Note: This material has been summarized from R. J. Smith 1994, 18–26.

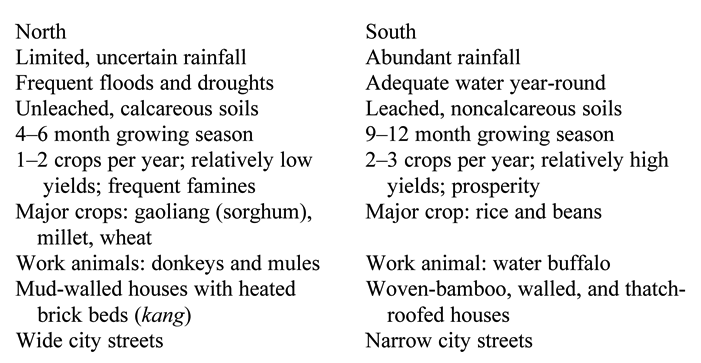

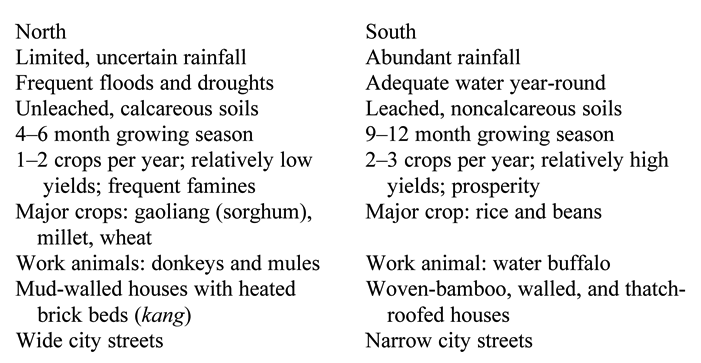

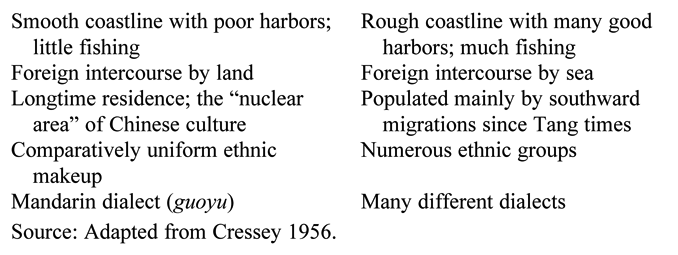

The boundary between north and south China is, of course, transitional; many geographical characteristics overlap or merge gradually from one area to the other. Nonetheless, striking and significant differences separate the regions north and south of the thirty-third parallel—a dividing line roughly marked by the Huai River in the east and the Qinling Mountains in the west.

Such differences help account, in turn, for other contrasts between north and south. The greater strength of the lineage or “clan” system in south China, for example, may be explained at least in part by the requirements of a productive, labor-intensive southern rice economy based on extensive, cooperative waterworks. Similarly, the greater political instability of the south can be attributed not only to the simple fact of distance from the political power center of Beijing, but also to the specific ethnic and other tensions arising out of the unique south China economic and social milieu. Talhelm et al. (2012) argue that “farming rice makes cultures more interdependent, whereas farming wheat makes cultures more independent;” thus, the authors conclude that “rice-growing southern China is more interdependent and holistic-thinking than the wheat-growing north.”

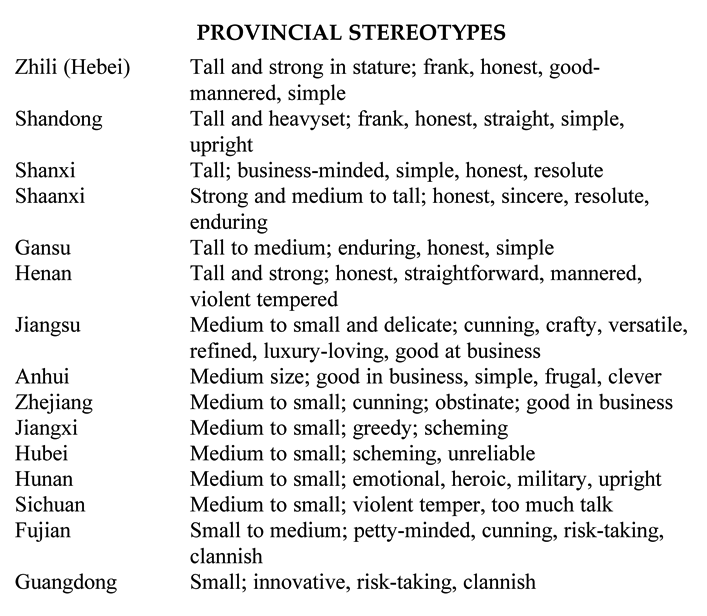

The regional differences and local identifications that often found their way into dynastic histories, local gazetteers, and private writings were derived from a wide variety of sources. Some reflected concrete geographical circumstances. The richly productive agricultural areas and well-developed commercial activities of south China, for example, encouraged the regional stereotype of southerners as greedy, shrewd, and sometimes unscrupulous. Northerners, by contrast, were viewed as upright and honest. Some regional stereotypes were based on historical and literary associations. Thus, the people of Hunan province were assumed to possess the sentimentality and emotionalism of their poetic countryman Qu Yuan (third century BC); the people of Sichuan, the love of music and adventure of their countryman Sima Xiangru (179–117 BC); and the people of Shandong, the frugality, simplicity, honesty, and sincerity of Confucius himself.

Still other stereotypes were based on cosmological principles. According to the pervasive Chinese theory of the five agents (see chapter 6), the element metal (jin) was associated with the direction west. People in west China were therefore believed to enjoy using weapons and to favor “cutting” (that is, spicy) food. Since the south was associated with fire (huo), southern Chinese were naturally supposed to be fiery in temperament. Northerners, by contrast, were like water (shui)—cold, stern, slow, and straight. The east belonged to the element wood (mu), giving easterners the characteristics of growing, flourishing, and constantly changing. The center corresponded to the element earth (tu), considered by the Chinese to be stable, well balanced, and harmonious. Thus the people of central China (variously defined) were solid and down to earth, without eccentricities.

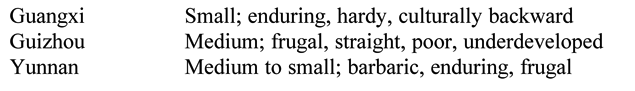

Multiple regional stereotypes were common, and occasionally they conflicted. But the striking feature of such stereotypes was their tenacity and widespread acceptance over time. Wolfram Eberhard’s 1965 study of contemporary Chinese provincial stereotypes on Taiwan, for instance, indicates a remarkable affinity with Qing dynasty views. According to this study the following major traits can be identified for each of the provinces of China Proper (excluding Xinjiang and Taiwan, which did not become provinces until the mid-1880s):

By way of comparison, we might consider the Kangxi emperor’s observations concerning the personality traits of his subjects:

Sometimes I have stated that the people of a certain province have certain bad characteristics: thus the men of Fujian are turbulent and love acts of daring . . . while the people of Shaanxi are tough and cruel. . . . Shandong men are stubborn in a bad way; they always have to be first, they nurse their hatreds, they seem to value life lightly, and a lot of them become robbers. . . . The people of Shaanxi are so stingy that they won’t even care for the aged in their own families; . . . and since the Jiangsu people are both prosperous and immoral—there’s no need to blow their feathers to look for faults. [At another point Kangxi remarked] “The people of the North are strong; they must not copy the fancy diets of the Southerners, who are physically frail, live in a different environment, and have different stomachs and bowels.”

County gazetteers (xianzhi) promoted more localized stereotypes. In general, the elite compilers of these works distinguished between residents who were comparatively docile and those who were potentially troublesome. Those in the former category (the vast majority of China’s counties) tended to be described by stock phrases indicating the “absence of feuds,” the avoidance of “involvement in lawsuits,” and the habit of “never evading tax payments.” Those in the latter category were labeled as “hot tempered,” “frequently involved in feuds and lawsuits,” and “militant.” Such designations did not necessarily apply throughout any given province, however. In Hubei, for example, the residents of Huang’an county came to be described as “tough and daring,” whereas in nearby Huanmei the local people were viewed as “soft and timid.” Similarly, in Hebei the natives of Xuanhua appeared in county gazetteers to be “militant and adventurous,” while in Shunde they were “mild, inactive, and fond of learning the Confucian Classics.”

The prevalence of such regional, provincial, and local stereotypes unquestionably affected the outlook and policies of both the throne and local Qing officials, who were prohibited by law from serving in their home areas. They also affected the conduct of Chinese personal and commercial relations—including what G. William Skinner 1971 refers to as the “export” of entrepreneurial talent. Certainly it is no accident that fellow provincials from three neighboring counties in central Shanxi dominated the remittance banking business in China for over a century. Regional and local stereotypes may even have influenced the subconscious self-image of individuals in China. Obviously, they posed an obstacle to nationwide social and political integration.