Psalm 136

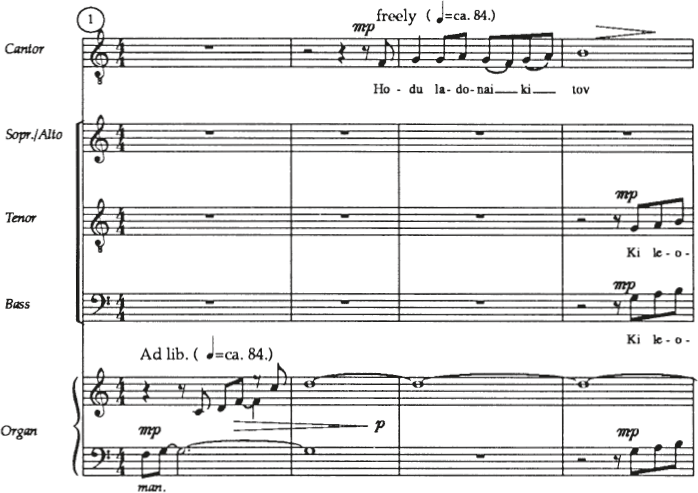

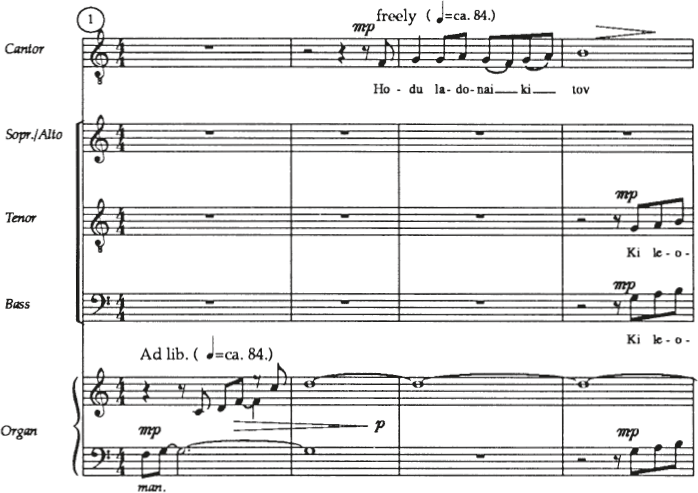

For Cantor, SATB Choir, and Organ

BEN STEINBERG

As a Jewish composer living and working in the late twentieth century, I am heir to an ancient musical tradition with a seemingly endless variety of modes, rhythms, melodic motifs, and structural ideas. At the same time, I am influenced by contemporary compositional techniques that admit a range of musical freedoms and sound-concepts unheard of during previous centuries. The fusion of these two possibilities—ancient Jewish and contemporary western—intrigues me: the combination of their musical languages offers me the unique opportunity to express my faith and sense of peoplehood through the artistic accents of my own time. The challenge for me is to write as a twentieth-century composer but with respect towards my forebears who bequeathed to me such a rich musical past. Thus, my Jewish compositions encompass simple gebraucht pieces, that is, necessary standbys that encourage congregational participation through easily singable, recurrent choruses; to pieces for cantor and choir that are designed for congregational listening; to more sophisticated, musically complex works for performance by chamber groups or chorus plus orchestra. While only a portion of my Jewish music is designed for use during religious services, all of it is to a certain extent liturgical, in the broad concept of the word liturgy as an expression of public worship. Indeed, I have often sensed a greater feeling of communal prayer during concert presentations of my cantata The Crown of Torah (for narrator, soloist, choir, children’s chorus, and instrumental ensemble) than in many more formal worship services. My own compositions reflect this experience and contain a variety of musical approaches.

No composer anywhere can be oblivious to social change, for life’s pace, its events, and its resultant resonances determine the sounds about us, the sounds of today, to which we all respond and which echo in our writings. Somehow, to study a work with a text written by a medieval poet or a biblical psalmist is to be confronted with the concepts of another time—a seeming contradiction in styles and an apparent confusion of incompatible mind-sets to which a composer must play matchmaker. Actually, they wed beautifully. The intelligent and careful introduction of contemporary musical techniques expands a good text, increases the effectiveness of its message, and illuminates its depths. This is no less true for composers today than in earlier centuries, when great composers like Palestrina, Bach, and Mozart set biblical or liturgical words to music.

Worshipers in synagogues or churches cannot disengage their twentieth-century ears as they enter a sanctuary for a worship service. The music they encounter in concert halls, or cannot escape in elevators, supermarkets, and television commercials, reflects their society’s sonorities, values, and technologies. What they hear also shapes their musical expectations and triggers involuntary responses to certain rhythms, harmonies, and tempi. The composer of commercial jingles knows this psychological dimension of music well and uses it effectively. The serious composer of religious music, no less aware, writes music that resonates accordingly. Artistic response to social change is not a choice—it is inevitable.

My setting of Psalm 136 offers an example. The people who commissioned the work requested that composers retain their documentation in order to “reconstruct the decision-making process” used during composition. Being a cooperative type, I did as I was told. I kept a few notes as I went along, and that was a mistake; trying to write music while looking over my own shoulder, as it were, became difficult for me. Still, I tried to follow the guidelines, which invited composers to write a usable and accessible choral piece that reflected not only some modern musical techniques but also Jewish tradition, perhaps through modes, nusach, chant, and so on.

As I looked at this text, therefore, what did I hear? An atonal setting for large chorus and symphony orchestra. But I finally stopped monitoring myself, quit taking notes, and pretended I was just writing something for a cantor, a good synagogue choir, and an organist. Then, later, I analyzed what I had written. Now I can say, as Bela Bartok once said when shown an analysis of one of his compositions, “I had no idea how clever I was.”

Four concerns became important to me in writing this piece:

First, the music should reflect the text closely, then be capable of assuming a wordless musical life of its own.

Second, the piece should be readily and quickly understood by a congregation. The form had to be recognizable, and if the piece was not actually easily singable for all, at least part of it had to be adaptable for congregational singing (I resisted the temptation to expand the music, and so, with the exception of a small bit of choral business in the third section, I kept it simple).

Third, both soloist and choir should have a characteristic role and express themselves with dignity.

Fourth, the traditional melodic theme customarily assigned to this text should be respected. This expectation, however, was problematic because of the confusion of nusach melodies for this text. In Jewish tradition, a nusach is a specific melodic pattern used by Ashkenazi, or northern and eastern European, cantors as a basis for improvisational chant. The particular nusach varies from service to service, from one holy day to another, and, indeed, from one community to another. Psalm 136 occurs liturgically as a Sabbath morning staple in a section of the service called pesukei dezimrah (the early morning rubric known as “verses of song”). The nusach for pesukei dezimrah is suggestive of a minor key for weekday mornings but is a kind of modified major for Sabbath mornings; this is further complicated by the fact that in the new Reform prayer book, this text is used not only in its original placement (mornings) but in the afternoon as well, where another nusach is the norm. I was thus confronted with three different models of nusach from which to choose. But Psalm 136 also turned up as part of the Passover seder liturgy, where yet another nusach governs liturgical chant, so the Passover model added to the possibilities. Not wishing to self-destruct like an overloaded computer, I elected therefore, to use a freer harmonic treatment. Perhaps my decision can be viewed as a composer adapting sacred sound to social change because of a desire for self-preservation. The traditional components I used were these: (1) a cantorial line in which musical accentuation is often achieved by melismatic embellishment; (2) an antiphonal approach, in part; (3) a modal treatment, in part; (4) the Hebrew language because, most importantly, I have always believed that both rhythm and melody are influenced by language.

For this setting of Psalm 1361 used the Hebrew version from the Gates of Prayer prayer book. The text divided itself neatly into four sections, an invocation followed by three sections dealing with the three subjects that would probably be considered mandatory religious reading for any Jew marooned on a desert island: Creation; Exodus as the paradigmatic act of God’s Redemption; and the final Redemption that we expect at the end of time. Specifically, the organization took this shape: invocation, verses 1–3; Creation, verses 5, 8, and 9; Exodus, verses 11, 12, 16, and 21; Redemption, verses 23–26.

A compositional problem was, of course, the recurrent refrain Ki le’olam chasdo (God’s mercy endures forever). The very phrase that gave the original text much of its strength, unity, and rhythm threatened musical redundancy, or even dullness. I decided to use the refrain in a number of ways. It appears in the first section (the invocation) traditionally, as an antiphonal response. In the second section (Creation) it was not used, because I was anxious for this part of the text to be presented in a flowing, uncluttered way. Then the refrain was clustered, chorally, as a bridge from the second to the third section (from Creation to Exodus). In the fourth section (Redemption), it was used antiphonally again, as in the first section. Initially, I had planned the total number of statements of “mercy enduring forever” to be the same as if the phrase had been retained as an antiphonal response (i.e., fourteen repetitions of Ki le’olam chasdo throughout the piece), but I decided that no one was capable of counting them anyway, so I changed my mind.

The musical decisions for this setting emerged from the text itself. The first section (the invocation) is a simple antiphony, musically quite symmetrical, except for a small extension in the last response. In the second section (Creation), I felt that the text should be clearly presented, especially the fifth verse, praising the God “who made the heavens with understanding.” Accordingly, the cantor sings this phrase, the choir joins in to explain the mechanics of creation (“the sun to rule by day, the moon and stars by night”), then the choir repeats the cantor’s initial phrase to emphasize that it was God “who made the heavens” and that they were “made with wisdom and understanding.” The third section (Exodus) begins with a choral bridge consisting only of the words Ki le’olam chasdo, since these words seem to provide the raison d’être for the reference to the Exodus. This leads to a cantorial solo (a traditional touch). Believing that we adorn the things we love and embellish the words we believe, the Ashkenazi cantorial tradition lingers lovingly over important phrases. In this tradition, improvisation plays a significant role. For this reason, these brief, free cantorial phrases are designed to sound improvisational, even to lend themselves to possible further improvisation. (Of course, as a synagogue composer I expect a cantor to recognize when this is possible and to perform the phrases with dignity.) The Exodus from Egypt is then described by the choir, with both rhythmic and harmonic movement, again punctuated by the use of the phrase Ki le’olam chasdo, especially surrounding the words (from Deuteronomy) that refer to God’s strong hand and outstretched arm. The part of the Exodus section that exhorts us to thank the God “who led the people through the wilderness” and “gave their land for a heritage” is to me so central to Judaic belief that it needs no shouting. The music, therefore, becomes subdued here, expresses gratitude rather than excitement, and functions as a few chord progressions to begin the modulation back to the original key.

Finally, in the last section (Redemption) is a universalist component in Judaism, beautifully expressed. Verse 23, quiet and respectful, refers to God’s remembering us at times of Egyptian bondage and Babylonian exile. Verse 24 describes deliverance, and just as the phrase resonates with hope and gratitude, so too the music rises. The phrase in both text and music that provides the climax in this section is the universalist statement in verse 25 that speaks of God’s giving sustenance to all people. This transition from God’s gift to the Jewish people to God’s gifts for all humankind seemed to me to represent the fulcrum of this section. From here, where does one go but to words of gratitude to the name of God as God was addressed by other nations—the God of Heaven? The final reference to God’s mercy enduring forever is not shouted with enthusiasm but spoken softly with respect.

Over many synagogue arks, which house the holy scrolls of Torah, there is printed the phrase Da lifnei mi atah omed (Know before Whom you stand). Traditionally, the cantor led the service, representing the people before God, while facing those words! That sense of reverence and even awe prompted the musical treatment of the piece’s final phrase. I attended a cantorial concert recently and to my surprise heard one soloist apologize to the audience for the fact that the piece he was about to sing had a quiet conclusion. He said he hoped he would get as much applause as his colleagues, whose pieces all had fortissimo endings. That questionable compositional approach notwithstanding, the last musical phrase in this piece quietly echoes the first, just as the final words themselves almost exactly duplicate the beginning of the psalm … and I hope no apology is necessary for the lack of a theatrical, fortissimo ending.