For Dr. Eric Werner with admiration and affection

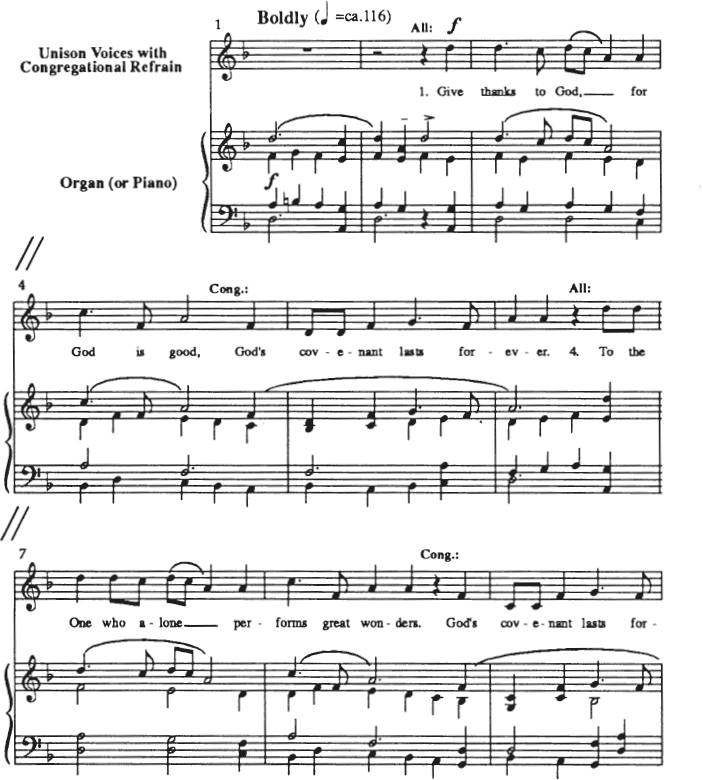

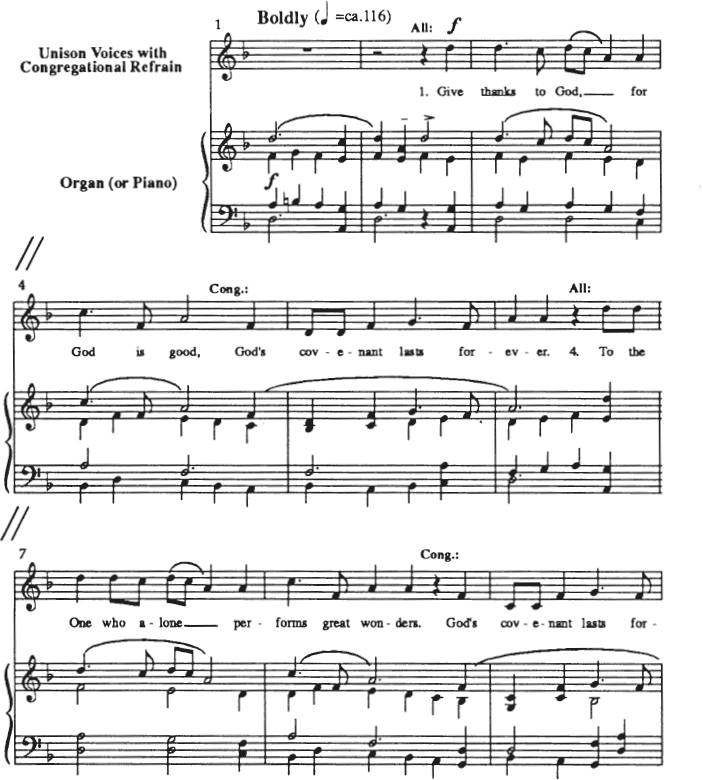

Psalm 136

For Unison Voices with Congregational Refrain and Organ or Piano

ALEC WYTON

A lifetime of work as a composer, performer, and director of music is an extraordinary gift. It offers a remarkable breadth of involvement from which to create and evaluate music for use in the church as well as to envision sacred music’s future possibilities.

My development as a church musician continues to this day. Membership in the Church of England offered early and lasting influences. As a young chorister I was exposed to the beauty of Anglican chants and hymns as well as other forms of English church music dating from the sixteenth to the early twentieth century. My first teacher trained me well in counterpoint and conventional harmony as well as in the discipline required for the performance of music on the piano and organ. Study at the Royal Academy of Music in London and at Oxford University brought exposure to the music of Vaughan Williams and Herbert Howells, with whom I enjoyed a lifelong friendship. My first job as an organist and choirmaster put me in contact with Benjamin Britten, C. S. Lewis, W. H. Auden, Henry Moore, and Graham Sutherland. I was in the midst of incredible creativity and artistic possibility. Especially Britten opened new doors that led to an expanded awareness of rhythmic, melodic, and harmonic variety.

Thus it is that my own compositions utilize a wide range of techniques: the harmonic freedom of modes, the resilience of counterpoint, and sometimes more conventional patterns. For the most part, texts suggest the appropriate choice for a musical setting. I read and reread the words until I hear music that will express their meaning. I follow the same process, whether I am composing a formal setting of the music for a eucharist, or an anthem, or a hymn, or an opera.

In my setting of Psalm 136, I used rhythmic patterns and key changes to provide a fresh access to the text. Triplets and duplets accommodate the irregular flow of the words. The repetitive motif throughout the psalm enables a congregation to be comfortable enough with the music to hear the text clearly. To this repetition, however, I added key changes in order to guard against monotony. The sudden change of key (verse 13) expresses what I consider to be an extraordinary moment in the text; I wanted people to sit up and take notice. I wrote this psalm with an ordinary congregation in mind, that is, a nonprofessional choir and a congregation of moderate musical ability that would enjoy the variety inherent in men’s and women’s voices.

Over the years of composing for the church, I have moved from emphasizing the choir as the most significant musical resource to developing a singing congregation. There’s nothing quite as transforming as a whole church singing together. I believe with Martin Luther that when people sing together they open themselves to the gospel in an unparalleled way. So every occasion of worship should offer a variety of musical expressions, some that are immediately accessible to all the people and some that the congregation must work at and grow with. This belief guides my composition. I write for a choir that will support the liturgical expression of the congregation, often in alternation with it.

My style of writing is influenced by a concern for word painting and the appropriateness of music for particular liturgical contexts. For example, in a composition for the celebration of Epiphany called “We Three Kings,” I wanted the music to convey the journey of these monarchs, so I wrote music that unmistakably conveyed such movement. But since a liturgical setting demands more, I thought carefully as well about the theological meaning inherent in this feast. The first goal was measurable: people will comment about whether the music expresses the journey of the Magi. But one can only hope that listeners will listen deeply enough to perceive the disclosure of God as well.

The season of Pentecost offers a different kind of challenge. Traditionally in the Episcopal eucharistic ritual, we sing a glorious plainsong sequence after the first reading assigned for the day. However, such sound seemed inappropriate as an answer to Acts 2:1–11, a text that describes the disciples’ response to the sudden presence of the Spirit among them. How could we presume such comfort, such security (inherent in the plainsong), after hearing a text that expressed surprise, fear, amazement, confusion? The liturgical context demanded music that matched the emotions of the reading. We moved the singing of the Pentecost sequence to another place in the service and substituted music that offered a similar expression to what had been felt by the disciples.

The breadth of musical tradition in the Episcopal church supports such choices. Neither the doctrine nor the practice of the church imposes restrictions on the use of any style, from the earliest chants to rock, pop, and jazz. A galaxy of sound makes room for a very inclusive community. If God created everything and everyone, then everything and everyone has the right and duty to praise God with the talents they were given. When I was organist and master of choristers at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York, we initiated an afternoon happening every Sunday in conjunction with evensong. We invited musicians and dancers from the Julliard School of Music to contribute what they were learning and imagining. The creativity they offered stretched us all and broadened our vision for Sunday mornings as well. Guiding our efforts to be open to new liturgical expressions was not so much a “worship free-for-all” where anybody who could strum three chords on a guitar or bang aimlessly on a drum was welcome to lead us. Rather, as the Rev. Walter Hussey, vicar of St. Matthew’s Church in Northhampton, said, “Only the best is good enough for God.” This belief remains with me even as I know that “the best” will vary from community to community.

Each community dictates its own possibilities. For example, from the sixties onward, influenced by the spirit of the times, people demanded simpler music that was accessible to everyone rather than appealing primarily to a musical elite. My own music at that time, especially in the late sixties and seventies, was rooted in a vivid tonality. Since then it has shifted to more conventional harmonies, all in an effort to make it possible for people to feel at home in church.

In addition to the influence of social demands on composition, practical considerations are also significant. My work at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine is an example. On any Sunday morning, 60 percent of the congregation was probably there for only a single time. To offer a genuine invitation for the people to participate fully was quite a challenge. What was required were familiar hymns and simple settings for the Creed, the Gloria, and the Lord’s Prayer with the choir’s four parts based upon a monotone that the congregation could sing without rehearsal.

Throughout my life I have been both intrigued and compelled by the power of music to create an ambience through which all people, no matter what degree of musical or theological sophistication they enjoy, would know something more about themselves and God. Music breaks barriers; music honors differences; music predicts possibility. Convinced that music has this power, I am committed to making it available to every congregation.