as the psalm unfolds. So the refrain of the whole litany: “God’s covenant lasts forever.” By the end, this range of covenantal faithfulness has accumulated several meanings as well as musical textures. The universality of God’s particular choices and saving acts toward specific people shines through.

An afterword: My choir found the setting a bit difficult to learn and had some fear about its holding together in actual performance in the liturgy. Nevertheless, they did well; the congregation also held their own. All said: “This is a psalm translation that we won’t forget.”